Business

Boeing is looking to jettison the space business. Why it might hold on to its El Segundo satellite operation

With its manufacturing practices under scrutiny, its machinists on strike and losses piling up, Boeing is said to be considering selling parts of its fabled space business. But few industry analysts think Boeing will put its extensive El Segundo satellite operations on the table.

New Boeing Chief Executive Kelly Ortberg said during a recent earnings call that the aerospace giant was considering shedding assets outside of the company’s core commercial aviation and defense businesses, adding that Boeing was better off “doing less and doing it better than doing more and not doing it well.”

That could mean that Boeing sees no future for its troubled Starliner spacecraft, which was developed to service the International Space Station. The Arlington, Va., aerospace giant also has been trying to exit its United Launch Alliance joint launch venture with Lockheed Martin. Both programs face stiff competition from Elon Musk’s SpaceX, which recently announced it was moving its headquarters from Hawthorne to Brownsville, Texas.

But any asset sale is not expected to encompass Boeing’s satellite manufacturing operations in El Segundo, which include a 1-million-square-foot plant with several thousand workers it acquired in 2000 with its purchase of Hughes Electronics Corp.’s space and communications business.

“It’s not a booming growth business, but there’s no reason for Boeing to get out anytime soon,” said Marco Caceres, an aerospace analyst at Teal Group, noting the continuing demand for the large satellites made at the facility despite changes in the industry.

Shedding parts of it space business would be a landmark decision for Boeing, which has deep ties to the space program in Southern California — where it has built rockets, the X-37 space plane and components for the space station.

Ortberg’s comments come amid manufacturing concerns over its key 737 commercial jet program and a machinists strike that is estimated to be costing $50 million a day. Boeing raised $21 billion in a stock sale this week to shore up its balance sheet.

Boeing also has been the target of multiple whistleblower lawsuits that have alleged lax safety and manufacturing practices that resulted in quality-control issues.

The Wall Street Journal first reported that Boeing was considering selling parts of its space business last week. A Boeing spokesperson said the company “doesn’t comment on market rumors or speculation.”

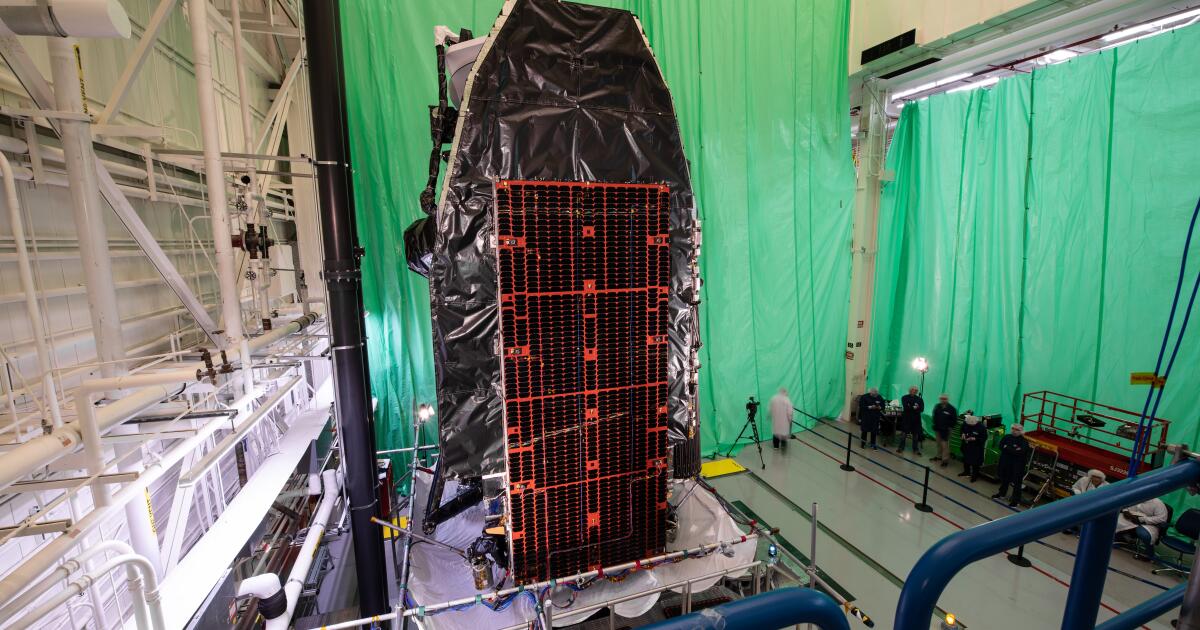

The El Segundo satellite plant makes large satellites for commercial, government and military customers, including the O3b mPOWER communications satellite for SES, a Luxembourg telecommunications company. Other programs include a $440-million defense contract that Boeing was awarded in March to build another Wideband Global Satcom satellite, which provide fast and secure communications for the U.S. and its allies.

