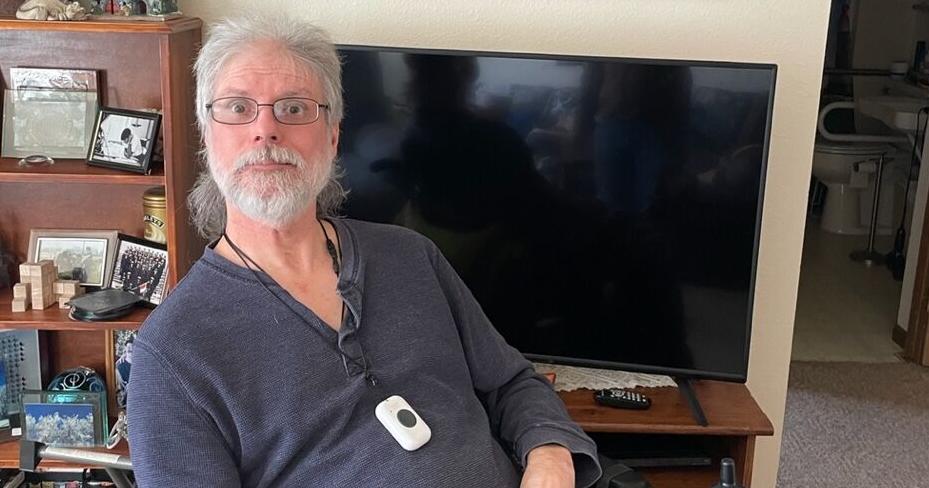

Joe Yasenchack suffered a brain aneurysm in his early 30s. The sudden trauma put him in a coma for three and a half months, followed by 18 years of nursing home care.

The Cleveland, Ohio, native who is now a resident of Harvey has lived independently for the past three years, as much as someone in his condition can.

A power wheelchair is his means of mobility, inside his two-bedroom apartment, and out on the streets of this town of about 1,600 people. He makes a meager income from occasional sales of his artwork and graphic design gigs, skills he picked up during his 14 years with the U.S. Coast Guard.

At the moment he faces a new crisis. Very soon he must move out of his home at Harvey Manor Apartments.

This federal Housing and Urban Development housing project near the local high school is being sold to new ownership who will redevelop the property. Most other tenants have already departed.

People are also reading…

Yasenchack has few other options in town needed to accommodate him.

“The problem is that apartments around here have five steps to go down and five steps to go up,” Yasenchack said. “Not very accessible.”

Yasenchack’s plight highlights the difficulties facing renters in North Dakota with disabilities and mobility issues and the lack of availability of accessible units.

His rental costs also rose by 18% in December, from $420 to $496, a situation which mirrors rising costs for a multitude of renters across the state.

For Yasenchack, other apartments nearby are too small — either a studio or a one-bedroom — providing insufficient space needed for work and comfort, he said. They’re also more expensive.

A housing needs assessment released in late 2022 by the Center for Social Research and North Dakota Housing Finance Agency found rental costs increased 49% between 2010 and the end of 2020, hitting lower-income North Dakotans the hardest.

According to the research, median rental prices were at $828 by the end of 2020.

More recent data from RentHub shows average median rent across the state increased nearly 11% between April 2020 and April 2023 – rising from $835 to $923.

Surge in assistance

As of May 1, ND Rent Help, a pandemic-era program distributing federal funding to households struggling with rental and utility payments, stopped accepting new applications.

The end of the program raises the specter of increased rent-related stress for lower-income families.

ND Rent Help saw a surge of payouts early this year, signaling both an increase in efficiency of distributing the aid, but also the increased need for assistance.

A total of $9.4 million was distributed in February, and $9.7 in March, the latter the highest monthly payout since the program started in January 2021.

Those same months in 2022 were considerably less — $5.5 million and $8.2 million.

