Culture

‘Mockingbird’ Made Her a Child Star. Now She’s in the Broadway Tour.

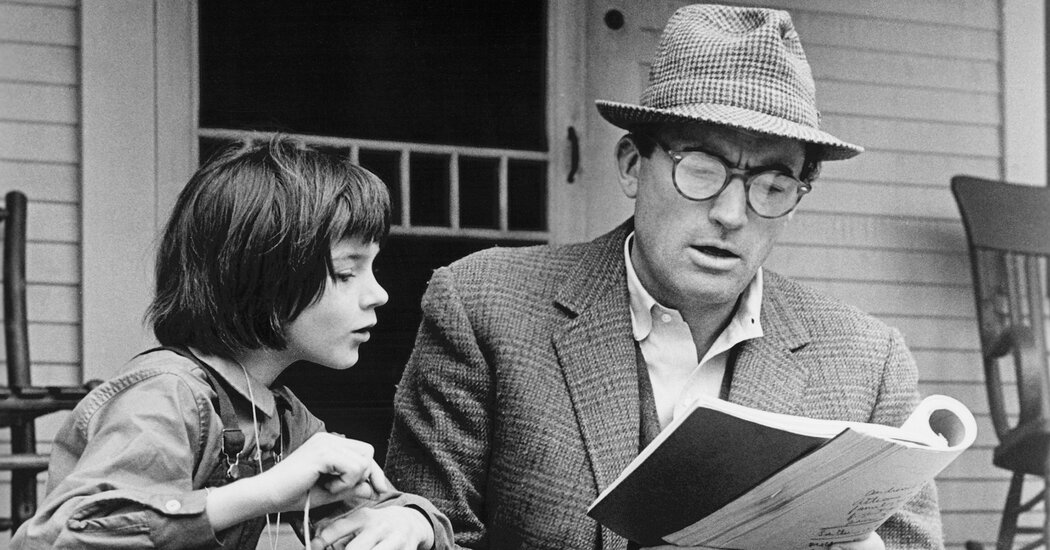

Mary Badham describes herself as “only a retired outdated woman who likes to be in her backyard and play together with her grandkids.”

However in 1962 she was a baby star, fascinating the nation together with her Oscar-nominated portrayal of Scout, the daughter of Atticus Finch, within the movie model of “To Kill a Mockingbird.”

Now, six a long time and plenty of careers later, she helps to dramatize the story as soon as once more, this time from a unique vantage level. Badham, who has not beforehand labored as a stage actor, is now in rehearsals for a nationwide tour of the “Mockingbird” Broadway manufacturing during which she’s going to play Mrs. Dubose, Scout’s imply, and morphine-addicted, neighbor.

“I’m going full circle,” Badham mentioned in an interview. “That is one thing I by no means contemplated.”

Badham, now 69, remains to be slightly hazy on how this occurred. She says she acquired a name out of the blue from the manufacturing, inviting her to audition. The play’s director, Bartlett Sher, mentioned Badham’s title had come up throughout brainstorming for the tour, and that the casting group had tracked her down; he mentioned as quickly as he noticed her do a workshop, he knew she may do it.

“She has not been on a stage, and that was a giant adjustment for her, however she’s going to be nice — she has a vibrant, blazing intelligence, and good listening and sharp supply and all of the belongings you want as an awesome actor,” Sher mentioned. “And it was extremely fascinating — I’ve by no means had an expertise fairly prefer it, to have this voice from the cultural historical past of the very work we have been doing, and to see how we’ve modified and the way she’s modified. It was stunning to have her within the room.”

Badham has all the time been a little bit of an unintentional actor. She had no expertise when a expertise scout confirmed up in Birmingham, Ala., the place she lived, on the lookout for a Southern woman to star as Scout within the movie adaptation of Harper Lee’s Pulitzer Prize-winning 1960 novel a couple of white Alabama lawyer — Finch — who agrees to characterize a Black man accused of rape. Badham’s mom carried out in native theater, and her brother (who turned a movie director) was in drama college; she aced a display screen take a look at, and earlier than she knew it, she was off to California, performing alongside the actor Gregory Peck, who turned an necessary mentor and buddy.

“I had no concept what was occurring — I used to be simply on the market taking part in,” she mentioned. “I don’t even suppose we acquired full scripts, as a result of there have been sure phrases and issues that have been deemed unseemly for kids to listen to. I didn’t have a clue what the movie was about till we began going to premieres, after which all of us have been in tears.”

