Culture

Roman Abramovich and the End of Soccer’s Oligarch Era

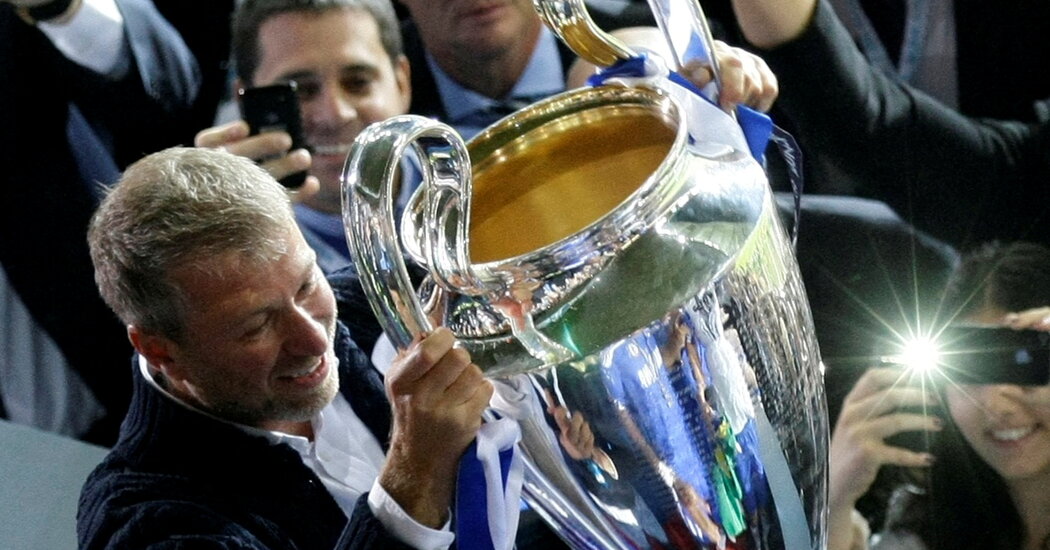

There have been, through the years, three tales that defined how Roman Abramovich washed ashore at Chelsea. Each, now, serves as a type of time capsule, a carbon-dated relic from a particular interval, capturing in amber every stage of our understanding of what, exactly, soccer has turn into.

The primary took root within the instant aftermath of Abramovich’s takeover of Chelsea. It was gentle, fuzzy, faintly romantic. Abramovich, the story went, had been at Previous Trafford on the evening in 2003 when Manchester United’s followers stood as one to applaud the good Brazilian striker Ronaldo as he swept their crew from the Champions League.

Abramovich had been so smitten, it was stated, that he had determined there after which that he wished a bit of English soccer. He thought of Arsenal and Tottenham and settled on Chelsea, drifting bohemian and glamorous slightly below the Premier League elite. He had fallen, so onerous and so quick, that he purchased the membership in little greater than a weekend.

And that, on the time, was nearly sufficient. It was absurd, alien, the thought of this unimaginably rich enigma all of a sudden descending on Chelsea, lavishing lots of of hundreds of thousands of {dollars} in switch charges as in the event that they had been nothing. But it surely was flattering, too, in these early days of Londongrad, of Moscow-on-Thames, because the stuccoed homes of the capital’s most interesting streets had been filling with Russian oligarchs, the nation’s most interesting faculties thronging with their kids.

All of it appealed not simply to the laissez-faire method of Tony Blair’s Britain — come one, come all, so long as you possibly can pay for the worth of a ticket — however to the ego of each the nation as an entire and the Premier League specifically.

Russia’s younger plutocrats had extra money than Croesus, extra money than God, cash that might purchase something they wished. And what they wished, greater than something, it appeared, was to be British. Abramovich wished to be British a lot that he had purchased a soccer crew, a plaything within the self-styled best league on this planet. His cash added just a bit additional spice, an additional sprint of glamour, to the Premier League’s endlessly spinning drama; his cash served to make the good English mushy energy undertaking just a bit extra engaging.

