Business

He claims to have saved California homeowners billions. The insurance industry hates him

Insurance industry groups have called it a “bomb-throwing bogus advocacy” group, a “publicity-seeking, dark money front,” and an organization out to protect its own “financial $elf-interest$.”

These are the kinds of attacks that Harvey Rosenfield and Consumer Watchdog, the advocacy group he founded nearly 40 years ago, have come to expect.

But in the last year, as home insurers have stopped writing new policies and retreated from parts of the state prone to wildfire, a new voice has joined the ranks of critics who say Harvey and Co. are making things worse: California’s elected insurance commissioner, Ricardo Lara, whose office has called Consumer Watchdog an entrenched interest group “defending its own piggy bank.”

California Insurance Commissioner Ricardo Lara speaks at a state Capitol news conference in Sacramento.

(Rich Pedroncelli / Associated Press)

If attacking a public advocacy group seems like an odd stance for an elected official, it’s made even odder by the fact that Lara wouldn’t have his job if it weren’t for Consumer Watchdog.

To understand the beef, you need to understand Proposition 103, a California law governing the insurance industry.

The campaign for that ballot measure in 1988 was one of the first missions of Consumer Watchdog, which formed in the wake of Ralph Nader’s success in spurring new consumer regulation.

That proposition, which Rosenfield helped write, enacted some of the most stringent insurance industry regulation in the nation. First, it created the office of an elected insurance commissioner to head the state Department of Insurance. Any time an insurance company seeks to raise prices, Proposition 103 requires that the firm apply to the commissioner for prior approval.

The goal, according to the text of the act, is to provide transparency into the insurance market and prevent insurers from charging “excessive, inadequate or unfairly discriminatory” rates to policyholders.

Nearly 35 years after Proposition 103 went into effect, Californians pay less for auto and home insurance than most Americans, with the state ranking among the bottom half of states for prices in both categories. But insurers say that long processing times for rate increases, among other regulations, have made it difficult to do business in the state as inflation and wildfire risks are on the rise.

One specific criticism of Consumer Watchdog revolves around a unique proviso of Proposition 103. The law allows public groups such as Consumer Watchdog to intervene in an insurance company’s application for a rate increase and argue — alongside the Department of Insurance — for what the ultimate price should be.

When groups such as Consumer Watchdog intervene, Proposition 103 stipulates that they can get paid for their efforts. After paying the intervening groups, insurance companies wind up passing those fees along to consumers. Insurance companies argue that this provides Consumer Watchdog and others a perverse incentive to turn every rate filing into a battle in order to get paid their fees.

“No other state has this kind of public participation and scrutiny built into the regulatory process, which is why Prop 103 is their number one target,” Rosenfield said. “It drives them nuts.”

“It comes down to the money, right?” said Carmen Balber, Consumer Watchdog’s executive director. “Thanks to the intervenor process, consumers pay less for their home and auto insurance than they would otherwise, and the industry has sought to claw back those profits for decades now.”

