Entertainment

How the Nury Martinez scandal strikes at the heart of Latino identity

Scanning all of the media protection of the leaked Metropolis Council audio — which at this second appears poised to affix Nixon’s Watergate tapes within the annals of recording infamy — it’s laborious to resolve which sections may be essentially the most appalling. Council Member Mike Bonin, who’s homosexual, is dubbed a “little bitch.” The conduct of his adopted Black son is likened to that of a monkey. Jabs are exchanged concerning the little one, with Metropolis Council President Nury Martinez cattily describing him as “an adjunct.”

The dialog is grotesque — a furnace blast of racist tropes and unvarnished political sausage-making. It additionally surfaces a roiling debate concerning the nature of Latino identification and the blinkered ways in which identification has traditionally been outlined and wielded.

At one level within the recording, Martinez says of L.A. County Dist. Atty. George Gascón: “F— that man. … He’s with the Blacks.” The sentiment is echoed by Council Member Kevin de León, who describes Bonin because the council’s “fourth Black member,” somebody who “received’t f—cking ever say peep about Latinos.”

Elsewhere within the audio, Indigenous immigrants from Oaxaca additionally come up — actually — for denigration. Martinez describes them as “little quick darkish folks” earlier than dismissing them as “tan feos” — very ugly.

Martinez resigned from the Metropolis Council on Wednesday. The 2 different council members caught on tape, De León and Gil Cedillo, have been topic to a rising refrain of calls for his or her resignations — together with from the president of america. However regardless of the destiny of the varied events concerned (Ron Herrera, of the Los Angeles County Federation of Labor, has additionally resigned), the feedback reveal the insidious methods during which Latin America’s Black and Indigenous populations have been marginalized, their experiences overwritten by a obscure pan-continental identification. It additionally marks an outdated mind-set — a part of deeply embedded systemic points with which we’ve but to totally reckon.

For one, the us-versus-them framing of Black and Latino political pursuits actively overlooks — erases — the truth that Latinos may be Black and Black folks may be Latino. (Latino is a unfastened ethnicity, not a race, and the African diaspora spans the Americas.)

Roughly 1.2 million Latinos in america establish racially as Black, in accordance with an evaluation of census information printed final month by the Pew Analysis Heart. In Los Angeles County, in accordance with 2021 census estimates, Black Latinos quantity greater than 23,000 out of a complete Latino inhabitants of 4.8 million. That’s small in comparison with New York Metropolis, the place Afro Latinos, largely from the Caribbean, account for greater than 113,000 out of the town’s 2.5 million Latinos. However neither determine consists of blended race statistics, which probably make Afro Latino illustration greater in each areas.

If the Afro Latino presence in Los Angeles is small, it’s nonetheless one with deep roots. Afro mestizos from Mexico helped set up the town of Los Angeles within the 18th century. Extra not too long ago, the Afro Latino presence is seen culturally within the works of hip-hop artists corresponding to Kemo the Blaxican, whose songs interact the hybrid African American and Chicano expertise in L.A., in addition to author and photographer Walter Thompson-Hernández, whose Instagram account, Blaxicans of L.A., started exploring the intersections of Black and Mexican tradition half a dozen years in the past. In 2020 and 2021, La Plaza de Cultura y Artes in downtown L.A. staged a long-term exhibition titled “afroLAtinidad: mi casa, my metropolis,” which Thompson-Hernández helped set up. (The present’s affect, sadly, was blunted by the pandemic.)

