Business

How second-generation owners of 99 Ranch are turning the Asian supermarket into a national powerhouse

For many Asian Americans across California, 99 Ranch is much more than just a grocery store. It’s a pilgrimage. When I was a child growing up in the San Fernando Valley in the 1990s, my Taiwanese parents would drive over an hour east to the San Gabriel Valley every single weekend just to shop at 99 Ranch.

They’d load up on squirming live shrimp, jadeite bundles of water spinach and fat, oblong lotus roots. For them, it was a refuge where they could indulge in the flavors of their native Taiwan. While there were plenty of Asian supermarkets to choose from in the ’90s, we always went to 99 Ranch because they had the largest and best selection of goods. Right before we hit the cashier, my brother and I would each get a singular pick of something sweet. I’d go for a Taiwanese-style flan. My brother liked the chocolate-filled koala-shaped cookies from Japan.

“I loved the White Rabbit candy,” says Jonson Chen, citing a sweet milk candy from Shanghai. Mustached with slicked-back hair, Chen is the chairman of 99 Ranch Market. I meet him and his sister, Alice Chen, the company’s chief executive, inside their newest store location in Eastvale, a 50,000-square-foot compound including a warehouse and a food hall that is set to open next month. The Chen siblings represent a new generation of leadership at the nearly 40-year-old grocery chain, helming its expansion across the United States.

The first 99 Ranch was opened in 1984 in Westminster by Jonson and Alice’s father, Roger Chen, a Taiwanese immigrant from the western city of Taichung. Headquartered in Buena Park with 58 stores in 11 states, it is now one of the largest Asian supermarket chains in America. While pan-Asian in its offerings, the company caters heavily to ethnically Chinese communities, whose preferences and cultural habits have shaped what they stock in their stores. The “ranch” in 99 Ranch means freshness (“as if straight from a ranch,” Alice says) and the “99,” in Mandarin Chinese pronounced jiu jiu, is a homophone for longevity. “The double meaning is 99%. It’s almost perfect, but not quite,” Alice, fresh-faced with a pristine white blouse, says. “We’re always trying to be better. It’s very Asian. No one is 100%.”

Live fish tanks are a feature of 99 Ranch markets and a signal of freshness for many families who immigrated from countries where wet markets are staples.

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times)

At the 99 Ranch in Eastvale, a fish counter worker holds a live rockfish. The 99 Ranch chain has more than 7,000 employees — 82% of them bilingual — and a team of buyers keeping tabs on what shoppers are craving.

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times)

Shoppers’ demands have changed over the years, but certain elements at 99 Ranch stores — like the live fish tanks — have stayed the same.

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times)

Like many children of the Chinese-speaking diaspora in California, Alice and Jonson grew up with fond memories of the grocery chain. But unlike the rest of us, they had a front-row seat. The siblings spent many weekends ensconced behind the customer service counter at the store “bored out of our minds,” Jonson jokes. But he still remembers with fondness the retrofitted pickup trucks with steel tanks that pulled up to his parents’ grocery stores in the early morning.

“You’d look inside and it would be dark. But it was full of catfish,” Jonson tells me. Back then, workers would drag the fish out with nets, plop them into a trash can, and wheel the trash can into the store, where the fish would be deposited into bubbling, iridescent fish tanks for customers to pick and choose from.

Live fish tanks are a distinct feature of Asian grocery stores — a guarantee of freshness and a prerequisite for many families who immigrated from countries where wet markets are staples. “There are hundreds of varieties of fish, but it was a matter of figuring out what was available live and what people wanted to see,” Jonson says.

On the logistics end, the company had to figure out a lot from scratch: how to transport live fish into the store, import food from Asia, and create a network of farms that could grow hard-to-find vegetables like water spinach and bitter melon that their consumers wanted and craved. “Initially it was just [Roger] calling up like random suppliers in Taiwan asking if they would ship to America,” Alice says.