Within the a long time since, Badham has labored promoting cosmetics, turned an authorized nursing assistant, and even often appeared on movie and tv. She by no means turned a big animal veterinarian — her childhood aspiration — however, alongside together with her husband and two youngsters, she did make a Virginia farm her residence. “I all the time needed to stay on a farm and have horses and animals, and we’ve had that by the years,” she mentioned.

“I’m not an actor,” she added. “Appearing is one thing that has simply occurred to me.”

She mentioned she has a tough time watching the movie “as a result of all my mates are gone now — there’s just a few of us left.” However she often says sure when given new “Mockingbird” alternatives; she has spent a long time speaking in regards to the story at faculties, universities and social golf equipment. “‘Mockingbird’ has been my life,” she mentioned.

“It’s simply bizarre, and I put it to the person upstairs — I simply really feel like he has one thing he needs me to say, and he picked me to say it and hold saying it,” she added. “My job has been principally to maintain this story alive, and have individuals discuss it, so we will attempt to transfer ahead with all of those issues that we nonetheless have.”

And what’s the message of “Mockingbird”? “We should always attempt to study to like one another and be good individuals,” she mentioned.

The present’s tour, led by Richard Thomas as Atticus and Melanie Moore as Scout, begins performances on March 27 in Buffalo and opens on April 5 in Boston, adopted by runs across the nation. This adaptation, written by Aaron Sorkin, opened on Broadway in 2018, had an enormously profitable run earlier than the pandemic and bought strongly once more when Jeff Daniels returned to guide the solid as Atticus Finch. As Daniels departed and the Omicron variant surged, the present introduced it was taking a virtually six-month hiatus, with a deliberate resumption in a smaller theater on June 1. A London manufacturing is scheduled to start performances on Thursday.

Badham mentioned she agonized over whether or not to play Mrs. Dubose, as a result of the character makes use of racist language to explain Black individuals. “I had an actual drawback with accepting this position, as a result of I’ve to make use of the N-word, and I’ve to be this horrible, bigoted, racist particular person,” she mentioned. “I went to my African American mates, and mentioned, ‘Do I wish to stroll round within the pores and skin of this terrible outdated woman?’ They usually have been like, ‘That is necessary. That is a part of the story. It’s a must to go on the market and make her as imply as you’ll be able to, and present what it was actually like.’”

Badham additionally mentioned she believes that the character of Mrs. Dubose, as a morphine addict, is necessary at a time when many Individuals are combating opioid addictions. “That offers me one other aspect of the story to focus on,” she mentioned.

After just a few weeks of rehearsal, she mentioned she is feeling extra snug.

“It’s scary — I’ll let you know level clean, I’m mortally terrified each time I’ve to open my mouth, and I had no concept I used to be going to be onstage a lot,” she mentioned.

However, she mentioned, she will be able to really feel the presence of others who’ve informed the story earlier than, and that strengthens her. “I really feel like they’re with us, supporting us,” she mentioned, “as a result of they know this must be mentioned.”

Culture

‘Dean of American Historians’: Ken Burns on William E. Leuchtenburg

Ken Burns was in his studio working on the final edits of a forthcoming documentary film series on the American Revolution when he learned on Tuesday that the historian William E. Leuchtenburg had died at 102.

“I had to get up and go be by myself for a while,” Mr. Burns said in an interview. “Everything just crashed to a halt.”

In his view, Mr. Leuchtenburg was “one of the great historians, if not the dean of American historians in the United States, for his work on the presidency.”

For more than 40 years, Mr. Leuchtenburg was a close adviser and friend to Mr. Burns, appearing in three of his documentaries — “Prohibition” (2011), “The Roosevelts: An Intimate History” (2014) and “Benjamin Franklin” (2022) — and consulting on many more.

The Times spoke to Mr. Burns on Wednesday about Mr. Leuchtenburg’s career. His observations, lightly edited and condensed for clarity, are below.

A Friendly Correspondent

He would send me notes all the time. My files are filled with these notes with little schoolboy handwriting. It reminded me of the way I wrote cursive when I was in the eighth grade. I just want to imagine that he had a filing system that looked like the cavernous place at the end of “Citizen Kane” or “Raiders of the Lost Ark,” because he could not have had so many references at his hand. He would just bring them up. It might be baseball, which he and I both passionately loved. It might be jazz. It might be World War II. Obviously the presidency. Vietnam. Really all of the kinds of things that we’ve done. He had an interest in what we were doing and how we were doing it that made him an extraordinarily helpful contributor.

