Business

‘A Beautiful Place That Has a Dragon’: Where Hurricane Risk Meets Booming Growth

Hurricanes have always struck the shores of the United States.

But in recent decades, the combination of climate change and a growing coastal population has made them far more damaging — particularly in one corner of the Atlantic coast.

These two metros, known for their striking coastlines, have been regularly battered by hurricanes this century.

They also have something else in common: Both are among the fastest-growing coastal metros in the United States since 2000.

The hurricanes keep coming, and the people, too: The fastest-growing places along the Atlantic coast this century are also among the most hurricane-prone.

Between 2016 and 2022, the five hurricanes that hit the Carolinas cost the two states over $33 billion in damages in current dollars, displaced hundreds of thousands of people and led to the deaths of more than 90, government data shows.

There’s every reason to expect more damage in coming years: A warming climate adds moisture to the air, unlocking the potential for wetter and more powerful storms. And rising sea levels make storm surges more damaging and coastal flooding more frequent.

And the newcomers will keep coming: One 2022 study projected that by 2050, population growth will increase the number of Americans exposed to flooding nearly four times as much as climate change will alone.

Simply put, there are many more people living along the paths of hurricanes than ever before. And this booming coastal population is, by many accounts, a larger contributor to rising hurricane risks than climate change.

“It’s always climate change plus something, and we’re moving more people into harm’s way than out,” said Kathie Dello, North Carolina’s state climatologist.

Kure Beach, N.C., at low tide.

Local officials say they are struggling to keep up with the growth. They can try to manage the floodplain, communicate the risks, regulate construction and prepare for disasters. But the one thing they can’t seem to do is stop people from moving here.

Many retirees are drawn to the Carolinas’ beaches and waterways, moderate temperatures and low taxes. Between 1990 and 2020, the number of people 65 and older grew by nearly 450 percent combined in Horry County, S.C., and adjoining Brunswick County, N.C.

When Gail Hart moved from Arizona to retire in Wilmington, N.C., in 2017, she hadn’t considered the hurricane risk. “I wanted to be near a beach,” she said. “I wanted a community.”

Gail Hart with her dog Tula in the Del Webb retirement community in Wilmington, N.C.

The next year, Hurricane Florence made landfall in the Wilmington metro area. Many neighborhoods flooded. In some places, three feet of water entered homes. Emergency officials rescued over a thousand residents.

Ms. Hart evacuated. She was fortunate: Her home suffered only minor wind damage. But the experience changed her view of living there. She installed storm shutters and a generator, and bought flood insurance. And yet, like so many others, she has stayed despite the storm risks.

“I don’t let it affect my life unless there’s a hurricane coming,” she said.

Ms. Hart is far from alone. When she arrived, there were about a dozen homes in her retirement community. Today there are over 500.

In a retirement community being built across the road, acres of pine forests have been cleared to develop homes along the Cape Fear River.

New homes on the banks of the Cape Fear River in Wilmington, N.C.

Nearby, marshland with ghost forests of dead trees was up for sale as “riverfront condo land.”

Ghost forests are what remains of woodlands when saltwater poisons the roots of trees.

Wilmington is part of New Hanover County, the most densely populated of the state’s coastal counties. Nearly 40 percent of its homes risk being severely affected by flooding in the next 30 years, according to the First Street Foundation.

“There’s just not a lot of area left,” said Steven Still, director of emergency services for the county. “So you’re developing in the fringe areas.”

The escalating costs of storms raise a difficult question for these growing coastal communities: How do you balance growth with safety?

The combination of climate change and development in risky areas is making it “a huge challenge” to keep residents safe, said Amanda Martin, North Carolina’s chief resilience officer.

Hurricanes near U.S. counties, 1950-2022

Coastal Carolina counties have some of the highest hurricane frequencies in the country.

Source: Upshot analysis of the National Hurricane Center’s Atlantic hurricane database

The map shows the number of Atlantic hurricanes whose paths came within 60 nautical miles (69 miles) of each county.

It’s not just that people are moving to hurricane-prone areas. The growth itself can make flooding worse. Cutting down trees and paving over wetlands takes away open land that would otherwise absorb rainfall.

“We just seem to be going through this vicious cycle that is becoming more vicious with the amount of people and infrastructure we put in these areas,” Mr. Still said.

Federal law permits people to build in flood zones, so long as they meet certain minimum standards. In return, the government offers them flood insurance through a federal program that is over $20 billion in debt — largely due to escalating hurricane damages.

