Business

This California city lost its daily newspapers — and is living what comes next

For years Richmond City Councilmember Cesar Zepeda has been on an unsuccessful crusade to persuade the grocery store chains of America — or at least one of them — to bring a supermarket back to his industrial city on the edge of the San Francisco Bay.

He’s persistent. He’s called corporate headquarters. He’s emailed customer relations. Occasionally, he’s gotten executives on the phone, and listened to them stammer on about why Richmond isn’t the right place for them to locate a store, despite its population of 117,000 in the heart of the Bay Area.

After years of disappointing conversations, Zepeda has concluded something basic about his city: It is paying a big price by not being able to tell its own story.

Richmond has not had its own daily newspaper for years. The loss came during a period of profound struggles for the town, which has dealt with fluctuating crime, economic problems and environmental challenges. Zepeda and others say there is a lot of good and bad going on in Richmond, but the dearth of local news coverage offers a skewed view of the city — oversimplified and years out of date — as an impoverished and violent community.

“The lack of coverage puts us into deserts of everything. We have a hospital desert. We have a grocery store desert,” Zepeda said. “Just the lack of any coverage, it affects the perception.”

In this news desert, the main information source has been the Richmond Standard, a news website funded by Chevron, Richmond’s largest employer. It offers reports on youth sports, crime logs and things to do in town. Recent articles have highlighted a mural project, a car caravan supporting racial justice and upcoming closures to Interstate 80.