It was only some years later that the second story emerged, within the aftermath of the jailing of Mikhail Khodorkovsky and the poisoning of Alexander Litvinenko. Maybe, the thought was floated, Abramovich had not fallen in love with soccer; or, somewhat, he had not solely fallen in love with soccer. Maybe he did have an ulterior motive. Chelsea, in any case, didn’t simply present him with entry to the very highest echelons of British society; it gave him a profile, a fame, too.

He didn’t appear to relish it, significantly — “at some point they may overlook me,” he had stated, in one of many uncommon interviews he has granted since arriving in England — however he appeared ready to consider it a value value paying. Being an oligarch was a harmful enterprise. Chelsea, maybe, was Abramovich’s safety in opposition to the shifting tides within the Kremlin.

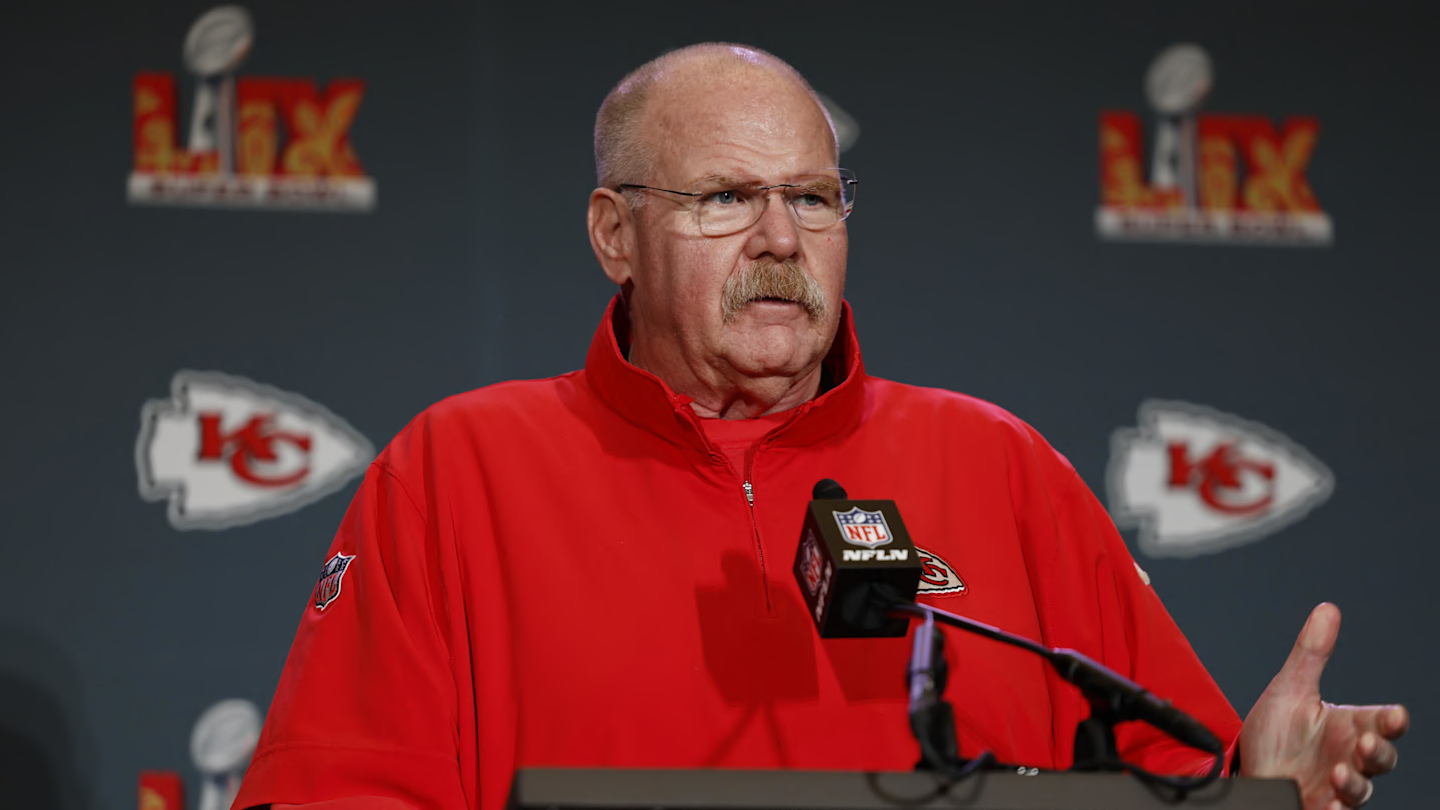

That was the story we advised ourselves as Chelsea went from usurper to institution, the membership that originally impressed the thought of cracking down on arriviste wealth all of a sudden recast as one in all its foremost advocates. It was the story that took root as Chelsea racked up Premier League titles, because it conquered Europe not as soon as, however twice: that soccer was the sanctuary, the final word mark of acceptance.

It was solely, actually, when others began to adapt Abramovich’s playbook that the narrative was challenged. First one after which two Premier League groups fell below the aegis of nation states, or of entities so intently aligned to nation states that it may be tough to inform the distinction until you actually, actually need to squint. The thought of sportswashing bled into the dialog. The sense that soccer was getting used took root. Abramovich’s doable motives had been reconsidered.

After which, on Thursday, we noticed for the primary time — plain as day — what the aim of all of it had been, the story in its true, unvarnished type. For 2 weeks, the British authorities had dallied over making use of sanctions to Abramovich, not essentially the richest and even essentially the most highly effective however nonetheless by far essentially the most high-profile of all the caste of oligarchs, the face of oligarchy within the west.

A stunning portion of these two weeks, it turned out, had been spent looking for a technique to make it possible for Chelsea may proceed to perform, roughly as regular, as soon as Abramovich’s different belongings had been frozen. The gamers, the employees and the followers — particularly the followers — should not endure, the federal government stated. Just a few hours earlier, Russian artillery had shelled a maternity hospital in Mariupol, Ukraine. However the authorities was clear: The sanctity of the Premier League couldn’t be sullied.