Baseball and Booze

He made particularly important contributions to our history of baseball, to the Second World War, to our Prohibition film — in which we learned personally from him the very, very complicated internal dynamics, not just about what took place in Prohibition, but his own personal family life in which both his parents were alcoholics. And so the repeal for him was not a good thing. He also understood, hilariously and intimately, the sexual revolution that was going on in the 1920s among women, and just flat-out said that people discovered the clitoris. And that was, like, whoa!

Picturing the Depression

He was a storyteller. All you need to do is go into the fifth episode of the Roosevelt series and look at his concise way of explaining what it was. He first talks about filling up a stadium with people and then emptying it and then filling it up again. And if you did this over and over again, you would get the number of people who had gone out of work. It was just such a vivid description.

Working Without Him

I’m going to cry talking about it, but it’s just this gigantic and unfillable hole. He taught us well, though. He’s imparted not just facts, but attitudes and relationships and methodologies that we’ll save. We’ll be poorer for not having Bill to come and look at a rough cut of something that he shouldn’t know anything about but then inevitably knows a ton. We’ll muddle through.

Culture

Ahead of 2025 debut, Scottie Scheffler details how he hurt hand in ‘stupid’ kitchen accident making ravioli

PEBBLE BEACH, Calif. — Scottie Scheffler was attempting to make homemade ravioli on Christmas Day — with limited equipment in a rental home — when he realized he’d made a serious mistake. He decided to use an empty wine glass to shape and slice his pasta dough.

“I had my hand on top of it and it broke, which, side note, I’ve heard nothing but horror stories since this happened about wine glasses, so be careful,” Scheffler said Tuesday. “Even if you’re like me and you don’t drink wine, you’ve got to be real careful with wine glasses.”

The stem of a wine glass stabbed Scheffler in the upper palm of his right hand. That’s the crux of the incident that led to a surgical procedure and took the 2024 PGA Tour Player of the Year out of his first two tournaments of the season, The Sentry in Maui and the American Express in Palm Springs.

The No. 1 player in the world is making his first tournament start of 2025 this week at the Pebble Beach Pro-Am, which begins on Thursday. It comes after a two-week long hiatus from golf and physical activity, as well as a steady process of easing back into training and playing. That period was frustrating for a player who thrives in competition. Scheffler doesn’t like to sit back and watch.

“It’s one of those deals where immediately after it happened, I was mad at myself because I was like gosh, that’s so stupid, but you just don’t think about it when you’re in the moment,” he continued. “Yeah, definitely been a little more careful doing stuff at home.”

Immediately after the incident, a friend of Scheffler’s who happens to be a surgeon came to the rescue and helped stop the bleeding. The next day rolled around and the wound was no longer open, but the pain remained, and Scheffler felt a general lack of range of motion. He decided to reach out to a hand doctor he’d worked with on a thumb injury while in college. They opted for surgery. Scheffler said that he does not expect his right hand to incur any long-term damage.

Scheffler spent his recovery time reflecting and analyzing an historic season that included seven wins on the PGA Tour — the most since Tiger Woods won seven in 2007 — plus an Olympic gold medal and the Hero World Challenge. He re-watched film of his tournament rounds and took his mind back to those cruise-control moments in competition, taking note of both his swing positions and demeanor.

“There’s a few tournaments I looked back at where the thing that stuck out the most was that I never really overreacted to stuff, I kind of stayed in it and kind of waited for my moment to get hot,” Scheffler said.

Required reading

(Photo: Kevin C. Cox / Getty Images for The Showdown)

Culture

Book Review: ‘Talk,’ by Alison Wood Brooks

She also warns about “candidate answers,” a kind of leading the witness, in which one asks an open-ended question only to narrow it down in anticipation. (As in: Why are you reading a book about how to improve your conversations? Do you think you have room to grow, or are you just hoping to feel superior?) I realized that I curtail my questions this way all the time; leaving them open has actually expanded the answers I receive.

Brooks is a companionable writer, and she’s alive to the absurdity inherent in her project. Talk is messy, and good talk messier still; templates, instructions and guardrails are generally self-defeating. Kant, she notes, hosted dinners that adhered to a strict script: Guests spoke during the first course of headlines and the weather before proceeding, with their entrees, to politics and the sciences. Dessert came with “jesting.” Games, beer and music were forbidden; lulls were unpardonable. Though Brooks lauds the philosopher’s ambition, she prefers her conversations faster and looser — something, she says, like Arlie Hochschild’s description of “the jazz of human exchange.”

But I couldn’t hear the jazz in “Talk”’s pages of diagrams and graphs, among them a “conversational compass,” a “topic pyramid” and a “chart of emotions.” Brooks’s rigid, evidence-based approach means that she must frequently write things that I suspect she would find obvious or trite in conversation, such as, “It’s not just about choosing topics, but also deciding what to say about them.” By the time I read that talking like a rude cop at a traffic stop “is likely to make your friends, your romantic partner, your mom and everyone else uncomfortable in less charged circumstances, too,” I was about ready to take a vow of silence.

