Entertainment

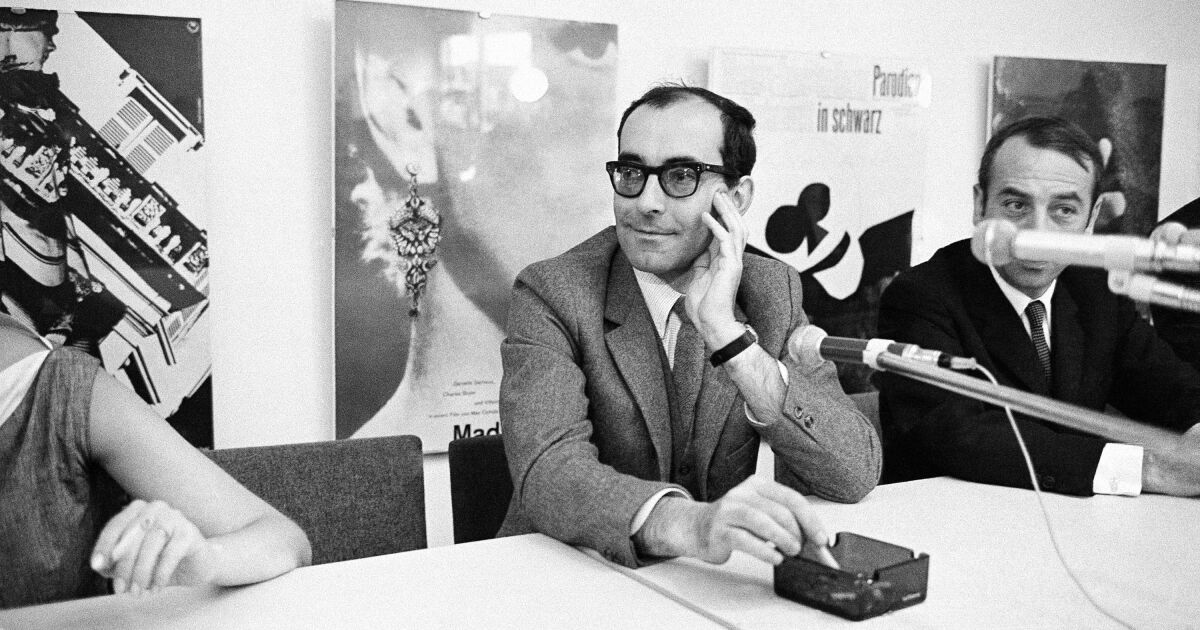

Appreciation: Jean-Luc Godard, a master of cinema who changed the medium forever

Of all of the endlessly quotable maxims and aphorisms which have poured from the mouth and the flicks of Jean-Luc Godard — “All you might want to make a film is a lady and a gun,” “The cinema is fact at 24 frames per second,” “A narrative ought to have a starting, a center and an finish, although not essentially in that order” — one which particularly springs to thoughts right this moment is that this: “He who jumps into the void owes no rationalization to those that stand and watch.”

It appears becoming to contemplate these phrases this week, and the void as nicely. Godard, filmmaker, critic, essayist, polemicist, crank, disruptor, legend and one of the vital artists working in any medium during the last century, is gone right this moment at age 91, having died by assisted suicide at his dwelling in Rolle, Switzerland. The motion-picture medium that he studied, worshiped, mastered, mocked, deconstructed and sparred with for many years feels instantly and infinitely poorer for it. Does it really feel, even, just like the “finish of cinema,” to cite the kicker of his 1967 apocalyptic freakout, “Week-end”? I hope not, but it surely’s onerous to suppose for even a second about what Godard means to cinema, an artwork kind he revolutionized like no different, and never really feel that one thing has completely shifted.

The loss is incalculable. The tributes will likely be as voluminous and scholarly as his output, and they’re going to mark not the tip of a collective remembrance however a starting. The follow of honoring our creative giants is one which thrives on evaluation, although talking as somebody who’s much less of a scholar than a lay admirer of Godard’s work, I don’t really feel notably massive on explanations myself proper now. What feels extra becoming to supply at this still-early second of reckoning is a cluster of observations, associations and protracted reminiscences from a moviegoing life that this towering artist and fearless iconoclast has lengthy enriched.

