Movie Reviews

Dream Scenario movie review: (un)likely boogeyman – FlickFilosopher.com

The term “Cage rage” is used, approvingly, by fans of the over-the-top acting style that Nicolas Cage sometimes deploys in his film performances, usually in movies that feature extreme violence and explore deranged personalities: there’s lots of unhinged fury, often drenched in blood, as his eyes bulge and he screams furiously. Ethan Hawke, in a 2013 AMA on Reddit, praised Cage’s approach: “He’s the only actor since Marlon Brando that’s actually done anything new with the art of acting; he’s successfully taken us away from an obsession with naturalism.”

Indeed, Cage told Indiewire in a 2018 interview that his technique is “all very thought out and carefully planned,” an expression of his “abstract and more ontological fantasies with film performance.” So the actor finds it “frustrating” and a “disservice” to the films and his work that those performances are often detached from their cinematic contexts and edited by fans into clip collections, or supercuts: long montages of, well, Cage rage. These amuse fans. They don’t amuse Cage.

So it’s easy to see what may have drawn Cage to Dream Scenario, and why he’s so profoundly moving in it. I only wish the film was more deserving of what he’s doing here.

Cage (Sympathy for the Devil, Renfield) plays extremely mildmannered college professor Paul Matthews, a nobody of a man who, for mysterious and unexplained reasons, suddenly starts appearing in the dreams of people all over the world. People he doesn’t know and who have no way of knowing him. He doesn’t do anything in the dreams, just observes whatever surreal oddness is occuring. The phenomenon itself is beyond dreamlike oddness, to say the least, and once it becomes known that the strange man everyone is seeing in their dreams is the same individual, an actual real person, Paul becomes a bit of a media sensation, to his baffled but also, maybe, secretly pleased surprise.

This is not a Cage-rage performance — quite the opposite. Cage is so naturalistic, so down-to-earth that he frequently and completely appropriately induces cringes in the viewer with Paul’s utterly human awkwardness and his banal desperation to be liked. His work here is comedic in the driest, subtlest, most nakedly painful way, very much akin to his brilliant turn in 2002’s Adaptation. And it becomes even more so when “Paul’s” benign presence in people’s dreams turns nasty and violent, and suddenly this harmless schlub has become a menacing figure lodged in the collective subconscious, one that also terrifies those dreamers in a way that carries over to their waking minds.

Now, it’s explicit that Norwegian writer-director Kristoffer Borgli wants to examine modern concepts of fame, especially when it is unexpected and unwanted. “How does it feel to go viral?” one of Paul’s students asks. (This is Borgli’s third feature, and his first wholly in the English language. His 2022 film Sick of Myself and his 2014 short “Internet Famous” both appear to consider similar themes; I haven’t seen either, though Sick is high on my watchlist.) But where the filmmaker takes it from here never quite gelled for me. Metaphors don’t have to be perfect analogs to be effective, of course, but it seems to me that even unexpected and unwanted fame is the result of overt actions on someone’s part, even if they never wanted those actions to be made quite so public. Just because, say, a surreptitiously shot video of an angry Karen demanding to speak to a manager went viral doesn’t mean that it’s not an accurate representation of her behavior.

But poor Paul! People are suddenly terrified of him — are, ahem, cancelling him, even — because of something that isn’t real, that he didn’t do, and that bears no resemblance whatsoever to anything he would do. Paul wouldn’t mind some recognition for his work: his field is the evolutionary biology of insects, and he has a book about “antelligence” that he’d love to write and get a little bit famous for, but he’s so ineffectual that the book is only the germ of an idea right now. Paul isn’t even a threat to his own procrastinating ineptitude, never mind to anyone else.

Cage crafts a palpable misery in Paul’s, well, stuckness in his own life, in his befuddled benign neglect of himself, and in his own clueless lack of self-awareness. This is a horror movie in which the horror is the protagonist’s own insipid inability to follow through on his ambitions, which he probably can’t even see. And there are extra layers of horror for a viewer who may see him- or her- or themself in that incredibly common aspect of Paul’s personality. Borgli and cinematographer Benjamin Loeb add to that heavy weight with a carefully studied atmosphere of intentional drabness: Paul’s reality isn’t merely mundane, it’s muted and gray.

