Entertainment

In honoring Annie Ernaux, the literature Nobel Prize gets it exactly right

On the one hand, it couldn’t be extra well timed. Annie Ernaux, the 82-year-old French author who gained the Nobel Prize for literature this morning, is probably finest recognized — in america, at any fee — for her 2000 ebook “Occurring,” which chronicles the unlawful abortion she underwent in 1963 on the age of 23 and impressed Audrey Diwan’s movie of the identical identify. The film was launched right here this previous Might, not lengthy earlier than the Supreme Courtroom upended almost half a century of federal safety for reproductive rights by hanging down Roe vs. Wade.

In that sense, it hardly appears a stretch to recommend that the Swedish Academy, which administers the Nobel and prior to now has used its choice course of to make pointed political statements — Harold Pinter’s 2005 acceptance speech, as an example, framed a devastating critique of American overseas coverage main as much as the invasion of Iraq — is doing one thing related right here.

On the similar time, and as a lot as I help that intention, the selection of Ernaux as this yr’s laureate is a victory for literature. At first, it represents an overdue recognition of an creator whose idiosyncratic brilliance has been, over the course of a virtually 50-year profession, as bracing as it’s uncommon. As I as soon as wrote in these pages, Ernaux is ruthless, which is the best reward I’ve to offer. In additional than 20 books, 15 of which have been translated into English, she has successfully deconstructed not simply the memoir as a type but in addition the very query of reminiscence and identification. “Perhaps the true goal of my life,” she observes in “Occurring,” “is for my physique, my sensations and my ideas to turn out to be writing.”

What Ernaux is getting at is the concept all of us, whether or not or not we write or learn, re-create ourselves in language, within the tales by which we search to form our lives. The truth that these tales are conditional, subjective, sits on the heart of Ernaux’s work. She is just not serious about taking narrative at face worth or utilizing it to blur or soften; there may be not a sentimental sentence in her oeuvre. Reasonably, she resists the concept reminiscence could be consoling — and even contained. “My mom died on Monday 7 April within the previous individuals’s dwelling hooked up to the hospital at Pontoise, the place I had put in her two years beforehand,” she begins her 1987 memory “A Lady’s Story,” which echoes Albert Camus’ opening sentence in “The Stranger”: “Mom died at the moment. Or possibly yesterday, I don’t know.”

I take advantage of the phrase memory somewhat than memoir for a motive; Ernaux additionally resists the simplification of type. Memoir comes with a set of baked-in expectations: that it’s going to arc not directly, or construct to decision, which is the very last thing the creator has in thoughts. She is aware of, as each a human and a author, that epiphany is a fiction, that writing at its finest features as excavation, confrontation — not least with all the things we can’t rise above. Such an intention emerges in her first ebook, “Cleaned Out” (1974), which calls itself a novel even because it represents an early exploration of the fabric to which she would return in “Occurring.”

Books of Annie Ernaux on show in a library window in Paris. The 82-year-old was cited for “the braveness and medical acuity with which she uncovers the roots, estrangements and collective restraints of private reminiscence,” the Nobel committee mentioned.

(Michel Euler / Related Press)

All these recollections, all these experiences, swirl round one another in her creativeness. “Hint all of it again,” she writes in “Cleaned Out,” “name all of it up, match all of it collectively, an meeting line, one factor after one other. Clarify why I’m shut up right here in a crummy dorm room, fearful of dying and of what’s going to occur. Determine it out, resolve all of it between contractions. Discover out the place the entire mess started.” Life writing — in different phrases, autofiction — name it what you’ll.

Ernaux is just not the primary autofictionalist to win a Nobel. That might be Patrick Modiano, one other French author whose slim, impressionistic narratives hint a line between reminiscence and place. But when Ernaux’s work recollects his in some sense, what distinguishes her writing is its abiding air of complicity. In a world the place reminiscence itself is conditional, how do we all know something? How do we all know who we’re? Ernaux’s books exist within the house opened up by these questions, framing narrative as inquiry somewhat than an announcement of any sort.