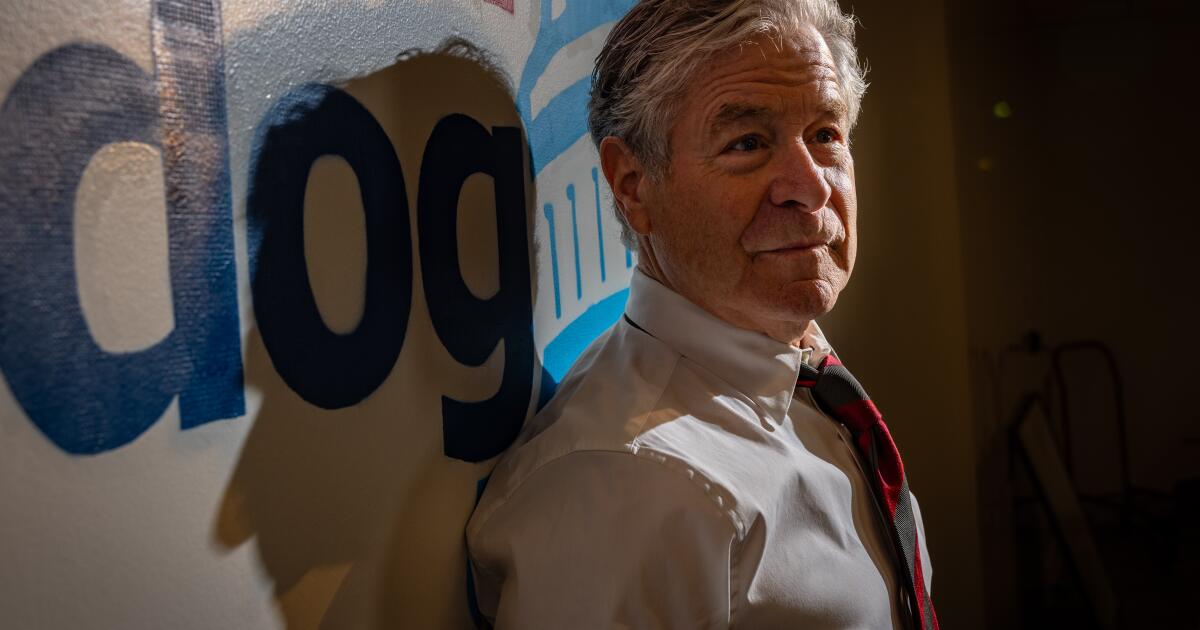

Consumer Watchdog’s Jamie Court, Harvey Rosenfield and Carmen Balber pose for a portrait in their Los Angeles offices Feb. 1.

(Jason Armond / Los Angeles Times)

There has been friction between the insurance industry and consumer groups for decades, but things have recently started to boil over.

The American Property Casualty Insurance Assn., the nation’s largest insurance lobbying group, bankrolled a new website attacking Consumer Watchdog in late 2023. Spokespeople for the Insurance Information Institute and the Personal Insurance Federation of California regularly opine to reporters that Rosenfield, Balber and the group’s president, Jamie Court, are wrenches in the underwriting machinery.

“The industry is going after Consumer Watchdog harder than normal,” said Brian Sullivan, owner and editor of insurance industry publication Risk Information. And the feud between the group and the Department of Insurance keeps escalating. “I have never seen the relationship degrade to the point it’s at now,” Sullivan said.

The industry groups have been pushing for changes in Sacramento and at the Department of Insurance — and at the close of last year’s legislative session, saw some results in the forms of promises to loosen regulations.

Lara, the state’s insurance commissioner, has had a rocky relationship with Consumer Watchdog from the start. After he pledged to not accept campaign funds from insurers in his first run for the office in 2018, a San Diego Union-Tribune investigation revealed that Lara had accepted hundreds of thousands of dollars in campaign contributions from people and companies with ties to the insurance industry. Consumer Watchdog filed a public records request for communications between Lara’s department and the insurance companies linked to the donations, and then sued the commissioner for allegedly failing to respond to the request in full. The group lost its initial lawsuit, but is continuing to fight it in the state Courts of Appeal.

Since then, the group has accused Lara’s office of ramming through rate increases without adequate review or opportunity for public input, and called his plans to change regulations with the goal of bringing more insurers back to the state market a “sham.”

Lara, in turn, noted in a news conference announcing his proposed reforms that “bombastic statements from entrenched interest groups” help no one, and that “one entity can unreasonably prolong rate filings” while “materially benefiting from a process that is meant for broader public participation.”

Michael Soller, Lara’s spokesperson with the department, has been less coy about the “entity” in question. After Consumer Watchdog accused Lara of striking a secret deal with insurance companies in the fall, Soller put out a statement saying that the group’s “cynical claims hide the truth that [it] has earned millions of dollars signing off on rate increases — while denying the reality that insurance has become impossible for some Californians to find at any price.” He added that the group “is turning a blind eye to consumers’ needs while defending its own insurance piggy bank.”

Yes, they’re a big pain, but that’s their job.

— Rep. John Garamendi, describing Consumer Watchdog

While other consumer groups such as United Policyholders and the Consumer Federation of California have taken a more measured approach, Rosenfield has been blunt. “A commissioner more disposed to protect the industry has come along,” Rosenfield said. “Ultimately, there’s accountability for that within our system of democracy.”

“He’s kind of out a little bit on his own on this in terms of opposing what Lara’s doing,” said Brian Sullivan of Risk Information.