On the other hand, the violent dreams Paul appears in are practically parodies of memeified “Cage rage.” Surely the actor’s own displeasure with how his work is sometimes received fuels his portrayal of both dream-Paul’s outrageous violence and actual-Paul’s bewilderment at how his dream “audience” responds.

But that’s tangential, behind-the-scenes color, and not anything to do with what Dream Scenario is actually about. And, sadly, the longer Dream Scenario goes on, the less confident Borgli is about any of it. The only vibe I was getting — and this snuck up on me until it felt like an unpleasant certainty — is one not of the vagaries of fame but the terror too many men have now that our society is beginning to hold them to account for their bad behavior, such as with the #MeToo movement, and how we’re starting to talk about rape culture as a thing to be deconstructed and dismantled.

Of course, hashtag–not all men. Not Paul! He’s harmless, as we can plainly see. Wouldn’t hurt a fly, truly. And yet people — men as well as women — are suddenly afraid of him merely because they imagined him doing something awful. It’s not right. It’s unfair!

And it is unfair. Paul doesn’t deserve what he gets here. People may behave strangely in dreams, but the way people around Paul — such as his wife, Janet (Julianne Nicholson: I, Tonya, Black Mass) — react in the dull mundanity of his real world ultimately makes little sense and feels wildly implausible. Not that fictional characters always have to deserve what they get… but what they get should at least make a sort of narrative sense. But here, either the calculus of Borgli’s tale is off and he derailed his own intriguing concept because he didn’t know where to take it… or he really is saying, “Won’t someone think of the trauma men are going through now that women have stopped pretending we don’t have good reasons to be afraid of some of you?”

Alas, it isn’t mere nightmares that have made women finally speak our truths, and even given that, no man is getting “cancelled” — not that that even actually happens, certainly not like it does for Paul here — for no reason whatsoever. Men who have done bad things are, very occasionally, having to face consequences. Plenty of men are still getting away with their crimes. Innocent men are not being targeted, unfairly or otherwise.

I haven’t been a fan of Cage’s “Cage-rage” performances; I’ve characterized them in the past as “indulging tropes of toxic masculinity,” though I might reconsider that in light of Hawke’s praise. But what we see in Dream Scenario, which looks a helluva lot like it’s straining to build up a strawman siege of poor Paul? That is pretty toxic.

more films like this:

• Being John Malkovich [Prime US | Prime UK | Apple TV]

• Inception [Prime US | Prime UK | Apple TV | BFI Player UK]

Movie Reviews

Film Review: The Fire Inside – SLUG Magazine

Film

The Fire Inside

Director: Rachel Morrison

Michael De Luca Productions, PASTEL

In Theaters: 12.25

I’m not a fan of combat sports in real life, yet I find that movies about them are nearly irresistible. Whether it’s Rocky, The Karate Kid, Warrior or the upcoming wrestling flick Unstoppable, the underdog who comes out swinging and bests their bigger, more experienced opponent always plays. It’s also nearly always the same movie, and that’s what makes The Fire Inside a knockout.