Each “A Lady’s Story” and its companion quantity “A Man’s Place” (1983) characterize instances in level. On one stage, every is concerning the dying of a mother or father. On one other, they’re idiosyncratic explorations of grief. “A Man’s Place” consists looking back, reflective if not precisely backward-looking. “It’s taken me a very long time to put in writing,” Ernaux admits. (Her father died in 1967.) “By selecting to reveal the online of his life by numerous chosen info and particulars, I really feel that I’m progressively shifting away from the determine of my father. The skeleton of the ebook takes over and concepts appear to develop of their very own accord.”

An analogous conundrum motivates “A Lady’s Story,” which in contrast to “A Man’s Place” unfolds nearly solely in actual time. One of many methods Ernaux develops this ebook is to circle again, greater than as soon as, to the opening sentence, utilizing it as a form of echo that punctuates the narrative. “Tomorrow, will probably be three weeks because the funeral,” she writes at one level. “It was solely the day earlier than yesterday that I overcame the concern of writing ‘My mom died’ on a clean sheet of paper, not as the primary line of a letter however because the opening of a ebook.”

Such a transfer highlights not solely the immediacy of writing as an act but in addition the feelings Ernaux can’t resolve. “I shall by no means hear the sound of her voice once more,” she writes within the closing paragraph of “A Lady’s Story.” “It was her voice, collectively together with her phrases, her arms, and her means of shifting and laughing which linked the girl I’m to the kid I as soon as was. The final bond between me and the world I come from has been severed.” It’s, I believe, the one method to finish the ebook, with such an unrelenting phrase.