They eventually figured it out: Today, most of the grocery chain’s produce is grown on specialty farms across the United States and Mexico. They have a network of over 7,000 employees — 82% of them bilingual — and a team of buyers keeping close tabs on what people are craving. These days, those trends include Filipino ingredients, skewers and spicy, tongue-numbing Sichuan flavors. “We are a part of the Asian community. We hire from the community. The customers are also the workers,” Jonson tells me.

An assortment of Thai bananas, left, and Japanese mountain yams called nagaimo, right, are among the fresh produce available at the 99 Ranch in Eastvale, which opened in February.

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times)

The sprawling produce area at the latest 99 Ranch. A new food hall will open at this location in August.

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times)

Now, 99 Ranch was not the first Asian grocery store in Southern California. In the late ’70s, there were already a few in the San Gabriel Valley. But the chain stood out because of its expansion strategy. “They did their market research to determine where there were communities needing to be served,” says David R. Chan, a Los Angeles food blogger and retired tax lawyer who has eaten at thousands of Chinese restaurants in America since the 1950s.

The company’s third location at a Rowland Heights shopping plaza on Nogales Street, which opened in 1989, marked a turning point for the brand. Chan, who visited the supermarket when it first opened and in subsequent years, remembers a progressive increase of Chinese restaurants that popped up in the plaza and the surrounding neighborhood after the grocery store’s opening.

“Chen had a broader real estate vision to develop Asian shopping centers anchored by a supermarket, as opposed to merely operating a supermarket and perhaps adding additional locations,” Chan says. The eighth (though technically the seventh because they don’t count No. 4 — an unlucky number in Chinese culture) location in a former drive-in movie theater in San Gabriel, opened in 1991, became another anchor and is arguably the chain’s most iconic location today. “Back then, the areas of Arcadia, Alhambra, Rosemead, Temple City, San Gabriel were starting to be known as Little Taipei,” Jonson says. “That store was able to create a Chinese community.”

As second-generation owners, Jonson and Alice Chen keep up with the evolution of Asian communities and their shopping habits. There’s not as big of a demand for butchery; shoppers would rather have their meat pre-sliced and packaged.

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times)

At a cafe inside 99 Ranch, you can buy freshly made egg waffle cakes.

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times)

Today, Jonson focuses on the brand’s real estate expansion strategy, keeping close tabs on where Chinese-speaking communities are spreading across America. Since 2020, 99 Ranch has added seven new stores to the chain.

“99 Ranch Market is the gold standard for market research as to where Chinese communities are showing up. And this is not just in California, but all over the country,” says Chan, who keeps a database of Chinese restaurant openings all over the U.S.

As children, neither Jonson nor Alice anticipated taking over their dad’s company. Their father never pressured them to work for him, but always kept the door open in case they showed interest. They tell me that while they grew up with the grocery store, it took a while for them to realize just how big the brand had gotten. “We just told people he was in the import and export business,” Alice says. It wasn’t until Alice wrote a college thesis on the family company and had to interview her father that the penny dropped. “He just never shared anything with us prior,” she says.

A store clerk adds more fresh sweet chiles to a display pile at the new Eastvale store, which is 51,000 square feet and includes a warehouse.

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times)

Today, as the second-generation owners, Jonson and Alice’s job is to keep up with the evolution of Asian communities in America, which, they point out, have different shopping habits than previous generations. Generally speaking, there’s a greater demand for frozen products and prepared foods. There’s not as big of a demand for butchery; people today would rather have their meat pre-sliced and packaged.

Yet certain elements — like the live fish tanks — have stayed the same (though the retrofitted pickups have mostly been phased out; there are now dedicated live-haul trucks for the fish).

The siblings take me on a stroll through the aisles of the new Eastvale market, which opened in February this year. We walk up to a tank dedicated to just spot prawns — fat, reddish brown and almost translucent underneath the fluorescent overhead lights. Jonson notices me marveling at them. “They’re from Newport Beach’s Dory Fleet Fish Market. People will go there every Saturday morning. So you can go there and wait in line. They are usually sold out within the first hour,” he says. “Or you can just go to a 99 Ranch.”