While the National Flood Insurance Program was originally intended to discourage floodplain development, in practice it has done the opposite by removing a lot of the financial risk involved, said Jenny Brennan, a climate analyst at the Southern Environmental Law Center.

States have a few options to discourage people from building in flood zones. They can create more stringent building requirements, or they can buy up and preserve undeveloped land. But these measures are expensive, and rely on political will or the willingness of landowners to sell.

One way that states can move residents out of harm’s way is by offering to buy out their homes and permanently converting that land to open space. But a study this year found that for every home bought out in North Carolina between 1996 and 2017, more than 10 new ones were built in the state’s floodplains.

The growth also makes it more difficult to evacuate when storms strike. In these booming coastal counties, residents and local officials say that roads and bridges are not keeping pace with the growth.

“Our biggest problem is our infrastructures not being able to keep up,” said David McIntire, the deputy director of emergency management for Brunswick County, the fastest-growing coastal county in North Carolina this century and part of the Wilmington metro.

The state has undertaken a multiyear project to add two lanes to Highway 211, the main evacuation route for the region. Mr. McIntire said the state and local departments were “having to play catch-up” after years of failing to plan ahead.

In neighboring New Hanover County, his counterpart Mr. Still is grappling with a shortage of affordable housing, which he said was making it “exponentially difficult” to shelter people displaced by disasters.

After a disaster, the surge in demand for short-term housing drives up already high rents. Poorer residents often rely on the state and local governments for assistance with evacuation and housing.

The problem lies in where to house them. “If there is zero housing availability in the community right now,” Mr. Still said, “where do you put 100,000 people?”

The housing crunch is one of many tensions playing out between wealthy coastal communities and those who live nearby.

April O’Leary lives in Conway, S.C., an inland city in Horry County, a half-hour drive from Myrtle Beach.

The county makes up the Myrtle Beach metro area, which was the fastest-growing coastal metro nationally between 2000 and 2020 and is one of the fastest-growing places in the country annually. And the growth is projected to continue.

Horry County is large and flat: Nearly a quarter of its land lies within a floodplain.

In inland towns like Conway, S.C., floodwaters can stay long after a hurricane is gone.

After Hurricane Florence made landfall, it took about a week for the rainwater to flow down to Conway. But the water stayed for over a week.

“It sits for a while and it just destroys everything,” Ms. O’Leary said.

Water entered her home, flooding the first floor and a bedroom. Her husband and son evacuated to Myrtle Beach, while she stayed for a few days to document the floods.

Afterward, there were large piles of debris lining street after street in her neighborhood, filled with ruined flooring, kitchen cabinets and bathroom fixtures.

When her son’s elementary school reopened and he saw the devastation in the neighborhood, she said he stopped smiling and became quieter for months.

Down the street from April O’Leary’s home, in Conway, S.C., the flood water line from Hurricane Florence was still visible.

After the flooding, Ms. O’Leary founded Horry County Rising, a political organization that campaigned for the county to adopt stricter regulations for floodplain construction. Much of the flooding in the Carolinas during Hurricane Florence occurred outside of federal flood zones, where few people have flood insurance or homes that are protected from flooding.

In 2021, the county expanded its flood zone boundaries to include places that flooded during Hurricane Florence. And it required new homes built there to have their lowest floor three feet above the high water mark.

The changes applied to all unincorporated parts of the county. But they faced pushback from local developers because of raised building costs. The county recently voted to lower the height requirements to two feet, after legal pressure from a developer.

The flooding and growth also affect rural communities that have been rooted in the Carolinas for generations. In Bucksport, S.C., a small inland town in Horry County, Kevin Mishoe is a third-generation farmer and former chair of the Association for the Betterment of Bucksport.

He said the newer building codes would pay dividends in future floods, but they would also make home ownership far more expensive for people in lower-income communities like Bucksport.

Bucksport sits between two major rivers, nestled against wetlands and tidal forests. Mr. Mishoe lives with his wife in a mobile home that flooded during Hurricane Matthew in 2016 and Hurricane Florence in 2018.

Gina and Kevin Mishoe outside their home in Bucksport, S.C.

Mr. Mishoe says he believes banks are denying loans to residents because of their location in a floodplain, a phenomenon he called “bluelining.”

Meanwhile, he said, locals are being “bombarded” with offers from developers and private equity companies to buy their land.