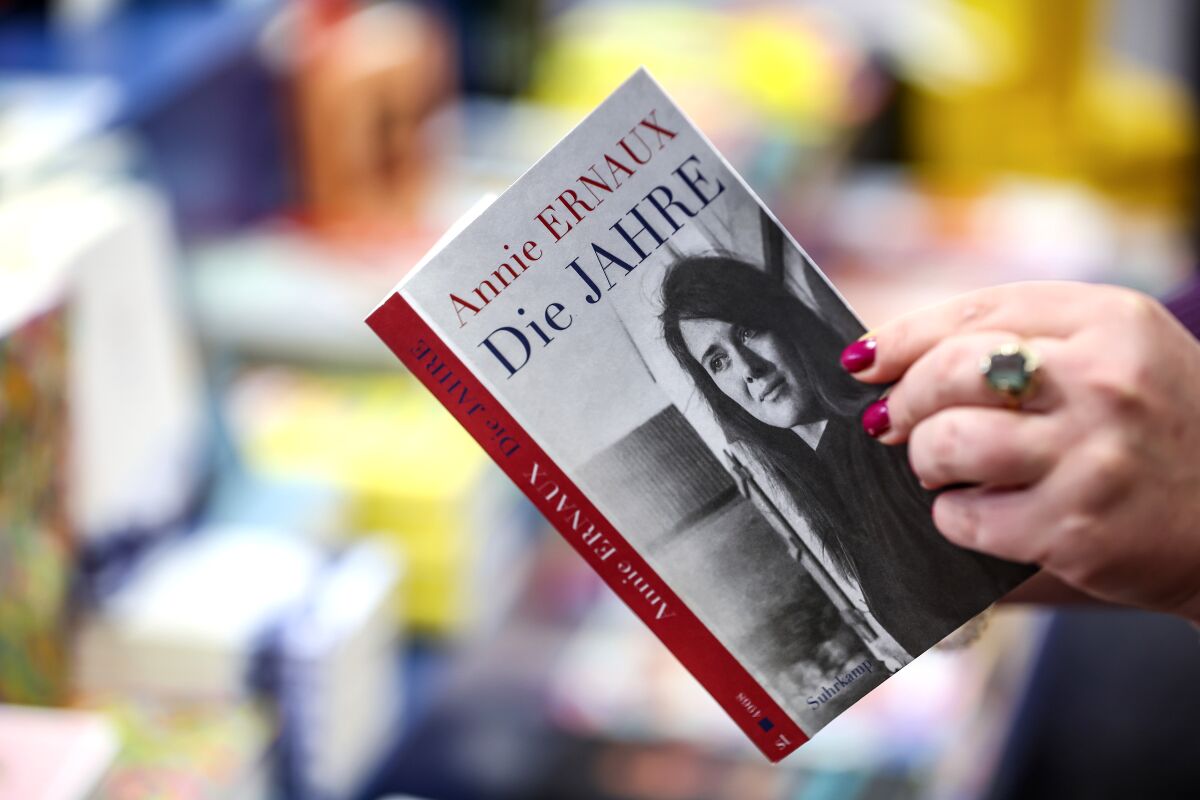

A lady opens “The Years” by Annie Ernaux in a bookstore in Leipzig, Germany. That memoir’s avoidance of the first-person “adjustments the sport,” David Ulin writes, in an acceptable capstone to her profession.

(Jan Woitas / Related Press)

Nonetheless, even because the creator has been severed, her historical past — her reminiscence — lingers. What to do about that? In “The Years” (2008), Ernaux addresses the problem head on, looking for out “a language nobody is aware of.” The answer she enacts explodes our preconceptions of voice and individual, sliding between the singular and plural, utilizing pronouns similar to “we” and “she” whereas eschewing the memoir’s defining posture: “I.”

Do I must say how thrilling that is? How this adjustments the sport? By ceding the “I,” Ernaux successfully additionally cedes her personal centrality, writing towards a perspective that’s extra collaborative — or, at the least, extra shared. A refrain by which particular person expertise turns into rendered as collective, and we’re all implicated for good and ailing.

That’s what makes her choice as laureate so exhilarating. It feels (I don’t know fairly how else to say it) like an existential win. “No lyrical reminiscences, no triumphant shows of irony,” she insists in “A Man’s Place.” Simplicity of expression and readability of voice. That’s the supply of her genius, alongside together with her unwillingness to take something with no consideration, to let herself or anybody off the hook.

“This won’t be a piece of remembrance within the common sense,” Ernaux reminds us in “The Years.” “It will likely be a slippery narrative composed in an unremitting steady tense.” She might as properly be describing her entire physique of labor.

Ulin is a former Books editor and critic for The Occasions.

Movie Reviews

Movie Review: ‘Venom: The Last Dance’ | Recent News

The last time audiences saw superpowered alien symbiote Venom (Tom Hardy) and his human “host” Eddie Brock (also Hardy) on the big screen, it wasn’t in a “Venom” movie, it was in a mid-credits sequence in 2021’s “Spider-Man: No Way Home.” The scene saw the pair briefly hop universes into the Disney-controlled Marvel Cinematic Universe, but then quickly get sucked back into the Sony-controlled Marvel universe – the one that has “Spider-Man” characters, but no Spider-Man (and is not to be confused with the animated Spider-verse). The scene is shown again at the beginning of “Venom: The Last Dance,” but it has no bearing on the story. Fans of the character should know not to expect MCU quality from this movie. This is the “Morbius”/”Madame Web” arm of the franchise.

The new film sees Eddie and Venom as fugitives in Mexico following some frowned-upon crimefighting in 2021’s “Let There Be Carnage.” They try to flee to New York, where they should be safe from human authorities, but they fail to factor in threats from non-humans. Venom’s recent activity inadvertently activated a device called a Codex, which exists as long as a symbiote and its human host are both alive. Supervillain Knull (Andy Serkis), imprisoned on a faraway planet, can use his minions called Xenophages to steal the Codex, break free and conquer the universe. I think the way it works is that if the Xenophages can swallow Venom alive, that counts as stealing the Codex for Knull. And simple evasion isn’t an option for Venom because the Xenophages are sure to cause a lot of collateral damage to Earth, and he’s the only one that can stop them. He and Eddie are going to have to fight.