Clarissa Wei is a writer and cookbook author. Her forthcoming book, “Made in Taiwan: Recipes and Stories From the Island Nation” (SS Element), will publish in the fall.

Business

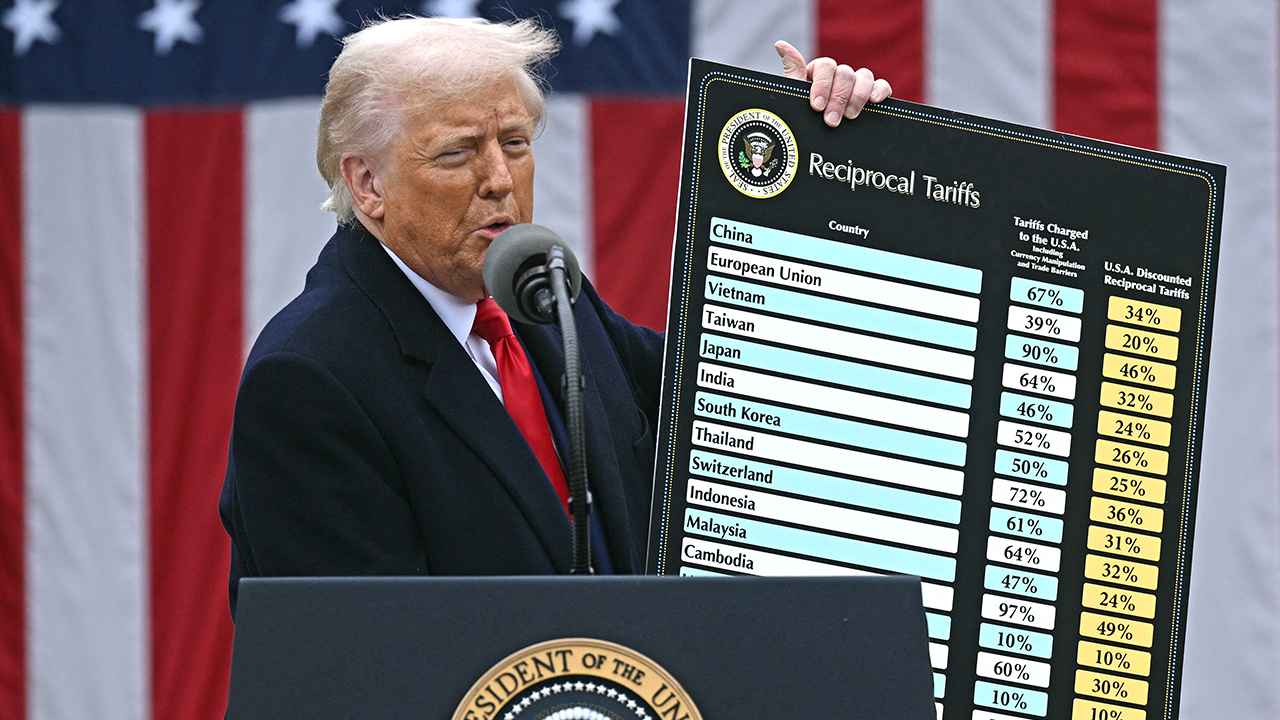

Trump’s Tariffs Hit Garment Makers in Bangladesh and Sri Lanka Hard

Through Covid, political chaos, and economic disarray, Sri Lanka and Bangladesh kept one industry central to their hopes of prosperity afloat: the manufacturing of ready-made garments, with the United States as their main market.

Then came President Trump’s tariffs.

The two countries are reeling after Sri Lanka was hit with 44 percent tariffs and Bangladesh subjected to 37 percent levies. Officials in both countries scrambled to contain panic among business leaders, who worried that they may no longer be able to compete with bigger manufacturing powers, and that their orders could shift to places with lower tariffs and greater industrial muscle.

“We will have to write our obituary notice,” said Tuli Cooray, a consultant at the Joint Apparel Association Forum of Sri Lanka, an industry association. “Forty-four percent is no joke.”

