Science

California issues advisory on a parasitic fly whose maggots can infest living humans

A parasitic fly whose maggots can infest living livestock, birds, pets and humans could threaten California soon.

The New World Screwworm has rapidly spread northward from Panama since 2023 and farther into Central America. As of early September, the parasitic fly was present in seven states in southern Mexico, where 720 humans have been infested and six of them have died. More than 111,000 animals also have been infested, health officials said.

In early August, a person traveling from El Salvador to Maryland was discovered to have been infested, federal officials said. But the parasitic fly has not been found in the wild within a 20-mile radius of the infested person, which includes Maryland, Virginia and the District of Columbia.

After the Maryland incident, the California Department of Public Health decided to issue a health advisory this month warning that the New World Screwworm could arrive in California from an infested traveler or animal, or from the natural travel of the flies.

Graphic images of New World Screwworm infestations show open wounds in cows, deer, pigs, chickens, horses and goats, infesting a wide swath of the body from the neck, head and mouth to the belly and legs.

The Latin species name of the fly — hominivorax — loosely translates to “maneater.”

“People have to be aware of it,” said Dr. Peter Chin-Hong, a UC San Francisco infectious diseases specialist. “As the New World Screwworm flies northward, they may start to see people at the borders — through the cattle industry — get them, too.”

Other people at higher risk include those living in rural areas where there’s an outbreak, anyone with open sores or wounds, those who are immunocompromised, the very young and very old, and people who are malnourished, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says.

There could be grave economic consequences should the New World Screwworm get out of hand among U.S. livestock, leading to animal deaths, decreased livestock production, and decreased availability of manure and draught animals, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

“It is not only a threat to our ranching community — but it is a threat to our food supply and our national security,” the USDA said.

Already, in May, the USDA suspended imports of live cattle, horse and bison from the Mexican border because of the parasitic fly’s spread through southern Mexico.

The New World Screwworm isn’t new to the U.S.

But it was considered eradicated in the United States in 1966, and by 1996, the economic benefit of that eradication was estimated at nearly $800 million, “with an estimated $2.8 billion benefit to the wider economy,” the USDA said.

Texas suffered an outbreak in 1976. A repeat could cost the state’s livestock producers $732 million a year and the state economy $1.8 billion, the USDA said.

Historically, the New World Screwworm was a problem in the U.S. Southwest and expanded to the Southeast in the 1930s after a shipment of infested animals, the USDA said. Scientists in the 1950s discovered a technique that uses radiation to sterilize male parasitic flies.

Female flies that mate with the sterile male flies produce sterile eggs, “so they can’t propagate anymore,” Chin-Hong said. It was this technique that allowed the U.S., Mexico and Central America to eradicate the New World Screwworm by the 1960s.

But the parasitic fly has remained endemic in South America, Cuba, Haiti and the Dominican Republic.

In late August, the USDA said it would invest in new technology to try to accelerate the pace of sterile fly production. The agency also said it would build a sterile-fly production facility at Edinburg, Texas, which is close to the Mexico border, and would be able to produce up to 300 million sterile flies per week.

“This will be the only United States-based sterile fly facility and will work in tandem with facilities in Panama and Mexico to help eradicate the pest and protect American agriculture,” the USDA said.

The USDA is already releasing sterile flies in southern Mexico and Central America.

The risk to humans from the fly, particularly in the U.S., is relatively low. “We have decent nutrition; people have access to medical care,” Chin-Hong said.

But infestations can happen. Open wounds are a danger, and mucus membranes can also be infested, such as inside the nose, according to the CDC.

An infestation occurs when fly maggots infest the living flesh of warm-blooded animals, the CDC says. The flies “land on the eyes or the nose or the mouth,” Chin-Hong said, or, according to the CDC, in an opening such as the genitals or a wound as small as an insect bite. A single female fly can lay 200 to 300 eggs at a time.

When they hatch, the maggots — which are called screwworms — “have these little sharp teeth or hooks in their mouths, and they chomp away at the flesh and burrow,” Chin-Hong said. After feeding for about seven days, a maggot will fall to the ground, dig into the soil and then awaken as an adult fly.