Parts of “Talk” feel designed not to help humans communicate but to train A.I. This is especially evident in the section on levity, which advises “livening up your texts by sending Onion headlines to your friends” and imitating the outsize reactions of “Seinfeld” characters.

Is this what it feels like to be optimized? I don’t know why I say half the things I say, and I often want my conversations to roam elsewhere, but to make “spreadsheets filled with promising topics to raise with strangers,” as some of Brooks’s students do, would make me feel even less human than I already do.

-

Culture1 week ago

Culture1 week agoBook Review: ‘Somewhere Toward Freedom,’ by Bennett Parten

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoJudges Begin Freeing Jan. 6 Defendants After Trump’s Clemency Order

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoHamas releases four female Israeli soldiers as 200 Palestinians set free

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoInstagram and Facebook Blocked and Hid Abortion Pill Providers’ Posts

-

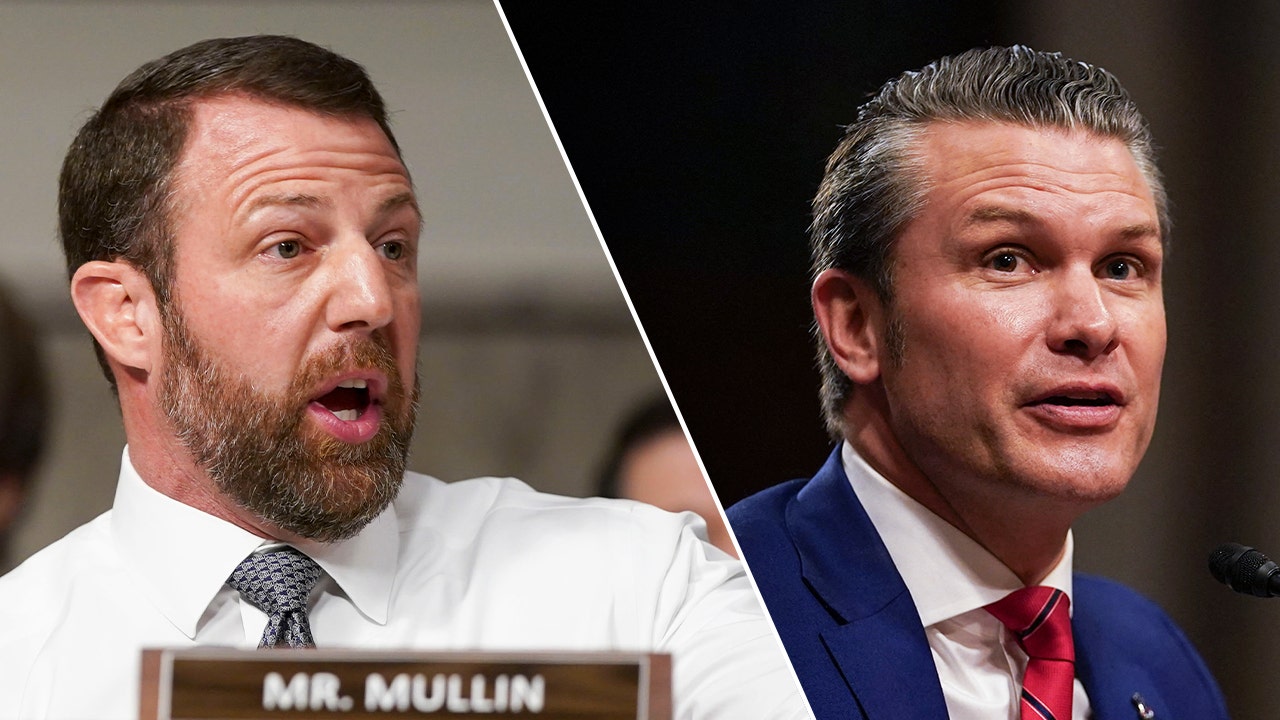

Politics6 days ago

Politics6 days agoOklahoma Sen Mullin confident Hegseth will be confirmed, predicts who Democrats will try to sink next

-

Culture3 days ago

Culture3 days agoHow Unrivaled became the WNBA free agency hub of all chatter, gossip and deal-making

-

World5 days ago

World5 days agoIsrael Frees 200 Palestinian Prisoners in Second Cease-Fire Exchange

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoA Heavy Favorite Emerges in the Race to Lead the Democratic Party