The Trump administration’s tariffs has hit countries at the heart of the global apparel industry especially hard. An analysis by William Blair, an equity research firm, showed that the countries that produce 85 percent of U.S. apparel imports faced an average tariff of 32 percent.

Targeting the manufacturers not only upends the economies of these nations, but also adds to the burden of U.S. companies, analysts warned. William Blair said merchandise costs could go up by about 30 percent and American consumers may ultimately feel the pinch.

Bangladesh sends more than $7bn of clothing to the U.S. every year. The country’s garment manufacturing industry makes up 80 percent of its total exports and employs more than four million people, mostly women. Bangladesh has one of the highest female work force participation rates in the region, which has helped lift a large section of the population out of poverty.

The garment industry is crucial, as the country tries to stabilize its economy after widespread protests and violence last year toppled its autocratic leader.

“Just as the world economy was starting to recover and we were seeing our sales in the U.S. increase, this kind of decision — a trade war, or a tariff war — has now posed a new challenge and uncertainty,” said Mohiuddin Rubel, a former director of the Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association.

“There are many garment factories in Bangladesh that work solely for the U.S. market — some with 80 percent, some even 100 percent. These factories have made large investments just for US orders,” he added. “This decision will put such businesses in danger.”

In Sri Lanka, the garment industry employs more than 350,000 people, producing apparel for companies such as Nike and Victoria’s Secret. Garments make up about half of the country’s total exports, and the vast majority go to the U.S..

After the country’s economy crashed in 2022, it has been slowly stabilizing with the help of aid from neighbors like India and a bailout from the International Monetary Fund.

“We are trying to see if there is space for reduction before implementation on April 9 through discussions, especially considering the difficult situation we are in,” said Anil Jayantha Fernando, Sri Lanka’s deputy minister for economic development.

Business

Column: GOP thinks the court orders they used against Biden should be outlawed — because they now target Trump

The old political adage that “where you stand depends upon where you sit” has been getting aired out in Washington.

Republicans and conservatives used to celebrate judges’ issuance of nationwide court injunctions to block Biden policies or progressive government programs.

Now that nationwide court injunctions are being used to block Trump policies, however, onetime fans of the practice have decided that it’s unconstitutional and illegal and needs to be outlawed.

National injunctions are equal opportunity offenders.

— Law professors Nicholas Bagley and Samuel Bray

“When a single district court judge halts a law or policy across the entire country,” Rep. Jim Jordan (R-Ohio), chairman of the House Judiciary Committee, wrote his colleagues on Monday, “it can undermine the federal policymaking process and erode the ability of popularly elected officials to serve their constituents.”

That’s not untrue. But I couldn’t find evidence that Jordan ever made this point before Trump came into office. I asked his committee staff to identify any such reference, but haven’t heard back.

The issue of nationwide injunctions — in which federal judges apply their rulings beyond the specific plaintiffs who have brought suits in their courthouses — dovetails with another widely decried abuse of the judicial process. That’s “judge-shopping,” through which litigants connive to bring their cases before judges they assume will rule in their favor, typically by filing lawsuits in judicial divisions staffed by only a single judge whose predilections are known.

The combination of these schemes allowed conservative judges in remote federal courthouses to block major policy initiatives by President Biden, such as his efforts to enact student debt relief.

Judges also took aim at longer-standing progressive programs, as when Judge Reed O’Connor of Fort Worth, a George W. Bush appointee, declared the entire Affordable Care Act unconstitutional in 2018. The Supreme Court decisively slapped O’Connor down with a 7-2 ruling upholding the ACA’s constitutionality in 2021.

Ignoring the Supreme Court’s signal, O’Connor subsequently ruled that the ACA’s provision for no-cost preventive services was also unconstitutional. Parts of that ruling were overturned by an appeals court, but parts are now before the Supreme Court, which will hear the case this year.

Then there’s federal Judge Matthew Kacsmaryk of Amarillo, Texas, who last year overturned the Food and Drug Administration’s long-standing approval of the abortion drug mifepristone. The Supreme Court unanimously threw out that case in June.

