Business

Column: ‘Oppenheimer’ is a great movie, but commits these historical blunders

“Oppenheimer” has been justly praised for its attempt at historical fidelity in telling the life story of the brilliant, agonized physicist, but it’s not a documentary.

The movie gets most things right about Oppenheimer’s role in the Manhattan Project, the government effort to build the atomic bomb, as one would expect given that filmmaker Christopher Nolan based it on “American Prometheus,” the superb 2005 biography of J. Robert Oppenheimer by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin.

But artistic imperatives and Nolan’s understandable choice to tell his story from Oppenheimer’s point of view led him to perpetuate a few myths about the making of the atomic bomb and to gloss over aspects of the story that may be interesting for lay viewers.

Oppie, is it a secret?

— Physicist Paul Ehrenfest, trying to decipher Oppenheimer’s unintelligible mumbling at a Caltech lecture

Based on what I gleaned about Oppenheimer and the project from researching my 2015 biography of Berkeley physicist Ernest O. Lawrence (played in the movie by Josh Hartnett), “Big Science,” I’ll try to correct the Hollywood record and fill in the gaps.

Let’s jump in.

For the most part, Nolan sticks to the facts. “Oppenheimer” is notable among biopics for portraying real people doing the things they did at the time. Even peripheral characters who flit briefly across the screen are given their real names or identifiable characteristics.

As far as I can tell, the only imaginary or composite character in the film is the unnamed Senate aide played by Alden Ehrenreich, whose dramatic function is to be a sounding board for the grousing of Lewis L. Strauss (brilliantly played by Robert Downey Jr.), Oppenheimer’s political nemesis.

That bongo-playing physicist glimpsed at the Trinity plutonium bomb test in the New Mexico desert? Unnamed in the film, he’s Richard Feynman, later to be revered as Caltech’s resident genius but, at 24, attached to the Los Alamos bomb lab at the very beginning of his scientific career. (He did bring his bongos to the desert.)

Lawrence’s associate Luis Alvarez, later a Nobel laureate, is accurately portrayed as bursting into an Oppenheimer seminar in 1939 with the first news of the discovery of nuclear fission by German physicists Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassmann. The film also accurately shows Oppenheimer instantly responding, “That’s impossible,” promptly withdrawing his snap judgment and, within a week, outlining how the discovery might be used to make a bomb.

But the film doesn’t cover Alvarez’s resentful and damaging testimony in the Oppenheimer security hearing, during which he claimed to have heard Vannevar Bush, the top science advisor to Presidents Franklin Roosevelt and Harry Truman, reveal that Truman had not trusted Oppenheimer. Bush — who is played by Matthew Modine — vociferously contradicted the story.

The most glaring historical gaffe is the film’s perpetuation of the myth that Oppenheimer was the boss of the Manhattan Project; it shows him assuring Gen. Leslie R. Groves that he can run the project. (Matt Damon would have had to put on at least 50 or 60 pounds to more accurately impersonate Groves, who tipped the scales at nearly 300 pounds.)

Oppenheimer was merely the boss of Los Alamos, one of the project’s numerous separate labs and technical installations. Its job was to actually build the bomb, drawing on the research of labs at Columbia, the University of Chicago and Berkeley. Though Groves was the overall boss, the project’s scientific management was divided, rather tetchily, between Lawrence and Arthur Holly Compton of the University of Chicago.

Lawrence was the scientist whose advice Groves trusted the most. He originally wanted Lawrence to run the lab that was eventually built at Los Alamos, but decided Lawrence was too important to be limited to the bomb-designing task.

Oppenheimer was Groves’ second choice, but he turned to Lawrence for assurance that Oppenheimer could effectively run the bomb lab.

Lawrence, who at that time was a close friend of Oppenheimer, his valued colleague at UC Berkeley — he named his first son Robert after Oppenheimer — assuaged Groves’ concerns about Oppenheimer’s leftist politics and lack of a Nobel Prize. Lawrence sealed the deal for his friend by promising Groves that if Oppenheimer failed in his task, he would take it over himself.

A few words about Ernest Lawrence. Before and during the war, the South Dakota native was the most famous and influential scientist in America — arguably the first home-grown scientific celebrity in American history.