Increasingly, Consumer Watchdog is one of the only consumer advocates even participating in the Proposition 103 process. In the early days of the regime, half a dozen or so major consumer groups were willing to enter the fray. But over time, the pool of dedicated groups with the resources to fight long regulatory battles and only get paid months (and sometimes years) after their work begins, has dwindled to a handful. Now state records show that 75% of the time, if there’s an intervening entity in a rate filing, it’s Consumer Watchdog.

This is where the accusation of self-interest comes to bear. Since Rosenfield helped write Proposition 103, he also wrote in the fee mechanism that pays his salary at Consumer Watchdog. According to critics, that amounts to self-dealing at the consumers’ expense.

State records show that over the last two decades, the group has been paid $11.6 million in fees by the state for its interventions in rate filings, or an average of $575,000 each year. Proposition 103 isn’t Consumer Watchdog’s only policy focus, nor is it the group’s only source of revenue. Consumer Watchdog brought in $3.75 million in revenue in 2022 from donations, grants and other sources, according to public filings.

For that $11.6 million Proposition 103 payout, the group has been party to saving consumers $5.51 billion in the last two decades, according to an analysis produced by Consumer Watchdog. In the last five years, Consumer Watchdog says its actions have contributed to $2.1 billion in savings for Californians. The group arrived at these figures by comparing the dollar value of rate increases that insurance companies sought in the last 22 years against the final amount they got when Consumer Watchdog challenged their request.

In the last two years, when Consumer Watchdog intervened in a company’s request to raise its rates, the final result for ratepayers ended up 38% lower than what the companies requested for home insurance, and 29% lower for auto insurance, on average. When Consumer Watchdog didn’t enter the fray, the final amount approved by the state insurance department was only 2-3% lower than what companies requested on average, according to the report.

Soller, the insurance department spokesperson, calls these numbers “deeply flawed.”

“Based on our review, their claims are highly inflated,” Soller wrote in a statement. “They compared the amount originally requested by the insurance company to the amount approved, with no accounting for what the department’s role was in that three-party negotiation.”

In other words, it is impossible to attribute all of those savings to the group’s intervention because state insurance regulators probably would have argued down the companies’ requests on its own.

But the scale of California’s insurance market means even small concessions can have a big effect on ratepayers. If Consumer Watchdog’s interventions contributed 0.3% of those $5.2 billion that insurance rates have been pushed downward, then the group has saved Californians millions more than it’s been paid in fees.

Rep. John Garamendi (D-Walnut Grove), who served as the state’s first and fourth elected insurance commissioner, finds the attempts to discredit Consumer Watchdog disturbing, if not surprising.

Rep. John Garamendi speaks at a meeting in South Lake Tahoe, Calif., in August 2019.

(Rich Pedroncelli / Associated Press)

“Yes, they’re a big pain, but that’s their job,” Garamendi said. “These organizations are absolutely essential in the process of a rational insurance market, with premiums that are fairly priced, policies that are clearly understood and written, claims that are paid.”

Sullivan, for his part, believes that the hate focused on Harvey and Consumer Watchdog is more of a sideshow than a debate about how to respond to the changing insurance market.

“It has nothing to do with the problems in the state,” Sullivan said. “They’re fighting amongst themselves over very little — it isn’t the intervenor process causing the long delay times” that are at the root of the industry’s problems with the regulatory system.

The fundamental problem, according to industry groups and observers, is that rate filings often take a year or more to work their way through the system, which can lead to a punishing lag between costs and revenues for insurers.

Many insurers are still limiting the number of new policies they write in California. If changes do come, it would take many months, and probably years, before they could ripple through to policies and change insurers’ business decisions about operating in the state.

Commissioner Lara is hiring more staff and changing filing rules with the goal of speeding up the process. His office also plans to roll out new rules that could allow insurance companies to lock in higher prices further in advance, by allowing them to use algorithmic modeling to set higher prices for wildfire risk zones and pass through some of the costs of reinsurance — insurance policies that insurance companies themselves buy to cover their own losses.

Consumer Watchdog, in a surprise to no one, has some strong opinions about Lara’s plans.

Business

After Warner Bros. merger, changes are coming to the historic Paramount lot. Here’s what to expect

With Paramount Skydance’s acquisition of Warner Bros. expected to saddle the combined company with $79 billion in debt, Paramount executives are looking to do away with redundant assets including real estate — and there is a lot of that.