If you thought I was spouting too much exposition just now, wait until you see the subplot about the secret Area 51 facility where symbiotes are studied by scientists like Dr. Teddy Payne (Juno Temple). The character comes complete with a backstory about feeling guilt over the death of her brother, who wanted to be a scientist. I get the impression that she only devotes herself to science out of guilt and not passion. If the character is supposed to be passionate about her work, it’s not coming through in Temple’s performance. She has several conversations with the facility’s enforcer Strickland (Chiwetel Ejiofor), one of those grunts that wants to kill any being he doesn’t understand, where all they do is explain the facility’s purpose to one another. Almost all of their dialogue could be preceded with the dreaded words “as you know…” because there’s no way these characters wouldn’t know all of this information already, but the audience has to be filled in.

Literally thrown off their flight, Eddie and Venom hitch a ride with the hippie Moon family, led by Martin (Rhys Ifans), on their way to Area 51 to try to see aliens. I guess the family’s scenes are supposed to be comic relief, but they aren’t funny. What is funny is a brief stop in Las Vegas where Eddie and Venom share a dance with franchise mainstay Mrs. Chen (Peggy Lu). Could the scene be cut without doing a disservice to the story? Yes. Should the scene stay in because it’s a welcome distraction from the story? Also yes.

That scene aside, “Venom: The Last Dance” is a slog. The script is a mess, the new characters unlikeable, the action murky and hard to follow, and the mindless Xenophages are terrible antagonists, with Knull not exactly helping by sitting on the sidelines the whole time. I’d say that Hardy comes off relatively unscathed because he has pretty good chemistry with… himself (I can’t decide if that makes the repartee easier or harder), but then I found out he has a story credit on this slop, so I can’t let him off the hook. I hope this really is the “Last Dance” for these “Spider-Man”-adjacent movies outside the MCU and Spider-verse.

Grade: D

“Venom: The Last Dance” is rated PG-13 for intense sequences of violence and action, bloody images and strong language. Its running time is 110 minutes.

Robert R. Garver is a graduate of the Cinema Studies program at New York University. His weekly movie reviews have been published since 2006.

Entertainment

Bare-bones ‘Streetcar’ invites a reconsideration of the Tennessee Williams’ classic

“The Streetcar Project,” a bare-bones production of Tennessee Williams’ “A Streetcar Named Desire,” passed through town last week. First stop was an airplane hangar in East L.A., followed by a warehouse in Venice.

I caught the show in Venice on Friday, after a traffic nightmare prevented me from seeing it earlier in the week in Frogtown. The production, co-created by Lucy Owen, who plays Blanche DuBois, and director Nick Westrate, employed a four-person cast. There were no props or scenery (except for a few folding chairs and some basic lighting). The costumes seemed pulled from the actors’ closets. A few sound effects (a rattling streetcar, raucous alley cats) and some period music fleshed out the surrounding world.

The focus was on Williams’ words. At times, the actors spoke their lines from obscure corners of the cavernous playing area. I found myself at times closing my eyes and listening attentively, as though to a radio drama. The production, built to be performed in alternative spaces, sought to get us to hear the play anew.

Most of the time, of course, the actors were front and center. Their appearances, with the exception of Mitch, suggested what the character might be like in a home movie. Owen’s Blanche, battered by life, looked in desperate need of a good night’s sleep. Brad Koed’s beefy Stanley seemed like he just crawled from under a broken-down car.

The plainness of Mallory Portnoy’s Stella was epitomized by the way she cuffed her jeans. The one wild card was James Russell’s “Mitch” (as Harold Mitchell is known to his friends), a leaner and less clumsy version of the character.

Russell was called upon to serve as a utility player, so perhaps it was best that he wasn’t a replica of the lumbering Mitch we’ve come to expect from Karl Malden’s memorable portrayal. Koed was no Marlon Brando, for that matter. But he was closer to the Polish American factory parts salesman than more glamorous Hollywood types striving to live up to Brando’s masculine archetype.

Few contemporary classics have been as defined as “Streetcar” by its original production. Elia Kazan, who directed the Broadway premiere and the subsequent movie adaptation, ushered in a new era of American acting with Williams’ drama

Brando, Malden and Kim Hunter, who played Stella, reprised their Broadway performances onscreen. The one significant cast change was Vivien Leigh as a replacement for Jessica Tandy in the role of Blanche. This shift was in part to alter the dramatic balance of power between Stanley and Blanche. (On Broadway, audiences were so seduced by Brando that some assumed he was meant to be the hero of “Streetcar” and not the play’s brutish antagonist.)