From the second he burst onto the world cinema stage, Godard operated with each a cool, insouciant defiance of cinema’s entrenched guidelines and traditions and a refusal to unpack his meanings for simple consumption. Then once more, with a primary characteristic as heady as “Breathless,” little rationalization was actually wanted. Audiences stumbling out of a theater in 1960 could not have grasped the total significance of what that they had simply seen, however the film’s playfulness and audacity swept them proper up together with it. Hurling Jean-Paul Belmondo and Jean Seberg right into a lovers-on-the-run crime plot that couldn’t have been extra inappropriate, it was comedian and tragic, dizzying and desultory, scrappy and totally fashioned, America and Paris, a jolt and a masterpiece. Above all, it was the work of a filmmaker who knew and liked the beats of classical cinema so deeply that there was nothing left to do, actually, however throw them out the window and begin contemporary.

Jean Seberg and Jean-Paul Belmondo in Jean-Luc Godard’s “Breathless.”

(Rialto Footage / StudioCanal)

Over the primary seven years of his profession, which planted him on the forefront of the French New Wave and the peak of his worldwide cine-celebrity stardom, Godard cranked out an astonishing run of 15 options. From “Breathless” to “Week-end” (1967), they continue to be nonpareil of their stylistic invention and power, their mixture of scruffy dynamism and unattainable glamour. Watching them — and so they maintain up superbly — you’ll be able to all however really feel a medium racing to maintain tempo with a culturally and politically tumultuous second that was shifting and fragmenting extra shortly than anybody, save maybe Godard, might take inventory of.

A lot of his best-loved films arose from this ’60s heyday, and so they linked and endured with audiences, partly as a result of their irreverent play with the medium was so clearly a type of love. “Breathless” and “Band of Outsiders” (1964) had been romantic gangster films in a lot the identical indirect method that “A Girl Is a Girl” (1961) was a musical or “Alphaville” (1965) was a bit of science fiction. They handled style as a beloved and well-worn toy, one thing to be performed with for slightly and finally solid apart in favor of one thing extra fascinating. In doing so, they broke proper by the seamlessness and artifice, the phantasm of coherence, that audiences had come to count on from films. Godard’s films knew they had been films and noticed no level in pretending in any other case.

Unleashing a wild panoply of movie strategies — bounce cuts, reams of textual content, eye-popping major colours (but additionally jazzy black-and-white), verbal and visible nonsequiturs, startling disjunctions between sound and picture — Godard liberated the medium from its prior allegiances to older artwork varieties like literature and theater. On the identical time, he exuded a magpie’s enjoyment of sending cinema into collision with each different area of the second. He mashed up pop and classical music and drew graphic affect from shiny advertisements and film posters. He took a pickaxe to each crucial and business assumption about what films might and ought to be, broke them huge open and reassembled the fragments into one thing radically unusual and new.

To understand his work aesthetically requires a willingness to see — or to be taught to see — the wonder in all this rupture and fragmentation, in states of confusion and typically maddening incoherence. To confront them intellectually is to wrestle with topics that vary from the pitfalls of consumerism and mass tradition, topics he critiques with magnificence and feeling in “Masculin Féminin” (1965), to the temptations and contradictions that ensnare the characters in “La Chinoise” (1967), his alternately satirical and tender portrait of younger Maoist radicals. It means contending along with his dismissals of Steven Spielberg and Hollywood in “In Reward of Love” (2001), the gorgeous and bilious work that heralded, for a lot of, a significant creative comeback, and likewise to understand his despair over anti-Arab violence and battle in each “Notre Musique” (2004) and “The Picture Ebook” (2018), his final launched characteristic.

However to overemphasize the problem of Godard — fairly aside from ignoring the truth that problem will be, in itself, one thing fairly pleasurable — is to threat understating the sheer magnificence and, at occasions, the tenderness of his work. Film lovers have lengthy enshrined the pictures of Anna Karina, Godard’s former spouse and longtime muse, racing by the Louvre along with her male mates in “Band of Outsiders,” and contemplated the multitude of meanings implicit in a cup of espresso’s swirling floor in “Two or Three Issues I Know About Her” (1967). They’ve swooned over the mad Technicolor collision of women and men, colours and types within the magnificent “Pierrot le Fou” (1965) and the moody erotic languor of Brigitte Bardot and Michel Piccoli in “Contempt” (1963), for a lot of Godard’s supreme masterpiece and most emotional work, by which he grapples with the tip of his marriage and likewise that of the Hollywood cinema he grew up loving.