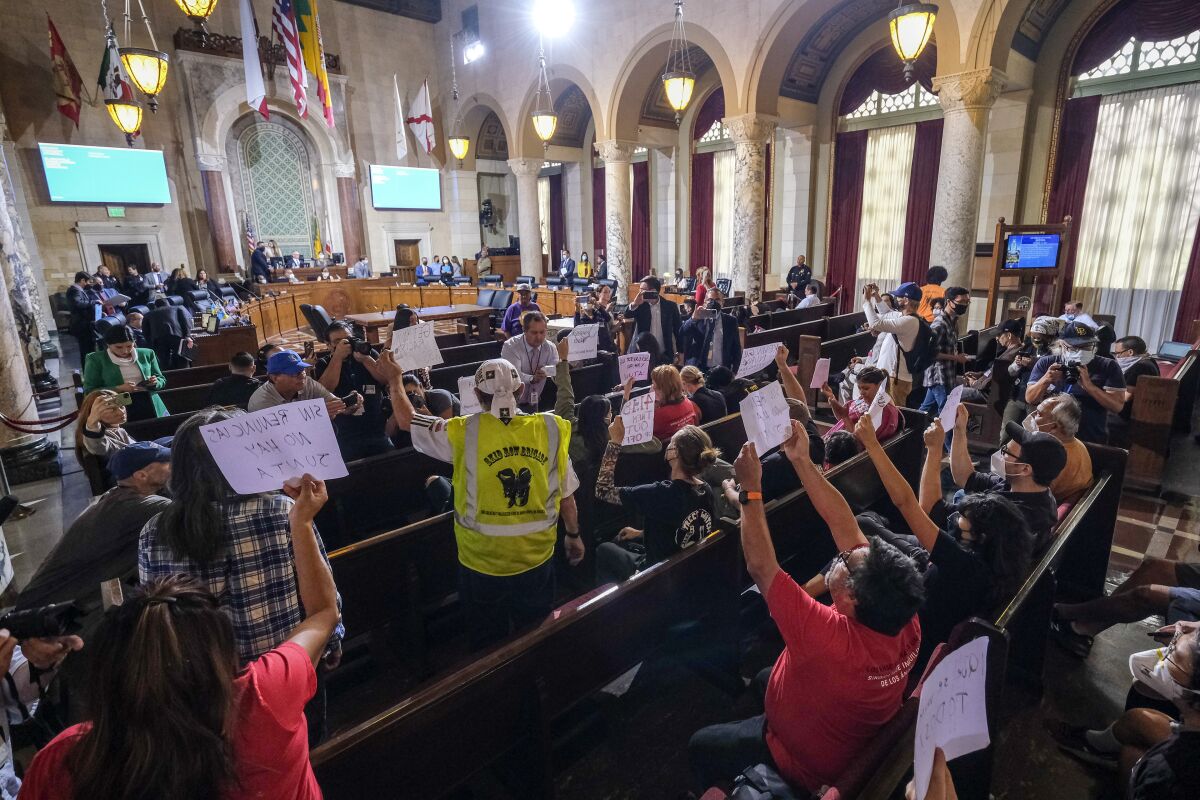

Councilmen Gil Cedillo and Kevin de León’s chairs sit empty at Wednesday’s metropolis council assembly.

(Christina Home / Los Angeles Occasions)

The erasure of Blackness inside Latino identification lengthy preceded Martinez. It’s a part of a long-running custom in Latin America.

In america, “Latino” has typically come to be equated with the obscure adjective of “brown.” In Latin America, Latino identification — Latinidad — is ceaselessly incarnated by the image of the mestizo, interpreted to be an individual of blended European (typically Spanish) and Indigenous descent. Within the essentialized type, the mestizo is somebody who’s of blended race however adopts the tradition and language of Europe. Brown — however not too brown. (In Latin America, problems with race are inclined to manifest in gradations of shade reasonably than the Black/white binary that operates within the U.S.)

Rutgers College scholar Tatiana Flores goes deep on the roots of Latinidad in an essay that appeared final 12 months in Latin American and Latinx Visible Tradition, a journal printed by the College of California Press. As she writes: “mestizaje is a venture that promotes the erasure of cultural variations within the service of the formation of a gaggle identification.” Her work tracks the methods nineteenth century intellectuals sought to create a unifying identification that marginalized Indigenous ethnicities whereas pushing Black folks utterly off the web page.

Standing, consequently, has typically been conferred to these with the best proximity to whiteness. (It’s a system that advantages a fair-skinned mestiza like myself.) In Latin America, the time period “mejorar la raza” — enhance the race — means to make it whiter. The derogatory feedback that Martinez, the fair-skinned daughter of Latino immigrants, leveled at different Latino immigrants — Indigenous Oaxacans — didn’t come out of nowhere.

It’s additionally a mind-set that belongs more and more prior to now. The leaked tapes land at a second when a youthful technology of thinkers is difficult the very foundations of Latinidad.

In 2018, a well-liked meme created by Afro-indigenous poet and theorist Alan Pelaez Lopez critiqued the affect of white supremacy on Latinidad. The hashtag Lopez positioned on the picture — #LatinidadIsCancelled — went viral consequently. Within the years that adopted, that idea has appeared in media retailers corresponding to Remezcla and on the Root, the place contributor Felicia León examined why some millennials had been rejecting the label wholesale, preferring to establish in different methods. Some Black artists, for instance, have begun figuring out as a part of Afro Latino diasporas as an alternative of assuming nationwide or ethnic labels.