Andrea Olson, executive director of nonprofit poverty agency Community Action Partnership of North Dakota, said the surge in need shown in the ND Rent Help data is reflective of what her organization has seen in the past several months.

“The calls for rental assistance have not slowed down,” Olson said. “They have increased and there just appears to be no end in sight.”

ND Rent Help has provided housing stability to over 17,500 lower-income households as well as assistance to 2,700 households experiencing homelessness to get into rental units.

The $40 million left in the program will go toward households with more “urgent and critical” potential of experiencing homelessness, said Department of Human Services Executive Director Jessica Thomasson.

With ND Rent Help expiring, that leaves NDHFA as the sole state agency administering low interest loans, tax credits and rental assistance programs.

Currently there are over 12,600 subsidized multifamily housing units in the state, with only 4,300 of those getting rental assistance, according to the NDHFA needs assessment.

That report also shows more than 62,000 residents in the state paying over 30% of their income toward rent – considered out of the range of affordability.

At a crisis point

Sister Kathleen Atkinson, director of social services organization Ministry on the Margins, which assists those facing hunger and homelessness in the Bismarck area, describes the rental and housing situation as a “huge crisis” both in aspects of affordability and accessibility.

“Affordable housing is housing that you can maintain with your job,” Atkinson said.

“For people on the lower income spectrum, trying to get into rental housing, they’ve often got to have a couple thousand dollars up front in accessible money,” she said. “If you’re working minimum wage, to have your down payment, your first month’s rent, and pay for background checks is expensive.”

Atkinson said she’s increasingly seeing people who have been hit by some significant crisis that knocks them out of a moderate-income range.

This could be a job loss, a health care or mental health crisis, addiction or incarceration. When those crises hit the primary earner, it can leave a whole family untethered and unable to pay mounting costs.

“Whatever the crisis is, if you’re living that close to the edge, and you miss a couple payments and then you just kind of spiral,” she said. “And it can all happen in a couple of months.”

Action to address costs, supply needed

Thomasson said her office is digging through data going back to May 2020 to get a better idea of how much rental prices have increased since the pandemic and hopes to have concrete answers by mid-summer.

That study could inform a legislative study passed under House Concurrent Resolution 3030 in March, which will examine homelessness and barriers to housing in the state.

“What we’re hearing from people is that they’re just having trouble making ends meet even if they are working,” Thomasson said. “Anecdotally we’ve certainly seen increasing rents just as we’ve all seen increases in food, gas and other costs.”

Because of the increased cost of homeownership, particularly for first-time home buyers, more potential homeowners are being pushed into the rental market.

This shift is driving up rental prices and impacting the supply of rental housing, said Andrew Aurand, Washington D.C.-based senior vice president of research for the National Low Income Housing Coalition.

“It’s really putting pressure on the rental market and it’s creating even bigger affordability problems for lower-income renters,” Aurand said. “We’re seeing that trend in many markets and nationally that’s the trend.”

Rental price surges started in 2021 just as most people were starting to go back to normal work routines following the pandemic, he said.

“If you’re a low wage worker, or extremely low-income renter, you were probably struggling even before the rapid inflation increases (last year),” Aurand said. “They’re struggling even more now.”

Limited rental supply is also reflected in the data, with the most recent figures showing an acceptable overall 8% vacancy rate in the state.

This, however, can fluctuate with higher supplies in some areas and almost none in others. For example, 2020 data showed only a 1% vacancy rate in Eddy County, but a 28% rate in Mercer County.

Data from late 2022 showed that only 3.1% of apartment units in Fargo were vacant, down from around 9% in 2020.

“It’s hard to build stuff that is affordable to lower income households just from a pure market perspective,” Thomasson said. “One of the things we’ve learned is just the breadth and scope of this issue. It really is every county, every community, households just across the spectrum are facing the challenge.”

The North Dakota News Cooperative is a nonprofit providing in-depth journalism. For more information, including how to donate, visit www.newscoopnd.org.