Caceres said manufacturing large satellites remains lucrative for now, though the trend has been for networks of thousands of smaller satellites, such as SpaceX’s Starlink broadband network.

“It’s still a good business but it’s going to be diminished, because it really is these big, mega-constellation systems that are the future,” he said.

In 2018, Boeing acquired a maker of small satellites called Millennium Space Systems, which also is based in El Segundo and whose operations have been partially integrated with the company’s existing plant. The company has received U.S. defense contracts for satellites to detect new threats such as hypersonic missiles.

Other Boeing space businesses in the region expected to survive any restructuring include Spectrolab, a Sylmar subsidiary that makes solar cells for satellites and other space applications. Boeing also is expected to continue its participation in the Space Launch System, a massive rocket developed in Huntsville, Ala., that NASA plans to use to send astronauts back to the moon.

The clearest choice for a possible sale or program closure, analysts agree, is the Starliner capsule built to service the International Space Station with crews and supplies. The spacecraft was manufactured at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida and launches from nearby Cape Canaveral Space Force Station.

Boeing was awarded a $4.6-billion contract in 2014 to develop the craft and has been hit with some $1.5 billion in cost overruns, but the vehicle has yet to be certified. Meanwhile, SpaceX was awarded a smaller contract to develop a crewed capsule, based on its existing Cargo Dragon capsule, and that craft has made more than a dozen trips to the station.

In a blow to Boeing, NASA decided in August to have SpaceX return two astronauts brought to the space station by Starliner in June after the capsule developed propulsion problems while docking on its third test flight. Although the Starliner returned remotely in September, NASA and Boeing are still investigating what went wrong.

Also seen as expendable is Boeing’s participation in the United Launch Alliance, a joint venture it formed in 2006. It claims a perfect mission success rate in more than 150 military and commercial launches. ULA is based in Denver and launches from Cape Canaveral and Vandenberg Space Force Base in Santa Barbara County.

The venture introduced its new Vulcan Centaur rocket this year, which is partly reusable and lowers launch costs to about $110 million. It is more powerful than its SpaceX competitor, the Falcon 9, but that rocket has a fully reusable booster and flight costs starting at less than $70 million.

The space industry has been rife with speculation about who might acquire ULA — Jeff Bezos’ Blue Origin space company has been rumored as a possible buyer — but no deal has emerged, possibly because the price is too high, said Laura Forczyk, executive director of space industry consulting firm Astralytical.

Although the business is not as strong as it used to be, ULA’s reliability, a shortage of launch vehicles and the new rocket’s technical advances means it can still attract business, she said, adding: “There’s just so much demand for launch services.”

Business

Commentary: A leading roboticist punctures the hype about self-driving cars, AI chatbots and humanoid robots

It may come to your attention that we are inundated with technological hype. Self-driving cars, human-like robots and AI chatbots all have been the subject of sometimes outlandishly exaggerated predictions and promises.

So we should be thankful for Rodney Brooks, an Australian-born technologist who has made it one of his missions in life to deflate the hyperbole about these and other supposedly world-changing technologies offered by promoters, marketers and true believers.

As I’ve written before, Brooks is nothing like a Luddite. Quite the contrary: He was a co-founder of IRobot, the maker of the Roomba robotic vacuum cleaner, though he stepped down as the company’s chief technology officer in 2008 and left its board in 2011. He’s a co-founder and chief technology officer of RobustAI, which makes robots for factories and warehouses, and former director of computer science and artificial intelligence labs at Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Having ideas is easy. Turning them into reality is hard. Turning them into being deployed at scale is even harder.

— Rodney Brooks

In 2018, Brooks published a post of dated predictions about the course of major technologies and promised to revisit them annually for 32 years, when he would be 95. He focused on technologies that were then — and still are — the cynosures of public discussion, including self-driving cars, human space travel, AI bots and humanoid robots.

“Having ideas is easy,” he wrote in that introductory post. “Turning them into reality is hard. Turning them into being deployed at scale is even harder.”

