Entertainment

Review: Hildegard von Bingen was a saint, an abbess, a mystic, a pioneering composer and is now an opera

Opera has housed a long and curious fetish for the convent. Around a century ago, composers couldn’t get enough of lustful, visionary nuns. Although relatively tame next to what was to follow, Puccini’s 1918 “Suor Angelica” revealed a convent where worldly and spiritual desires collide.

But Hindemith’s “Sancta Susanna,” with its startling love affair between a nun and her maid servant, titillated German audiences at the start of the roaring twenties, and still can. A sexually and violently explicit production in Stuttgart last year led to 18 freaked-out audience members requiring medical attention — and sold-out houses.

Los Angeles Opera got in the act early on. A daring production of Prokofiev’s 1927 “The Fiery Angel,” one of the operas that opened the company’s second season in 1967, saw, wrote Times music critic Martin Bernheimer, “hysterical nuns tear off their sacred habits as they writhe climactically in topless demonic frenzy.”

Now we have, as a counterbalance to a lurid male gaze as the season’s new opera for L.A. Opera’s 40th anniversary season, Sarah Kirkland Snider’s sincere and compelling “Hildegard,” based on a real-life 12th century abbess and present-day cult figure, St. Hildegard von Bingen. The opera, which had its premiere at the Wallis on Wednesday night, is the latest in L.A. Opera’s ongoing collaboration with Beth Morrison Projects, which commissioned the work.

Elkhanah Pulitzer’s production is decorous and spare. Snider’s slow, elegantly understated and, within bounds, reverential opera operates as much as a passion play as an opera. Its concerns and desires are our 21st century concerns and desires, with Hildegard beheld as a proto-feminist icon. Its characters and music so easily traverse a millennium’s distance that the High Middle Ages might be the day before yesterday.

Hildegard is best known for the music she produced in her Rhineland German monastery and for the transcriptions of her luminous visions. But she has also attracted a cult-like following as healer with an extensive knowledge of herbal remedies some still apply as alternative medicine to this day, as she has for her remarkable success challenging the patriarchy of the Roman Catholic Church.

She has further reached broad audiences through Oliver Sacks’ book, “Migraine,” in which the widely read neurologist proposed that Hildegard’s visions were a result of her headaches. Those visions, themselves, have attained classic status. Recordings of her music are plentiful. “Lux Vivens,” produced by David Lynch and featuring Scottish fiddle player Jocelyn Montgomery, must be the first to put a saint’s songs on the popular culture map.

Margarethe von Trotta made an effective biopic of Hildegard, staring the intense singer Barbara Sukowa. An essential biography, “The Woman of Her Age” by Fiona Maddocks, followed Hildegard’s canonization by Pope Benedict XVI in 2012.

Snider, who also wrote the libretto, focuses her two-and-a-half-hour opera, however, on but a crucial year in Hildegard’s long life (she is thought to have lived to 82 or 83). A mother superior in her 40s, she has found a young acolyte, Richardis, deeply devoted to her and who paints representations of Hildegard’s visions. Those visions, as unheard-of divine communion with a woman, draw her into conflict with priests who find them false. But she goes over the head of her adversarial abbot, Cuno, and convinces the Pope that her visions are the voice of God.

Mikaela Bennett, left, as Richardis von Stade and Nola Richardson as Hildegard von Bingen during a dress rehearsal of “Hildegard.”

(Carlin Stiehl / For The Times)

Hildegard, as some musicologists have proposed, may have developed a romantic attachment to the young Richardis, and Kirkland turns this into a spiritual crisis for both women. A co-crisis presents itself in Hildegard’s battles with Cuno, who punishes her by forbidding her to make music, which she ignores.

What of music? Along with being convent opera, “Hildegard” joins a lesser-known peculiar genre of operas about composers that include Todd Machover’s “Schoenberg in Hollywood,” given by UCLA earlier this year, and Louis Andriessen’s perverse masterpiece about a fictional composer, “Rosa.” In these, one composer’s music somehow conveys the presence and character of another composer.

Snider follows that intriguing path. “Hildegard” is scored for a nine-member chamber ensemble — string quartet, bass, harp, flute, clarinet and bassoon — which are members of the L.A. Opera Orchestra. Gabriel Crouch, who serves as music director, is a longtime member of the early music community as singer and conductor. But the allusions to Hildegard’s music remain modest.

Instead, each short scene (there are nine in the first act and five — along with entr’acte and epilogue — in the second), is set with a short instrumental opening. That may be a rhythmic, Steve Reich-like rhythmic pattern or a short melodic motif that is varied throughout the scene. Each creates a sense of movement.