During the Biden administration, a serial abuser of the judge-shopping process was Texas Atty. Gen. Ken Paxton.

According to a 2023 analysis by Steve Vladeck of Georgetown law school, in the first two years of Biden’s term, Texas filed 29 challenges to Biden initiatives. Not a single case was filed in Austin, where the attorney general’s office is but where a lawsuit had only a 50-50 chance of drawing a Republican judge. Nor were any cases filed in the big cities of Houston, Dallas, San Antonio or El Paso.

Instead, they were filed in the court’s single-judge Victoria, Midland and Galveston divisions, where the state had a 100% chance of drawing a judge appointed by Trump; in Amarillo, where the chance was 95%; and Lubbock, where it was 67%.

Republicans and conservatives raised no fuss about judge-shopping and nationwide injunctions when they targeted Biden or Obama policies.

But now they’re screaming bloody murder about “rogue judges,” suggesting the judges are exceeding their authority simply because they have ruled against Trump and applied their rulings nationwide. Rep. Darrell Issa (R-Bonsall), for example, has introduced what he calls the No Rogue Rulings Act, which would bar nationwide injunctions.

It’s true that “national injunctions are equal opportunity offenders,” as Nicholas Bagley of the University of Michigan and Samuel Bray of Notre Dame wrote in 2018. “Before courts entered national injunctions against the Trump administration, they used them to thwart the Obama administration’s rule for overtime pay and its signature immigration policy, Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals.”

They were referring to injunctions issued against President Trump during his first term, but the pace has quickened during the current term.

That’s not necessarily because judges have become more roguish, but because Trump has given them more to ponder. In his first 65 days in office, Vladeck reported in a recent post, Trump issued 100 executive orders, besting the record set by Franklin D. Roosevelt in his first hundred days, when he issued 99. Biden issued only 37 executive orders in his first 65 days, and Trump only 17 in the same span during his first term.

Those orders and other Trump actions have triggered more than 67 lawsuits seeking preliminary injunctions or temporary restraining orders, Vladeck calculated; federal judges have granted some relief in 46 of those cases.

There are some important differences from the litigation style of Biden’s partisan opponents, however. For one thing, Trump’s challengers haven’t engaged in judge-shopping. With one short-lived exception, none of the 67 cases was filed in a single-judge division.

The majority of cases in Vladeck’s database were filed in courts where the chance of drawing a specific judge was less than 15%. The cases were filed in 14 different courts, with a plurality (31 of the 67) filed in the Washington, D.C., judicial district — not a surprise, since that’s the customary venue for lawsuits challenging a government action.

Judge-shopping isn’t illegal, but even conservatives have found it to be sleazy. Last year, the Judicial Council of the United States, a policy guidance body headed by Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr., stated that any lawsuit seeking a nationwide or statewide injunction against the government should be randomly assigned to a judge in the federal district where it’s filed.

The guidance, which wasn’t binding, won wide support in the federal judiciary — except in the Northern District of Texas, home to the Amarillo, Fort Worth and Lubbock divisions. There the chief judge said he wouldn’t agree.

During a recent appearance on Fox News, Jordan was asked by the conservative anchor Mark Levin whether Democrats are “forum-shopping” to get cases before judges appointed by Democratic presidents. Jordan assented enthusiastically, grousing: “You have a judge in Timbuktu, California, who can do some order and some injunction” to obstruct Trump.

Jordan’s reference was to U.S. District Judge William Alsup, who on Feb, 28 issued a temporary restraining order requiring Trump to cease the wholesale firing of federal employees at six agencies and return the workers to their jobs.

A couple of things about that. First, I’ve been to the real Timbuktu, which is a desert outpost in Mali. San Francisco is possibly the one city in America least likely to be mistaken for that Timbuktu. San Francisco is a city of more than 800,000 residents, nestled within a metropolitan area of 7.5 million. Amarillo, where Kacsmaryk presides, is a community of about 202,000, within a metro area of 270,000.

As for judge-shopping, Jordan might want to bring his concerns to the Trump administration itself. On March 27, the administration filed a federal lawsuit to terminate collective bargaining agreements reached by eight federal agencies.