“All of a sudden land that you’re telling us is almost worthless because you’re in a flood zone, everybody’s trying to buy,” he said.

The area is considered prime real estate because of its access to water. This year, the county expressed support for a highway that would connect Myrtle Beach to inland parts of the county. The highway is expected to cut through Bucksport and its adjoining wetlands, and bring added development to the region.

The town’s residents emphatically do not want to sell their land, Mr. Mishoe said. Their ancestors have held on to this land for generations, and they intend to stay.

Bucksport’s flooding problem began in 2015. But there are coastal Carolina communities that have endured regular hurricanes for over a century.

Karen Willis Amspacher lives on Harkers Island in Carteret County, N.C. — one of the most hurricane-prone counties in the country.

The island is part of a string of low-lying rural communities near the Outer Banks that locals call Down East. The communities are connected by Highway 70, a dredged road that floods several times a year.

Highway 70 outside Stacy, N.C., in Carteret County.

Ms. Amspacher is a fifth-generation resident of the island and the director of the Core Sound Waterfowl Museum. There are a lot of newer residents, she said, moving into large houses on stilts, with generators and flood insurance. Some houses are second homes or vacation properties.

The construction boom has driven up costs for locals. “The fear and threat of sea level rise or storms doesn’t hinder any of it,” she said.

A raised home under construction on Harkers Island, N.C.

A new bridge under construction earlier this year will connect Harkers Island to the mainland, to improve evacuations during hurricanes.

While the new homes may be safer, Ms. Amspacher said, many of the newcomers are isolated from the emotional trauma that her community experiences during a hurricane.

“This is a piece of property to them,” she said. “It’s not their family inheritance. It’s not their home. It’s not where they hope their children will stay and grow up.”

Ms. Amspacher has had to evacuate her home in three past hurricanes. But she’s not planning to leave for the next one. She said staying during storms was a way to protect property from damage, and was part of her community’s cultural identity.

“These hurricanes make these communities what we are,” she said.

Back in Wilmington, Sharon Valentine is also no stranger to hurricanes. She owned a large animal farm near Fayetteville, N.C., which was devastated by Hurricane Fran in 1996.

So when she and her partner decided to retire in Wilmington’s Del Webb community in 2017, they knew the risks.

Many others have followed since. “There’s a mass migration down here,” she said.

Ms. Valentine organizes annual hurricane training for these newer arrivals. The community members have evacuation plans and look out for one another.

Sharon Valentine and Leonard Bull keep an emergency go bag, which they call a “calamity box,” at their home in Wilmington.

She, too, said the local infrastructure hadn’t kept up with growth. There are two small bridges on either end of River Road that serve as the main evacuation routes for her community. She is concerned that they may flood in a major storm.

“If we really ever have a bad one, we’re going to have to get out of here,” Ms. Valentine said.

Still, when she thinks about all the newcomers, she sympathizes with their reasons for moving here.

“It is a beautiful place that has a dragon emerge periodically,” she said. “And so you weigh your risks.”

Business

Paramount chair Shari Redstone has been diagnosed with thyroid cancer

Paramount Global chairwoman and controlling shareholder Shari Redstone is battling cancer as she tries to steer the media company through a turbulent sales process.

“Shari Redstone was diagnosed with thyroid cancer earlier this spring,” her spokeswoman Molly Morse said late Thursday. “While it has been a challenging period, she is maintaining all professional and philanthropic activities throughout her treatment, which is ongoing.

“She and her family are grateful that her prognosis is excellent,” Morse said.

The news comes nearly 11 months after Redstone agreed to sell Paramount to David Ellison’s Skydance Media in a deal that would end the family’s tenure as major Hollywood moguls.

