Finance

InDrive Eyes Financial Services To Bolster Presence In Developing Markets

InDrive president Mark Loughran

Ride-hailing company inDrive is exploring financial services products in the developing markets where it is active.

Mark Loughran, the company’s president and deputy CEO, who joined the company last summer, said that the move would enable greater financial stability for drivers on the platform.

InDrive was founded in Russia and is now headquartered in the U.S. Much of its business is in developing markets in Asia, Africa and Latin America but last year ventured into the U.S. market with a launch in Miami.

Loughran joined inDrive to grow these various parts of the business as well as develop new ones, including a $100 million program to support businesses in developing regions.

The move into financial services would be targeted at drivers in markets where there may be financial instability and strain.

“[It’s] for those drivers in the developing markets, when something happens in their family or maybe something happens to their vehicle or their bike or whatever and they need to fix it. We’ve been starting to look at financial services and options there, just piloting some ideas.”

The plans are at an early stage, Loughran said, but the company is looking at potential partnerships in these markets with services like lending in mind for drivers and delivery riders that need financing for cars or bikes.

“On the financial services side, it’s more helping with thinking about access to financial services, like small term loans. You’re talking about people who would have previously no banking credibility at all,” Loughran said.

“They wouldn’t be able to do that, where they’d have to go for a loan is not a good option for them or their families. So [we’re] looking at different ways that we could support them, we’re testing it on a very small scale.”

The model of providing financial services, namely loans, to delivery and ride-hailing companies is not a new one with fintech start-ups popping up in recent years to address that market. This includes Moove, which is active in Africa.

“It’s back to our commitment to make sure that those increasing numbers of drivers can be supported, their earnings can be stable and also it can work for them financially, which is why we take the low percentage take rate versus our competitors,” Loughran said.

Late last year, inDrive launched a $100 million program to invest in businesses in emerging markets in a bid to further its presence there and support smaller enterprises. While inDrive has focused heavily on ride-hailing and deliveries in these developing regions, it launched in the U.S. last year with tentative steps into Miami.

InDrive differentiates itself from competitors like Uber and Lyft with its bidding model where passengers can negotiate a fee for their journey rather than a set price. InDrive takes up to 10% in commission, depending on the market.

Loughran said the U.S. expansion remains nascent with no immediate plans to move into other cities. Rather, the company is refining the Miami business and gathering data on its performance.

“It’s been probably four months or something [since the Miami launch]. It’s some period of time but not an enormous period of time. I think we just need to continue with that model and obviously look at is it sustainable? Will it continue to grow into next year with the same enthusiasm as it started? How does the profitability look?” he said.

“The cost of doing business in the U.S. is very different from some of the other markets. This is our chance to learn that and make sure we get the whole offering correct.”

The company would not disclose any driver or passenger numbers in Miami.

Loughran is a former executive at Microsoft and Honeywell and joined inDrive in July 2023 while the company raised $150 million in funding almost a year ago to expand the business’s geographic footprint and its other verticals like delivery.

InDrive does not disclose any revenue figures but Loughran said that the company is “on a good track” to profitability.

“Now it’s about us making sure that we get to the right level of scale to make sure that the investment that we’ve got in our central tech stacks and everything else can then be absorbed by the number of the rides. We’ve got a very strong focus on that, we’re certainly on a path to that, so I would be positive about our path to that.”

Finance

Non-bank financial intermediation: Research, policy, and data challenges

Non-bank financial intermediation (NBFI) has been in the news. This form of financial intermediation has grown fast since the global financial crisis (GFC), and its size now equals that of banks in many countries (Acharya et al. 2024 ). Presumably, this growth reflects the demand for, and economic benefits of, the specific services offered by non-bank financial intermediaries (NBFIs). Yet, NBFI has also been in the news as a factor behind some recent financial stresses (e.g. FSB 2020). These events, including severe dysfunctioning in core bond markets, have necessitated large central bank interventions. Related, some have questioned the spare wheel role of NBFI, the notion that it will help with financing the real sector in times of stress. Rather, some recent analysis (e.g. Forbes et al. 2023, Aldasoro et al. 2024) suggests that NBFI is less willing than banks to tie borrowers over during crises and may actually be more procyclical.