That was the aim all alongside, it appeared. Abramovich most likely did cherish the profile that proudly owning Chelsea introduced him. He actually appeared to relish the game.

However primarily, he had come to soccer as a result of it entangled him in British society in a manner that proudly owning another enterprise merely wouldn’t. Not one of the different oligarchs who’ve been sanctioned have been given a bespoke “license” to proceed working one in all their companies. That’s not, in any case, how sanctions are imagined to work. It had taken us 19 years, and the demise of hundreds of Ukrainians, to appreciate that, to see the world because it was.

Now, eventually, we all know why Abramovich was right here. Now, eventually, we will start to grasp the worth we now have all paid. It’s not solely Chelsea that should now withstand an unsure future: not solely the following few months, because the membership picks by means of the thicket of restrictions on its existence — its membership retailer closed, its resort not permitted to promote meals and hire rooms, its crowds restricted to season-ticket holders — however past, too.

The membership may but slide into chapter 11, offered off to the very best bidder by the federal government. Or maybe it is going to wither, slowly and irrevocably, its gamers leaving at any time when they’re permitted, the membership unable to signal replacements. Possibly there can be peace, and an easing of the sanctions, and possibly Abramovich can recoup his funding and his loans. Irrespective of the way it performs out, there is no such thing as a going again. The followers don’t, and can’t, know what comes subsequent. It’s as much as them to resolve if the reminiscences and the trophies had been value it.

The echoes of Abramovich’s swift, abrupt exit, nonetheless, will perform additional into the sport. His arrival marked the beginning of what’s going to come, in time, to be considered soccer’s oligarch age. It was Abramovich, as famous final week, whose arrival kick-started the inflationary spiral that has fractured European soccer past restore, with solely a handful of golf equipment hoarding all the wealth of the sport, ruthlessly stripping its pure sources for his or her profit.

His departure will show to be no much less epoch-defining. Trendy elite soccer is constructed on progress, the self-esteem that there’s all the time extra money on the market. That’s the reason Actual Madrid and Juventus and Barcelona need, so fervently, to launch a European Tremendous League, as a result of they’re satisfied that if solely they didn’t should take care of UEFA, they’d be capable of harvest the bottomless riches of all the broadcasters and sponsors determined to fill their accounts.