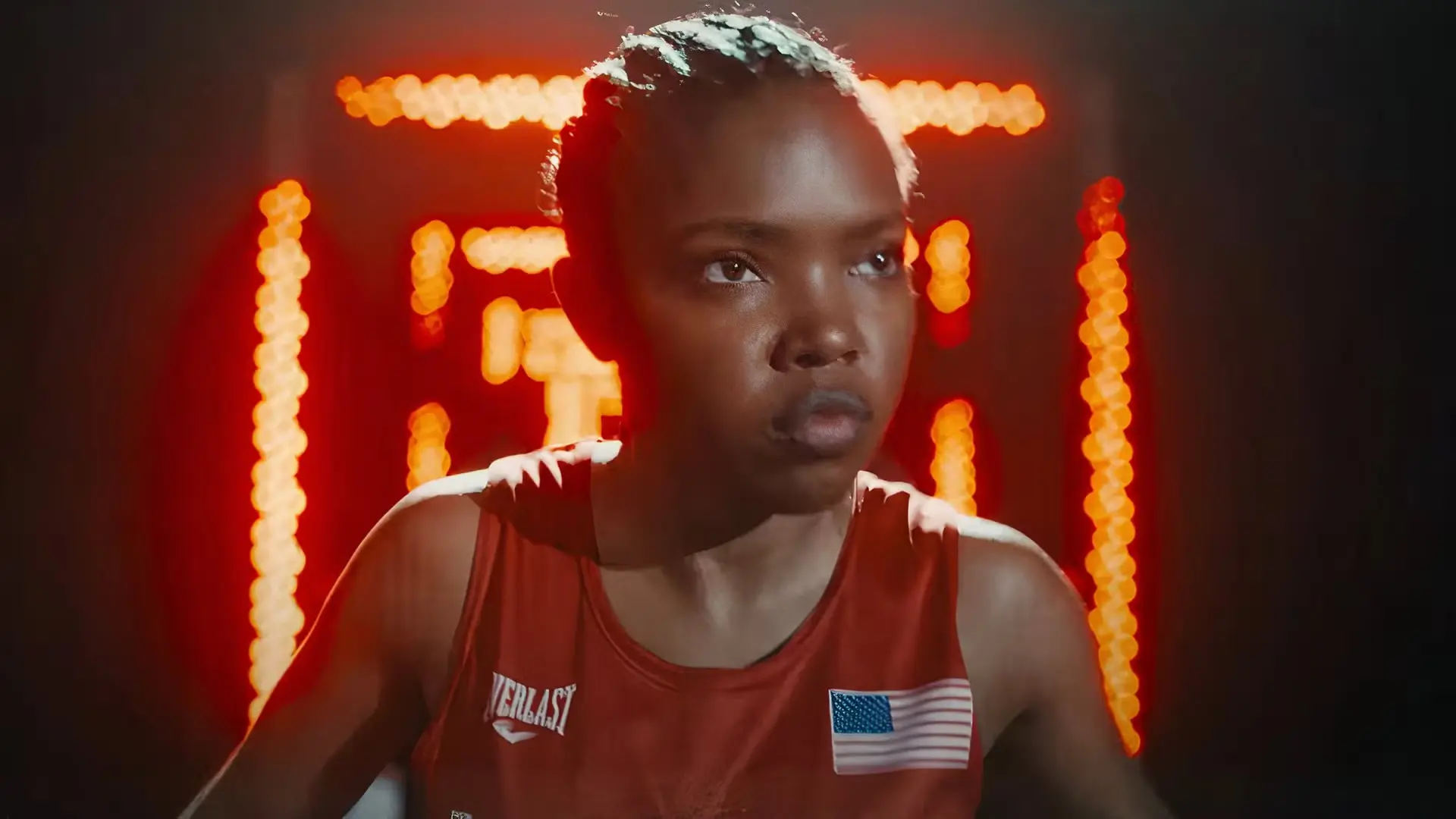

In this fact–based story, Claressa Shields (Ryan Destiny, A Girl Like Grace, Oracle) is a young woman from Flint, Michigan, who has one skill and one passion: boxing. Despite limited support from her family, Claressa is taken under the wing of Jason Crutchfield (Brian Tyree Henry, If Beale Street Could Talk, Godzilla vs. Kong), a coach at a local gym. As Jason becomes as much a surrogate father as a coach, Claressa trains with a ferocious determination and earns a spot on the 2012 Summer Olympic team — Claressa “T-Rex” Shields becomes the first American woman to take home the gold in the sport at age 16. From there, Claressa goes from being a poor inner city kid with nothing to … a poor inner city kid with a gold medal overnight. There are no endorsement deals, no professional career and seemingly no new worlds to conquer. As Claressa fights discouragement, she must find a path to lead her beyond a one time victory into a lasting better life.