Reflecting this, in a recent paper (Claessens 2024) I review research and policy work on NBFI from a financial stability perspective. Reflecting its growth, stability, and procyclicality issues, NBFI has been researched more recently (for another review, see Aramonte et al. 2023) and received much more policy attention (e.g. FSB 2024). In some sense, this reflects a catching up with the attention long given to banking. But there are many differences. For one, NBFI is more diverse than banking, including as it does money market and other asset management vehicles, pension funds and insurance corporations, making for many aspects to cover and issues to consider. I therefore focus on market-based forms, and within that subset, on debt-related intermediation, as that is most closely associated with financial instability. And, as NBFI emerged more recently, it has led to crises only lately. Since NBFI-related financial instability is very episodic, there are few such events – less so than related to banking. Together, this has made it harder to study its financial stability properties than for banking.

With these caveats in mind, I first document the rapid growth of NBFI. While it has slowed down recently, since the GFC its growth has exceeded that of other financial assets (Figure 1a; for more details, see FSB 2023b). NBFI assets now account for nearly one-half of total global financial assets (Figure 1b). In 2022, approximately 65% was held by so-called other financial intermediaries (OFIs) – institutions other than central banks, banks, public financial institutions, insurance corporations, pension funds, or financial auxiliaries. Among OFIs, about three-quarters are collective investment vehicles (CIVs), such as money market funds (MMFs), fixed-income funds, balanced funds, hedge funds, and real estate investment trusts. Relative to GDP, between 2012 and 2022 they grew by 7 percentage points in the UK, 3 percentage points in Italy, 2 percentage points in Japan, 1 percentage point in the US, roughly doubled in Brazil and South Africa, and increased by one-third in India. While attribution is difficult, the low interest rate environment, generally low asset price volatility, as well as technological advances and financial reforms likely drove this growth.

Figure 1 Total global financial assets and the NBFI share

Notes: The NBFI sector includes all financial institutions that are not central banks, banks, or public financial institutions. Included are all Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, the Cayman Islands, Chile, China, the euro area, Hong Kong SAR, India, Indonesia, Japan, South Korea, Mexico, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, South Africa, Switzerland, Türkiye, the UK, and the US. Panel a includes data for Russia up until 2020; panel b does not include data for Russia.

Source: FSB (2023b).

Stress periods related to NBFI are rare and can be triggered by many shocks, but they appear to have increased in frequency. The onset of the GFC, the global COVID-19 outbreak in March 2020, and, most recently, the start of the war in Ukraine have been associated with NBFI-induced financial stress. Most were due to CIVs, which have features that make them susceptible to runs and have driven the NBFI growth since the GFC. But it can be other NBFIs too, as in the UK in September 2022 when gilt interest rates rose following a mini budget announcement, triggering a crisis among pension funds as collateral calls related to so-called liability-driven investments could not be met.

Research has documented the benefits of NBFI in terms of greater access to finance and economic impact, relating these to its specific comparative advantages in maturity and liquidity transformation; its specialisation (for example, some CIVs invest (mostly) in one specific asset class) and ability to finance riskier but more productive segments; its greater allocational efficiency relative to banks (due to its more decentralised nature), at least for some types of investments; and its risk-pooling and diversification benefits for final investors. NBFI’s complementary relationships with banks and capital markets, which can be from the supply and demand side, are also argued to provide benefits.

The risk-reduction benefits of NBFI arise in large part from the diverse forms of financial services it provides. NBFI generally uses instruments that involve greater risk-sharing among a wider pool, which can benefit borrowers. Also, since NBFIs do not have very highly levered balance sheets and are not core to the payment system as banks are, individual NBFI failures tend to have less systemic consequences. Evidence also supports that better-developed capital markets, typically associated with more NBFI, mitigate the negative real effects of crises. But NBFI comes with its own risks, related specifically to interconnections and interactions between liquidity and leverage, and can be procyclical too.

The connections between NBFIs and banks, often referred to as shadow banking, have been extensively analysed post-GFC, as they contributed to that crisis. These links are much smaller today due to various reforms. Still, they and related risks remain (e.g. Acharya et al. 2024), as the large impact of the bankruptcies of Archegos Capital Management and Greensill Capital on some banks showed.