Brooks slotted his predictions into three pigeonholes: NIML, for “not in my lifetime,” NET, for “no earlier than” some specified date, and “by some [specified] date.”

On Jan. 1 he published his eighth annual predictions scorecard. He found that over the years “my predictions held up pretty well, though overall I was a little too optimistic.”

For example in 2018 he predicted “a robot that can provide physical assistance to the elderly over multiple tasks [e.g., getting into and out of bed, washing, using the toilet, etc.]” wouldn’t appear earlier than 2028; as of New Year’s Day, he writes, “no general purpose solution is in sight.”

The first “permanent” human colony on Mars would come no earlier than 2036, he wrote then, which he now calls “way too optimistic.” He now envisions a human landing on Mars no earlier than 2040, and the settlement no earlier than 2050.

A robot that seems “as intelligent, as attentive, and as faithful, as a dog” — no earlier than 2048, he conjectured in 2018. “This is so much harder than most people imagine it to be,” he writes now. “Many think we are already there; I say we are not at all there.” His verdict on a robot that has “any real idea about its own existence, or the existence of humans in the way that a 6-year-old understands humans” — “Not in my lifetime.”

Brooks points out that one way high-tech promoters finesse their exaggerated promises is through subtle redefinition. That has been the case with “self-driving cars,” he writes. Originally the term referred to “any sort of car that could operate without a driver on board, and without a remote driver offering control inputs … where no person needed to drive, but simply communicated to the car where it should take them.”

Waymo, the largest purveyor of self-driven transport, says on its website that its robotaxis are “the embodiment of fully autonomous technology that is always in control from pickup to destination.” Passengers “can sit in the back seat, relax, and enjoy the ride with the Waymo Driver getting them to their destination safely.”

Brooks challenges this claim. One hole in the fabric of full autonomy, he observes, became clear Dec. 20, when a power blackout blanketing San Francisco stranded much of Waymo’s robotaxi fleet on the streets. Waymos, which can read traffic lights, clogged intersections because traffic lights went dark.

The company later acknowledged its vehicles occasionally “require a confirmation check” from humans when they encounter blacked-out traffic signals or other confounding situations. The Dec. 20 blackout, Waymo said, “created a concentrated spike in these requests,” resulting in “a backlog that, in some cases, led to response delays contributing to congestion on already-overwhelmed streets.”

It’s also known that Waymo pays humans to physically deal with vehicles immobilized by — for example — a passenger’s failure to fully close a car door when exiting. They can be summoned via the third-party app Honk, which chiefly is used by tow truck operators to find stranded customers.

“Current generation Waymos need a lot of human help to operate as they do, from people in the remote operations center to intervene and provide human advice for when something goes wrong, to Honk gig workers scampering around the city,” Brooks observes.

Waymo told me its claim of “fully autonomous” operation is based on the fact that the onboard technology is always in control of its vehicles. In confusing situations the car will call on Waymo’s “fleet response” team of humans, asking them to choose which of several optional paths is the best one. “Control of the vehicle is always with the Waymo Driver” — that is, the onboard technology, spokesman Mark Lewis told me. “A human cannot tele-operate a Waymo vehicle.”

As a pioneering robot designer, Brooks is particularly skeptical about the tech industry’s fascination with humanoid robots. He writes from experience: In 1998 he was building humanoid robots with his graduate students at MIT. Back then he asserted that people would be naturally comfortable with “robots with humanoid form that act like humans; the interface is hardwired in our brains,” and that “humans and robots can cooperate on tasks in close quarters in ways heretofore imaginable only in science fiction.”

Since then it has become clear that general-purpose robots that look and act like humans are chimerical. In fact in many contexts they’re dangerous. Among the unsolved problems in robot design is that no one has created a robot with “human-like dexterity,” he writes. Robotics companies promoting their designs haven’t shown that their proposed products have “multi-fingered dexterity where humans can and do grasp things that are unseen, and grasp and simultaneously manipulate multiple small objects with one hand.”

Two-legged robots have a tendency to fall over and “need human intervention to get back up,” like tortoises fallen on their backs. Because they’re heavy and unstable, they are “currently unsafe for humans to be close to when they are walking.”

(Brooks doesn’t mention this, but even in the 1960s the creators of “The Jetsons” understood that domestic robots wouldn’t rely on legs — their robot maid, Rosie, tooled around their household on wheels, a perception that came as second nature to animators 60 years ago but seems to have been forgotten by today’s engineers.)