Rachel Morrison, the first woman to be nominated for an Academy Award for her work on Black Panther, makes a strong directorial debut, coming out swinging. She’s ably assisted by a terrific script by Barry Jenkins (Moonlight). The Fire Inside transcends the tropes of the genre by reaching the rush of climactic fight and then daring not to end there, instead delving into the reality that in Shields’ life, one triumph in the sports world doesn’t change your circumstances, especially for an uncouth young woman with no interest in playing the public relations game and selling a softer, more traditionally feminine image. We’ve heard the cliche “this isn’t just a movie about sports, it’s about life,” but such a candid look at a life-changing moment that does nothing to change your life, and learning how to face this, was something refreshingly new and honest. The often bleak and at times stunningly beautiful cinematography by Rina Yang, along with the stirring score by Tamar-kali, lift the sensory experience and go a long way to making this one a winner.

Destiny shows potential as a breakout star, commanding the screen as effortlessly as Claressa commands the ring. Henry is the highlight of any film he’s in, and The Fire Inside is no exception, with his grounded performance keeping the film moving along and setting the tone for a story about learning that you can still lean on others while you’re believing in yourself. The sizzling chemistry between these two actors drives a poignant and entertaining story to a satisfying and believable conclusion that’s not the one you’re expecting.

The Fire Inside is a breath of fresh air in a genre that far too often settles for stale and dank. It provides enough inspirational warmth to fulfill its duties as an uplifting sports movie, but its got the stamina and the drive to go a few extra rounds and push its own limits. Unlike most boxing films, this champ doesn’t pull any punches. –Patrick Gibbs

Read more film reviews here:

Film Review: A Complete Unknown

Film Review: Babygirl

Movie Reviews

Movie review: Reverence to source material drains life from ‘Nosferatu’

Passion projects are often lauded simply for their passion, for the sheer effort that it took to bring a dream to life. Sometimes, that celebration of energy expended can obfuscate the artistic merits of a film, as the blinkered vision of a dedicated auteur can be a film’s saving grace, or its death knell. This is one of the hazards of the passion project, which is satirically explored in the 2000 film “Shadow of the Vampire,” a fictionalized depiction of the making of F.W. Murnau’s 1922 silent horror film “Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror,” in which John Malkovich plays the filmmaker obsessed with “authentic” horror.

This meta approach is a clever twist on the iconic early horror movie that looms large in our cultural memory. Inspired by Bram Stoker’s 1897 novel “Dracula” (with names and details changed in order to skirt the lack of rights to the book), “Nosferatu” is a landmark example of German Expressionism, and Max Schreck’s performance as the vampire is one of the genre’s unforgettable villains.

“Nosferatu” has inspired many filmmakers over a century — Werner Herzog made his own bleak and lonely version with Klaus Kinski in 1979; Francis Ford Coppola went directly to the source material for his lushly Gothic “Bram Stoker’s Dracula” in 1992. Now, Robert Eggers, who gained auteur status with his colonial horror film “The Witch,” the Edgar Allen Poe-inspired two-hander “The Lighthouse,” and a Viking epic “The Northman,” delivers his ultimate passion project: a direct remake of Murnau’s film.

His first non-original screenplay, Eggers’ version isn’t a “take” on “Nosferatu,” so much as it is an overly faithful retelling, so indebted to its inspiration that it’s utterly hamstrung by its own reverence. If “Shadow of the Vampire” is a playful spin, Eggers’ “Nosferatu” is an utterly straight-faced and interminably dull retread of the 1922 film. It’s the exact same movie, just with more explicit violence and sex. And while Eggers loves to pay tribute to the style and form of cinema history in his work, the sexual politics of his “Nosferatu” feel at least 100 years old.