The uprisings for Black lives throughout the summer time of 2020 positioned Latinidad below additional scrutiny, placing the vagaries of Latino racial hierarchies within the highlight. When Lin-Manuel Miranda’s musical function movie “Within the Heights” debuted the next summer time, it confronted controversy over its lack of dark-skinned Afro Latino illustration within the lead roles — an oversight for which Miranda later apologized.

These complicated problems with identification had been additionally on the coronary heart of El Museo del Barrio’s 2020-21 triennial exhibition, “Estamos Bien,” in New York — which I wrote about at size for the New York Overview of Books. That present embraced the fractures in Latino identification as an alternative of attempting to paper them over with some imagined idea of unity.

Protesters maintain indicators and shout slogans earlier than the Los Angeles Metropolis Council assembly on Wednesday.

(Ringo H.W. Chiu / Related Press)

It’s too early to inform what the Metropolis Corridor scandal means for Latinidad as an idea. It’s heartening, nevertheless, to see folks of all races protesting the racist vulgarities.

On Wednesday, when Martinez resigned from her submit, her mystifying resignation letter — a non-apology apology taken to epic proportions — closed with the road: “To all little Latina women throughout this metropolis — I hope I’ve impressed you to dream past that which you’ll see.” Martinez actually impressed one thing — primarily, tweets like, “Lady WHAT?”

These little Latina women? Lots of them are Black and Indigenous. An apology, maybe, would have been extra inspiring. Together with a task mannequin who sees them not as adversary however as central to the story of who we’re.

Movie Reviews

Joker 2 Is So Bad It’s Almost Laughable

In 2019, a year now separated from us by enough catastrophic global events to feel like a remote archaeological era, the movie Joker, like it or not (I certainly didn’t), was a big deal. It won the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival and later garnered a leading 11 Oscar nominations, including Best Picture, with star Joaquin Phoenix eventually winning Best Actor for his performance as a mentally ill would-be stand-up comic turned murderous clown. The movie also became the subject of heated discussion and not a little hand-wringing. Would its portrait of the comic-book villain as the lonely, misunderstood victim of mistreatment by a vaguely defined “society” inspire copycat acts of mayhem? Joker may have teetered uneasily in the balance between critiquing incel violence and being a commercial for it, but thankfully its many admirers kept their enthusiasm contained to the box office, where the film raked in over a billion dollars worldwide, shattering the all-time record for an R-rated movie.

Five years later, Joker’s director and co-writer Todd Phillips has returned with a sequel that swerves in an unseen—and on paper, intriguing—new direction: Our miserable antihero has become, of all things, the singing, dancing protagonist in his own private musical. A lot of things could be said about Phillips’ execution of that idea, most of them deservedly negative. By any reasonable measure this is a terrible movie, too long and too self-serious and way too dramatically inert, a regrettable waste of its lead actors’ boundless commitment to even their most thinly written roles. But no one could accuse Joker: Folie à Deux of being a mere cash grab, lazily recycling its predecessor’s mood, themes, or plot structure.

There’s an admirable boldness to Phillips’ decision to cast a pop supernova like Lady Gaga opposite the darkly charismatic Phoenix, then ask them both to sing, live-to-film, a jukebox-musical soundtrack of more than a dozen well-known songs that range from 1940s Broadway standards (“Bewitched, Bothered and Bewildered,” from Pal Joey) to 1970s easy-listening pop (the Carpenters’ “Close to You”). Granted, the director fails to clear the bar he sets for himself—fails hard enough, at times, to scrape the skin off his legs from knee to ankle—but it’s fair to say that this movie’s problems have little if anything to do with the attempted magic trick of its premise. It’s mainly the weirdness of that trick, and the stars’ doomed dedication to pulling it off, that renders Joker: Folie à Deux even minimally watchable.

Joker ended with Phoenix’s Arthur Fleck locked up in a mental institution but seemingly on the verge of escaping to start his career as Batman’s archnemesis. Instead, Folie à Deux finds Arthur still locked up in Gotham City’s inhumane Arkham State Hospital. Having been judged competent in a sanity hearing, Arthur is about to go on trial for the murders of five people, one of them on live television. (As he confesses to more people than he probably should, the number is really six if you include his mother.) Outside the institution’s grimy walls, he has become a folk hero to a certain set of clown-mask-sporting nihilists and a tabloid bogeyman to the public at large. But inside the hospital, Arthur remains a pitiable loser, mocked by his fellow inmates and singled out for alternately friendly and cruel treatment by an Irish prison guard (Brendan Gleeson).