The scientists of Ernest Lawrence’s Radiation Lab at UC Berkeley in 1938, framed by the magnet for the 60-inch cyclotron. Lawrence is seated in the front row, fifth from the left; J. Robert Oppenheimer is standing in the back row, fifth from the left.

(Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory)

The inventor of the cyclotron, the most important atom-smasher of its era and the invention that transformed particle physics in the 1930s, Lawrence was featured on the cover of Time magazine on Nov. 1, 1937, over the caption “He creates and destroys,” and won the Nobel Prize in 1939.

Lawrence’s skill at explaining complex scientific principles in lay terms kept him in the public eye via radio talks and newspaper articles and helped him attract millions of dollars in foundation and government funding for his Radiation Laboratory — the “Rad Lab” — at UC Berkeley. It was due to his influence that UC was awarded the contract to run Los Alamos after the war, which it still holds, albeit with somewhat diminished authority. Lawrence also invented a color TV system that was eventually incorporated into Sony’s Trinitron technology.

Oppenheimer, by contrast, was almost entirely unknown to the general public until after the bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945, when he was thrust into fame as “the father of the atomic bomb.”

Among the physics fraternity, however, Oppenheimer was virtually a cult figure, which is painted only murkily in the film. His graduate students at Berkeley and Caltech, where he held joint appointments, chain-smoked his brand of cigarettes (Chesterfields), imitated his loping gait, and replicated the almost unintelligible mumbling of his lecturing style.

Austrian physicist Paul Ehrenfest, a friend of Oppenheimer’s who sat through one of his Caltech lectures straining to make out his words, finally blurted out, “Oppie, is it a secret?”

Another myth perpetuated by the film is that the physicists were afraid that the bomb blast might ignite the atmosphere, destroying the world. “Oppenheimer” depicts this possibility being debated almost as late as the Trinity test. In fact, it had been raised very briefly in 1942 and promptly put to rest by Manhattan Project physicist Hans Bethe, who later called it “absolute nonsense.”