It’s why UEFA has been so decided to broaden the Champions League, so satisfied that it may well discover the cash to satiate the boundless greed of the good and the great. All of it’s based mostly not solely on the concept that the golden goose will maintain laying, however the religion that there are 100, a thousand extra golden geese on the market, an entire flock of them.

If that was ever true, it isn’t now. UEFA will discover one other sponsor for the Champions League to interchange Gazprom, but it surely won’t discover one that’s fairly so beneficiant. There’s, in any case, a premium to be paid for exercising mushy energy. Exponential progress is somewhat more difficult when one of many prime drivers of it has closed down.

So, too, the golf equipment face a reckoning. Not solely the groups owned by princelings and nation states and politicians, however these that aren’t. It’s not simply the promise of hovering tv rights offers which have drawn the “acceptable” traders into soccer, the non-public fairness teams and the hedge funds and the Wall Avenue speculators. They don’t have any extra fallen in love with the sport than Abramovich.

All of them have purchased in to get out, in some unspecified time in the future sooner or later, once they have made their golf equipment as worthwhile as doable, when the prospect of a profitable return is at hand. And but, abruptly, they discover their record of potential patrons restricted. Qatar, Abu Dhabi, Saudi Arabia: All of them have their golf equipment now. The nice gushing of money from China ended years in the past, as Inter Milan would possibly attest. Now Russian cash is out of the query, too.

There is no such thing as a scarcity of the wealthy and the highly effective and the speculative, after all, even with these markets closed up and sealed off. However people who stay are a special sort of purchaser: They’re different non-public fairness companies, different hedge funds, different Wall Avenue and Silicon Valley varieties. They’re, for essentially the most half, those who need to make a revenue. They don’t need to be those who purchase on the peak of the market. They didn’t make their cash by being the sucker.

Which may appear, maybe, a bit vague, a contact theoretical, but it surely has actual penalties. It means reassessing how a lot revenue may be made, and the way massive the payout may be. That, in flip, means altering the equation of how a lot it’s value placing in. The change won’t be instant, in a single day, dramatic. However it is going to be a change nonetheless.

That can be Abramovich’s final legacy, the lasting influence of the period he started on what gave the impression to be a whim and he ended, within the area of a few weeks, in the midst of a battle. Soccer’s age of the oligarch is over. This time, there may be no excuse for failing to grasp what the sport has turn into. On that, we now have readability. The place it goes from right here stays shrouded doubtful.

We might be right here for a very long time if I listed each single Brooklynite who wrote in, final week, to tell me that there are, because it occurs, a number of cricket grounds in Brooklyn. There are such a lot of, the truth is, that my impression now could be that there’s little however cricket grounds in Brooklyn, and so if something it maybe must diversify its sporting choices a bit.

The precise variety of cricket grounds in Brooklyn stays the topic of fevered debate. Fritz Favorule pitched 5, with the point out of a Brooklyn Cricket League, too, whereas Laurence Bachmann made point out of “no less than half a dozen that I do know of,” somewhat suggesting the actual quantity could possibly be within the hundreds.

Credit score to Laurence, too, for being the one correspondent prepared to tackle the thornier aspect of that equation. “There are millions of bakeries,” he added. That could be, Laurence, however do any of them do a steak slice? (Admittedly, he vouches for his or her sausage rolls, which is an efficient begin.)

Sorry, regardless, for inflicting such offense in what’s, with out query, one of many prime 5 New York boroughs. If I’m trustworthy, I don’t assume Brooklyn significantly wants to fret about competitors from Headingley.

On a much less fractious observe, thanks to Felipe Gaete for providing a Chilean perspective on Bielsa. It was Chile, you’ll keep in mind, that Bielsa remodeled for a number of, wondrous years into the foremost energy in South American soccer. “I’ve thought quite a bit about why he’s so liked in a area by which silverware is all that issues,” Felipe wrote.

“I feel he holds a great deal of the values that many people know are proper, however can’t afford to use: He provides again a purpose within the title of honest play. He’s additionally an incarnation of what the vast majority of followers get pleasure from essentially the most: hope. The enjoyment of profitable is normally very quick in contrast with the sense of what it would turn into.”