Phillips’ desire to mess with the audience’s genre expectations is evident from the jump. The first thing the audience sees, after a vintage WB logo, is a cartoon short entitled “Me and My Shadow,” animated by the Triplets of Belleville filmmaker Sylvain Chomet in a style reminiscent of classic Looney Tunes. In it, Arthur’s shadow self emerges from his body to commit crimes that the real man is then blamed for. The plot of the cartoon is a literalization of the defense that his sympathetic lawyer (Catherine Keener) will later use in court: Arthur, she believes, is the victim of dissociative identity disorder, a former abused child who’s made up the Joker character as a way to vent his otherwise inaccessible rage. It’s not clear whether the movie wants us to agree with her assessment or with that of Gotham assistant district attorney Harvey Dent (Industry’s Harry Lawtey), who thinks Arthur is merely a sociopath faking mental illness in order to escape the consequences he deserves.

Meanwhile, Lee Quinzel (Gaga), an arsonist serving time in Arkham’s minimum-security wing, has a very different vision of the Joker: She’s a groupie, having followed his crime spree in the news and obsessively rewatched a TV biopic about him. (Even fans who haven’t consumed the aggressive marketing won’t take long to recognize her as the future Harley Quinn.) When they’re put in the same music-therapy group—a place where cheery sing-alongs are touted as a wholesome counterpoint to the grimness of asylum life—Lee and Arthur bond instantly and soon develop their own more twisted motives for bursting into song. When they’re together, or apart and thinking of each other, their internal monologues bubble to the surface as ready-made classics of the American songbook. This despite the fact that Lee, for her part, seems not to be a big fan of the musical genre. When the asylum shows the MGM classic The Band Wagon on movie night, Lee gets so bored she sets fire to the rec-room piano. Not liking The Band Wagon should surely serve as a red flag for any prospective suitor, but Lee redeems her taste later on, when the by-then-besotted couple belts out a cover of that musical’s most enduring number, “That’s Entertainment.”

Joker: Folie à Deux is hardly the first musical to posit the idea of its song-and-dance sequences as the emanations of a delusional mind, but it must be among the ones that hammer hardest on that conceit. In scene after scene, often with hardly a break for dialogue in between, either Lee, Arthur, or both in unison will channel the intensity of an emotional moment by delivering a breathy version of some beloved pop hit or other. Invisible string orchestras may swoop in to accompany these flights of fancy, just as they would in a Hollywood musical, but the secondary characters never join in and seldom seem to notice that a serenade is taking place. With rare exceptions (like the rock-’em-sock-’em Gaga cover of “That’s Life” that plays under the closing credits), most of the vocal performances in Folie à Deux are purposely underwhelming in terms of virtuosity: They’re husky, scratchy, and in Phoenix’s case often half-spoken, suited more for a tipsy karaoke night than for the Broadway stage.

Gaga has pointed out in interviews that neither her nor Phoenix’s character is a professional entertainer, so why should they sing like one? It’s a reasonable point, as is a less polite one she doesn’t make: that if she sang full-out instead of curbing her usual vocal splendor, the contrast would place Phoenix’s adequate but limited baritone in unflattering relief. But what makes the songs, irresistible toe-tappers all, start to blur into a drab wall of sound has less to do with the performance quality than with the nonstop onslaught of musical numbers and the sluggishness of the story in between. Other than the building of internal emotion to the point that it must express itself in song—over and over and over—precious little happens in Folie à Deux. Arthur is declared fit to stand trial, goes to court, and is marched back by the cruel guards each night to the bleakness of his cell. A few familiar characters from the first Joker, including Zazie Beetz as Arthur’s former neighbor, show up to take the stand, and at one point a horrific act of violence interrupts the proceedings. But the forward motion of the story is so minimal, and so broken up by long stretches of musical stasis, that the result barely feels like a movie. It’s more like a work of Joker fanfic, created not just by the credited screenwriters (Phillips and Scott Silver, who also co-wrote the 2019 film) but by Phoenix and Gaga themselves in what was apparently a collaborative project to revise the script in real time during the shoot.