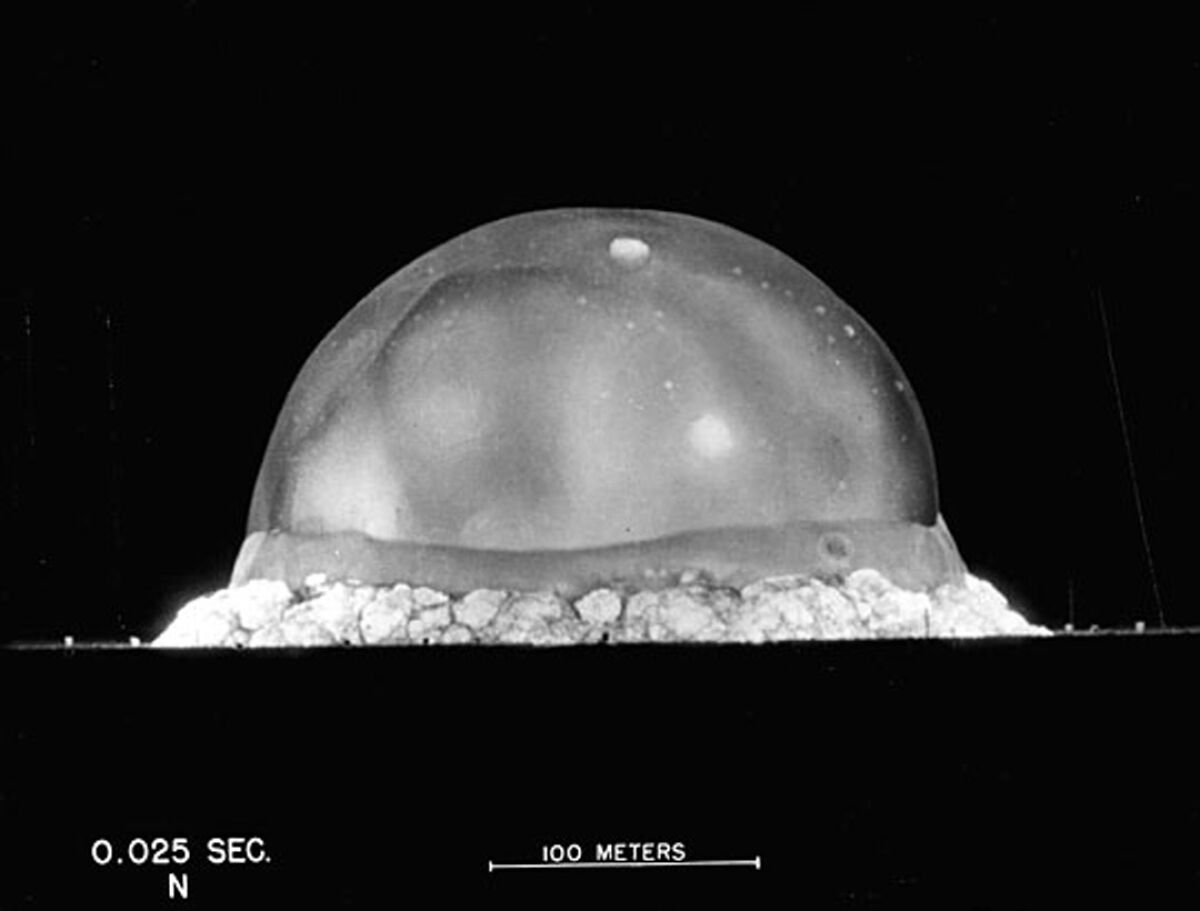

One more point concerns Oppenheimer’s recollection that upon witnessing the fireball produced by the Trinity test, he immediately thought of a line from the Sanskrit Bhagavad-Gita: “I am become death, destroyer of worlds.”

The film takes him at his word, but the truth is that he never mentioned this in public until 1965; one friend considered the claim to be one of Oppenheimer’s “priestly exaggerations.” By the way, the line from the Hindu scripture has been translated in other ways, notably as “I am become time, destroyer of worlds,” perhaps a subtler and more sinister thought than Oppie’s version.

Some aspects of the 1954 security hearing as depicted in the film warrant further examination. The film accurately shows that Groves, asked if he would give Oppenheimer a security clearance at the time of the hearing, answered carefully that he would not, under the stringent security rules imposed by the Atomic Energy Commission. But his subsequent sotto voce remark, to the effect that he probably wouldn’t give any of the Manhattan Project scientists clearance under those rules, doesn’t appear anywhere in the 1,011-page hearing transcript.

Then there’s Lawrence’s decision not to testify against his old friend. By 1954, Lawrence and Oppenheimer had had a bitter falling-out. The film attributes this mostly to Lawrence’s fury upon learning that Oppenheimer had carried on an affair with the wife of Caltech physicist Richard Tolman, a close friend of Lawrence. Tolman committed suicide shortly after learning of the betrayal, which Lawrence ascribed to his broken heart.

But another reason for their split was Oppie’s campaigning against the hydrogen bomb program, which Lawrence favored and which was a major source of government patronage for his lab — Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, an offshoot of the Rad Lab, had been founded largely to pursue research on the so-called Super.

The Trinity test fireball, 25 thousands of a second after its detonation at the Alamogordo bombing range in New Mexico at 5:29 a.m. Mountain time on July 16, 1945, ushering in a new reality for humankind.

(Los Alamos National Laboratory)

Although Lawrence had promised Strauss, who as chairman of the AEC oversaw all civilian government nuclear research and stage-managed the security hearing, that he would testify, he was racked with second thoughts as his appearance date approached.

Lawrence knew that the physics community overwhelmingly supported Oppenheimer, and that Berkeley had become the center of anti-Oppenheimer sentiment, in part because of the conflict over the H-bomb program. This was not a good look for the Rad Lab.

Contrary to the film’s depiction, Lawrence never actually showed up outside the hearing room. Instead, he phoned Strauss the Monday before his scheduled appearance from the government’s Oak Ridge lab, which he had founded and designed for the production of enriched uranium for the bomb ultimately dropped on Hiroshima (the Trinity test was of a plutonium bomb like that dropped on Nagasaki, which was a much more complicated engineering challenge).

As the film shows, Lawrence pleaded a medical excuse — an outbreak of ulcerative colitis, the condition that would ultimately kill him in 1958. After Strauss responded with a vicious tongue-lashing over the phone, culminating in an accusation of cowardice, Lawrence summoned his fellow Oak Ridge guests, all government lab directors, to prove he was not feigning illness by showing them his toilet, brimming with bright red blood.