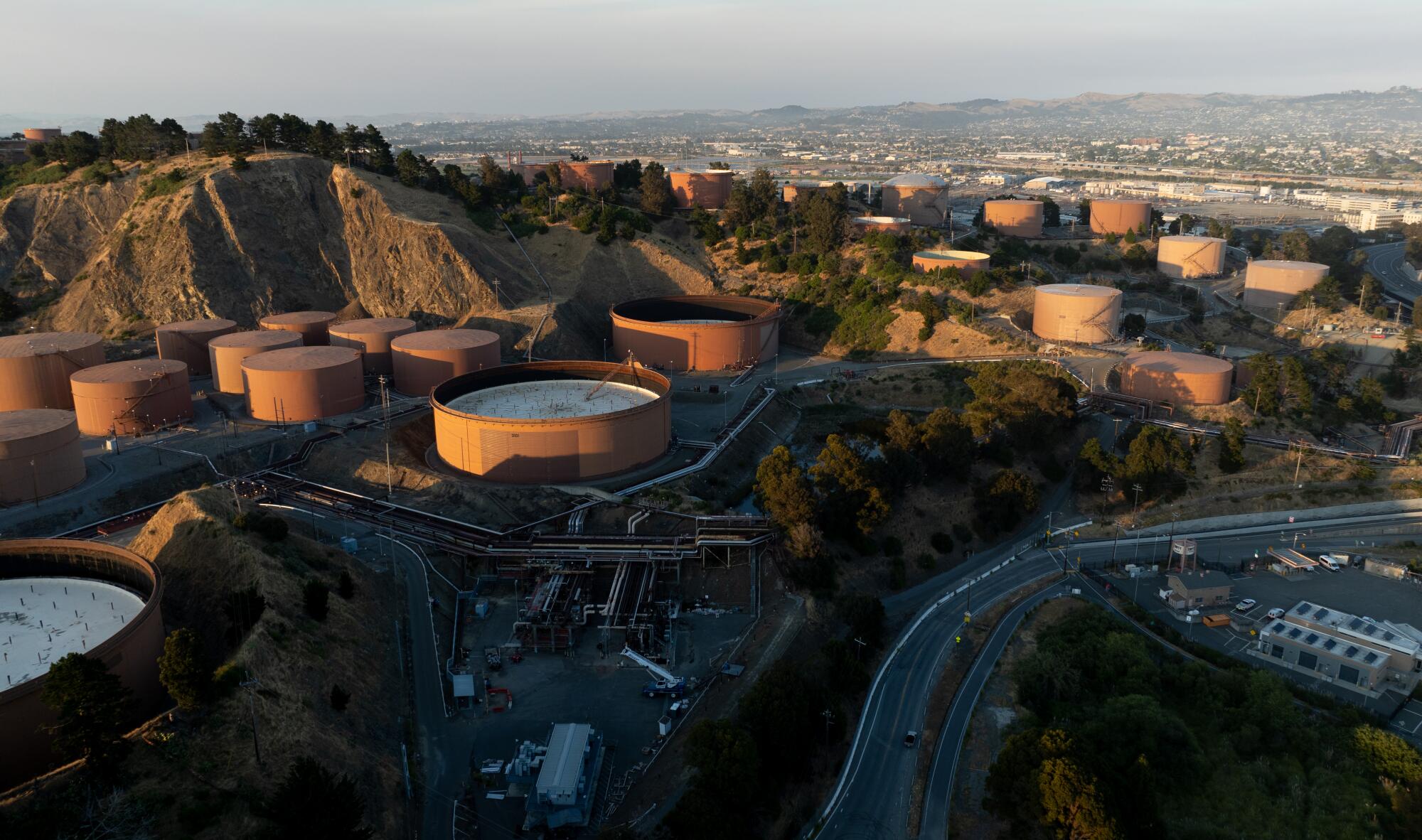

But the Standard is conspicuously silent when it comes to hard-hitting reporting on the Chevron refinery, which activists blame for the city’s high rates of hospitalization for childhood asthma. On June 19, the City Council voted to put a measure on the November ballot asking local voters to levy a tax on the refinery that would generate tens of millions of dollars a year to be used as the city sees fit. The lead-up and follow-up to this hugely consequential development were nowhere on the Standard’s homepage.

Richmond is one in a swelling number of California communities that in recent years have had to navigate civic life without a traditional newspaper. The city — a onetime shipbuilding hub that fell on hard times and is now in the midst of a rebound — was once served by multiple papers, but the grim economics took them out one by one.

All the while, in-depth daily coverage of Richmond, a city with 23 distinct neighborhoods and cutthroat politics, with a refinery of vital importance to the state’s energy economy, shrank and shrank.

“The lack of coverage puts us into deserts of everything. We have a hospital desert. We have a grocery store desert.”

— Zepeda Richmond City Councilmember Cesar Zepeda

Councilmember Cesar Zepeda says the dearth of local news coverage in Richmond has resulted in a skewed portrayal of his city, making it harder to draw retailers.

(Josh Edelson / For The Times)

The issue of California’s growing news deserts — and the fallout on civic engagement — has become a heated topic in the state Legislature, where Assemblymember Buffy Wicks (D-Oakland) is pushing a measure, Assembly Bill 886, that would require leading social media platforms and search engines to pay news outlets for accessing their articles, either through a predetermined fee or through an amount set by arbitration. Publishers would have to use 70% of those funds to pay journalists in California. Lawmakers are also considering state Senate Bill 1327, which would tax large tech platforms for the data they collect from users and pump the money into news organizations by giving them a tax credit for employing full-time journalists.

AB 886 is sponsored by the California News Publishers Assn., whose members have argued for years that online search engines and social media platforms are gutting the newspaper business by gobbling up advertising revenue while publishing content they don’t pay for. (The Los Angeles Times is a CNPA member, and its business leaders have publicly supported the measure.)

The legislation has drawn staunch opposition from Google and other tech companies, which contend it would upend their business model.

The rise of the search engine is one of many factors pushing California newspapers out of business. Richmond’s news decline began well before eyeballs and advertising migrated online.

But Richmond’s story is not just about the loss of news. It also shows how a community gets information in a post-newspaper world.

Richmond is now a laboratory for online journalism startups, including the one owned by Chevron, whose massive refinery looms over the city and has been the focus of ongoing concerns over toxic emissions.

Protesters rally in support of putting a measure on the November ballot that would levy a new tax on Chevron’s refinery, generating millions of dollars annually for city coffers.

(Josh Edelson / For The Times)

The region’s independent online publications are sometimes hard-hitting and admirably hardworking, but they are limited in size and reach. The students at UC Berkeley’s journalism school operate Richmond Confidential, a news lab for student reporters that is funded by a grant from the Ford Foundation. Since late 2020, the husband-and-wife team of Linda and Soren Hemmila have put out the Grandview Independent, whose website proclaims: “For us, there is no story too small.”

There is also a youth-focused site, the Pulse, and a publication that focuses on the area’s Black community. In late June, the team behind the well-regarded local news websites Berkeleyside and Oaklandside launched a sister publication called Richmondside.

Still, said City Councilmember Doria Robinson, “the unfortunate best source” for much of the day-to-day goings on in recent years has been the Richmond Standard.