Hildegard’s vocal writing was characterized by effusive melodic lines, a style out-of-character with the more restrained chant of the time. Snider’s vocal lines can feel, however, more conversational and more suited to narrative outline. Characters are introduced and only gradually given personality (we don’t get much of a sense of Richardis until the second act). Even Hildegard’s visions are more implied than revealed.

Under it all, though, is an alluring intricacy in the instrumental ensemble. Still with the help of a couple angels in short choral passages, a lushness creeps in.

The second act is where the relationship between Hildegard and Richardis blossoms and with it, musically, the arrival of rapture and onset of an ecstasy more overpowering than Godly visions. In the end, the opera, like the saint, requires patience. The arresting arrival of spiritual transformation arrives in the epilogue.

Snider has assembled a fine cast. Outwardly, soprano Nola Richardson can seem a coolly proficient Hildegard, the efficient manager of a convent and her sisters. Yet once divulged, her radiant inner life colors every utterance. Mikaela Bennett’s Richardis contrasts with her darker, powerful, dramatic soprano. Their duets are spine-tingling.

Tenor Roy Hage is the amiable Volmar, Hildegard’s confidant in the monastery and baritone David Adam Moore her tormentor abbot. The small roles of monks, angels and the like are thrilling voices all.

Set design (Marsha Ginsberg), light-show projection design (Deborah Johnson), scenic design, which includes small churchly models (Marsha Ginsberg), and various other designers all function to create a concentrated space for music and movement.

All but one. Beth Morrison Projects, L.A. Opera’s invaluable source for progressive and unexpected new work, tends to go in for blatant amplification. The Herculean task of singing five performances and a dress rehearsal of this demanding opera over six days could easily result in mass vocal destruction without the aid of microphones.

But the intensity of the sound adds a crudeness to the instrumental ensemble, which can be all harp or ear-shatter clarinet, and reduces the individuality of singers’ voices. There is little quiet in what is supposed to be a quiet place, where silence is practiced.

Maybe that’s the point. We amplify 21st century worldly and spiritual conflict, not going gentle into that, or any, good night.

‘Hildegard’

Where: The Wallis, 9390 N. Santa Monica Blvd., Beverly Hills

When: Through Nov. 9

Tickets: Performances sold out, but check for returns

Info: (213) 972-8001, laopera.org

Running time: About 2 hours and 50 minutes (one intermission)

Entertainment

10 best art shows across SoCal museums, in a year full of captivating moments

There was no shortage of engrossing art with which to engage in Southern California museums during the past year, although the considerable majority of it had been made only within the past 50 years or so. Art’s global history before the Second World War continues to play a decided second fiddle to contemporary art in special exhibitions.

Our picks for this year’s best in arts and entertainment.

The chief exception: the Getty, where its Brentwood anchor and Pacific Palisades outpost accounted for three of the 10 most engrossing museum exhibitions in 2025, all 10 presented here in order of their opening dates. (Four are still on view.)

Art museums across the country continue to struggle in attendance and fundraising after the double-whammy of the lengthy COVID-19 pandemic shut-down followed by culture war attacks from the Trump administration. That may help explain the unusually lengthy, seven-to-14 month duration of half of these shows.

Gustave Caillebotte, “Floor Scrapers,” 1875, oil on canvas.

(Musée d’Orsay / Patrice Schmidt

)

Gustave Caillebotte: Painting Men. Getty Center

An emphasis on men’s daily lives is very unusual in French Impressionist art. Women are more prominent as subject matter in scores of paintings by marquee names like Monet, Cassatt and Degas. But homosocial life in late-19th century Paris was the fascinating focus of this show, the first Los Angeles museum survey of Gustave Caillebotte’s paintings in 30 years.

A view into a dance gallery is framed by Guadalupe Rosales’ “Concourse/C3” installation.

(Christopher Knight / Los Angeles Times)

Guadalupe Rosales – Tzahualli: Mi Memoria en Tu Reflejo. Palm Springs Art Museum

Vibrant Chicano youth subcultures of 1990s Los Angeles, during the fraught era of Rodney King and the AIDS epidemic, are embedded in the art of one of its enthusiastic participants. Guadalupe Rosales layers her archival work onto pleasure and freedom today, as was seen in this vibrant exhibition, offering a welcome balm during another period of outsized social distress.

Don Bachardy, “Christopher Isherwood,” June 20, 1979; acrylic on paper.