Deaths among humans are uncommon but can happen, Chin-Hong said. Infestation should be treated as soon as possible. Symptoms can include painful skin sores or wounds that may not heal, the feeling of the larvae moving, or a foul-smelling odor, the CDC says.

Patients are treated by removal of the maggots, which need to be killed by putting them into a sealed container of concentrated ethyl or isopropyl alcohol then disposed of as biohazardous waste.

The parasitic fly has been found recently in seven Mexican states: Campeche, Chiapas, Oaxaca, Quintana Roo, Tabasco, Veracruz, and Yucatán. Officials urge travelers to keep open wounds clean and covered, avoid insect bites, and wear hats, loose-fitting long-sleeved shirts and pants, socks, and insect repellents registered by the Environmental Protection Agency as effective.

Science

Fed up with perimenopause or menopause? The We Do Not Care Club is here for you

Melani Sanders is over it.

She’s over meticulously applying makeup before leaving the house or, even, having to wear a bra when running errands. She’s over wasting time plucking chin hairs, searching for brain fog-induced lost reading glasses and — most of all — withholding her opinions so as not to offend others.

As a 45-year-old perimenopausal woman, Sanders is no longer searching for outside validation and is over people-pleasing.

The dedication page in her new book sums it up best: “To the a— who told me I had a “computer box booty.”

Who is this dude, and is Sanders worried about offending him?

She doesn’t care.

Author, Melani Sanders, in an outfit she typically wears in her social media videos.

(Surej Kalathil Sunman Media)

That’s Sanders’ mantra in life right now. Last year, the West Palm Beach, Fla.-based mother of three founded the We Do Not Care Club, an online “sisterhood” into the millions of perimenopausal, menopausal and post-menopausal women “who are putting the world on notice that we simply do not care much anymore.” Sanders’ social media videos feature her looking disheveled — in a bathrobe and reading glasses, for example, with additional pairs of reading glasses hanging from her lapels — while rattling off members’ comments about what they do not care about anymore.

“We do not care if we still wear skinny jeans — they stretch and they’re comfortable,” she reads, deadpan. “We do not care if the towels don’t match in our house — you got a rag and you got a towel, use it accordingly.”

Sanders’ online community of fed up women grew rapidly. She announced the club in May 2025, and it has more than 3 million members internationally; celebrity supporters include Ashley Judd, Sharon Stone and Halle Berry. It’s a welcoming, if unexpected, space where women “can finally exhale,” as Sanders puts it. The rallying cry? “We do not give a f—ing s— what anyone thinks of us anymore.”

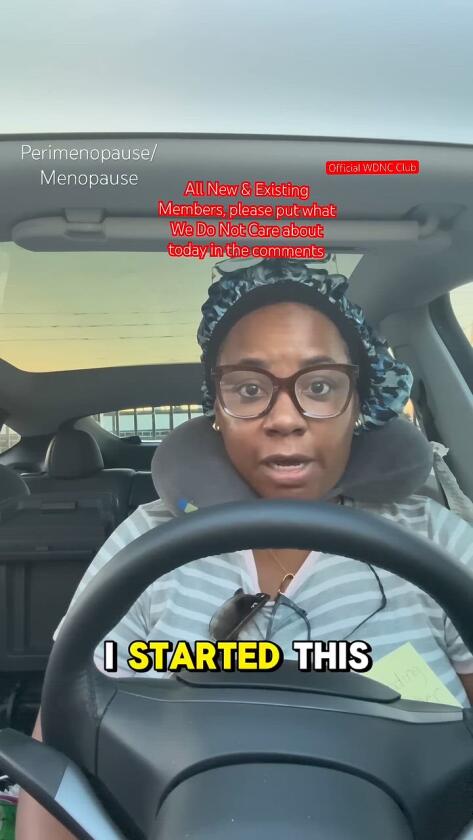

That’s also the message of Sanders’ new book, “The Official We Do Not Care Club Handbook: A Hot-Mess Guide for Women in Perimenopause, Menopause, and Beyond Who Are Over It.” The book is part self-help book, with facts about the perimenopause and menopause transition; part memoir; part practical workbook with tools and resources; and part humor book, brimming with Sanders’ raw and authentic comedic style. (It includes a membership card for new club inductees and cutout-able patches with slogans like “lubricated and horny” or “speaking your truth.”)