Councilmember Doria Robinson finds it troubling that Richmond residents get their daily news from a site funded by Chevron, the town’s biggest employer and a source of controversy.

(Josh Edelson / For The Times)

Robinson is a third-generation Richmond resident who was elected to the council in 2022 and for years before that ran a nonprofit farm in North Richmond. She said she is grateful for the work of all the reporters laboring on a shoestring to bring news to her city. But it doesn’t replace the weight and influence of the local paper she remembers from her youth.

And as for the Chevron paper, she said: “It is just unfortunate to have to depend on a project that is openly and proudly funded by our local petroleum [company].”

In 2011, the news group that owned the West County Times made an announcement that had become all too familiar to Richmond readers: More layoffs and cuts were coming to the chain that published the West County Times along with several other outlets in the East Bay. There would be less news out of Richmond.

Former Councilmember Tom Butt, who sends out an email about Richmond that doubles as an informal newsletter, lamented the decision and urged citizens to complain, writing: “What will this mean for Richmond? Undoubtedly, it will mean reduced coverage of local news.”

Five years later, in 2016, the ax swung again, and the West County Times was merged, along with a number of other newspapers, into two. Another chunk of the reporting staff was cut.

“The level of connection we were able to maintain with people in the community really evaporated in a significant way,” said Craig Lazzeretti, a journalist who covered the region for 30 years, much of it in Richmond. Over time, Richmond lost its education and public safety reporters, he said, and while City Hall remained a priority, coverage of sports and entertainment also declined.

In its heyday, the coverage was rigorous, and “it did play a significant role” in civic life, Lazzeretti said. “You had a lot of strong political personalities in Richmond.”

He admits the local newspapers of that era were not perfect: “We were covering an ethnically diverse city, and there wasn’t a lot of ethnic diversity in our newsroom.” But reporters did try to reflect what was going on in the city.

The Richmond-San Rafael Bridge spans San Francisco Bay, connecting Contra Costa and Marin counties.

(Josh Edelson / For The Times)

As the 21st century dawned, the West County Times, the lone paper still covering Richmond vigorously, was facing a menacing economic shift: the rise of the internet. Advertising dollars — long the financial mainstay of traditional newspapers — moved online, budgets dwindled, and soon there were almost no reporters left to cover Richmond on a daily basis.

Meanwhile, life in Richmond was entering a dark period. The city’s better-paying manufacturing and industrial jobs were evaporating because of economic shifts, spawning an exodus of middle-class earners to the suburbs.

Chevron, which had long been one of the biggest influences on local politics, stayed. But as concerns mounted about the effects of its refinery on air quality, progressive candidates began organizing to counter the weight of the oil company.

The Richmond Standard, funded by Chevron, has been conspicuously silent when it comes to hard-hitting reporting on the company’s refinery.

(Josh Edelson / For The Times)

By 2010, candidates backed by the Richmond Progressive Alliance had pressed the company to contribute more fees to the city to compensate for environmental damage. And then came the disaster of August 2012, when a corroded pipe at the refinery sprung a leak, igniting a series of fiery explosions that shrouded the East Bay in choking black smoke. More than 100,000 people were ordered to shelter in place, with windows and doors sealed shut, and thousands sought medical treatment after inhaling toxic air.

The episode set off a wave of activism that included investigations into Chevron’s operating practices. In August 2013, Chevron agreed to plead no contest to criminal charges stemming from the fire and pay $2 million in fines.

Five months later, on Jan. 23, 2014, Chevron launched the Standard.

“We think it’s good for us to have a conversation with Richmond on important issues, and we also think there are a lot of good stories in this city that don’t get told every day,” the company wrote to readers in announcing the news site.

Progressives were alarmed: The entity that in their eyes most needed watchdogging was now a leading source of local coverage.

Tina Szpicek rallies in support of a November ballot measure that would levy a new tax on Richmond’s Chevron refinery.

(Josh Edelson / For The Times)

Still there was now a reporter roaming the neighborhoods, reporting on a new baseball field, a burglary, local businesses and even some local politics.

In June, while the Standard ignored the City Council’s vote on taxing the refinery, it did cover a Little League triumph, a shooting that left two people dead and the schedule of movies to be screened this summer at “Movies in the Park.”

Ross Allen, a spokesperson for Chevron, said the community didn’t need the Standard to cover the council’s vote — it was a big enough event that it received ample coverage in mainstream California publications.