Christopher Nolan’s film implicitly asks viewers to come to their own conclusions about the moral dimension of the decision to drop the bomb on Japan. A committee of four physicists — Oppenheimer, Lawrence, Compton and Fermi — was tasked with the options, which included staging a demonstration at an uninhabited Pacific island to show Japanese officials what they faced if they didn’t surrender.

Lawrence, who had worked with Japanese scientists to build the first cyclotrons outside the U.S., was the last member of the committee to agree that using the bomb was the only choice, for the possibility of a dud demonstration was too great to risk. As the committee chair, Oppenheimer signed the one-page memo, dated June 16, 1945, that came to the dismaying conclusion that “we see no acceptable alternative to direct military use.”

What the physicists didn’t know was that the decision already had been taken out of their hands. That Boeing B-29 bombers that would carry the bombs had already been assembled on Tinian Island, 1,500 miles south of Japan, and the military decision to use the bombs was preordained.

How should we think about the development of nuclear weapons and Oppenheimer’s role? My view is that the Manhattan Project was understandable and defensible given the wartime context. Allied physicists, especially refugees from the Nazi regime, knew that although Hitler had driven away Jewish scientists, the physicists left behind in Germany were among the best in the world, perfectly capable of developing the atomic bomb. They were in a panic that Hitler might get the weapon before the Allies.

They had no way of knowing that, as the Allies discovered after Germany’s surrender, there had been no German bomb project because the Germans miscalculated the physics involved and didn’t have access to the resources and equipment, including the cyclotron, in the U.S. and Britain.

The decision to pursue the hydrogen bomb is another story. Fermi and other leading physicists understood that its incredible power meant it could only be a weapon of genocide. Some worked on it anyway. Oppenheimer’s notion that nuclear research should be placed under international control to forestall the perils of nuclear proliferation was idealistic, but in terms of geopolitical reality hopelessly naive. There was no way that the U.S. and Britain would cede control of the technology to any international body after 1945.

The tragic message of Oppenheimer and “Oppenheimer” is that humankind has lived under a nuclear sword of Damocles ever since.

Business

Darren Aronofsky joins AI Hollywood push with Google deal

Director Darren Aronofsky has pushed artistic boundaries with movies including “Requiem for a Dream” and “Mother!”

Now his production company is working with Google to explore the edge of artificial intelligence technology in filmmaking.

Google on Tuesday said it is working with several filmmakers to use new AI tools as part of a larger push to popularize the fast-moving tech. That effort includes a partnership with Aronofsky’s venture, Primordial Soup.

Google’s AI-focused subsidiary DeepMind and Aronofsky’s firm will work with three filmmakers, giving them access to the Mountain View, Calif.-based giant’s text-to-video tool Veo, which they will use to make short films. The first project, “Ancestra,” is directed by Eliza McNitt. Aronofsky is an executive producer on the film. “Ancestra,” which premieres at the Tribeca Festival next month, combines live-action filmmaking with imagery generated with AI, such as cosmic events and microscopic worlds.

“Filmmaking has always been driven by technology,” Aronofsky said in a statement that referenced film tech pioneers the Lumiere brothers and Thomas Edison. “Today is no different. Now is the moment to explore these new tools and shape them for the future of storytelling.”

The push comes as Google and other companies are making deals with Hollywood talent and production companies to use their AI tools. For example, Facebook parent company Meta is partnering with “Titanic” director James Cameron’s venture, Lightstorm Vision, to co-produce content for its virtual reality headset Meta Quest. New York-based AI startup Runway has a deal with “Hunger Games” studio Lionsgate to create a new AI model to help with behind-the-scenes processes such as storyboarding.

Many people in Hollywood have been critical of AI tools, raising concerns about the automation of jobs. Writers worry about AI models being trained on their scripts without their permission or compensation. Tech industry executives have said that they should be able to train AI models with content available online under the “fair use” doctrine, which allows for the limited reproduction of material without permission from the copyright holder.

Proponents of the technology say that it can provide more opportunities for filmmakers to test out ideas and show a variety of visuals at a lower cost.

New York-based Primordial Soup said in a press release that Google’s AI tools helped solve “practical challenges such as filming with infants and visualizing the birth of the universe” in “Ancestra.”