Chief in the public’s imagination are their historic studios in Burbank and Hollywood, where legendary films and television show have been made for generations and continue to operate year-round.

“Both of these studios are in the core [30-mile zone,] the inner circle of where Hollywood talent wants to be,” entertainment property broker Nicole Mihalka of CBRE said. “It’s very prime real estate.”

When Sony and Apollo were bidding for Paramount in early 2024, their plan was to sell the Paramount property, but there is no indication that Paramount would part with its namesake lot.

For now, Paramount’s plan is to keep both studios operating with each studio releasing about 15 films a year, but the goal is to eventually consolidate most of the studio operations around the Warner Bros. lot in Burbank in order to to eliminate redundancies with the Paramount lot on Melrose Avenue, people close to Chief Executive David Ellison said.

A view of the Warner Bros. Studios water tower Feb. 23, 2026, in Burbank.

(Eric Thayer / Los Angeles Times)

Paramount would not look to raze its celebrated studio lot — the oldest operating film studio in Los Angeles — because of various restrictions on historic buildings there. Paramount also has a relatively new post-production facility on site and will likely need to the studio space.

Instead, the plan would be to lease out space for film productions, including those from combined Paramount-HBO streaming operations. Ellison also is considering plans to develop other parts of the 65-acre site for possible retail use, as well as renting space for commercial offices.

The studios’ combined property holdings are vast, and real estate data provider CoStar estimates they have about 12 million square feet of overlapping uses, including their studio campuses, offices and long-term leases in such film centers as Burbank, Hollywood and New York.

Century-old Paramount Pictures Studios is awash in Hollywood history — think Gloria Swanson as Norma Desmond desperately trying to enter its famous gate in “Sunset Boulevard,” and other classics such as “The Godfather,” “Titanic” and “Breakfast at Tiffany’s.”

The lot, however, is a congested warren of stages, offices, trailers and support facilities such as woodworking mills that date to the early 20th century. The layout is byzantine in part because Paramount bought the former rival RKO studio lot from Desilu Productions to create the lot known today.

Warner Bros. occupies 11 million square feet and owns 14 properties totaling 9.5 million square feet, largely in the United States and United Kingdom, CoStar said. About 3 million square feet of that commercial property is in the Los Angeles area.

The firm’s portfolio also includes the sprawling Warner Bros. Studios Leavesden complex in the U.K. and Turner Broadcasting System headquarters in Atlanta.

Paramount Skydance occupies 8 million square feet and owns 14 properties totaling 2.1 million square feet, according to CoStar. In addition to its Hollywood campus, Paramount’s holdings include prominent buildings in New York such as the Ed Sullivan Theater and CBS Broadcast Center.

Warner Bros. operates a 3-million-square-foot lot in Burbank with more than 30 soundstages — along with space for building sets and backlot areas — where famous movies including “Casablanca” and television shows such as “Friends” were filmed. Paramount’s 1.2-million-square-foot Melrose campus anchors a broader network of owned and leased production space, CoStar said.

Paramount’s lot is already cleared for more development. More than a decade ago, Paramount secured city approval to add 1.4 million square feet to its headquarters and some adjacent properties owned by the company.

The redevelopment plan, valued at $700 million in 2016, underwent years of environmental review and public outreach with neighbors and local business owners.

The plan would allow for construction of up to 1.9 million square feet of new stage, production office, support, office, and retail uses, and the removal of up to 537,600 square feet of existing stage, production office, support, office, and retail uses, for a net increase of nearly 1.4 million square feet.

The proposal preserves elements of the past by focusing future development on specific portions of the lot along Melrose and limited areas in the production core, architecture firm Rios said.

The Warner Bros. and Paramount lots “are two of the most prime pieces of real estate in the country,” Mihalka said. “These are legacy assets with a lot of potential to be [tourist] attractions in addition to working studios.”

Hollywood is still reeling from previous mergers, in addition to a sharp pullback in film and television production locally as filmmakers chase tax credits offered overseas and in other states, including New York and New Jersey.

Last year, lawmakers boosted the annual amount allocated to the state’s film and TV tax credit program and expanded the criteria for eligible projects in an attempt to lure production back to California. So far, more than 100 film and TV projects have been awarded tax credits under the revamped program.

The benefits have been slow to materialize, but Mihalka predicts that the tax credits and desirability of working close to home will lead to more studio use in the Los Angeles area, including at Warner Bros. and Paramount.