He added, however, that Chevron opposes the proposed tax, and that “we will have coverage on the reasons why that is a terrible idea for Richmond in the Standard. We’ll have it everywhere.”

The Times interviewed Richmond residents in June to gauge whether the long absence of a local newspaper mattered in their lives. Many said they were unaware of Richmond’s news media history, but in interview after interview stressed their hunger for news about their city.

Juan Alfredo, 27, recently moved to Richmond from Guatemala after a stopover in Los Angeles. He paused to chat while walking his little white poodle in the city’s Miller/Knox Regional Shoreline Park. Across the sparkling waters of the bay, the San Francisco skyline and misty green hills of Marin County rose in the distance.

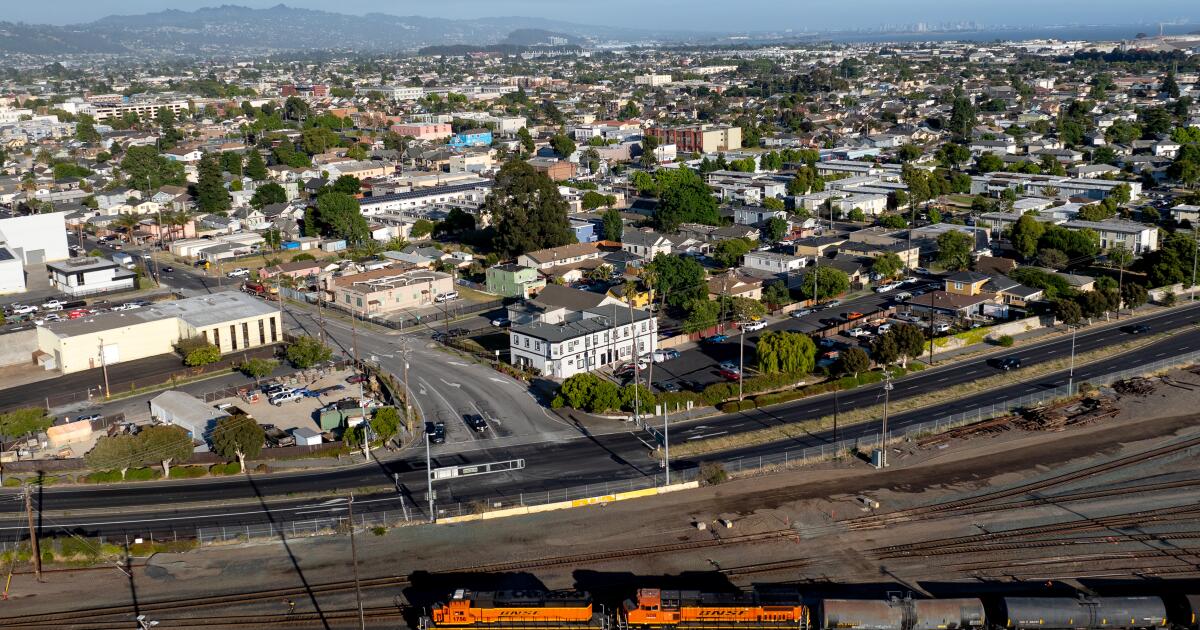

Richmond is one of many smaller working-class cities that saw its local newspapers buckle as print advertising revenue and paid circulation dropped.

(Josh Edelson / For The Times)

Alfredo said that he loves Richmond’s physical beauty, but that his new home struggles with some quality-of-life issues, including trash and messed-up streets. And he has no idea where to turn for information about what is going on in the city.

A few miles away, Elaina Jones, who moved from nearby Orinda last year, said she enjoys the community in the Marina Bay neighborhood. But she said she has little sense of what’s happening in the rest of the city. What she does know, she learns not from local media but from talking to her older neighbors.

Still, she plans to vote in the local elections in November — and said to do so she needs to figure out what’s going on.

One of her would-be representatives, City Council candidate Sue Wilson, said the lack of a local newspaper means candidates often work to reach voters one-on-one, by going to their doors.

Lots of residents are in the dark about who’s running for office and their positions on issues. That may be one reason, some officials said, that voter turnout in local elections is abysmal.

Wilson said Richmond’s tumultuous politics often make her think, “This seems like the sort of thing that would be in the newspaper.”

She paused. “But then there is no newspaper.”