We caught up with Sanders while she was in New York to promote her book and admittedly “overstimulated from all the horns,” she said. But she just. Did. Not. Care.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

The We Do Not Care Club came about after you had a meltdown in a supermarket parking lot. Tell us about that.

I was in the parking lot of Whole Foods. I needed Ashwagandha — that was my holy grail at the time for my perimenopause journey, and I was out of it. I got back in my car and looked at myself in the rear view mirror. I had on a sports bra that was shifted to one side. My hair was extremely unstructured. I had a hat on and socks mismatched — I was a real hot mess. Nothing added up. But in that moment, I realized that I just didn’t care much anymore. I just said, “Melanie, you have to take the pressure off, girlfriend. It’s time to stop caring so much.” I decided to press the record button and see if anyone wanted to join me in starting a club called the We Do Not Care Club. I released the video and drove home, which took about 20 minutes, and by the time I got home it had [gone viral].

You got hundreds of thousands of new followers, internationally, within 24 hours. Why do you think the post resonated so greatly at that moment?

I had to dissect that because it was kind of unreal. Like, what is it about country, old Melanie that hit record and asked about a little club that she thought maybe 20 or 30 women would want to join? Over the summer, I studied this and did more videos and I listened. It was the relatability. It was the understanding. It was just letting my guard down and just saying it out loud. Speaking my truth. Also, for many women, we have this silent pressure to get it all done. But we’re at capacity. In the book, I talk about how, once I was in perimenopause, I didn’t want to have sex with my husband. I didn’t want to see my kids — like, everyone just close the door! And that’s kind of shameful, you know? It’s not like I don’t love my family. I really do. But I can’t do it all anymore. And I just think that resonated with a lot of sisters throughout the world. It was like: Now is the time for us to just explode and I think we all did it at once.

“The Official We Do Not Care Club Handbook.”

(William Morrow)

You entered perimenopause (or “Miss Peri,” as you call it) at age 44, after a partial hysterectomy. How did your life change after that?

I did not expect it. I knew that I had fibroids and I was uncomfortable because of that. So when I had the hysterectomy, I was expecting to now be a whole person again afterwards. But I just went into this dark place. It was like you’re fighting against yourself to just be normal again. And your body is changing in so many ways. For me, that was the hot flashes, the insomnia, the depression, the rage. My joints were really, really stiff all of a sudden. It’s like, ‘wait a minute, how and why?!!’ And [I got] frozen shoulder. Frozen shoulder was how I discovered I was in perimenopause because I was not told by my doctor who performed my hysterectomy that this could happen. And I didn’t know where to turn or where to go because I was just being told everything was normal. I was so frustrated with the process, the lack of education, the lack of resources. The lack of compassion, I would even say.

Your book and social media videos are so funny. Do you have a comedy background?

I don’t, and I get asked that often. I just say what’s on my mind and sometimes, I guess, it comes out funny — but I’m not trying. The [wearing multiple pairs of] glasses: I do that because, with perimenopause, my eyesight went bad really quickly. I was out in public one day and I could not read. I was just traumatized. So every time I would see glasses, I would just put them on me because I don’t want to get stuck without them. That neck pillow, when I got frozen shoulder, I was using it a lot. Then one day when I hit record, I had the neck pillow on and I just didn’t care. And it stuck.

You’ve appeared on TV, been featured in publications, and People magazine named you creator of the year for 2025. What has this sudden fame been like for you?

It’s surreal. I have not completely processed it yet. It’s a lot to take in. I’m just an everyday woman that decided to press record and accidentally started a movement. Impostor syndrome is there from time to time. But I’m just trying my best to accept everything that’s going on — and keep just being Melani.