As Brooks observes, “even children aged 3 or 4 can navigate around cluttered houses without damaging them. … By age 4 they can open doors with door handles and mechanisms they have never seen before, and safely close those doors behind them. They can do this when they enter a particular house for the first time. They can wander around and up and down and find their way.

“But wait, you say, ‘I’ve seen them dance and somersault, and even bounce off walls.’ Yes, you have seen humanoid robot theater. “

Brooks’ experience with artificial intelligence gives him important insights into the shortcomings of today’s crop of large language models — that’s the technology underlying contemporary chatbots — what they can and can’t do, and why.

“The underlying mechanism for Large Language Models does not answer questions directly,” he writes. “Instead, it gives something that sounds like an answer to the question. That is very different from saying something that is accurate. What they have learned is not facts about the world but instead a probability distribution of what word is most likely to come next given the question and the words so far produced in response. Thus the results of using them, uncaged, is lots and lots of confabulations that sound like real things, whether they are or not.”

The solution is not to “train” LLM bots with more and more data, in the hope that eventually they will have databases large enough to make their fabrications unnecessary. Brooks thinks this is the wrong approach. The better option is to purpose-build LLMs to fulfill specific needs in specific fields. Bots specialized for software coding, for instance, or hardware design.

“We need guardrails around LLMs to make them useful, and that is where there will be lot of action over the next 10 years,” he writes. “They cannot be simply released into the wild as they come straight from training. … More training doesn’t make things better necessarily. Boxing things in does.”

Brooks’ all-encompassing theme is that we tend to overestimate what new technologies can do and underestimate how long it takes for any new technology to scale up to usefulness. The hardest problems are almost always the last ones to be solved; people tend to think that new technologies will continue to develop at the speed that they did in their earliest stages.

That’s why the march to full self-driving cars has stalled. It’s one thing to equip cars with lane-change warnings or cruise control that can adjust to the presence of a slower car in front; the road to Level 5 autonomy as defined by the Society of Automotive Engineers — in which the vehicle can drive itself in all conditions without a human ever required to take the wheel — may be decades away at least. No Level 5 vehicles are in general use today.

Believing the claims of technology promoters that one or another nirvana is just around the corner is a mug’s game. “It always takes longer than you think,” Brooks wrote in his original prediction post. “It just does.”

Business

Versant launches, Comcast spins off E!, CNBC and MS NOW

Comcast has officially spun off its cable channels, including CNBC and MS NOW, into a separate company, Versant Media Group.

The transaction was completed late Friday. On Monday, Versant took a major tumble in its stock market debut — providing a key test of investors’ willingness to hold on to legacy cable channels.

The initial outlook wasn’t pretty, providing awkward moments for CNBC anchors reporting the story.

Versant fell 13% to $40.57 a share on its inaugural trading day. The stock opened Monday on Nasdaq at $45.17 per share.

Comcast opted to cast off the still-profitable cable channels, except for the perennially popular Bravo, as Wall Street has soured on the business, which has been contracting amid a consumer shift to streaming.

Versant’s market performance will be closely watched as Warner Bros. Discovery attempts to separate its cable channels, including CNN, TBS and Food Network, from Warner Bros. studios and HBO later this year. Warner Chief Executive David Zaslav’s plan, which is scheduled to take place in the summer, is being contested by the Ellison family’s Paramount, which has launched a hostile bid for all of Warner Bros. Discovery.

Warner Bros. Discovery has agreed to sell itself to Netflix in an $82.7-billion deal.

The market’s distaste for cable channels has been playing out in recent years. Paramount found itself on the auction block two years ago, in part because of the weight of its struggling cable channels, including Nickelodeon, Comedy Central and MTV.

Management of the New York-based Versant, including longtime NBCUniversal sports and television executive Mark Lazarus, has been bullish on the company’s balance sheet and its prospects for growth. Versant also includes USA Network, Golf Channel, Oxygen, E!, Syfy, Fandango, Rotten Tomatoes, GolfNow, GolfPass and SportsEngine.

“As a standalone company, we enter the market with the scale, strategy and leadership to grow and evolve our business model,” Lazarus, who is Versant’s chief executive, said Monday in a statement.

Through the spin-off, Comcast shareholders received one share of Versant Class A common stock or Versant Class B common stock for every 25 shares of Comcast Class A common stock or Comcast Class B common stock, respectively. The Versant shares were distributed after the close of Comcast trading Friday.

Comcast gained about 3% on Monday, trading around $28.50.