The main systemic risk analysed in relation to NBFI recently has been its fragile liquidity. The underlying mechanisms are well-known (Aramonte et al. 2023) and were present in several recent stress events. At its core are the interactions between liquidity mismatches and leverage with risk-management practices, with the latter influenced in part by regulation. Fragile liquidity can arise from those NBFIs that issue liabilities with near-money characteristics yet are backed by illiquid assets and channelled through vehicles with no (or limited) ability to generate their own liquidity. These forms include MMFs and other types of CIVs. When faced with large-scale redemptions and other withdrawals, such CIVs can quickly run down their buffers. Additionally, in times of stress, fund managers typically hoard cash. Both behaviours can make CIVs want to sell assets at times of few buyers. The demand for liquidity services from dealers may rise, but their supply is not elastic either. Market imbalances may follow. Depending on the size and concentration of investments CIVs hold, this can lead to fire sales and potential market dysfunctions, with spillovers to other parts of the financial system and the real economy.

Such collectively destabilising behaviour and dynamics were analysed well before recent events. New theoretical and empirical work has clarified old and identified new channels, highlighting the large role of leverage in general, and more recently the role of NBFI. Several papers show how stresses in the US Treasury market in March 2020, at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, in the form of the dash for cash related to NBFI actions (e.g. Schrimpf et al. 2020, FSB 2020). Open-ended funds investing in corporate bonds amplified the bond market stresses in March 2020 as they liquidated assets on an elevated scale (e.g. Claessens and Lewrick 2021). And large margin calls led to price spillovers and stresses in commodity markets in March 2022 when energy and other prices spiked following the invasion of Ukraine (e.g. Avalos and Huang 2022). Finally, the procyclicality of NBFI shows up in the reduced access to external financing domestically, but also in cross-border financing, during stress periods (e.g. Fleckenstein et al. 2020, Chari 2023).

Especially following bouts of stress leading to large-scale central bank interventions, policy work has increasingly focused on NBFI. Areas addressed or covered in policy proposals include MMF resilience; liquidity management in OEF; margining practices; the liquidity, structure, and resilience of core bond markets; and US dollar funding and related external vulnerabilities for emerging market economies. Additionally, the role of central banks in responding to market dysfunction has been analysed. Progress with these reforms and policy proposals is summarised in FSB (2023a). While policymakers have been active, the paper points out the many outstanding issues and suggests further analytical work.

One last challenge is data. While many parts of the NBFI sector, at least as covered here, are very transparent, in many ways more so than banks, there are large data gaps which hurt market discipline and supervisory effectiveness. At the same time, analysis of the UK September 2022 event (Pinter 2023) showed that by matching various price and quantity data, it could have been anticipated. Nevertheless, steps can be taken to enhance the disclosure and availability of data and address remaining data gaps.

References

Acharya, V, N Cetorelli and B Tuckman (2024), “Transformation of activities and risks between bank and non-bank financial intermediaries”, VoxEU.org, 29 April.

Aldasoro, I, S Doerr and H Zhou (2024), “Non-bank lending during crises”, CEPR Discussion Paper 18989.

Avalos, F and W Huang (2022), “Commodity markets: shocks and spillovers”, Bank for International Settlements Quarterly Review, September: 15–29.

Aramonte, S, A Schrimpf and H S Shin (2023), “Non-bank financial intermediaries and financial stability”, in R S Gürkaynak and J H Wright (eds), Research Handbook of Financial Markets, Edward Elgar Publishing.

Chari, A (2023), “Global risk, non-bank financial intermediation, and emerging market vulnerabilities”, Annual Review of Economics 15: 549–72.

Claessens, S (2024), “Non-Bank Financial Intermediation: Stock Take of Research, Policy and Data”, CEPR Discussion Paper No. 18945.

Claessens, S and U Lewrick (2021), “Open-ended bond funds: systemic risks and policy implications”, Bank for International Settlements Quarterly Review, December: 37–51.

Fleckenstein, Q, M Gopal, G Gutierrez and S Hillenbrand (2020), “Nonbank lending and credit cyclicality”, Harvard Business School Working Paper.

FSB – Financial Stability Board (2020), Holistic review of the March market turmoil.