“With ‘Ancestra,’ I was able to visualize the unseen, transforming family archives, emotions, and science into a cinematic experience that feels both intimate and expansive,” McNitt said in a statement.

The two additional filmmakers and films participating in the Google DeepMind-Primordial Soup deal are not yet named.

Google made the announcement as part of its annual I/O developer conference in Mountain View.

During the event’s keynote address on Tuesday, Google shared updates on its AI tools for filmmakers, including Veo 3, which allows creators to type in how they want dialogue to sound and add sound effects. The company also unveiled a new AI filmmaking tool called Flow that helps users create cinematic shots and stitch together scenes into longer films and short stories.

“This opens up a whole new world of possibilities,” said Demis Hassabis, chief executive of Google DeepMind, in a news briefing on Monday. “We’re excited for how our models are helping power new tools for creativity.”

Flow is available through Google’s new $249.99 monthly subscription plan Google AI Ultra, which includes early access to Veo 3, as well as other benefits including YouTube Premium, Google’s AI models Gemini and other tools. Flow is also available with a $19.99-a-month Google AI Pro subscription.

Google is making other investments related to AI. On Tuesday, L.A.-based generative AI studio Promise announced Google AI Futures Fund as one of its new strategic investors. Through the partnership, Promise will integrate some of Google’s AI technologies into its production pipeline and workflow software and collaborate with Google’s AI teams.

Business

Commentary: Who's responsible for the aviation mess? Transportation Secretary Duffy says it's everyone but him

Picking out the worst performer among Donald Trump’s Cabinet appointees is a tough job — it’s a competitive race, after al l— but one member who deserves to be in the running by almost any measure of incompetence is Sean Duffy, the secretary of Transportation.

Duffy is a classic example of someone who knows who’s responsible for the screwups on his watch, and it’s never him.

He has spent the last weeks and months blaming the Biden administration for numerous operational failures in our air traffic system since he took over. Those include the Jan. 29 midair collision over Washington, D.C., that cost 67 air passengers their lives, as well as several near-misses on the ground.

I think we need to be a little bit more precise in downsizing a department with a mission as critical as DOT’s.

— Rep Steve Womack (R-Ark.)

Some Trump Cabinet members have more important portfolios than Duffy —Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem and Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth, neither of whom has displayed anything approaching basic competence at their job, come immediately to mind.

But the American public is bound to be particularly sensitive to the functioning of our transportation infrastructure. That’s especially true when it comes to the safety and reliability of air travel; every flight delay and safety-related mishap hits American travelers in the gut.

The highest-profile failure (so far) is the disaster named Newark Liberty International Airport, where flight delays can last for the better part of a day and questions about safety are rife.

Duffy, a former reality show contestant and four-term congressman, comes to the blame game with dirty hands. Let’s take a look.

First, here’s what he’s said about the condition of FAA operations and staffing.

“I think it is clear that the blame belongs with the last administration,” he said Monday during a news conference at DOT headquarters. “Pete Buttigieg and Joe Biden did nothing to fix the system that they knew was broken.” He said, “During COVID, when people weren’t flying? That was a perfect time to fix these problems.”

A couple of points are pertinent here. First, in 2019, when Duffy was a Republican member of Congress from Wisconsin, the bill to fund the Department of Transportation among other agencies came before the House. Duffy voted against it. So did 179 other members of the GOP caucus; 12 Republicans joined the Democrats to pass the measure.

Second, the pandemic year in which “people weren’t flying” was 2020. That year, the domestic passenger count plummeted to 369.4 million from 926.7 million the previous year. It was the lowest figure since 1984.

Who was president in 2020? Not Biden, but Donald Trump.

After 2020, passenger loads crept back up, reaching 666.2 million in 2021 and continuing higher to the record of 982.7 million last year. If there was an opportunity to upgrade the air traffic system at the least inconvenience to passengers, it was 2020. But nothing was done then, on Trump’s watch.

I asked the Department of Transportation last week if Duffy could reconcile these evidently misleading and inconsistent statements. I’m still waiting for a reply.

Duffy has maintained that it’s still safe to fly in and out of Newark, despite outages during which air traffic controllers’ screens went black and radios went silent — for 30 seconds on April 28 and 90 seconds on May 9. A backup system failed at the airport May 11 for 45 minutes, causing delays and cancellations for hundreds of flights.