The White House filed the case not in northern Virginia, the District of Columbia or any other jurisdiction where large numbers of affected federal workers probably live and work, but in Waco, Texas, a courthouse with a single federal judge, a Trump appointee.

“It’s the height of irony that the only judge-shopping we’re seeing in Trump-related cases is … from Trump,” Vladeck observes.

One might be tempted to give the Republicans the benefit of the doubt on their crusade against “rogue” judges, except for a couple of factors. One is their silence about nationwide injunctions when the results meshed with their anti-Biden ideology.

The other is that their objections to nationwide injunctions has been couched within a broader attack on the independent judiciary. Republicans have advocated impeaching judges for rulings against Trump, a stance that drew a rare public pushback from Chief Justice Roberts.

House Speaker Mike Johnson (R-La.) also raised the prospect of shutting down courts that flout Republican initiatives. “We can eliminate an entire district court. We have power of funding over the courts and all these other things,” he told reporters last week. “But desperate times call for desperate measures, and Congress is going to act.”

All that makes their position look less like a principled stand against judicial activism, and more like partisan hypocrisy.

Business

Auto Tariffs Take Effect, Putting Pressure on New Car Prices

Tariffs on imported vehicles took effect Thursday, a policy that President Trump said would spur investments and jobs in the United States but that analysts say will raise new car prices by thousands of dollars.

The 25 percent duty applies to all cars assembled outside the United States. Starting May 3, the tariff will also apply to imported auto parts, which will add to the cost of cars assembled domestically as well as auto repairs.

There will be a partial exemption for cars made in Mexico or Canada that meet the terms of free trade agreements with those countries. Carmakers will not have to pay duties on parts like engines, transmissions or batteries that were made in the United States and later installed in cars in Mexican or Canadian factories.

That provision will reduce the impact on vehicles like the Chevrolet Equinox electric vehicle, which is assembled in Mexico but includes a battery pack and other components made in the United States. General Motors will pay a tariff only on the portion of the car made abroad.

At the same time, the duty on parts will raise the cost of cars made in Michigan, Tennessee, Ohio or other states. That is because most cars rolling out of U.S. factories contain components made abroad, often amounting to more than half the cost of the vehicle.

About 90 percent of the value of some Mercedes-Benz cars made in Alabama, for example, is in engines and transmissions that are imported from Europe, according to data compiled by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration.

The impact of the tariffs on individual vehicles will vary widely. Cars like the Tesla Model Y, made in Texas and California, or Honda Passport, made in Alabama, have high percentages of U.S.-made parts and will pay lower tariffs.

Tariffs will be highest on cars manufactured abroad, like the Toyota Prius made in Japan or Porsche sports cars made in Germany.

Even people who don’t buy new cars will be hit by the tariffs because they will pay more for parts like tires, brake pads and oil filters.

Michael Holmes, co-chief executive of Virginia Tire and Auto, a chain of auto repair and maintenance shops, said he and his suppliers would initially try to absorb most of the increased cost.

“That’s not sustainable,” Mr. Holmes said. “It’s magical thinking to think businesses won’t pass this on.”

The auto tariffs could also push up prices for used cars over time, analysts said, by increasing demand for those vehicles as new ones become unaffordable for many buyers. Insurance premiums may also rise because repairs will cost more.

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoTrump Is Trying to Gain More Power Over Elections. Is His Effort Legal?

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoWashington Bends to RFK Jr.’s ‘MAHA’ Agenda on Measles, Baby Formula and French Fries

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoCompanies Pull Back From Pride Events as Trump Targets D.E.I.

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoAt least six people killed in Israeli attacks on southern Syria

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoTrump officials planned a military strike over Signal – with a magazine editor on the line

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoThe FBI launched a task force to investigate Tesla attacks

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoNo, Norway and Sweden haven't banned digital transactions

-

Culture1 week ago

Culture1 week agoAnalysing Jamal Musiala’s bizarre corner goal for Germany against Italy