FSB (2023a), Enhancing the resilience of non-bank financial intermediation, Progress Report.

FSB (2023b), Global monitoring report on non-bank financial intermediation 2023.

FSB (2024), FSB Work Programme for 2024.

Forbes, K, C Friedrich and D Reinhardt (2023), “Funding structures and resilience to shocks after a decade of regulatory reform”, VoxEU.org, 29 June.

Pinter, G (2023), “An anatomy of the 2022 gilt market crisis”, Bank of England Staff Working Paper 1019.

Schrimpf, A, H S Shin and V Sushko (2020), “Leverage and margin spirals in fixed income markets during the Covid-19 crisis”, Bank for International Settlements Bulletin 2. https://www.bis.org/publ/bisbull02.pdf

Finance

Financial Wellness Center aims to customize student support – @theU

The Financial Wellness Center— specialized in enhancing students’ understanding of the role of finance in their lives and assisting them in making smart, informed decisions about their money—aims to improve the way it supports students by providing the right information at the right time to the right students.

“Each student’s financial wellness journey is unique, shaped by their distinct needs, circumstances, goals, and aspirations,” explained Gabrielle Mcallaster, director of the Financial Wellness Center. “It is clear that a one-size-fits-all approach to financial counseling does not suffice, and our students require distinctive guidance and support tailored to their individual situations.”

To accomplish this and to prepare for an increasing student population, the center is evaluating its processes and exploring how technology can support staff in providing students with an experience tailored to their needs and interests.

The center is partnering with University Information Technology to pilot the use of Salesforce as a customer relationship management platform. The way the system is being configured, each student’s personalized journey will begin with their profile, which includes demographic information, eliminating the need to ask redundant questions during each visit. Student profiles also serve as a repository for staff to add case notes from one-on-one counseling sessions and view notes from previous sessions, ensuring a comprehensive understanding of each student’s progress over time at the university.

Additionally, staff can indicate students’ interests on their profile, such as investing, saving, or budgeting. The technology then uses this information to invite students to workshops related to their interests, enhancing engagement and support.

Moreover, with the platform, the center can send automated communications to students. For example, if a student misses their counseling session, they will receive an email asking them to reschedule. This feature enhances the center’s ability to maintain consistent communication with students and helps students stay informed and engaged.

While this initial effort is focused on updating the Financial Wellness Center’s case management processes and implementing customized and automated follow-up communications to help students work toward their financial goals, it also presents an opportunity to prepare for future expansion into other Student Affairs departments. Collaborating with various departments within UIT, Student Affairs will use this test case to learn and plan for how to create the most seamless experience for students.

“As we look to incorporate this into more departments, we envision curating a host of information, resources, invitations, follow-ups, and connections from a wide range of offices,” said Annalisa Purser, special assistant for strategic initiatives in Student Affairs. “We want to be proactive in providing students with personalized information and experiences to support their individual student journeys.”

Finance

Waaree Energies partners Ecofy for low-cost finance to rooftop solar customers

Waaree Energies Ltd, India’s largest solar PV module manufacturer, has partnered with Ecofy, a non-banking finance company backed by Eversource Capital, to provide low-cost, hassle-free finance to homeowners and MSMEs adopting rooftop solar systems.

Waaree Energies Ltd, India’s largest solar PV module manufacturer, has collaborated with Ecofy, a non-banking finance company backed by Eversource Capital, to provide low-cost, hassle-free finance to homeowners and MSMEs adopting rooftop solar systems. Ecofy has committed INR 100 crore into the partnership.

The partnership will leverage Waaree Energies’ solar expertise and Ecofy’s digital financing solutions to accelerate the solarisation of over 10,000 rooftops across households and MSMEs, contributing to the government’s target under PM Surya Ghar Yojana 2024.

Kailash Rathi, head of partnerships and co-lending at Ecofy, said, ” Over the past 15 months, Ecofy has empowered over 5000 rooftop solar customers. We have invested heavily in this segment enabling penetration through product innovation and instant approvals. As the country prepares for the peak solar season, the collaboration between Ecofy and Waaree is expected to act as a catalyst, and aid in accelerating solar adoption and penetration across diverse segments of society.”