Duffy admitted to the right-wing radio host David Webb on May 12 that he had switched his wife’s flight reservation for the next day from Newark to LaGuardia airport. He subsequently explained that he didn’t say to do so because he thought Newark was unsafe, but to spare her a long delay. In other words, he had found a solution for his family, but not for the overall traveling public, which didn’t speak well for his management of the mess at Newark.

It’s proper to note that the Federal Aviation Administration has been in an operational funk for years. Duffy can try to blame Biden, but that’s a smokescreen. During Trump’s first term, when the FAA’s problems were well known, hiring and deployment of air traffic controllers actually shrank from the level during the Obama administration according to the DOT’s inspector general, to the point where staffing “could not keep pace with attrition.”

In the first budget he submitted after taking office in 2017, Trump proposed slashing the DOT budget by 13%. The budget plan called for cutting 30,000 workers from the FAA staff.

The problems date back even further — at least to 1981, when Ronald Reagan fired 11,000 air traffic controllers at a single blow to break their union. A frenzy of hiring and training followed, but the replacement cohort has passed its retirement age. The FAA is currently about 3,000 controllers shy of its target staffing, so the people on the job are stretched to their breaking point.

It isn’t as if Trump and Duffy pulled out all the stops to fix the FAA’s chronic problems upon taking office. Some 3,000 “probationary” employees at the agency were fired during a DOGE rampage, according to a count by the Professional Aviation Safety Specialists, the union representing safety and technical workers at the FAA, and a statement by Rep. Steve Womack (R-Ark.), chair of the subcommittee overseeing the Transportation Department budget. The probationary firings and two subsequent rounds of buyouts will bring staffing at the DOT down by 12% since Trump took office.

During appearances last week before the House and Senate appropriations committees, Duffy boasted about saving taxpayers nearly $10 billion during the first 100 days of the Trump administration. That provoked Womack to riposte, “I think we need to be a little bit more precise in downsizing a department with a mission as critical as DOT’s. … The question is pretty simple: How many departures can you handle without eroding the ability to carry out a safe and effective mission?”

“We can do more with less, Mr. Chairman,” Duffy replied. When staff accept buyout offers to retire or resign, he said, “we should take them up on that. … If I have people who don’t want to be there, let’s get some people in who are hungry to do the work.” Indeed, after the first round of firings at the FAA, DOGE boss Elon Musk issued a public appeal that air traffic controllers who had “retired, but are open to returning to work, please consider doing so.”

Furthermore, Trump’s freeze on disbursement of funds from Biden’s Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act and Inflation Reduction Act encompassed modernization projects at airports nationwide.

Musk’s fingerprints were also on the resignation of FAA Administrator Michael Whitaker, a former airline executive and former FAA deputy administrator who had been unanimously confirmed to a five-year term in October 2023. Whitaker resigned as of Jan. 20 after clashing with Musk over the FAA’s oversight of SpaceX, which Musk owns.

Trump has nominated Republic Airways Chief Executive Bryan Bedford as his replacement, but Bedford hasn’t been confirmed.

During his Senate appropriations committee testimony on Thursday, Duffy maintained that his budget cuts and firings hadn’t compromised safety at all. He specifically denied that any air traffic controllers had been fired or offered buyouts.

Unfortunately for Duffy, Sen. Patty Murray (D-Wash.), a lawmaker whose mild demeanor masks her habit of coming to a debate with hard information in hand, was in the room. She listed for Duffy all the steps he had taken that had caused “unacceptable chaos” in the air transport system.

Since Jan. 20, she said, “virtually every dollar and transportation project has been held up at some point. You are causing a traffic jam, from freezing funding for projects to creating new hurdles by reevaluating grants that had already been approved, adding red tape by forcing unacceptable political demands on state and local transportation agencies, and outright canceling and cutting grants. … No prior Transportation secretary has cut funding for previously awarded grants in this manner.”

As for Duffy’s blaming the Biden administration “for absolutely everything,” Murray continued, “the last administration did not make the decision to hold up thousands of grants, had nothing to do with the new red tape that you have created, and certainly did not let go of hundreds of staff to help get those grants out the door.”