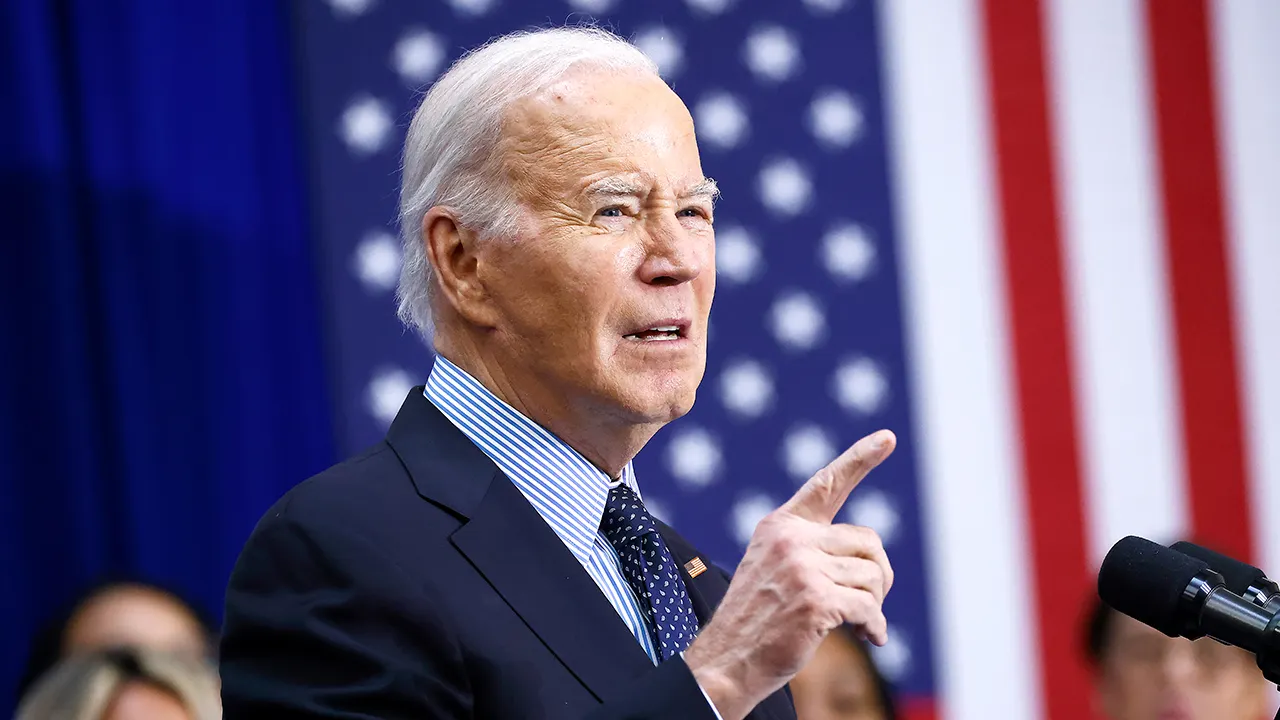

However, the government’s review of the Skydance sale hit a snag amid President Trump’s $20-billion lawsuit against Paramount subsidiary CBS over edits to an October “60 Minutes” broadcast.

Redstone, 71, told the New York Times that she underwent surgery last month after receiving the diagnosis about two months ago. Surgeons removed her thyroid gland but did not fully eradicate the cancer, which had spread to her vocal cords, the paper said.

She continues to be treated with radiation, the paper reported.

The Redstone family controls 77% of the voting shares of Paramount. Her father, the late Sumner Redstone, built the company into a juggernaut but it has seen its standing slip in recent years. There have been management missteps and pressures brought on by consumers’ shift to streaming. The trend has crimped revenue to companies that own cable channels, including Paramount.

Redstone has wanted to settle the lawsuit Trump filed in October, weeks after “60 Minutes” interviewed then-Vice President Kamala Harris. Trump accused CBS of deceptively editing the interview to make Harris look smarter and improve her election chances, a charge that CBS has denied.

The dispute over the edits has sparked unrest within the company, prompted high-level departures and triggered a Federal Communications Commission examination of alleged news distortion.

The FCC’s review of the Skydance deal has become bogged down. If the agency does not approve the transfer of CBS television station licenses to the Ellison family, the deal could collapse.

The two companies must complete the merger by early October. If not, Paramount will owe a $400-million breakup fee to Skydance. Redstone, through the family’s National Amusements Inc., also owes nearly $400 million to a Chicago banker and tech titan Larry Ellison, who is helping bankroll the buyout of Paramount and National Amusements.

Business

How Hard It Is to Make Trade Deals

President Trump has announced wave after wave of tariffs since taking office in January, part of a sweeping effort that he has argued would secure better trade terms with other countries. “It’s called negotiation,” he recently said.

In April, administration officials vowed to sign trade deals with as many as 90 countries in 90 days. The ambitious target came after Mr. Trump announced, and then rolled back a portion of, steep tariffs that in some cases meant import taxes cost more than the wholesale price of a good itself.