The fact that Folie à Deux has the self-referential quality of fanfic does not necessarily mean it will go down well with actual Joker fans, who seem likely to come out scratching their heads over a sequel about a comic-book supervillain that contains virtually no fight scenes, a single car chase that ends roughly a minute after it begins, and scarcely a moment that could be classified as suspenseful. The main question to be answered by the viewer is not “What will happen next?” but “Is all this taking place in the real world, or just inside their heads?”—an epistemological puzzle that is not enough in itself to sustain our energy for nearly two hours and 20 minutes. Even more confoundingly, all this time spent locked in the psyches of two deeply disturbed characters gives us little insight into their motivations. The pathetic Arthur Fleck remains, as I called him in my review of the 2019 movie, a “poor little clownsie-wownsie,” while Gaga’s Lee is so underwritten we remain unsure to the end whether she is a vulnerable fangirl or a heartless femme fatale. If he is, as the lyric from “That’s Entertainment” goes, “the clown with his pants falling down,” does that make her simply “the skirt who is doing him dirt”? To make Gaga’s character little more than a mirror that reflects the Joker back to himself (in alternately flattering and unflattering ways) is a real squandering of this powerhouse performer, whose life experience as a stadium-filling superstar has given her no shortage of insight into the psychology of fame monsters.

Without spoiling the ending, it’s safe to say that with it, Phillips seems to foreclose the likelihood that anyone will be begging for more. That’s probably a blessing for both the filmmaker and us, since this somber, muddled, maudlin film seems to have been made by someone who holds his characters and his audience in contempt.

Entertainment

Review: Nickel Creek awes and amazes at the tiny Largo theater

Nickel Creek played an intimate warmup show at Largo at the Coronet for a lucky crowd Wednesday that piled into the L.A. theater for a night of skillful, spellbinding folk music.

At first, it seemed impossible: How could such a good band play such a small venue? At 280 seats, the Largo is much smaller than the high school auditorium that was regularly subjected to my bands’ takes on jazz, reggae and the like.

The group is touring with Kacey Musgraves, so this show was jammed between a show in San Diego and two at the Forum in Inglewood. They sandwiched songs from their new album, “Celebrants,” between recognizable hits, exposing the crowd of about 250 people to new material while still delivering plenty of nostalgia from past releases.

With all four members of the band sharing one microphone, they opened with a few crowd favorites, including “Smoothie Song,” one of the most technical instrumental pieces any folk band will ever play.

Nickel Creek’s songs have a theatrical quality to them — many tell a story, and a few are quite funny. I’d never noticed the comedy in the lyrics on tape, likely because the band’ recordings always grip me instantly with the audacity of the instruments they feature. For example, “To the Airport,” a song about flying, was genuinely funny and musically complex. It’s a high-wire act that few, if any, other artists can pull off. If Weird Al had gone to Berklee and met three other Weird Als, this song might have been the result.

“Thinnest Wall” was probably the biggest hit from “Celebrants,” released in 2023.

After playing the album from front to back, the band took audience requests. And I mean really took them. To summon such challenging and intricate music at the drop of a hat is another of the band’s magic tricks. This included a rousing cover of Britney Spears’ “Toxic,” which was probably the musical low point of the night. Though the cover was spotless and the crowd loved it, using a few precious moments of Nickel Creek’s time to do something simple felt like a waste. The song simply isn’t complicated enough for the band to flex its abilities.

There are some concerts where the technical proficiency on display melts my face early on. This was one of those nights, assuming a place in the chops pantheon alongside acts like Thundercat and Anderson Paak.

In these cases, my awe is generally reserved for one or two members of the band. However, Nickel Creek consists of four truly exceptional musicians, and three of them are singing complex harmonies while shredding on mandolin, violin and guitar, respectively. Altogether, it was the most dazzling display of musical talent I’ve ever seen.

As for the crowd, no one sang along, and any clapping was done mostly between songs, as everyone focused on hearing the exquisitely intricate strumming. The venue forbids phones, so it was a joy to see a crowd focused on the stage without hundreds of little screens recording poor facsimiles of the live event.

Nickel Creek is really a live band first and foremost. Though I’ve loved its albums for decades now, any recording implies the use of production tricks and multiple tracks to make the sound possible. So I was unprepared for the idea that their studio albums actually could have been recorded live. The execution on stage left me in awe, willing to believe pretty much anything.

Writing this review was difficult because I would prefer to keep the secret to myself: The best live band available in L.A. plays a tiny venue once in a while. Next time they do, we may be competing for limited seats. I can only hope they keep doing it, for music’s sake.

Movie Reviews

Without Gore or Violence, This Serial-Killer Thriller Creeps Into Your Soul

Laurie Babin and Juliette Gariépy in Red Rooms.