The journalists at Richmondside hope to do their part to change that. On June 25, the site went live with what they hope will be dynamic coverage.

Richmondside is the latest offshoot of the Cityside Journalism Initiative, a nonprofit online news platform launched by journalists looking to reinvigorate local news coverage in the Bay Area. The effort is funded through grants and reader donations.

Surveys done by Richmondside, a new online news venture, found residents want “the rest of the world to know there are many positive stories” in their city.

(Josh Edelson / For The Times)

Richmondside’s new editor, Kari Hulac, said the publication would have two full-time staffers and two interns, as well as editorial support from across the organization and contributions from freelancers. She said readers can look forward to air quality coverage, as well as stories on neighborhood issues, small businesses and public safety.

For Hulac, a veteran Bay Area journalist, the launch represents a welcome second chance to be involved in local news.

“I’ve locked the door on a newsroom,” she recalled of shutting a news bureau in Tracy. “I put the handwritten note on the door: ‘This office is closed permanently.’”

“If you had told me, I don’t know, a year ago, that I would be back in the Bay Area working in a local newsroom again, I never in a million years would have believed it,” she said.

Business

How our AI bots are ignoring their programming and giving hackers superpowers

Welcome to the age of AI hacking, in which the right prompts make amateurs into master hackers.

A group of cybercriminals recently used off-the-shelf artificial intelligence chatbots to steal data on nearly 200 million taxpayers. The bots provided the code and ready-to-execute plans to bypass firewalls.

Although they were explicitly programmed to refuse to help hackers, the bots were duped into abetting the cybercrime.

According to a recent report from Israeli cybersecurity firm Gambit Security, hackers last month used Claude, the chatbot from Anthropic, to steal 150 gigabytes of data from Mexican government agencies.

Claude initially refused to cooperate with the hacking attempts and even denied requests to cover the hackers’ digital tracks, the experts who discovered the breach said. The group pummelled the bot with more than 1,000 prompts to bypass the safeguards and convince Claude they were allowed to test the system for vulnerabilities.

AI companies have been trying to create unbreakable chains on their AI models to restrain them from helping do things such as generating child sexual content or aiding in sourcing and creating weapons. They hire entire teams to try to break their own chatbots before someone else does.

But in this case, hackers continuously prompted Claude in creative ways and were able to “jailbreak” the chatbot to assist them. When they encountered problems with Claude, the hackers used OpenAI’s ChatGPT for data analysis and to learn which credentials were required to move through the system undetected.

The group used AI to find and exploit vulnerabilities, bypass defences, create backdoors and analyze data along the way to gain control of the systems before they stole 195 million identities from nine Mexican government systems, including tax records, vehicle registration as well as birth and property details.

AI “doesn’t sleep,” Curtis Simpson, chief executive of Gambit Security, said in a blog post. “It collapses the cost of sophistication to near zero.”

“No amount of prevention investment would have made this attack impossible,” he said.

Anthropic did not respond to a request for comment. It told Bloomberg that it had banned the accounts involved and disrupted their activity after an investigation.

OpenAI said it is aware of the attack campaign carried out using Anthropic’s models against the Mexican government agencies.

“We also identified other attempts by the adversary to use our models for activities that violate our usage policies; our models refused to comply with these attempts,” an OpenAI spokesperson said in a statement. “We have banned the accounts used by this adversary and value the outreach from Gambit Security.”

Instances of generative AI-assisted hacking are on the rise, and the threat of cyberattacks from bots acting on their own is no longer science fiction. With AI doing their bidding, novices can cause damage in moments, while experienced hackers can launch many more sophisticated attacks with much less effort.

Earlier this year, Amazon discovered that a low-skilled hacker used commercially available AI to breach 600 firewalls. Another took control of thousands of DJI robot vacuums with help from Claude, and was able to access live video feed, audio and floor plans of strangers.

“The kinds of things we’re seeing today are only the early signs of the kinds of things that AIs will be able to do in a few years,” said Nikola Jurkovic, an expert working on reducing risks from advanced AI. “So we need to urgently prepare.”

Late last year, Anthropic warned that society has reached an “inflection point” in AI use in cybersecurity after disrupting what the company said was a Chinese state-sponsored espionage campaign that used Claude to infiltrate 30 global targets, including financial institutions and government agencies.

Generative AI also has been used to extort companies, create realistic online profiles by North Korean operatives to secure jobs in U.S. Fortune 500 companies, run romance scams and operate a network of Russian propaganda accounts.