The 90-day goal, however, is a tenth of the time it usually takes to reach a trade deal, according to a New York Times analysis of major agreements with the United States currently in effect, raising questions about how realistic the administration’s target may be. It typically takes 917 days, or roughly two and a half years, for a trade deal to go from initial talks to the president’s desk for signature, the analysis shows.

Roughly 60 days into the current process, Mr. Trump has so far announced only one deal: a pact with Britain, which is not one of America’s biggest trading partners.

He has also suggested that negotiations with China have been rocky. “I like President XI of China, always have, and always will, but he is VERY TOUGH, AND EXTREMELY HARD TO MAKE A DEAL WITH!!!” Mr. Trump wrote on Truth Social on Wednesday. China and the United States agreed last month to temporarily slash tariffs on each other’s imports in a gesture of good will to continue talks.

Part of what the president can accomplish boils down to what you can call a deal.

The pact with Britain is less of a deal than it is a framework for talking about a deal, said Wendy Cutler, the vice president of the Asia Society Policy Institute and a former U.S. trade negotiator. What was officially released by the two nations more closely resembled talking points for “what you were going to negotiate versus the actual commitment,” she said.

During his first term, Mr. Trump secured two major trade agreements, both signed in January 2020. One was the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement, which was a reworking of the North American free trade treaty from the 1990s that had helped transform the economies of the three nations.

U.S.M.C.A. is an all-encompassing, legally binding agreement that resulted from a lengthy and formal process, according to trade analysts.

Such deals are supposed to cover all aspects of trade between the respective nations and are negotiated under specific guidelines for congressional consultation. Closing the deal involves both negotiation and ratification — modifying or making laws in each partner country. The deals are signed by trade negotiators before the president signs the legislation that puts it into effect for the United States.

Mr. Trump’s other major agreement in his first term was with China, in an echo of the current trade war. The pact, unlike previous deals, came about after Mr. Trump threatened tariffs on certain Chinese imports. This “tariff first, talk later” approach, said Inu Manak, a trade policy fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations, is part of the same playbook the administration is currently using.

The result was a nonbinding agreement between the two countries, known as “Phase One,” that did not require approval from Congress and that could be ended by either party at any time. Still, it took almost one year and nine months to complete. China ultimately fell far short of the commitments it made to purchase American goods under the agreement.

A comparison of the two first-term Trump deals shows the drawn-out and sometimes winding paths each took to completion. Fragile truces (including ones made for 90 days) were formed, only for talks to break down later, all while rounds of tariffs injected uncertainty into the diplomatic relations between countries.

The Times analysis used the date from the start of negotiations to the date when the president signed to determine the length of deal making for each major agreement dating back to 1985 that’s currently in effect. The median time it took to get to the president’s signature was just over 900 days. (A separate analysis published in 2016 by the Peterson Institute for International Economics used the date of signature by country representatives as the completion moment and found that the median deal took more than 570 days.)

With roughly one month before the administration’s self-imposed deadline, Mr. Trump’s ability to forge deals has been thrust into sudden doubt. Last week, a U.S. trade court ruled he had overstepped his authority in imposing the April tariffs.

For now, the tariffs remain in place, following a temporary stay from a federal appeals court. But in arguing its case, the federal government initially said that the ruling could upset negotiations with other nations and undercut the president’s leverage.

In a statement on Wednesday, Kush Desai, a White House spokesman, said that trade negotiators were working to secure “custom-made trade deals at lightning speed that level the playing field for American industries and workers.”

But in other recent public statements, White House officials have significantly pared back their ambitions for the deals.

In April, Scott Bessent, the Treasury secretary, hedged the number of agreements they might reach, suggesting that the United States would talk to somewhere between 50 and 70 countries. Last month he said the United States was negotiating with 17 “very important trading relationships,” not including China.

“I think when the administration first started, they thought they could actually do these binding and enforceable deals within 90 days and then quickly realized that they bit off more than they could chew,” Ms. Cutler said.

The administration told its negotiating partners to submit offers of trade concessions they were willing to make by Wednesday, in an effort to strike trade deals in the coming weeks. The deadline was earlier reported by Reuters.

The current approach to deal making may be strategic, Ms. Manak said. One of the benefits of not doing a comprehensive deal like U.S.M.C.A. is that the administration can declare small “victories” on a much faster timeline, she said.

“It means that trade agreements simply are just not what they used to be,” she added. “And you can’t really guarantee that whatever the U.S. promises is actually going to be upheld in the long run.”