The visible great thing about his work continued and even perhaps deepened nicely after his storied ’60s interval, these many years throughout which Godard remodeled from a bespectacled, cigar-wielding New Wave icon into one thing altogether more difficult for a lot of to embrace. For his most dedicated partisans, he found ever extra freewheeling and thrilling tributaries of cinematic which means with films like “First Identify: Carmen” (1983), “Détective” (1985) and “Nouvelle Obscure” (1990), alongside the best way branching out into collaborative filmmaking initiatives and embracing the probabilities of digital video. For others, these many years weren’t a interval of development however retreat, into ever extra bewildering and even punishing realms of inscrutability.

I’d hardly be the primary particular person to admit to discovering my share of late-Godard films perplexing, which isn’t to say I’ve given up on them, particularly since I’ve additionally discovered my share of them deeply pleasurable, beneficiant and typically attractive past phrases. One in every of his most rapturously obtained works of the final decade is “Goodbye to Language” (2014), a 69-minute astonishment of sight and sound that resembled a few of his earlier work in its jagged allusions, its bursts of textual content and its lovely girls — but additionally, due to its dazzling experiments with 3-D, resembled nothing he’d ever made earlier than.

“Godard perpetually,” an viewers member yelled out because the lights dimmed on “Goodbye to Language’s” first screening in Cannes (some 46 years after the 1968 version of the pageant, which he and several other different self-styled cine-revolutionaries delivered to a screeching halt). A number of months later, “Goodbye to Language” was named finest image of 2014 by the Nationwide Society of Movie Critics — a call that delighted numerous small pockets of the cinema-loving world and drew all-too-predictable accusations of pretension and elitism from some who’d barely heard of it, not to mention seen it.

Heaven is aware of Godard didn’t make movies to win prizes, not to mention break field workplace data. However it was immensely satisfying to know that this unaccountably nice and ingenious artist, then 84 and within the twilight of a profession that modified cinema and the world, was nonetheless able to ticking off all the proper folks. Lengthy could he proceed. Godard perpetually.

Movie Reviews

‘The Village Next to Paradise’ Review: Somali Family Drama Doubles as a Potent Portrait of Life in the Shadow of War

Mo Harawe’s debut feature The Village Next to Paradise is a haunting offering. The film, which premiered at Cannes in the Un Certain Regard section and is the first Somali film to ever screen on the Croisette, presents a compelling narrative of one family’s survival in a sleepy Somali town. But it’s the devastating backdrop against which their drama plays out that lingers long after the credits roll.

The siren wails of drones soundtrack each scene of Harawe’s film, which opens with footage of a real-life report of a United States drone strike on Somalia. Since the U.S. began using drones in the East African country in the early 2000s, Somalis have suffered at the hands of an enveloping and ravenous counterterrorism operation. According to data from the New America foundation, there have been more than 300 documented uses of drones resulting in hundreds of known civilian deaths.

The Village Next to Paradise

The Bottom Line Uneven but affecting.

Venue: Cannes Film Festival (Un Certain Regard)

Cast: Ahmed Ali Farah, Ahmed Mohamud Saleban, Anab Ahmed Ibrahim

Director-screenwriter: Mo Harawe

2 hours 13 minutes

The fatal impact of contemporary warfare organizes life in Paradise village, a locale whose name seems more melancholic with time. Marmargade (Ahmed Ali Farah), a principal character in Harawe’s languorous film, makes money doing odd jobs, but one of his most lucrative gigs involves burying the dead. Some of the people for whom he finds a place in the sandy terrain died of natural causes, but many of them are victims of foreign airstrikes. When this business slows, Marmargade reluctantly smuggles a truck full of goods — the contents of which play a pivotal role later — to a nearby city.