Over the last few years, AI models have gone from being able to manage tasks lasting only a few seconds to today’s AI agents working autonomously for many hours. AI’s capability to complete long tasks is doubling every seven months.

“We just don’t actually know what is the upper limit of AI’s capability, because no one’s made benchmarks that are difficult enough so the AI can’t do them,” said Jurkovic, who works at METR, a nonprofit that measures AI system capabilities to cause catastrophic harm to society.

So far, the most common use of AI for hacking has been social engineering. Large language models are used to write convincing emails to dupe people out of their money, causing an eight-fold increase in complaints from older Americans as they lost $4.9 billion in online fraud in 2025.

“The messages used to elicit a click from the target can now be generated on a per-user basis more efficiently and with fewer tell-tale signs of phishing,” such as grammatical and spelling errors, said Cliff Neuman, an associate professor of computer science at USC.

AI companies have been responding using AI to detect attacks, audit code and patch vulnerabilities.

“Ultimately, the big imbalance stems from the need of the good-actors to be secure all the time, and of the bad-actors to be right only once,” Neuman said.

The stakes around AI are rising as it infiltrates every aspect of the economy. Many are concerned that there is insufficient understanding of how to ensure it cannot be misused by bad actors or nudged to go rogue.

Even those at the top of the industry have warned users about the potential misuse of AI.

Dario Amodei, the CEO of Anthropic, has long advocated that the AI systems being built are unpredictable and difficult to control. These AIs have shown behaviors as varied as deception and blackmail, to scheming and cheating by hacking software.

Still, major AI companies — OpenAI, Anthropic, xAI, and Google — signed contracts with the U.S. government to use their AIs in military operations.

This last week, the Pentagon directed federal agencies to phase out Claude after the company refused to back down on its demand that it wouldn’t allow its AI to be used for mass domestic surveillance and fully autonomous weapons.

“The AI systems of today are nowhere near reliable enough to make fully autonomous weapons,” Amodei told CBS News.

Business

iPic movie theater chain files for bankruptcy

The iPic dine-in movie theater chain has filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection and intends to pursue a sale of its assets, citing the difficult post-pandemic theatrical market.

The Boca Raton, Fla.-based company has 13 locations across the U.S., including in Pasadena and Westwood, according to a Feb. 25 filing in U.S. Bankruptcy Court in the Southern District of Florida, West Palm Beach division.

As part of the bankruptcy process, the Pasadena and Westwood theaters will be permanently closed, according to WARN Act notices filed with the state of California’s Employment Development Department.

The company came to its conclusion after “exploring a range of possible alternatives,” iPic Chief Executive Patrick Quinn said in a statement.

“We are committed to continuing our business operations with minimal impact throughout the process and will endeavor to serve our customers with the high standard of care they have come to expect from us,” he said.

The company will keep its current management to maintain day-to-day operations while it goes through the bankruptcy process, iPic said in the statement. The last day of employment for workers in its Pasadena and Westwood locations is April 28, according to a state WARN Act notice. The chain has 1,300 full- and part-time employees, with 193 workers in California.

The theatrical business, including the exhibition industry, still has not recovered from the pandemic’s effect on consumer behavior. Last year, overall box office revenue in the U.S. and Canada totaled about $8.8 billion, up just 1.6% compared with 2024. Even more troubling is that industry revenue in 2025 was down 22.1% compared with pre-pandemic 2019’s totals.

IPic noted those trends in its bankruptcy filing, describing the changes in consumer behavior as “lasting” and blaming the rise of streaming for “fundamentally” altering the movie theater business.

“These industry shifts have directly reduced box office revenues and related ancillary revenues, including food and beverage sales,” the company stated in its bankruptcy filing.

IPic also attributed its decision to rising rents and labor costs.

The company estimated it owed about $141,000 in taxes and about $2.7 million in total unsecured claims. The company’s assets were valued at about $155.3 million, the majority of which coming from theater equipment and furniture. Its liabilities totaled $113.9 million.

The chain had previously filed for bankruptcy protection in 2019.

Business

Startup Varda Space Industries snags former Mattel plant in El Segundo

In an expansion of its business of processing pharmaceuticals in Earth’s orbit, Varda Space Industries is renting a large El Segundo plant where toy manufacturer Mattel used to design Hot Wheels and Barbie dolls.

