Lifestyle

L.A. Crafted

(Textile sculpture of crafting materials and tools made by Los Angeles artist Mashanda Lazarus; photo by Robert Hanashiro / For The Times)

Los Angeles’ creative class extends far beyond Hollywood. In this series, we highlight local makers and artists, from woodworkers to ceramists, weavers to stained glass artists, who are forging their own path making innovative products in our city.

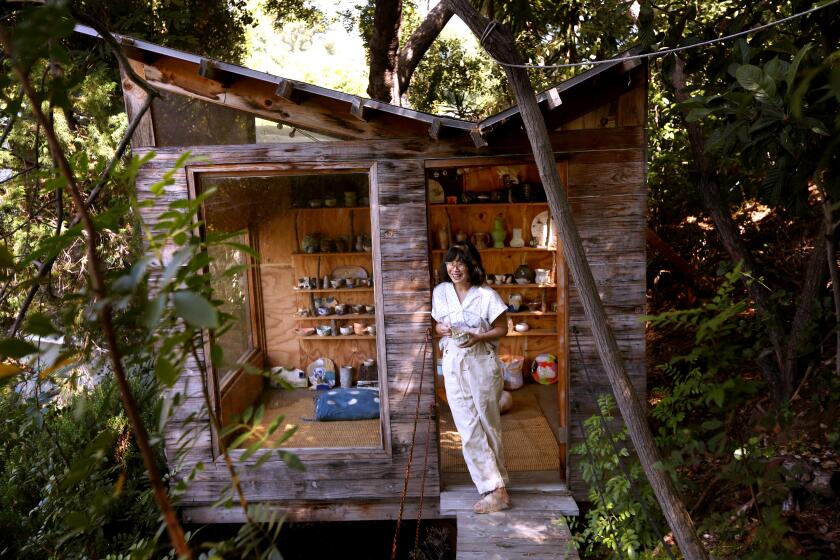

The home of ceramist Raina Lee includes a tree house featuring her pottery as well as a garage studio that houses her pottery wheel, kilns and her crackly volcanic glazes.

Los Angeles glassblower Cedric Mitchell relishes his role as a rulebreaker. “I wanted to break all the design rules similar to Ettore Sottsass,” he says, “and develop my own style.”

Vince Skelly, a Claremont designer, transforms raw timber into decorative and functional works of art. He starts with a chainsaw and transitions to other tools to add nuance.

Krysta Grasso’s vibrant crochet brand, Unlikely Fox, is dedicated to her late mother, who taught her to crochet when she was 5.

Daniel Dooreck’s fascination with motorcycles, flash tattoos and cowboys comes alive in the hand-thrown vessels he creates in his tiny Echo Park garage.

Julie Jackson’s use of reclaimed wood reinforces her commitment to creating sustainable home goods that tread lightly on the environment.

Soraya Yousefi’s art career started by accident, but she’s found her stride making whimsical bowls and cups in her Northridge home studio.

After managing grief, anxiety and depression, video game designer Ana Cho turned to pottery and woodworking to sustain her.

L.A. woodworker C.C. Boyce is reevaluating what happens when a person dies by turning ashes into planters.

Inspired by her career in automotive engineering, L.A. ceramist Becki Chernoff throws ceramic dinnerware that is clean-lined like the cars she loves.

Lifestyle

Meet the power couples of the 2026 Winter Games, from rivals to teammates

Oksana Masters and Aaron Pike at the Beijing 2022 Winter Paralympics. They bonded at a Para Nordic competition in 2013 over their love of coffee.

Michael Steele/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Michael Steele/Getty Images

Want more Olympics updates? Subscribe here to get our newsletter, Rachel Goes to the Games, delivered to your inbox for a behind-the-scenes look at the 2026 Milan Cortina Winter Olympics.

MILAN — Hundreds of incredible athletes are taking part in these Winter Games. And a number of them just happen to be dating — or engaged or married to — each other.

Some participate in the same sports, as teammates or even opponents, while others come from different athletic backgrounds.

Take U.S. Paralympians Oksana Masters and Aaron Pike, who both compete in several summer and winter sports. They first met at a Para Nordic competition in 2013, where they bonded over their love of coffee, before connecting on a deeper level at the 2014 Sochi Games.

“We had a really special moment where we kind of realized on a gondola that this is more than just a friend — like a hug that spoke a thousand words kind of thing,” Masters told NPR in October. “[I] realized, ‘Oh my gosh, this is not just something like a small attraction here.’”

Fast forward to 2022, and Pike proposed to Masters on a gondola in Wyoming. Masters has very publicly gone dress shopping — even bringing her two Paris 2024 gold medals with her — but they haven’t announced a wedding date yet. They said they were considering getting married after the Paralympics in Italy, while their families are already gathered together.