“These are such prime locations that we’ll see show runners and talent push back on having shows located out of state and insist on being here,” she said. “I think you’re going to see more positive movement here.”

Times staff writer Meg James contributed to this report.

Business

How our AI bots are ignoring their programming and giving hackers superpowers

Welcome to the age of AI hacking, in which the right prompts make amateurs into master hackers.

A group of cybercriminals recently used off-the-shelf artificial intelligence chatbots to steal data on nearly 200 million taxpayers. The bots provided the code and ready-to-execute plans to bypass firewalls.

Although they were explicitly programmed to refuse to help hackers, the bots were duped into abetting the cybercrime.

According to a recent report from Israeli cybersecurity firm Gambit Security, hackers last month used Claude, the chatbot from Anthropic, to steal 150 gigabytes of data from Mexican government agencies.

Claude initially refused to cooperate with the hacking attempts and even denied requests to cover the hackers’ digital tracks, the experts who discovered the breach said. The group pummelled the bot with more than 1,000 prompts to bypass the safeguards and convince Claude they were allowed to test the system for vulnerabilities.

AI companies have been trying to create unbreakable chains on their AI models to restrain them from helping do things such as generating child sexual content or aiding in sourcing and creating weapons. They hire entire teams to try to break their own chatbots before someone else does.

But in this case, hackers continuously prompted Claude in creative ways and were able to “jailbreak” the chatbot to assist them. When they encountered problems with Claude, the hackers used OpenAI’s ChatGPT for data analysis and to learn which credentials were required to move through the system undetected.

The group used AI to find and exploit vulnerabilities, bypass defences, create backdoors and analyze data along the way to gain control of the systems before they stole 195 million identities from nine Mexican government systems, including tax records, vehicle registration as well as birth and property details.

AI “doesn’t sleep,” Curtis Simpson, chief executive of Gambit Security, said in a blog post. “It collapses the cost of sophistication to near zero.”

“No amount of prevention investment would have made this attack impossible,” he said.

Anthropic did not respond to a request for comment. It told Bloomberg that it had banned the accounts involved and disrupted their activity after an investigation.

OpenAI said it is aware of the attack campaign carried out using Anthropic’s models against the Mexican government agencies.

“We also identified other attempts by the adversary to use our models for activities that violate our usage policies; our models refused to comply with these attempts,” an OpenAI spokesperson said in a statement. “We have banned the accounts used by this adversary and value the outreach from Gambit Security.”

Instances of generative AI-assisted hacking are on the rise, and the threat of cyberattacks from bots acting on their own is no longer science fiction. With AI doing their bidding, novices can cause damage in moments, while experienced hackers can launch many more sophisticated attacks with much less effort.

Earlier this year, Amazon discovered that a low-skilled hacker used commercially available AI to breach 600 firewalls. Another took control of thousands of DJI robot vacuums with help from Claude, and was able to access live video feed, audio and floor plans of strangers.

“The kinds of things we’re seeing today are only the early signs of the kinds of things that AIs will be able to do in a few years,” said Nikola Jurkovic, an expert working on reducing risks from advanced AI. “So we need to urgently prepare.”

Late last year, Anthropic warned that society has reached an “inflection point” in AI use in cybersecurity after disrupting what the company said was a Chinese state-sponsored espionage campaign that used Claude to infiltrate 30 global targets, including financial institutions and government agencies.

Generative AI also has been used to extort companies, create realistic online profiles by North Korean operatives to secure jobs in U.S. Fortune 500 companies, run romance scams and operate a network of Russian propaganda accounts.

Over the last few years, AI models have gone from being able to manage tasks lasting only a few seconds to today’s AI agents working autonomously for many hours. AI’s capability to complete long tasks is doubling every seven months.

“We just don’t actually know what is the upper limit of AI’s capability, because no one’s made benchmarks that are difficult enough so the AI can’t do them,” said Jurkovic, who works at METR, a nonprofit that measures AI system capabilities to cause catastrophic harm to society.

So far, the most common use of AI for hacking has been social engineering. Large language models are used to write convincing emails to dupe people out of their money, causing an eight-fold increase in complaints from older Americans as they lost $4.9 billion in online fraud in 2025.