The plant in El Segundo’s aerospace corridor will be an extension of Varda Space Industries’ headquarters in a much smaller building on nearby Aviation Boulevard.

Varda will occupy a 205,443-square-foot industrial and office campus at 2031 E. Mariposa Ave., which will give it additional capacity to manufacture spacecraft at scale, the company said.

Originally built in the 1940s as an aircraft facility, the complex has a history as part of aerospace and defense industries that have long shaped the South Bay and is near a host of major defense and space contractors. It is also close to Los Angeles Air Force Base, headquarters to the Space Systems Command.

Workers test AstroForge’s Odin asteroid probe, which was lost in space after launch this year.

(Varda Space Industries)

Varda is one of a new generation of aerospace startups that have flourished in Southern California and the South Bay over the last several years, particularly in El Segundo, often with ties to SpaceX.

Elon Musk’s company, founded in 2002 in El Segundo, has revolutionized the industry with reusable rockets that have radically lowered the cost of lifting payloads into space. Though it has moved its headquarters to Texas, SpaceX retains large-scale operations in Hawthorne.

Varda co-founder and Chief Executive Will Bruey is a former SpaceX avionics engineer, and the company’s spacecraft are launched on SpaceX’s workhorse Falcon 9 rockets from Vandenberg Space Force Base in Santa Barbara County.

Varda makes automated labs that look like cylindrical desktop speakers, which it sends into orbit in capsules and satellite platforms it also builds. There, in microgravity, the miniature labs grow molecular crystals that are purer than those produced in Earth’s gravity for use in pharmaceuticals.

It has contracts with drug companies and also the military, which tests technology at hypersonic speeds as the capsules return to Earth.

Its fifth capsule was launched in November and returned to Earth in late January; its next mission is set in the coming weeks. Varda has more than 10 missions scheduled on Falcon 9s through 2028.

For the last several decades, the Mariposa Avenue property served as the research and development center for Mattel Toys. El Segundo has also long been a center for the toy industry as companies like to set up shop in the shadow of Mattel.

The Mattel facility “has always been an exceptional property with a legacy tied to aerospace innovation, and leasing to Varda Space Industries feels like a natural continuation of that story,” said Michael Woods, a partner at GPI Cos., which owns the property.

“We are proud to support a company that is genuinely pushing the boundaries of what’s possible, and are excited to watch Varda grow and thrive here in El Segundo,” Woods said.

As one of the country’s most active hubs of aerospace and defense innovation, El Segundo has seen its industrial property vacancy fall to 3.4% on demand from space companies, government contractors and technology startups, real estate brokerage CBRE said.

Successful startups often have to leave the neighborhood when they want to expand, real estate broker Bob Haley of CBRE said. The 9-acre Mattel facility was big enough to keep Varda in the city.

Last year, Varda subleased about 55,000 square feet of lab space from alternative protein company Beyond Meat at 888 Douglas St. in El Segundo, which it started moving into in June.

Varda will get the keys to its new building in December and spend four to eight months building production and assembly facilities as it ramps up operations. By the end of next year, it expects to have constructed 10 more spacecraft.

In the future, Varda could consolidate offices there, given its size. Currently, though, the plan is to retain all properties, creating a campus of three buildings within a mile of one another that are served by the company’s transportation services, Chief Operating Officer Jonathan Barr said.

“We already have Varda-branded shuttles running up and down Aviation Boulevard,” he said.

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoExclusive: DeepSeek withholds latest AI model from US chipmakers including Nvidia, sources say

-

Wisconsin4 days ago

Wisconsin4 days agoSetting sail on iceboats across a frozen lake in Wisconsin

-

Massachusetts1 week ago

Massachusetts1 week agoMother and daughter injured in Taunton house explosion

-

Maryland5 days ago

Maryland5 days agoAM showers Sunday in Maryland

-

Massachusetts3 days ago

Massachusetts3 days agoMassachusetts man awaits word from family in Iran after attacks

-

Florida5 days ago

Florida5 days agoFlorida man rescued after being stuck in shoulder-deep mud for days

-

Denver, CO1 week ago

Denver, CO1 week ago10 acres charred, 5 injured in Thornton grass fire, evacuation orders lifted

-

Oregon6 days ago

Oregon6 days ago2026 OSAA Oregon Wrestling State Championship Results And Brackets – FloWrestling