Because Marmargade knows the realities of living in a place shrouded by the shadow of death, he strives for a better life for his son Cigaal (Ahmed Mohamud Saleban), a buoyant kid who thinks nothing of the constant buzzing coming from the sky. When the local school cancels classes for the year because of chronic absenteeism among the teachers, Marmargade works to send Cigaal to a school in the city, where safety is more than an illusion. But Cigaal doesn’t want to leave his family, friends or his life in the village. When Marmargade proposes this new life to him, the child rejects the idea.

The main narrative of The Village Next to Paradise revolves around the conflicting desires within this makeshift family. Marmargade lives with his sister Araweelo (Anab Ahmed Ibrahim), a recently divorced woman who wants to build her own tailoring shop. The two have the kind of fractious relationship resulting from years of mistrust. She thinks her brother should be honest with Cigaal instead of trying to trick the young one into going to school. Marmargade wants his sister’s financial support more than her advice. After she refuses to lend him the money for tuition, Marmargade makes a series of decisions that threatens all their livelihoods.

Harawe’s film contains many admirable elements. With its unhurried pacing and tender focus on a single family, The Village Next to Paradise recalls Gabriel Martins’ 2022 feature Mars One. And the way Harawe structures the film around a broader geopolitical conflict resembles the role the Chadian civil war played in Mahamet Saleh Haroun’s 2010 film A Screaming Man, which also premiered at Cannes. The cinematography (by Mostafa El Kashef) offers truly striking images that conjure up the ghostly atmosphere of this village without turning its people into caricatures for a Western gaze hungry for a particular kind of poverty porn.

But The Village Next to Paradise is also hobbled in places by its meandering narrative and occasionally wooden performances from Harawe’s cast of local nonprofessional actors. The sharpness of Harawe’s vision is dulled by a story that takes one too many detours before settling into itself. Characters with dubious relevance are introduced and then dropped, while ones who come to play crucial roles don’t get an appropriate amount of screen time.

The film becomes more dynamic in its latter half, when Marmargade’s desperation leads him to questionable decisions that clash with Araweelo’s desires. Indeed, it’s also during these parts of the film that Harawe pulls the strongest performances from his actors, who otherwise struggle to shake off an understandable stiffness.

Despite these flaws, Harawe’s film does have a real staying power. The Village Next to Paradise orients itself around a quiet optimism and surprising humor that mirror real life. There are moments throughout that serve as a reminder that even in places where death feels close, hope for tomorrow is still alive.

Entertainment

‘Masked Singer’ winner reveals whether they will resume 'Musical' — that was a clue — career

Sixteen contestants went down to one Wednesday night when the “Masked Singer” crowned Goldfish the winner. Underneath the mask was Disney darling, Coachella queen and Broadway beauty Vanessa Hudgens, who was champion of Season 11 of the reality TV competition series.

The competition was down to Goldfish, who sang “Heart of Glass” by Blondie and “Don’t Let the Sun Go Down on Me” by Elton John, and Gumball, who chose “Latch” by Disclosure featuring Sam Smith and “Renegade” by Styx. The candy man was revealed to be “Friday Night Lights” star Scott Porter, who worked with Hudgens on 2009’s “Bandslam.”

Judges Jenny McCarthy-Wahlberg and Robin Thicke both guessed incorrectly that he was Derek Hough. Ken Jeong guessed Taran Killam, and Rita Ora thought Joseph Gordon-Levitt was under the mask.

They fared much better unmasking Goldfish: While Thicke guessed Hilary Duff and Jeong said it was Nicole Scherzinger, both Ora and McCarthy-Wahlberg were correct that the star of Broadway’s “Gigi” was their winner.

“It’s honestly the most incredible thing ever. I’ve just been so excited to take my mask off and stare into Rita’s eyes and be like ‘Girl, this is why I couldn’t hang out with you,’” Hudgens, a longtime friend of Ora’s, exclaimed after the reveal.

“I was like, ‘What’s going on with Vanessa? She always texts me back’ — but now it’s because you were here,” Ora yelled back from the judges’ seats.

The “High School Musical” star had been asked to join the show several times but decided this time to give her fans a taste of what they’ve been missing in her time away from music, Hudgens told ET.