(Don Bachardy Paper / Huntington Library)

Don Bachardy: A Life in Portraits. The Huntington

The nearly 70-year retrospective of portrait drawings in pencil and paint by Los Angeles artist Don Bachardy revealed the works to be like performances: Both artist and sitter participated in putting on a pictorial show. The extended visual encounter between two people, its intimacy inescapable, culminates in the two “actors” autographing their performed picture.

“Probably Shakyamuni, the Historical Buddha,” China, Tang Dynasty, circa 700-800; marble.

(Christopher Knight / Los Angeles Times)

Realms of the Dharma: Buddhist Art Across Asia. LACMA. Through July 12

“Realms of the Dharma” isn’t exactly an exhibition. Instead, it’s a temporary, 14-month installation of Buddhist sculptures, paintings and drawings from the museum’s impressive permanent collection, plus a few additions. It’s worth noting here, though, because almost all of its marvelous pieces were in storage (or traveling) for more than seven years, during the lengthy tear-down of a prior LACMA building and construction of a new one, and much of it will disappear again when the installation closes next summer.

Noah Davis, “40 Acres and a Unicorn,” 2007, acrylic and gouache on canvas.

(Anna Arca)

Noah Davis. UCLA Hammer Museum

A tight survey of 50 works, all made by Noah Davis in the brief span between 2007 and the L.A.-based artist’s untimely death in 2015 at just 32, told a poignant story of rapid artistic growth brutally interrupted. Davis was a painter’s painter, a deeply thoughtful and idiosyncratic Black voice heard by other artists and aficionados, even while still in invigorating development.

Weegee (Arthur Fellig), “The Gay Deceiver, 1939/1950, gelatin silver print. Getty Museum

(Getty Museum)

Queer Lens: A History of Photography. Getty Center

Assembling some 270 photographs from the 19th and 20th centuries, “Queer Lens” looked at work produced after the 1869 invention of the binaries of “heterosexual and homosexual,” just a short generation after the 1839 invention of the camera. Transformations in the expression of gender and sexuality by scores of artists as well-known as Berenice Abbott, Anthony Friedkin, Robert Mapplethorpe, Man Ray and Edmund Teske were tracked along with more than a dozen unknowns.

“Sealstone With a Battle Scene (The Pylos Combat Agate),” Minoan, 1630-1440 BC; banded agate, gold and bronze.

(Jeff Vanderpool)

The Kingdom of Pylos: Warrior-Princes of Ancient Greece. Getty Villa. Through Jan. 12

The star of this look into the ancient, not widely known Mycenaean kingdom of Pylos was a tiny agate, barely 1.3 inches wide, making its public debut outside Europe. The exquisitely carved stone, unearthed by archaeologists in 2017, shows two lean but muscled warriors going at it over the sprawled body of a dead comrade. Perhaps made in Crete, the idealized naturalism of a battle scene rendered in shallow three-dimensional space threw a stylistic monkey-wrench into our established understanding of Greek culture 3,500 years ago.

Ken Gonzales-Day digitally erased Illinois Black lynching victim Charlie Mitchell from an 1897 postcard to focus instead on the perpetrators.

(USC Fisher Museum of Art)

Ken Gonzales-Day: History’s “Nevermade.” USC Fisher Museum of Art. Through March 14

The ways in which identities of race, gender and class are erased in a society dominated by straight white patriarchy animates the first mid-career survey of Los Angeles–based artist Ken Gonzales-Day. The riveting centerpiece is his extensive meditation on the American mass-hysteria embodied by the horrific practice of lynching, in which Gonzales-Day employed digital techniques to erase the brutalized victims (and the ropes) in grisly photographs of the murders. Focus shifts the viewer’s gaze toward the perpetrators — an urgent and timely transference, given the shredding of civil society underway today.

Kara Walker deconstructed a monument to Confederate Gen. Stonewall Jackson for “Unmanned Drone,” as seen at the Brick gallery as part of “Monuments.”

(Etienne Laurent / For The Times)

Monuments. The Geffen Contemporary at MOCA and the Brick. Through May 3

The nearly two-year delay in opening “Monuments,” an exhibition of toppled Confederate and Jim Crow statues that pairs cautionary art history with thoughtful and poetic retorts by a variety of artists, turned out to give the much anticipated undertaking an especially potent punch. As the Trump Administration restores a white supremacist sheen to “Lost Cause” mythology by renaming military installations after Civil War traitors and returning sculptures and paintings of them to prior perches, from which they had been removed, this sober and incisive analysis of what’s at stake is nothing less than crucial.