That could be a fantastic, and correct, sentiment, Felipe, so it appears becoming to go away you with the final phrase.

Culture

Book Review: ‘Death Is Our Business,’ by John Lechner; ‘Putin’s Sledgehammer,’ by Candace Rondeaux

Western complacency, meanwhile, stoked Russian imperial ambition. Though rich in resources, Rondeaux notes, Russia still relies on the rest of the world to fuel its war machine. Wagner’s operations in Africa burgeoned around the same time as their Syrian operation. In 2016, the French president François Hollande “semi-jokingly” suggested that the Central African Republic’s president go to the Russians for help putting down rebel groups. “We actually used Hollande’s statement,” Dmitri Syty, one of the brains behind Wagner’s operation there, tells Lechner.

“Death Is Our Business” provides powerful descriptions of the lives that were upended by the mercenary deployments. Wagner is accused of massacring hundreds of civilians in Mali in 2022, and of carrying out mass killings alongside local militias in the Central African Republic. “Their behavior mirrored the armed groups they ousted,” Lechner writes. As a Central African civil society activist whispers to Lechner, “Russia is no different” from the sub-Saharan country’s former colonial power, France.

Both books are particularly interesting when they turn their focus toward Europe and the United States. In Rondeaux’s words, the trans-Atlantic alliance does not “have a game plan for countering Russia’s growing influence across Africa.” Lechner, who was detained while reporting his book by officials from Mali’s pro-Russian government, is even more critical. He notes that, whatever Wagner produced profit-wise, the sum would have “paled in comparison to the $1 billion the E.U. paid Russia each month for oil and gas.”

And, while Wagner was an effective boogeyman, mercenaries of all stripes have proliferated across the map of this century’s conflicts, from the Democratic Republic of Congo to Yemen. “The West was happy to leverage Wagner as shorthand for all the evils of a war economy,” Lechner writes. “But the reality is that the world is filled with Prigozhins.”

Lechner is right. When Wagner fell, others rose in its stead, although they were kept on a tighter leash by Russian military intelligence. In Ukraine, prisoners are still being used in combat and Russia maintains a tight lid on its casualty figures. Even if the war in Ukraine ends soon, as President Trump has promised, Moscow’s mercenaries will still be at work dividing their African cake. Prigozhin may be dead, but his hammer is still a tool: It doesn’t matter if he’s around to swing it or not.

DEATH IS OUR BUSINESS: Russian Mercenaries and the New Era of Private Warfare | By John Lechner | Bloomsbury | 261 pp. | $29.99

PUTIN’S SLEDGEHAMMER: The Wagner Group and Russia’s Collapse Into Mercenary Chaos | By Candace Rondeaux | PublicAffairs | 442 pp. | $32

Culture

Test Yourself on Memorable Lines From Popular Novels

Welcome to Literary Quotable Quotes, a quiz that challenges you to match a book’s memorable lines with its title. This week’s installment is focused on popular 20th-century novels. In the five multiple-choice questions below, tap or click on the answer you think is correct. After the last question, you’ll find links to the books themselves if you want to get a copy and see that quotation in context.

Culture

Book Review: ‘How to Be Well,’ by Amy Larocca

HOW TO BE WELL: Navigating Our Self-Care Epidemic, One Dubious Cure at a Time, by Amy Larocca

Oh, the irony of cracking open “How to Be Well” while on vacation in Italy. There, on an island off the coast of Naples, a breakfast buffet included three varieties of tiramisu. Wine was poured not to a stingy fingertip’s depth but from a bottomless carafe — at lunchtime, no less. And when stores closed in observance of an afternoon siesta, the only people on the streets were American tourists, jogging. (I was on the prowl for a postage stamp because, yes, I still send postcards.)

It was from this place of abundance and balance that I followed Amy Larocca, a veteran journalist, into the hellscape of stringent food plans, cultish exercise routines and medical quackery that have, over the past decade or so, constituted healthy living in some of the wealthiest enclaves of the United States. Blame social media, political turmoil or the pandemic — no matter how you slice it, the view is dispiriting. But Larocca’s tour is a lively one, full of information and humor.