Data and graphics are based on a New York Times analysis of information from the Congressional Research Service, the U.S. Trade Representative, the Organization of American States’ Foreign Trade Information System and public White House communications.

Business

Terranea Resort accused of pregnancy discrimination, retaliation in lawsuit

A former marketing executive at the Terranea Resort sued the luxury establishment on Wednesday, alleging its president had made discriminatory comments towards pregnant women working at the company.

The former marketing exercutive, Chad Bustos, alleges in the lawsuit filed on Wednesday that he was fired in retaliation after he defended several female employees.

Terranea Resort and the company’s president did not respond to a request for comment about allegations in the lawsuit, which was filed in Los Angeles County Superior Court.

Bustos said he had worked at the 560-room oceanfront resort that perches on the Palos Verdes Peninsula since 2023. He had supervised an all-female marketing team, of which three employees were young moms with children under 3, according to the complaint.

The lawsuit describes a meeting in February 2024, where the resort’s president, Ralph Grippo, became “visibly angry” after hearing a woman on the team planned to take maternity leave. Her announcement had come months after another employee had returned from maternity leave.

Grippo, who also is a defendant in the lawsuit, allegedly stood up, pushed his chair back and began questioning the other women in the room. The lawsuit said Grippo pointed at each woman in turn, asking, “Are you pregnant?” After each woman answered, he sat back down and the meeting continued.

After the meeting, Grippo allegedly began “scrutinizing the marketing team and nitpicking their performance,” using the resort’s security cameras to see what time they arrived to work and when they left. He told Bustos to write up the women for what he deemed to be minor infractions, but Bustos refused, according to the complaint.

At another meeting in May 2024, Grippo scolded female employees for not working hard enough, although the team was high-performing and employees worked long hours, the lawsuit said.

Grippo was reported to the human resources department by one of the women, and Bustos confirmed her claims to the department, the lawsuit said. Bustos also confronted Grippo around that time, telling him his comments were inappropriate, according to the complaint.

After that, Grippo refused to speak with Bustos or return his calls, the lawsuit alleged, and in August 2024, Grippo fired Bustos.

Under California law, it is illegal for employers to ask employees about medical conditions, including pregnancy.

And anti-pregnancy comments can be used as evidence of sex discrimination, said Lauren Teukolsky, the attorney representing Bustos.

Bustos, who had worked with Grippo for 11 years at another company prior to joining him at the Terranea Resort, said in an interview that he initially thought Grippo would understand his perspective because of their long-standing relationship.

Bustos said his team was “very talented and hardworking,” and the sacrifices they and others have made to raise children “should be important for everybody.”

Grippo had had a history of making other anti-pregnancy comments, the lawsuit alleged.

When a woman asked Grippo for a promotion, he allegedly questioned her about how she planned to balance the promotion while raising a child. He asked another woman with two children who applied for a marketing job if her work schedule was going to be a problem since she was a mom, the lawsuit said.

Grippo wrote up another pregnant employee because she came in 15 minutes late as a result of morning sickness, and questioned another pregnant employee why she had so many doctor’s appointments, the lawsuit said.

In 2017, former dishwasher and chef assistant Sandra Pezqueda sued the resort and a staffing agency after she allegedly experienced repeated sexual harassment and assault by her supervisor, who then retaliated against her by changing her work schedule after she rejected his advances.

Pezqueda received a $250,000 settlement with the company denying any wrongdoing, news reports said.

Then-president Terri A. Haack said in a statement to Time that the company has “a zero-tolerance policy toward harassment.”

The Terranea resort is jointly owned by JC Resorts, a company with a portfolio of resorts and golf courses based in La Jolla, and Lowe Enterprises, real estate investment firm based in Los Angeles. The companies did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoTrump admin asking federal agencies to cancel remaining Harvard contracts

-

Culture1 week ago

Culture1 week agoCan You Match These Canadian Novels to Their Locations?

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoThe Browser Company explains why it stopped developing Arc

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoHarvard's president speaks out against Trump. And, an analysis of DEI job losses

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoRead the Trump Administration Letter About Harvard Contracts

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoVideo: Faizan Zaki Wins Spelling Bee

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoDrone war, ground offensive continue despite new Russia-Ukraine peace push

-

Politics5 days ago

Politics5 days agoMichelle Obama facing backlash over claim about women's reproductive health