I appreciated the opportunity of re-experiencing the play, though I’m not convinced by this production that “Streetcar” is the everlasting masterwork it is widely assumed to be. I realize this is heresy, but I think it’s important to acknowledge the irreducible strangeness of the drama.

Lucy Owen as Blanche and Mallory Portnoy as Stella in “The Streetcar Project’s” production of “A Streetcar Named Desire.”

(Walls Trimble)

This is the story of a guilt-ridden high school English teacher, who after her role in the suicide of her gay husband, has become a sexual pariah. She was thrown out of her hotel residence for her nightly trysts and was deemed morally unfit to teach after an affair with a 17-year-old boy. Considered a nymphomaniac, a child predator and a loon, she had no choice but to seek refuge at the cramped, tatty New Orleans apartment of her sister, Stella, who wisely escaped from Belle Reve, the DuBois plantation that was lost along with the family’s last remaining connection to the Southern gentry.

Married to Stanley, a man of carnal appetites and vulgar manners, Stella has embraced the crude pleasures of realism, while her freeloading sister still clings to tattered aristocratic illusions. The standoff between Blanche’s impractical aestheticism and Stanley’s ruthless pragmatism is the heart of this quintessentially American drama. Westrate, however, is less concerned with the allegorical meaning of this battle than with the interpersonal dynamics of the combatants.

The production was determined to make the dramatic situation and characters credible for a 21st century audience. But in doing so, the play can’t help revealing its age.

Williams was writing in an idiom that was unique to him. The more stylized approaches of traditional “Streetcar” revivals aren’t just frippery. Williams challenges directors to meet his poetry without losing sight of the play’s earthiness. The characters must be larger than life and one of us.

Although the scenes are often played to music, Westrate’s staging lacks a certain lyricism. When more theatrical elements come into play — such as the Mexican flower lady crying, “Flores para los Muertos” — the staging feels almost intruded upon by an extraneous sensibility. The humor, an integral part of the playwright’s flamboyant arsenal, is also missed. In the final scene, the mix of secondary voices, pinballing among cast members, makes for a confusing pileup.

The lack of sentimentality was admirable. Owen’s bedraggled Blanche, too exhausted to keep up with her own lies, seemed complicit in her own demise. Koed’s Stanley, full of class grievance, had a vengeful look from the outset. Portnoy’s Stella clearly loved Blanche but didn’t seem to like her all that much. Russell’s Mitch was as in touch with his animal needs as with his guilty concern for his sick mother.

The true compensation of this “Streetcar” was the way the language was translated by the actors into natural-sounding speech. Each performer made the dialogue ring true to contemporary mores. The resulting authenticity passed the verisimilitude test with flying colors. But Williams, like Blanche, wants magic, not the realism of today’s TV drama.

“Streetcar” may be Williams’ most exciting and even hypnotic play, but I’m not sure it’s his best. (I prefer “The Glass Menagerie.” Theater critic Gordon Rogoff once made the astute observation that Williams was always better at writing scenes than constructing seamless dramas and that his true gift may have been as “a pointillist painter of shimmering portraits.”

That’s enough genius for any writer, but Williams goes further by offering actors the opportunity of incarnating his interior poetry. He also gives directors the chance to prove that the theater can simultaneously capture the sweaty and symbolic levels of our lives.

The production’s simplicity ditched the cliches that have accumulated around the play over decades. But it also reminded us that naturalism is only one thread in the multi-hued fabric of Williams’ playwriting.

Movie Reviews

Trap movie review (2024) –

Trap is an unconventional effort from director/writer M. Night Shyamalan. He leans into the expectations in building a captivating suspense film with a mostly satisfying finale.

Shyamalan gets unfairly dinged by critics who impatiently wait for his film’s twists and then get upset when it doesn’t deliver. For Trap, Shyamalan relies far less on a movie-altering twist. Instead, the focus is on the relentless quest to track down a serial killer.