The book begins with a colonic, “the flossing of the wellness world,” Larocca writes. We find the author herself on an exam table, “white-knuckled and curled up like a baby shrimp, naked from the waist down.” She recalls her doctor’s disapproval of the procedure — a sort of power washing of the colon — and its risks, including rectal perforation, juxtaposed with one woman’s claim that a colonic made her feel like she could fly, like it was “rinsing out the corners of her psyche.”

Where did we get the idea that the body — specifically a woman’s body — is unclean inside? A problem to be solved? And how did the concept of wellness bloom “like a rash,” Larocca writes, into a $5.6 trillion global industry?

These are the questions she seeks to answer, using data, history, medicine, pop culture and her own experience. She parses fads and trends, clean beauty and athleisure wear, the gospel of SoulCycle and the world according to Goop. She weighs the advantages and disadvantages of micro-dosing and biohacking. She too goes to Italy, where she attends a Global Wellness Summit featuring a spandex and sneaker fashion show and a presentation on ending preventable chronic disease the world over.

At times, Larocca seems to approach her own subject with the same sweep. The second half of “How to Be Well” reads like a survey course, cramming the industry’s relationship to politics, men and the environment into single chapters when each could fill a whole semester. As for why meditation merits more real estate than vaccines, I can only assume that the book was already at the printer when Robert F. Kennedy Jr. was confirmed as health secretary.

But when Larocca goes deep, as she does on self-care, body confidence and sex positivity, she’s at her best — authoritative and witty, personal without being chummy.

She debunks the cockamamie but persistent notion that “feeling old is not an inevitable byproduct of aging but something easily avoided by paying attention.” (And by forking over gobs of cash; more on this shortly.) After attending an Oprah-sponsored conference on menopause, a subject Larocca has covered for The New York Times, she realizes that “aging is different from disease” and “isn’t necessarily something to be cured,” let alone through “neat, tidy, attainable solutions.”

Then there’s the sneaky rebranding of old-school dieting for “detoxification,” another wolf in sheep’s clothing. Think fasting, juicing, abstaining from all manner of verboten foods. Even if the professed endgame is “glow,” Larocca makes clear, “part of the promise is still, always, to rid us of a bit of ourselves.”

And finally, refreshingly, she’s honest about the money at stake for the wellness-industrial complex — not just for stylists turned wellness coaches or models turned nutritionists, but for massive corporations cashing in on an age of worry.

“None of these institutions is nonprofit; none of these institutions is altruistic at its core,” Larocca writes, in a passage reminiscent of Carol Channing’s monologue from “Free to Be You and Me,” in which she reminded us that happy people doing housework on TV tend to be paid actors.

“It is their job to persuade me to come back,” Larocca continues, “to spend more money on what they’ve got to give, to serve their investors, to serve themselves.”

And that, as “How to Be Well” wisely shows us, is the bottom line.

HOW TO BE WELL: Navigating Our Self-Care Epidemic, One Dubious Cure at a Time | By Amy Larocca | Knopf | 291 pp. | $28

-

Cleveland, OH1 week ago

Cleveland, OH1 week agoWho is Gregory Moore? Former divorce attorney charged for murder of Aliza Sherman in downtown Cleveland

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoFamily statement: Rodney Hinton Jr. walked out of body camera footage meeting with CPD prior to officer death

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoTrump posts AI image of himself as Pope amid Vatican's search for new pontiff

-

Austin, TX3 days ago

Austin, TX3 days agoBest Austin Salads – 15 Food Places For Good Greens!

-

Technology7 days ago

Technology7 days agoBe careful what you read about an Elden Ring movie

-

Culture1 week ago

Culture1 week agoPulitzer Prizes 2025: A Guide to the Winning Books and Finalists

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoFather Whose Son Was Shot by Cincinnati Police Hits Deputy With Car, Killing Him

-

Education1 week ago

Education1 week agoIn Alabama Commencement Speech, Trump Mixes In the Political