Photo: Nemesis Films

There are no real red rooms in Canadian director Pascal Plante’s unnerving thriller Red Rooms. Mostly a lot of white, gray, blank ones — from the bare and futuristically antiseptic courtroom where a grisly trial is taking place, to the minimalist high-rise Montreal apartment where the film’s protagonist lives, to the squash courts where she takes out her anger. The title refers to the horrific, blood-soaked dungeons where, it is alleged, the serial killer on trial — Ludovic Chevalier, also known as “the Demon of Rosemont” and played wordlessly by Maxwell McCabe-Lokos with saucer-eyed, predatory calm — mutilated his teenage victims while livestreaming the slaughter for money. We do witness distant flashes of such a room at one point, but the idea mostly looms over the film like an unseen dimension, a psychotic alternate reality beneath and beyond the eerie, empty drabness of modern life.

Plante’s interest lies not so much in the criminal or his victims but on the people obsessed with him. The film (which is now available on demand and playing in select theaters) follows Kelly-Anne (Juliette Gariépy), a statuesque and mostly expressionless professional model who gets in line early every night to get into the small courtroom in the morning. Deep into the world of the dark web, Kelly-Anne spends much of her time playing online poker with Bitcoin and hacking into other people’s private lives — even accessing the email accounts and security codes for the grieving parents of the Demon’s victims. Kelly-Anne doesn’t show much emotion, but Plante often accompanies her scenes with wailing, operatic music that is as expressive as she is not. She also meets another serial killer groupie who could be her polar opposite in personality, Clémentine (Laurie Babin), a manic chatterbox who genuinely believes Chevalier must be innocent because his big eyes are too kind. (His eyes, by the way, are not kind — and Plante makes fine use of them in one of the film’s more striking scenes.)

There is no real bloodshed in Red Rooms, but there is a kind of spiritual savagery. Plante achieves this partly through subtraction: Confronted with a verbal accounting of the Demon’s unspeakable crimes, Kelly-Anne’s poker-faced fascination with the trial is increasingly hard to read. Is she drawn to Chevalier and his alleged acts, or repulsed by them? This is among the many questions that hang in the air for most of Red Rooms’ running time, and the unnerving mystery of Kelly-Anne’s psyche, combined with the ease with which she moves through the shady corners of the internet, present a portrait of a very modern soul — unreadable, unstable, and unsettling.

At the same time, the initially controlled direction of the film — with its long, deliberate tracking shots, and orderly spaces — suggests a character who is herself fully in control of herself and her surroundings. Kelly-Anne might be unwell, but she’s also quite cool. This contrasts sharply with the messy behavior of Clémentine, who during one of the movie’s more bravura sequences calls into a late-night talk show to try and defend Chevalier, only to reveal how unhinged she really sounds. But as Red Rooms proceeds, Kelly-Anne’s reality also begins to slip, and the film’s style becomes looser, more frantic and fragmented. So much so that we might even start to question the veracity of what we’re seeing.

Despite the (thankful) lack of gore and violence, Red Rooms feels curiously giallo-adjacent at times. The bursts of formalism, the melodramatic score, the ways in which the model-protagonist’s own profession becomes a stylistic barometer for her mental state — these are all evocative of that classic, colorful subgenre of horror. What’s missing is the tongue-in-cheek exploitative quality of giallo. Or is it? By denying us cheap thrills, and by pointedly going in the other direction, Red Rooms highlights their absence. This picture about people obsessed with criminals and their grisly crimes confronts us with the mystery of who the obsessives truly are; the questions we ask of Kelly-Anne could also be asked of all us genre fiends. The expressionless, fascinated gaze at the heart of this film is ultimately not the protagonist’s, but our own.

See All

-

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25439572/VRG_TEC_Textless.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25439572/VRG_TEC_Textless.jpg) Technology2 days ago

Technology2 days agoCharter will offer Peacock for free with some cable subscriptions next year

-

World1 day ago

World1 day agoUkrainian stronghold Vuhledar falls to Russian offensive after two years of bombardment

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoVideo: Where Trump and Harris Stand on Democracy

-

World2 days ago

World2 days agoWikiLeaks’ Julian Assange says he pleaded ‘guilty to journalism’ in order to be freed

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoVisa, Google, JetBlue: A Guide to a New Era of Antitrust Action

-

Technology1 day ago

Technology1 day agoBeware of fraudsters posing as government officials trying to steal your cash

-

Education1 week ago

Education1 week agoVideo: Los Angeles Bus Hijacked at Gunpoint

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoFLASHBACK: VP Harris pushed for illegal immigrant to practice law in California over Obama admin's objections