Cooper (a terrific Josh Hartnett) is vying for Father of the Year honors. He’s scored floor seats so his daughter, Riley (Ariel Donoghue) can fangirl out over the Lady Raven (Saleka Shyamalan) concert.

While it’d be an easy layup to scream “nepotism!” to the heavens over Shyamalan casting his daughter as the pop starlet, it’s irrelevant. Saleka Shyamalan can sing and has a genuine pop star presence on the concert stage. And it’s not like he’s asking her to give some Oscar-winning dramatic performance. She just needs to play a pop superstar, which doesn’t feel like that big a stretch given her talent.

With its concert setting, the music is an integral part of Trap and Saleka Shyamalan is a major contributor as she wrote and performed 14 of the songs. The songs were catchy enough to warrant checking out the soundtrack (now available on Amazon).

Cooper quickly notices an unusually high concentration of police and armed security manning the entrances. He’s no fool and deduces they’re on to him. In a smart storytelling choice, Shyamalan doesn’t drag out the big reveal until the end — Cooper is indeed the serial killer the police are on hand to apprehend. The only catch is they’ve got no clue what he looks like just that he’s in attendance at the Lady Raven concert.

Hartnett’s performance is amazing. There are clearly different sides of Cooper at play from the trying too hard to be sweet and kind father making sure Riley has a great time and the calculating mastermind trying to escape this carefully constructed trap. Hartnett is in complete control of both aspects of Cooper’s personality in one of his strongest performances.

Donoghue is also enjoyable as the daughter who is actually appreciative of her father instead of hoping he’ll leave her alone. It makes the inevitable fallout that much more meaningful as the bond between father and daughter is well-earned.

Cooper keeps thinking ahead and avoiding the well-thought-out strategies of the profiler (Hayley Mills) on hand to aid the FBI and police making for some very suspenseful moments. It’s a little weird in the sense how Shyamalan wants the viewer engaged and marveling at Cooper’s strategy all while realizing there’s no good way to root for a serial killer.

MORE:

There are some moments that feel like Shyamalan got a little too cute in ignoring basic logic in favor of a more dramatic moment. Some of the concert crowd shots feel too intimate in a way that suggests most of the crowd were filled in via CGI.

The actual concert shots are well staged as Shyamalan places more emphasis on the singing and dancing via the large monitors rather than the stage. This provides more of a feeling of watching a concert onsite as opposed to watching a movie with a concert playing out.

Given the 1 hour and 45-minute run time, it would have been nice for Shyamalan to offer more insight into Cooper’s motives. Yes, Shyamalan provides a cursory rationale of Cooper feeling a monster is inside him and some basic mommy issues, but Trap would have played out stronger with an actual explanation beyond “he’s crazy.”

At the midway point, Shyamalan seems to have that elusive motive lined up in his sights when Cooper mentions that Riley battled leukemia. Cooper’s murder spree being the result of him getting some measure of revenge on the doctors, hospital staff and insurance agents that let Riley suffer could have provided Trap with a more complicated narrative.

As seemingly is his norm, the third act starts to get away from Shyamalan a bit. Fortunately, he can lean heavily on Hartnett to get it back on track. Trap has some problems, but it’s a fun suspense thriller that kept me engaged right through to the credits.

Rating: 8 out of 10

Photo Credit: Warner Bros.

As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases.

-

Sports1 week ago

Sports1 week agoFreddie Freeman's walk-off grand slam gives Dodgers Game 1 World Series win vs. Yankees

-

News1 week ago

Sikh separatist, targeted once for assassination, says India still trying to kill him

-

Culture1 week ago

Culture1 week agoFreddie Freeman wallops his way into World Series history with walk-off slam that’ll float forever

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoWhen a Facebook friend request turns into a hacker’s trap

-

Business3 days ago

Carol Lombardini, studio negotiator during Hollywood strikes, to step down

-

Health4 days ago

Health4 days agoJust Walking Can Help You Lose Weight: Try These Simple Fat-Burning Tips!

-

Business2 days ago

Hall of Fame won't get Freddie Freeman's grand slam ball, but Dodgers donate World Series memorabilia

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoWill Newsom's expanded tax credit program save California's film industry?