Has the overwhelming response from new members fueled your own resolve to be true to yourself or otherwise changed you personally?

It absolutely has. It’s the strength that the sisterhood gives me. Because I’m very scared. You know, the book is coming out. And the tour is sold out in several cities. This is all within an eight-month span. It’s a lot. But when everyone is saying they love you, and when you have a group of women that understands you and feels the way that you feel, absolutely, there’s strength in numbers. Now I don’t care about making mistakes.

You live in a very male household. What do your sons and husband think of all this?

Once I decided that I didn’t care anymore, I just expected for them to kind of allow things just to go to hell around the house — but it was quite the opposite. All three of my sons and my husband, they’re just very supportive. Because it was very sad for me. It was very hard to not want to watch movies or anything and just be by myself. But they rose to the occasion and they make sure things are done when they’re home. They really show how they love their mom during this time.

How can other men become allies to the women they love during the menopause transition?

Just either get out of our way or, you know, just kind of read the room! Because we don’t know who we are from day to day. We don’t know what’s gonna ache. We don’t know what’s going to hurt or what’s going to itch or what’s going to be dry. And if it’s an off day, then darling, it’s just an off day — and it’s OK.

What are some things that you do still care about greatly?

I care about sisterhood. Because when women bind together, it’s a game changer. We will move mountains. I just think that, in this world, there’s so much pressure, so much overstimulation. So I care about being able to live authentically. To feel free. To be OK with who you are. Within WDNC, the two things that I definitely want to convey that I care about is: that you are enough. And you are not alone. And of course I love my kids. I love my family immensely.

Where does the WDNC go from here? What’s the future?

Retreats. That is definitely a dream. To have a weekend retreat where women can come and the only thing that you need to bring is some clean underwear and some pantyliners! (You can’t have a good, hard laugh or a good sneeze or a good cough without pissing your pants.) No makeup, no nothing, just come and be free. I want three different rooms. One will be the rage room and you’ll go in there and just throw stuff around and scream and punch, whatever you want. Then a quiet room. No talking, no nothing, just silence. And the last room will be the “Let that s— go room.” That’s where we’ll put everything that we have in us, that we’re holding onto that’s keeping us from living a blissful and peaceful life, and write it down and let it go. I just want to touch sisters and let them know it is OK. We are OK. I have my s— I go through. You have your s— you go through. It’s OK. Let’s live.

Science

‘It is scary’: Oak-killing beetle reaches Ventura County, significantly expanding range

A tiny beetle responsible for killing hundreds of thousands of oak trees in Southern California has reached Ventura County, marking a troubling expansion.

This is the farthest north the goldspotted oak borer has been found in the state. Given the less-than-one-half-inch insect’s track record of devastating oaks since being first detected in San Diego County in 2008, scientists and land stewards are alarmed — and working to contain the outbreak.

“We keep seeing these oak groves getting infested and declining, and a lot of oak mortality,” said Beatriz Nobua-Behrmann, an ecologist with UC Agriculture and Natural Resources. “And as we go north, we have tons of oak woodlands that are very important ecosystems over there. It can even get into the Sierras if we don’t stop it. So it is scary.”

A goldspotted oak borer emerges from a tree.

(Shane Brown)

Although officials are only now reporting the arrival, they first found the beetle in Ventura County in the summer of 2024. Julie Clark, a community education specialist at the UC program, recalled getting a call from a local forester who spotted an unhealthy-looking coast live oak while driving in the Simi Hills’ Box Canyon.

“He saw dieback. He saw all the leaves on the crown were brown, which is one of the characteristic signs of a GSOB infestation,” Clark said in a blog post published this week, using the acronym for the invasive insect.

The forester examined the tree and found D-shaped holes — the calling card of the goldspotted oak borer — where the beetles had chewed through the tree to emerge from the bark.

Foresters debarked and chipped the highly infested tree to kill the beetles inside. Surrounding trees, however, were not afflicted.

Still, the beetle continued its march in the county. In April, another dead, beetle-infested oak was found in Santa Susana, according to the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection. A month later, several more dead and injured trees were discovered.