Pankaj Vassal, president-sales at Waaree Energies, said, “By integrating our solar solutions with Ecofy’s financing platform, we are working towards removing barriers and aiding in accelerating the adoption of solar power across households and businesses. Ultimately, this is expected to empower more people to embrace the benefits of clean energy while collectively building a greener, more environmentally-conscious India.”

Waaree Energies had an installed PV module manufacturing capacity of 12 GW, as of June 30, 2023 (Source: CRISIL Report). It has four solar module manufacturing facilities in India, with international presence.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoHouse Republicans brace for spring legislative sprint with one less GOP vote

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoAt least four dead in US after dozens of tornadoes rip through Oklahoma

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoStefanik hits special counsel Jack Smith with ethics complaint, accuses him of election meddling

-

Politics7 days ago

Politics7 days agoThe White House has a new curator. Donna Hayashi Smith is the first Asian American to hold the post

-

Politics1 week ago

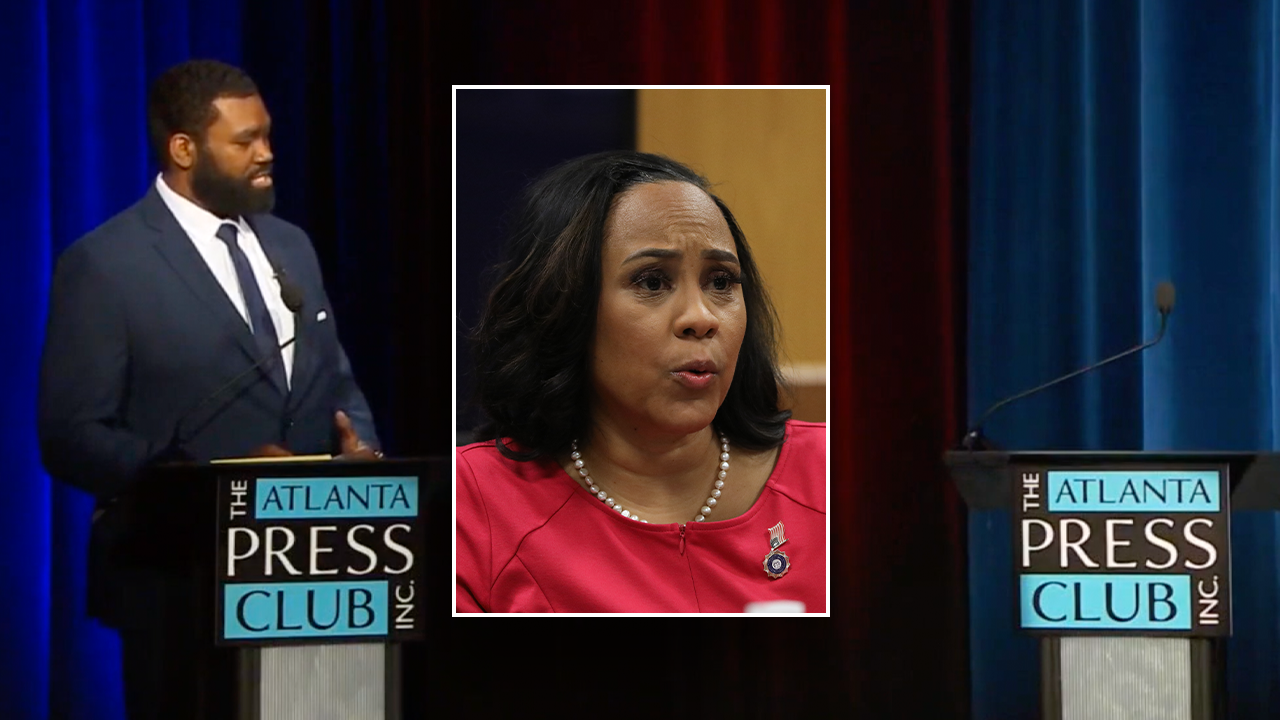

Politics1 week agoAnti-Trump DA's no-show at debate leaves challenger facing off against empty podium

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoAs student protesters get arrested, they risk being banned from campus too

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoVideo: Police Arrest Columbia Protesters Occupying Hamilton Hall

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoNine on trial in Germany over alleged far-right coup plot