Comcast Chairman Brian Roberts holds 33% of Versant’s controlling shares.

Business

Ties between California and Venezuela go back more than a century with Chevron

As a stunned world processes the U.S. government’s sudden intervention in Venezuela — debating its legality, guessing who the ultimate winners and losers will be — a company founded in California with deep ties to the Golden State could be among the prime beneficiaries.

Venezuela has the largest proven oil reserves on the planet. Chevron, the international petroleum conglomerate with a massive refinery in El Segundo and headquartered, until recently, in San Ramon, is the only foreign oil company that has continued operating there through decades of revolution.

Other major oil companies, including ConocoPhillips and Exxon Mobil, pulled out of Venezuela in 2007 when then-President Hugo Chávez required them to surrender majority ownership of their operations to the country’s state-controlled oil company, PDVSA.

But Chevron remained, playing the “long game,” according to industry analysts, hoping to someday resume reaping big profits from the investments the company started making there almost a century ago.

Looks like that bet might finally pay off.

In his news conference Saturday, after U.S. Special Forces snatched Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro and his wife in Caracas and extradited them to face drug-trafficking charges in New York, President Trump said the U.S. would “run” Venezuela and open more of its massive oil reserves to American corporations.

“We’re going to have our very large U.S. oil companies, the biggest anywhere in the world, go in, spend billions of dollars, fix the badly broken infrastructure, the oil infrastructure, and start making money for the country,” Trump said during a news conference Saturday.

While oil industry analysts temper expectations by warning it could take years to start extracting significant profits given Venezuela’s long-neglected, dilapidated infrastructure, and everyday Venezuelans worry about the proceeds flowing out of the country and into the pockets of U.S. investors, there’s one group who could be forgiven for jumping with unreserved joy: Chevron insiders who championed the decision to remain in Venezuela all these years.

But the company’s official response to the stunning turn of events has been poker-faced.

“Chevron remains focused on the safety and well-being of our employees, as well as the integrity of our assets,” spokesman Bill Turenne emailed The Times on Sunday, the same statement the company sent to news outlets all weekend. “We continue to operate in full compliance with all relevant laws and regulations.”

Turenne did not respond to questions about the possible financial rewards for the company stemming from this weekend’s U.S. military action.

Chevron, which is a direct descendant of a small oil company founded in Southern California in the 1870s, has grown into a $300-billion global corporation. It was headquartered in San Ramon, just outside of San Francisco, until executives announced in August 2024 that they were fleeing high-cost California for Houston.

Texas’ relatively low taxes and light regulation have been a beacon for many California companies, and most of Chevron’s competitors are based there.

Chevron began exploring in Venezuela in the early 1920s, according to the company’s website, and ramped up operations after discovering the massive Boscan oil field in the 1940s. Over the decades, it grew into Venezuela’s largest foreign investor.

The company held on over the decades as Venezuela’s government moved steadily to the left; it began to nationalize the oil industry by creating a state-owned petroleum company in 1976, and then demanded majority ownership of foreign oil assets in 2007, under then-President Hugo Chávez.

Venezuela has the world’s largest proven crude oil reserves — meaning they’re economical to tap — about 303 billion barrels, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

But even with those massive reserves, Venezuela has been producing less than 1% of the world’s crude oil supply. Production has steadily declined from the 3.5 million barrels per day pumped in 1999 to just over 1 million barrels per day now.

Currently, Chevron’s operations in Venezuela employ about 3,000 people and produce between 250,000 and 300,000 barrels of oil per day, according to published reports.

That’s less than 10% of the roughly 3 million barrels the company produces from holdings scattered across the globe, from the Gulf of Mexico to Kazakhstan and Australia.

But some analysts are optimistic that Venezuela could double or triple its current output relatively quickly — which could lead to a windfall for Chevron.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoHamas builds new terror regime in Gaza, recruiting teens amid problematic election

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoFor those who help the poor, 2025 goes down as a year of chaos

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoInstacart ends AI pricing test that charged shoppers different prices for the same items

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoPodcast: The 2025 EU-US relationship explained simply

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoApple, Google and others tell some foreign employees to avoid traveling out of the country

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoChatGPT’s GPT-5.2 is here, and it feels rushed

-

Health1 week ago

Health1 week agoDid holiday stress wreak havoc on your gut? Doctors say 6 simple tips can help

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week ago‘Unlucky’ Honduran woman arrested after allegedly running red light and crashing into ICE vehicle