Peak moment: As a metaphor of white supremacy, Kara Walker’s transformation of the ancient “man on a horse” motif into a monstrous headless horseman — a Euro-American corpse that tortures the living and refuses to die — resonates loudly.

Installation view of sculptures and a painting by Robert Therrien at the Broad.

(Joshua White / Broad museum)

Robert Therrien: This Is a Story. The Broad. Through April 5

The late Los Angeles-based artist Robert Therrien (1947-2019) had a distinctive, even quirky capacity for teasing out a conceptual space between ordinary domestic objects and their mysterious personal meanings. In 120 paintings, drawings, photographs and especially sculptures, this Therrien exhibition offers objects hovering somewhere between immediately recognizable and perplexingly alien, wryly funny and spiritually profound.

Movie Reviews

Movie review: Jay Kelly – Baltimore Magazine

They say write what you know, which is probably why there are so many damn films about Hollywood. The latest navel-gazer, Jay Kelly, is about an aging movie star (played, not coincidentally, by aging movie star George Clooney) reflecting on his life and his choices. The film is directed with care and style and generous (if occasionally gimmicky) wit by Noah Baumbach and the performances by both Clooney and Adam Sandler as Ron Sukenick, Jay’s long-suffering manager, are excellent. But a little part of me was like, remind me again why I’m supposed cares about this vain multimillionaire and his extremely niche problems?

Having just wrapped his latest film, the 60-year-old Jay is having an existential crisis, of sorts. It has dawned on him that he spent so much time building his career, his life is empty. He’s neglected the two most important relationships of his life, namely with his daughters. He doesn’t really know who he is beyond the glamorous façade and he has no real friends, other than Ron, who is on the payroll.

If you’re thinking this all sounds a bit familiar that’s because a very similar film came out of Norway earlier this season, Sentimental Value. I’m not going to make broad generalizations about American vs. European films—especially since Baumbach is the spiritual successor to Woody Allen who was deeply influenced by the European greats—but suffice it to say that the Norwegian one, which focused mainly on the inner lives of the abandoned daughters, was better.

The crux of Jay Kelly is that our titular hero is always surrounded by a coterie that includes his manager, a stylist (Emily Mortimer, who co-wrote the script), a bodyguard-cum-butler, a publicist (Laura Dern), and various other hangers on, but he’s supremely lonely. (An on-going joke has Jay complaining he’s always alone just as his bodyguard hands him a cold drink.)

And Ron is beginning to reassess his devotion to Jay. He’s given the better part of his life to this man—willing to drop any other commitment, including to his own children, on a dime to attend to him—but was it all worth it? Are they even friends?

“Friends don’t take 15 percent,” Jay snaps to Ron during one particularly bruising fight.

But at least Ron still has his family—although his wife (Baumbach’s real-life partner Greta Gerwig in what amounts to an extended cameo) blames him for their daughter’s almost debilitating anxiety. Jay, however, is essentially on his own. His oldest daughter, Jessica (Riley Keough), has all but given up on him. “You know how I know you didn’t want to spend time with me?” she asks him bitterly. “Because you didn’t spend time with me.”

Oof.

And he now he finds himself desperate to connect with his younger daughter, Daisy (Grace Edwards), who is about to embark on a European vacation with her friends before heading off for college.

Daisy has more fondness, or at least more patience, with her dad—she finds him amusing—but she isn’t going to suddenly disrupt her life to spend time with him. She heads off on her own.

Jay Kelly occasionally employs an A Christmas Carol-style structure where Jay revisits pivotal scenes of his life. One comes after he finds out that the director who gave him his first big break, Peter Scheider (Jim Broadbent), has died. Jay is indebted to Schneider, or should be, at least—and they’ve remained friends. But one of those flashbacks has Schneider begging Jay to do his latest film, as he needs the money. With a kind of cold efficiency masking as kindness, Jay refuses him. We see this a lot with Jay. He is good at indicating friendship and generosity of spirit, but there’s no substance behind his cheer.

At Schneider’s funeral, Jay reconnects with his old acting school roommate, Timothy (Billy Crudup). Turns out, despite his eagerness to grab a beer, Timothy despises Jay—blames him for stealing his life. It is, in fact, not an exaggeration. In another flashback we see cocky young Jay (now played by Charlie Rowe, not quite convincingly) snatch an audition for Schneider’s film right out from under Timothy (Louis Partridge), even using Timothy’s own improvements to the script that Timothy was too shy to incorporate. (The suggestion here is twofold: Yes, Jay stole from Timothy. But also, Jay had the kind of ballsiness to make those embellishments to the script. When he tells Timothy he didn’t have what it took, was he possibly…right?)