Turning to Duffy’s assertion that no air traffic controllers had been fired or bought out, Murray told him, “While you talk about modernizing the air traffic control system, you have forced out more than 2,000 FAA employees who support those air traffic controllers — the technicians, the mechanics, the engineers, the IT specialists at the FAA who were working on modernization.”

Duffy, indeed, stepped on his own arguments. He complained that the Biden administration had saddled him with some 3,200 contracts that had been awarded but needed to be signed. But he acknowledged that he had to go through those contracts to eliminate provisions he thought smacked of “wasteful DEI and climate requirements.” These are ideological shibboleths and by no means “wasteful,” since DOT projects have manifest effects on the welfare of residents in the communities where they’re built or planned and on climate change itself.

As it happens, on April 24, Duffy sent a letter to all recipients of DOT funds —effectively virtually every state and thousands of local jurisdictions, warning them that pursuing “DEI goals … violates federal law.” He threatened explicitly to withhold DOT funding from jurisdictions that fail to cooperate with federal immigration authorities. This is the “red tape” that Murray referenced.

Whether DEI programs and failures to cooperate with federal immigration roundups really violate federal law, as Duffy asserted, is not remotely a settled legal question, but the matter is before federal judges across the land. The fact that Duffy is wasting his time by making these threats and combing through awarded contracts to ferret out such putative violations is, however, a settled question: Of course he is.

It may not be long now before Duffy’s ideological vetting of transportation contracts and his decimation of the working staff at the FAA cause even greater disruptions in the air and on land, potentially with fatal consequences. His efforts to blame everyone else for his own failures are sure to have a very short half-life. Raise your tray tables and your reclining seats, and fasten your seat belts. We may be coming in for a hard landing.

Business

23andMe sells gene-testing business to DNA drug maker Regeneron

Bankrupt genetic-testing firm 23andMe agreed to sell its data bank, which once contained DNA samples from about 15 million people, to the drug developer Regeneron Pharmaceuticals for $256 million.

The sale comes after a wave of customers and government officials demanded that 23andMe protect the genetic data it had built up over the years by collecting saliva samples from customers.

Regeneron pledged to comply with 23andMe’s privacy policy, which allows customers to have their personal information deleted upon request.

“We have deep experience with large-scale data management,” Regeneron co-founder George D. Yancopoulos said in a statement. The company “has a proven track record of safeguarding the genetic data of people across the globe, and, with their consent, using this data to pursue discoveries that benefit science and society.”

23andMe filed for bankruptcy in March after failing to generate sustainable profits by providing medical and ancestry-related genetic testing to more than 15 million customers.

About 550,000 people had subscribed to the company’s two primary services, which hasn’t been enough to keep the company afloat. One of those services, Lemonaid Health, was not part of the sale and will be wound down, 23andMe said in a statement.

As part of 23andMe’s Chapter 11 bankruptcy, a judge approved the appointment of a privacy ombudsman to monitor the sale process and ensure compliance with privacy policies related to the genetic material submitted by customers.

That material, and the genetic data it produced, was 23andMe’s most valuable asset. The company has said any buyer must comply with current privacy protections and federal regulations.

Regeneron said it will continue to run 23andMe’s personal genomic services once the sale closes. The judge overseeing the bankruptcy must approve the sale before it can be completed.

In the months leading up its bankruptcy, 23andMe tried to attract a buyer while struggling to end a class-action lawsuit related to a 2023 data breach that gave hackers access to customer information. The company will try to resolve those claims as part of the bankruptcy.

The case is 23andMe Holding Co., number 25-40976, in the U.S. Bankruptcy Court for the Eastern District of Missouri.

Church and Smith write for Bloomberg.

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoMexico is suing Google over how it’s labeling the Gulf of Mexico

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoDHS says Massachusetts city council member 'incited chaos' as ICE arrested 'violent criminal alien'

-

Education1 week ago

Education1 week agoA Professor’s Final Gift to Her Students: Her Life Savings

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoPresident Trump takes on 'Big Pharma' by signing executive order to lower drug prices

-

Education1 week ago

Education1 week agoVideo: Tufts Student Speaks Publicly After Release From Immigration Detention

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoAs Harvard Battles Trump, Its President Will Take a 25% Pay Cut

-

Culture1 week ago

Culture1 week agoTest Yourself on Memorable Lines From Popular Novels

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoWhy Trump Suddenly Declared Victory Over the Houthi Militia