“Nosferatu” is a story about real estate and sexual obsession. A young newlywed, Thomas Hutter (Nicholas Hoult) is dispatched from his small German city to the Carpathian Mountains in order to execute the paperwork on the purchase of a rundown manor for a mysterious Count Orlok (an unrecognizable Bill Skarsgård), a tall, pale wraith with a rumbling voice that sounds like a beehive.

Thomas has a generally bad time with the terrifying Count Orlok, while his young bride at home, the seemingly clairvoyant Ellen (Lily-Rose Depp) is taken with terrifying nightmares and bouts of sleepwalking, consumed by psychic messages from the Count, who has become obsessed with her. He makes his way to his new home in a rat-infested ship, unleashing a plague; Ellen weighs whether she should sacrifice herself to the Count in order to save the town, which consists of essentially three men: her husband, a doctor (Ralph Ineson) and an occultist scientist (Willem Dafoe).

There’s a moment in the first hour of “Nosferatu” where it seems like Eggers’ film is going to be something new, imbued with anthropological folklore, rather than the expressionist interpretation of Murnau. Thomas arrives in a Romanian village, where he encounters a group of jolly gypsies who laugh at him, warn him, and whose blood rituals he encounters in the night. It’s fascinating, fresh, culturally specific, and a new entry point to this familiar tale. Orlok’s mustachioed visage could be seen as a nod to the real Vlad the Impaler, who likely inspired Stoker.

But Eggers abandons this tack and steers back toward leaden homage. The film is a feat of maximalist and moody production design and cinematography, but the tedious and overwrought script renders every character two-dimensional, despite the effortful acting, teary pronunciations and emphatically delivered declarations.

Depp whimpers and writhes with aplomb, but her enthusiastically physical performance never reaches her eyes — unless they’re rolling into the back of her head. Regardless of their energetic ministrations, she and Hoult are unconvincing. Dafoe, as well as Aaron Taylor-Johnson and Emma Corrin, as family friends who take in Ellen, bring a winking campiness, breathing life into the proceedings, while Simon McBurney devilishly goes for broke as the Count’s familiar. However, every actor seems to be in a different movie.

Despite the sex, nudity and declarations of desire, there’s no eroticism or sensuality; despite the blood and guts, there’s nothing scary about it either. This film is a whole lot of style in search of a better story, and without any metaphor or subtext, it’s a bore. Despite his passion for the project, or perhaps because of it, Eggers’ overwrought “Nosferatu” is dead on arrival, drained of all life and choked to death on its own worship.

‘Nosferatu’

GRADE: C

Rated R: for bloody violent content, graphic nudity and some sexual content

Running time: 135 minutes

In theaters Dec. 25

Movie Reviews

Movie Review: Nicole Kidman commands the erotic office drama Babygirl

The demands of achieving both one-day shipping and a satisfying orgasm collide in Halina Reijn’s “Babygirl,” a kinky and darkly comic erotic thriller about sex in the Amazon era.

Nicole Kidman stars as Romy Mathis, the chief executive of Tensile, a robotics business that pioneered automotive warehouses. In the movie’s opening credits, a maze of conveyor belts and bots shuttle boxes this way and that without a human in sight.

Romy, too, is a little robotic. She intensely presides over the company. Her eyes are glued to her phone. She gets Botox injections, practices corporate-speak presentations (“Look up, smile and never show your weakness”) and maintains a floor-through New York apartment, along with a mansion in the suburbs that she shares with her theater-director husband ( Antonio Banderas ) and two teenage daughters (Esther McGregor and Vaughan Reilly).

But the veneer of control is only that in “Babygirl,” a sometimes campy, frequently entertaining modern update to the erotically charged movies of the 1990s, like “Basic Instinct” and “9 ½ Weeks.” Reijn, the Danish director of “Bodies Bodies Bodies” has critically made her film from a more female point of view, resulting in ever-shifting gender and power dynamics that make “Babygirl” seldom predictable — even if the film is never quite as daring as it seems to thinks it is.