Finding out that his old friend, about whom he has warmly nostalgic feelings, actually hates his guts is another turning point for Jay. He’s more determined than ever to repair his relationship with Daisy—perhaps his last hope for redemption—so decides to track her down in Europe, using a lifetime achievement award he’ll be receiving from the Tuscan Film Festival as his excuse.

In one of the film’s most irritating scenes, he is forced to take a train from Paris to Rome with the actual little people, who are depicted as kindly, salt-of-the-earth types; a train full of Mrs. Clauses and Geppettos. Jay watches them, moist-eyed, thinking this is what he has missed in life. It’s beyond patronizing, although Baumbach adds a small dose of reality when someone points out to Jay that the people are on their best behavior because they’re in front of a movie star. Later in the train ride, Jay pulls a Tom Cruise and catches a purse snatcher—it’s a clear inside joke as Clooney even does Cruise’s intense, arm pumping run to catch up to him. Jay is hailed as a hero, but even that is complicated. The man who stole the purse isn’t a hardened criminal but a family man off his meds. (Again, it felt like Baumbach was fighting against his own impulses in that scene.)

Recently, after watching Jerry Maguire for the first time in years, I complained that they didn’t make middlebrow films like that anymore—that is, smart and satisfying, if somewhat facile, films for grownups. This is definitely that. And there’s excellent here work from Clooney, who gives arguably his best performance ever in this a meta dissection of his own career and of the strange paradox of having a life that belongs to everyone but yourself.

[WARNING: HERE COMES A SPOILER OF SORTS BECAUSE I WANT TO DISCUSS THE FINAL SCENE]

Jay Kelly is ultimately a film about a man living with the consequences of his own narcissism but the final scene, at the Tuscan film festival, does hedge its bets a bit: We see a montage of Jay/Clooney’s films and it brings tears to his eyes. He was great. He did move people. It was a wonderful life, in its own way. He’s so touched by what he sees on screen that he reaches out for the hand of a loved one—but there’s only Ron, so he clutches his hand instead. It’s both sad and kind of beautiful. The film has sneakily been a love story between these two hollow men the whole time.

Entertainment

Review: ‘Zodiac Killer Project’ pursues a doc never made, revealing a filmmaker’s own obsession