The beetle, named for six gold spots that adorn its back, doesn’t fly far. It reaches faraway areas by hitching a ride on firewood. Nobua-Behrmann, an urban forestry and natural resources advisor, is among a contingent calling for regulations limiting the movement of firewood.

The goal, they say, is to prevent the slaughter of the state’s iconic oaks.

The beetles lay their eggs on oaks. When the larvae hatch, they bore in to reach the cambium. The cambium is like a tree’s blood vessels, carrying water and nutrients up and down. The insect chews through the layer, and eventually the damage is akin to putting a permanent tourniquet on the tree.

An infested tree will often display a thinning canopy and red or black stains on the trunk, injured areas where the tree is attempting to force out insects. The “confirming sign” is the roughly eighth-inch exit hole.

In the Golden State, the beetles are attacking the coast live oak, canyon live oak and the California black oak.

The goldspotted oak borer is native to Arizona, where the ecosystem is adapted to it and it doesn’t kill many trees. It’s believed that it traveled to San Diego County via firewood. It has since been found in L.A., Orange, Riverside and San Bernardino counties, and, according to research by UC Riverside, has killed an estimated 200,000 oak trees.

In 2024, the beetle was discovered in several canyons in Santa Clarita, putting it just 14 miles from the roughly 600,000 coast live oaks in the Santa Monica Mountains. Reaching the scenic coastal mountain range was described as “the worst case scenario” for L.A. County in a 2018 report.

Researchers, fire officials and land managers, among others, are working to control or slow the beetles’ death march. They acknowledge they’re unlikely to be eradicated in the areas where they’ve settled in.

Experts advise removing and properly disposing of heavily infested trees, and that entails chipping them. (To kill the minute beetle, chips must be 3 inches in diameter or smaller.)

If trees are lightly or not yet infested, they can be sprayed or injected with insecticides.

However, there are drawbacks to the current options. Pesticides may harm nontarget species, such as butterflies and moths. And the treatment can be expensive and laborious, making it impractical for vast swaths of forest.

There’s another nontoxic tactic in play: educating the public to report possible infestations and burn firewood where they buy it.

People can also volunteer to survey trees for signs of the dreaded beetle, allowing them to “do something instead of just worrying about it,” Nobua-Behrmann said.

UC Agriculture and Natural Resources, along with the Cal Fire, is hosting a “GSOB Blitz” surveying event next month in Simi Valley.

Science

With a nudge from industry, Congress takes aim at California recycling laws

The plastics industry is not happy with California. And it’s looking to friends in Congress to put the Golden State in its place.

California has not figured out how to reduce single-use plastic. But its efforts to do so have created a headache for the fossil fuel industry and plastic manufacturers. The two businesses are linked since most plastic is derived from oil or natural gas.

In December, a Republican congressman from Texas introduced a bill designed to preempt states — in particular, California — from imposing their own truth-in-labeling or recycling laws. The bill, called the Packaging and Claims Knowledge Act, calls for a national standard for environmental claims on packaging that companies would voluntarily adhere to.

“California’s policies have slowed American commerce long enough,” Rep. Randy Weber (R-Texas) said in a post on the social media platform X announcing the bill. “Not anymore.”

The legislation was written for American consumers, Weber said in a press release. Its purpose is to reduce a patchwork of state recycling and composting laws that only confuse people, he said, and make it hard for them to know which products are recyclable, compostable or destined for the landfill.

But it’s clear that California’s laws — such as Senate Bill 343, which requires that packaging meet certain recycling milestones in order to carry the chasing arrows recycling label — are the ones he and the industry have in mind.

“Packaging and labeling standards in the United States are increasingly influenced by state-level regulations, particularly those adopted in California,” Weber said in a statement. “Because of the size of California’s market, standards set by the state can have national implications for manufacturers, supply chains and consumers, even when companies operate primarily outside of California.”

It’s a departure from Weber’s usual stance on states’ rights, which he has supported in the past on topics such as marriage laws, abortion, border security and voting.