“My fans had been asking, saying, ‘We want more music, we want singing anything, give it to us please.’ And I was like, ‘You know, this would be a really interesting way to give my fans what they want, but make sure they’re really fans,’” she said. “And they are!”

But the Queen of Coachella, so named because of her remarkable outfits at the annual Southern California music festival, admitted that she would probably stick to the screen for the immediate future.

The actor’s “Bad Boys: Ride or Die” opens in theaters on June 7. It’s the fourth film in the Will Smith-Martin Lawrence buddy cop action comedy franchise. Hudgens also co-starred in the third movie, “Bad Boys for Life.”

“I always say life is about priorities and [music’s] just not a top priority right now,” the new mom said. “Who knows? Maybe down the line, maybe it will be, but as of now, it’s still no.”

Movie Reviews

Short Film Review: Karita (2023) by Virginia de Witt and Koji Ueda

“So I came here…”

Headed by actress-turned-director Virginia de Witt and Koji Ueda, a Kyoto-born Tokyo-based director, photographer, and filmmaker, “Karita” is a film inspired by the manga series “Nana”, while trying to answer the question, what if “Lost in Translation” was cast with the “Fleabag” character. The 17-minute short will be premiering at the Dances With Films Festival on June 22nd in Los Angeles.

The film begins with a series of impressive images from nighttime Tokyo, while the ominous music suggests that something dangerous is about to happen. The next scene has two women walking in the streets during the day, as Nico, an American, is shown around Tokyo by her friend

and supervisor at a local record store, Rumi. The camera is shaky and the cuts frantic, while there is a different dialogue heard in the background. The next, dominated by neon pink lights scene, brings us to the location the dialogue is taking place, inside a bar, where the two girls are talking to two boys and one girl, with Nico asking them if they have ever done anything dangerous. One of the boys, Ren, starts talking about people stealing cars. Nico shares her own experience in the US, which makes everyone in the table rather amused.

The night continues with a lot of drinking and eventually, Rumi decides to go home, cautioning her friend not to do anything stupid, before she goes. The next scene takes place in a garage with a sports car, which belongs to the uncle of the second of the boys in the company, Kenji. Suki, the other girl, who is quite drunk, insists they take the car for a drive, despite the yakuza-like uncle having specifically cautioned his nephew otherwise. In the end, with Ren in the driver’s seat, they take a drive around Tokyo.

Unfolding much like a road-movie/music video, “Karita” will definitely stand out due to its impressive visuals, with Koi Ueda’s cinematography, in combination with the impressive lighting and coloring, capturing night time Tokyo in the most impressive fashion. Curtis Anthony Williams’s frequently frantic editing also adds to this sense, while the rather fast pace definitely suits the overall aesthetics here.

At the same time, there is a part of the movie that is quite realistic as the group visit various locations, as a pier, a convenience store, the record store, and the aftermaths of getting drunk and doing stupid things is also highlighted. A pinch of humor, as in the whole concept of the uncle and Suki’s actions, and some notions of romance, cement the rather entertaining narrative here.

Virginia de Witt plays the foreigner that tries to appear cool in order to fit in with gusto, while Haruka Hirata as Rumi is quite convincing as the “cautious” friend, with the chemistry of the two also being on a very high level, presenting a rather kawaii relationship between them. The other actress that stands out here is Mika Ushiko, who is quite convincing as the drunk Suki.

As mentioned before though, the aspect that makes “Karita” stand out is definitely its production values, which are on a level very rarely met in short films, while being the main reason the movie definitely deserves a watch. All in all, a very appealing film, in an effort that intrigues on what the filmmakers could do with a bigger budget in their hands, that would allow them to explore the script and the characters more.

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoReports of Biden White House keeping 'sensitive' Hamas intel from Israel draws outrage

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoPro-Palestinian university students in the Netherlands uphold protest

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoDem newcomer aims for history with primary win over wealthy controversial congressman

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoSouthern border migrant encounters decrease slightly but gotaways still surge under Biden

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoWhite House walks diplomatic tightrope on Israel amid contradictory messaging: 'You can't have it both ways'

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoSlovakia PM Robert Fico in ‘very serious’ condition after being shot

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoDespite state bans, abortions nationwide are up, driven by telehealth

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoCanadian Nobel-winning author Alice Munro dies aged 92