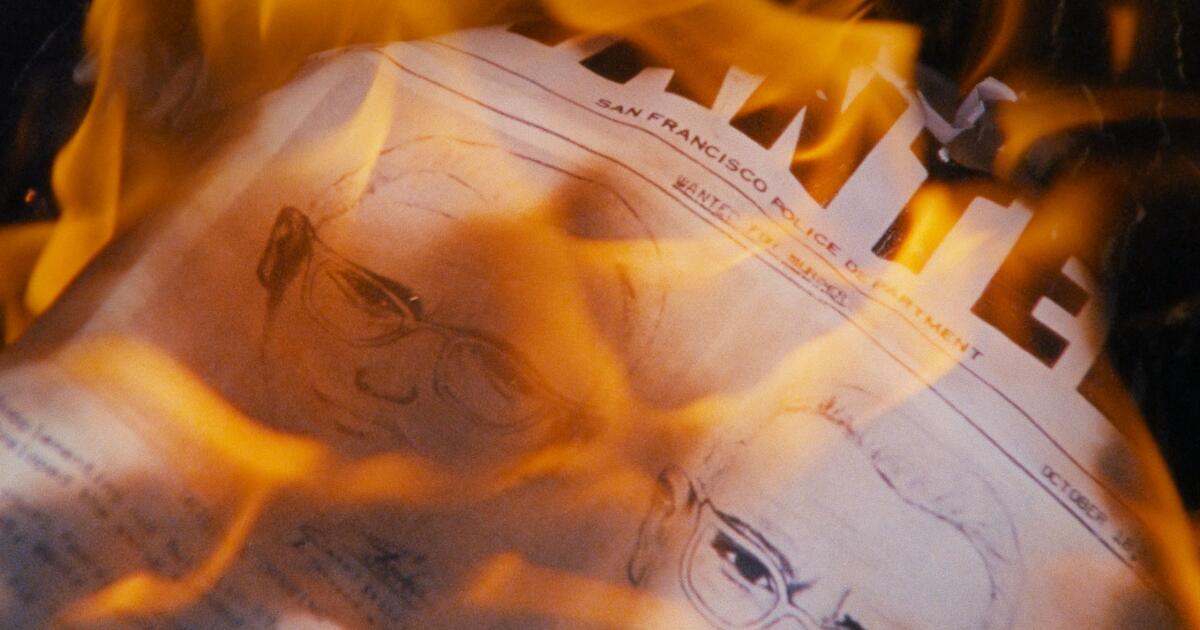

No mystery is solved in Charlie Shackleton’s essayistic doodad “Zodiac Killer Project,” but the true-crime genre itself is certainly staked out and interrogated like a prime suspect. Then again, there’s nothing like the tweezer focus of an obsessive — either trying to crack a maddening case or devouring shows about them on Netflix — to put our darker yearnings for fulfillment on queasy display, while reveling in minutiae at the same time.

Shackleton, a British filmmaker with an avant-garde sensibility, was all set to make his own opus, based on the investigative musings of a Vallejo cop who believed he’d discovered the identity of the infamous Zodiac killer who terrorized the Bay Area in the late ’60s, taunting police with letters and cryptograms, never to be caught. Shackleton’s fascination with former highway patrol officer Lyndon Lafferty’s speculative memoir “The Zodiac Killer Cover-Up,” which details a years-long quest to bring his pinpointed suspect to justice in the face of a perceived conspiracy, led to a bid for the rights. When that fell through, a different film project emerged.

Composed of original footage and the director’s conversational voice-over, “Zodiac Killer Project” is the chalk outline of his missing and presumed dead documentary. Shackleton explains his conceptual framework for it over long takes of serene, sunny Vallejo locations: an empty parking lot, a church, an intersection, a wooded house. We hear what perfectly designed re-creation he would have mounted there — or, since these aren’t necessarily the sites specified in Lafferty’s narrative and Shackleton is nothing if not honest, filmed at a place just like it.

In one sense, what we’re watching is a wittily rueful pitch session for an Errol Morris-style homage that never was, flecked with inserts we learn are called “evocative b-roll” (the swinging overhead lamp, the gun in someone’s hand), shots meant to be artfully slotted alongside his imagined interviews with key participants. Shackleton, glimpsed on camera in the studio where he vamped his narration, knows his act breaks and thematic beats.

And yet his abandoned undertaking is also a mischievous explosion of a storytelling format, a knowing critique of this most-wanted genre’s longstanding tropes: the eerie credit sequences, montages and music cues. Don’t expect a rehash of the Zodiac case, nor the parts of Lafferty’s book he can’t legally talk about. Settle in for some amusing dissections of popular docuseries like “Making a Murderer” and “The Jinx,” as well as the simultaneously moralizing and exploitative “Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story.”

Of course, Shackleton is an openly avid connoisseur of those titles too, and it’s sometimes difficult to discern from the glibness of his tone whether he’s pointing the finger at himself or pining over rejection from a club he clearly wanted to join. That can leave the occasionally repetitive “Zodiac Killer Project” with a shallow aftertaste to go with its smarts. But in a year that’s seen a valuable rethink of how we process crime stories — from the eye-opening documentaries “Predators” and “The Perfect Neighbor” to Caroline Fraser’s deeply researched book “Murderland” — Shackleton’s perspective is still an intriguing, worthy provocation regarding our cultural bloodlust.

‘Zodiac Killer Project’

Not rated

Running time: 1 hour, 32 minutes

Playing: Opens Friday, Dec. 5 at Alamo Drafthouse DTLA and Laemmle Glendale

-

Alaska2 days ago

Alaska2 days agoHowling Mat-Su winds leave thousands without power

-

Ohio4 days ago

Who do the Ohio State Buckeyes hire as the next offensive coordinator?

-

Politics6 days ago

Politics6 days agoTrump rips Somali community as federal agents reportedly eye Minnesota enforcement sweep

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoTrump threatens strikes on any country he claims makes drugs for US

-

World6 days ago

World6 days agoHonduras election council member accuses colleague of ‘intimidation’

-

Texas2 days ago

Texas2 days agoTexas Tech football vs BYU live updates, start time, TV channel for Big 12 title

-

Politics6 days ago

Politics6 days agoTrump highlights comments by ‘Obama sycophant’ Eric Holder, continues pressing Senate GOP to nix filibuster

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoWar Sec Pete Hegseth shares meme of children’s book character firing on narco terrorist drug boat