“We need to remember that the 13 Colonies and the 13 states created the federal government,” he said on Fox News in 2024, in an interview about the border. “The federal government did not create the states. … All rights go to the people in the state, the states and the people respectively.”

During the 2023-2024 campaign cycle, the oil and gas industry was Weber’s largest contributor, with more than $130,000 from companies such as Philips 66, the American Chemistry Council, Koch Inc. and Valero, according to OpenSecrets.org.

Weber did not respond to a request for comment. The bill has been referred to the House Energy and Commerce Committee.

Plastic and packaging companies and trade organizations such as Ameripen, Keurig, Dr Pepper, the Biodegradable Plastics Industry and the Plastics Industry Assn. have come out in support of the bill.

Other companies and trade groups that manufacture plastics that are banned in California — such as Dart, which produces polystyrene, and plastic bag manufacturers such as Amcor — support the bill. So do some who could potentially lose their recycling label because they’re not meeting California’s requirements. They include the Carton Council, which represents companies that make milk and other beverage containers.

“Plastic packaging is essential to modern life … yet companies and consumers are currently navigating a complex landscape of rules around recyclable, compostable, and reusable packaging claims,” Matt Seaholm, chief executive of the Plastics Industry Assn., said in a statement. The bill “would establish a clear national framework under the FTC, reducing uncertainty and supporting businesses operating across state lines.”

The law, if enacted, would require the Federal Trade Commission to work with third-party certifiers to determine the recyclability, compostability or reusability of a product or packaging material, and make the designation consistent across the country.

The law applies to all kinds of packaging, not just plastic.

Lauren Zuber, a spokeswoman for Ameripen — a packaging trade association — said in an email that the law doesn’t necessarily target California, but the Golden State has “created problematic labeling requirements” that “threaten to curtail recycling instead of encouraging it by confusing consumers.”

Ameripen helped draft the legislation.

Advocates focused on reducing waste say the bill is a free pass for the plastic industry to continue pushing plastic into the marketplace without considering where it ends up. They say the bill would gut consumer trust and make it harder for people to know whether the products they are dealing with are truly recyclable, compostable or reusable.

“California’s truth-in-advertising laws exist for a simple reason: People should be able to trust what companies tell them,” said Nick Lapis, director of advocacy for Californians Against Waste. “It’s not surprising that manufacturers of unrecyclable plastic want to weaken those rules, but it’s pretty astonishing that some members of Congress think their constituents want to be misled.”

If the bill were adopted, it would “punish the companies that have done the right thing by investing in real solutions.”

“At the end of the day, a product isn’t recyclable if it doesn’t get recycled, and it isn’t compostable if it doesn’t get composted. Deception is never in the public interest,” he said.

On Friday, California’s Atty. Gen. Rob Bonta announced settlements totaling $3.35 million with three major plastic bag producers for violating state law regarding deceptive marketing of non-recyclable bags. The settlement follows a similar one in October with five other plastic bag manufacturers.

Plastic debris and waste is a growing problem in California and across the world. Plastic bags clog streams and injure and kill marine mammals and wildlife. Plastic breaks down into microplastics, which have been found in just about every human tissue sampled, including from the brain, testicles and heart. They’ve also been discovered in air, sludge, dirt, dust and drinking water.

-

Sports2 days ago

Sports2 days agoMiami’s Carson Beck turns heads with stunning admission about attending classes as college athlete

-

Detroit, MI6 days ago

Detroit, MI6 days agoSchool Closings: List of closures across metro Detroit

-

Lifestyle6 days ago

Lifestyle6 days agoJulio Iglesias accused of sexual assault as Spanish prosecutors study the allegations

-

Education1 week ago

Education1 week agoVideo: Violence at a Minneapolis School Hours After ICE Shooting

-

Oklahoma1 week ago

Oklahoma1 week agoMissing 12-year-old Oklahoma boy found safe

-

Culture1 week ago

Culture1 week agoTry This Quiz on Myths and Stories That Inspired Recent Books

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoSan Antonio ends its abortion travel fund after new state law, legal action

-

Education1 week ago

Education1 week agoVideo: Lego Unveils New Smart Brick