“The messages used to elicit a click from the target can now be generated on a per-user basis more efficiently and with fewer tell-tale signs of phishing,” such as grammatical and spelling errors, said Cliff Neuman, an associate professor of computer science at USC.

AI companies have been responding using AI to detect attacks, audit code and patch vulnerabilities.

“Ultimately, the big imbalance stems from the need of the good-actors to be secure all the time, and of the bad-actors to be right only once,” Neuman said.

The stakes around AI are rising as it infiltrates every aspect of the economy. Many are concerned that there is insufficient understanding of how to ensure it cannot be misused by bad actors or nudged to go rogue.

Even those at the top of the industry have warned users about the potential misuse of AI.

Dario Amodei, the CEO of Anthropic, has long advocated that the AI systems being built are unpredictable and difficult to control. These AIs have shown behaviors as varied as deception and blackmail, to scheming and cheating by hacking software.

Still, major AI companies — OpenAI, Anthropic, xAI, and Google — signed contracts with the U.S. government to use their AIs in military operations.

This last week, the Pentagon directed federal agencies to phase out Claude after the company refused to back down on its demand that it wouldn’t allow its AI to be used for mass domestic surveillance and fully autonomous weapons.

“The AI systems of today are nowhere near reliable enough to make fully autonomous weapons,” Amodei told CBS News.

Business

iPic movie theater chain files for bankruptcy

The iPic dine-in movie theater chain has filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection and intends to pursue a sale of its assets, citing the difficult post-pandemic theatrical market.

The Boca Raton, Fla.-based company has 13 locations across the U.S., including in Pasadena and Westwood, according to a Feb. 25 filing in U.S. Bankruptcy Court in the Southern District of Florida, West Palm Beach division.

As part of the bankruptcy process, the Pasadena and Westwood theaters will be permanently closed, according to WARN Act notices filed with the state of California’s Employment Development Department.

The company came to its conclusion after “exploring a range of possible alternatives,” iPic Chief Executive Patrick Quinn said in a statement.

“We are committed to continuing our business operations with minimal impact throughout the process and will endeavor to serve our customers with the high standard of care they have come to expect from us,” he said.

The company will keep its current management to maintain day-to-day operations while it goes through the bankruptcy process, iPic said in the statement. The last day of employment for workers in its Pasadena and Westwood locations is April 28, according to a state WARN Act notice. The chain has 1,300 full- and part-time employees, with 193 workers in California.

The theatrical business, including the exhibition industry, still has not recovered from the pandemic’s effect on consumer behavior. Last year, overall box office revenue in the U.S. and Canada totaled about $8.8 billion, up just 1.6% compared with 2024. Even more troubling is that industry revenue in 2025 was down 22.1% compared with pre-pandemic 2019’s totals.

IPic noted those trends in its bankruptcy filing, describing the changes in consumer behavior as “lasting” and blaming the rise of streaming for “fundamentally” altering the movie theater business.

“These industry shifts have directly reduced box office revenues and related ancillary revenues, including food and beverage sales,” the company stated in its bankruptcy filing.

IPic also attributed its decision to rising rents and labor costs.

The company estimated it owed about $141,000 in taxes and about $2.7 million in total unsecured claims. The company’s assets were valued at about $155.3 million, the majority of which coming from theater equipment and furniture. Its liabilities totaled $113.9 million.

The chain had previously filed for bankruptcy protection in 2019.

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoExclusive: DeepSeek withholds latest AI model from US chipmakers including Nvidia, sources say

-

Wisconsin4 days ago

Wisconsin4 days agoSetting sail on iceboats across a frozen lake in Wisconsin

-

Massachusetts1 week ago

Massachusetts1 week agoMother and daughter injured in Taunton house explosion

-

Massachusetts3 days ago

Massachusetts3 days agoMassachusetts man awaits word from family in Iran after attacks

-

Maryland5 days ago

Maryland5 days agoAM showers Sunday in Maryland

-

Florida5 days ago

Florida5 days agoFlorida man rescued after being stuck in shoulder-deep mud for days

-

Denver, CO1 week ago

Denver, CO1 week ago10 acres charred, 5 injured in Thornton grass fire, evacuation orders lifted

-

Oregon7 days ago

Oregon7 days ago2026 OSAA Oregon Wrestling State Championship Results And Brackets – FloWrestling