The opening moments of “Babygirl,” which A24 releases Wednesday, are of Kidman in close-up and apparent climax. But moments after she and her husband finish and say “I love you,” she retreats down the hall to writhe on the floor while watching cheap, transgressive internet pornography. The breathy soundtrack, by the composer Cristobal Tapia de Veer, heaves and puffs along with the film’s main character.

One day while walking into the office, Romy is taken by a scene on the street. A violent dog gets loose but a young man, with remarkable calmness, calls to the dog and settles it. She seems infatuated. The young man turns out to be Samuel (Harris Dickinson), one of the interns just starting at Tensile. When they meet inside the building, his manner with her is disarmingly frank. Samuel arranges for a brief meeting with Romy, during which he tells her, point blank, “I think you like to be told what to do.” She doesn’t disagree.

Some of the same dynamic seen on the sidewalk, of animalistic urges and submission to them, ensues between Samuel and Romy. A great deal of the pleasure in “Babygirl” comes in watching Kidman, who so indelibly depicted uncompromised female desire in Stanley Kubrick’s “Eyes Wide Shut,” again wade into the mysteries of sexual hunger.

“Babygirl,” which Reijn also wrote, is sometimes a bit much. (In one scene, Samuel feeds Romy saucers of milk while George Michael’s “Father Figure” blares.) But its two lead actors are never anything but completely magnetic. Kidman deftly portrays Romy as a woman falling helplessly into an affair; she both knows what she’s doing and doesn’t.

Dickinson exudes a disarming intensity; his chemistry with Kidman, despite their quickly forgotten age gap, is visceral. As their affair evolves, Samuel’s sense of control expands and he begins to threaten a call to HR. That he could destroy her doesn’t necessarily make Romy any less interested in seeing him, though there are some delicious post-#MeToo ironies in their clandestine CEO-intern relationship. Also in the mix is Romy’s executive assistant, Esme (Sophie Wilde, also very good), who’s eager for her own promotion.

Where “Babygirl” heads from here, I won’t say. But the movie is less interested in workplace politics than it is in acknowledging authentic desires, even if they’re a little ludicrous. There’s genuine tenderness in their meetings, no matter the games that are played. Late in the film, Samuel describes it as “two children playing.”

As a kind of erotic parable of control, “Babygirl” is also, either fittingly or ironically, shot in the very New York headquarters of its distributor, A24. For a studio that’s sometimes been accused of having a “house style,” here’s a movie that goes one step further by literally moving in.

What about that automation stuff earlier? Well, our collective submission to digital overloads might have been a compelling jumping-off point for the film, but along the way, not every thread gets unraveled in the easily distracted “Babygirl.” Saucers of milk will do that.

“Babygirl,” an A24 release, is rated R by the Motion Picture Association for “strong sexual content, nudity and language.” Running time: 114 minutes. Three stars out of four.

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoFreddie Freeman's World Series walk-off grand slam baseball sells at auction for $1.56 million

-

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23951353/STK043_VRG_Illo_N_Barclay_3_Meta.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23951353/STK043_VRG_Illo_N_Barclay_3_Meta.jpg) Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoMeta’s Instagram boss: who posted something matters more in the AI age

-

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24924653/236780_Google_AntiTrust_Trial_Custom_Art_CVirginia__0003_1.png)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24924653/236780_Google_AntiTrust_Trial_Custom_Art_CVirginia__0003_1.png) Technology4 days ago

Technology4 days agoGoogle’s counteroffer to the government trying to break it up is unbundling Android apps

-

News1 week ago

East’s wintry mix could make travel dicey. And yes, that was a tornado in Calif.

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoNovo Nordisk shares tumble as weight-loss drug trial data disappoints

-

Politics5 days ago

Politics5 days agoIllegal immigrant sexually abused child in the U.S. after being removed from the country five times

-

Entertainment5 days ago

Entertainment5 days ago'It's a little holiday gift': Inside the Weeknd's free Santa Monica show for his biggest fans

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoTrump taps Richard Grenell as presidential envoy for special missions, Edward S. Walsh as Ireland ambassador