“In Italy would be a perfect way for our forever journey [to] start together, because of skiing in the mountains,” Masters said. “But, then, you need to ask him, too — more — because he’s doing nothing for the planning at all.”

NPR did ask Pike.

“I made a joke one time like: I proposed, now it’s your turn,” he said with a laugh. “And she will not let that go.”

Below are some of the Team USA winter power-couples to know, plus a few honorable mentions.

Hilary Knight and Brittany Bowe

At the socially-distanced Beijing Games in 2022, Hilary Knight asked Brittany Bowe if she wanted to go for a walk.

“That became our routine,” said Bowe. “We’d walk the Village after dinner and just talk. It was cool living in a bubble and not having outside distractions.”

Now they’re sharing another Olympics together.

It’s the fifth for Knight, the women’s hockey captain and all-time leading scorer for Team USA, and the fourth for Bowe, a two-time medalist in long-track speed skating. And this time, they’re not isolated in a bubble.

“It’s always nice to be able to support Hilary, and when we can see each other’s events,” Bowe said after attending Knight’s first match. “Her family was there, my whole family was there. It just brings additional energy to the atmosphere.”

Kaysha Love and Hunter Powell

Bobsledders Kaysha Love and Hunter Powell celebrate after Love won a race in Lake Placid, N.Y., in March 2025. The couple is now engaged.

Al Bello/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Al Bello/Getty Images

Bobsled athletes Kaysha Love and Hunter Powell met when they were track and field stars at their respective colleges. Love switched to bobsled and made the 2022 Olympics, then urged Powell to do the same.

“She convinced me to go to #SlideToGlory [a USA recruitment event,] which I was very resistant to, but she talked me into it, and I’m so thankful that she did,” Powell said from Cortina.

They got engaged in July 2025. Now, they’re Olympic teammates.

“It’s the coolest thing in the world,” Powell added. “I’m travelling the world for the first time in my life, chasing the dream, with the woman I love and my best friend. It doesn’t get cooler than that.”

Red Gerard and Hailey Langland

Snowboarders Red Gerard and Hailey Langland at an event in 2023 at Park City, Utah.

Joe Scarnici/Getty Images for JBL

hide caption

toggle caption

Joe Scarnici/Getty Images for JBL

Snowboarders Red Gerard and Hailey Langland have known each other since they were 12, and have been in a relationship for the past eight years.

They both competed at the Olympics in Pyeongchang in 2018 — where Gerard won gold — and 2022 in Beijing. He is competing again this year. She’s sidelined by an ACL injury, but staying with him and his parents in Italy.

Madison Chock and Evan Bates

Evan Bates took Madison Chock on a date on her 16th birthday, though it didn’t immediately lead to anything.

Several years later, in 2011, they partnered up in ice dance. Six years later, Bates confessed his feelings.

“Well, I pretty much told Maddie that I loved her,” Bates told NBC in 2018. “Last year I told (her) how I really felt and that changed things a lot.”

The two got engaged in 2022 and married in the summer of 2024 in Hawaii, where Chock’s parents are from. Bates told NPR in October that while “the skating career is short and finite, the relationship is much, much longer.”

“We love what we do, but we also really love each other,” Chock added. “And we’re able to take this passion and use it to foster our connection as a couple. And I think from that we’ve grown a lot through our sport, and that’s been such a great teacher for us.”

They’re not the only ice dance power couple on Team USA: Emilea Zingas and Vadym Kolesnik have been partners on and off the ice since 2022.

Other couples to know

Marie-Philip Poulin, right, and Laura Stacey of Team Canada celebrate after winning the hockey gold medal match against Team United States.

Elsa/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Elsa/Getty Images

- Hockey greats Marie-Philip Poulin and Laura Stacey play together for the Montreal Victoire, and for Team Canada (of which Poulin is the captain). They’ve been together since 2017 and married since 2024.

- Kim Meylemans and Nicole Silveira are both skeleton racers, representing opposing teams (Belgium and Brazil). They’re also newlyweds, having married less than a year ago after sparking up a relationship during the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Anna Kjellbin and Ronja Savolainen met while playing together in the Swedish pro women’s hockey league, before getting signed to separate teams in Canada. The now-fiances are playing for separate teams at the Olympics, too: Sweden and Finland.

- There are three married couples in this year’s 10-team mixed doubles curling field:

- Italian ice dancers Charlene Guignard and Marco Fabbri have been together since 2009, with the on-ice PDA to prove it.

- Jocelyn Peterman and Brett Gallant of Canada, Switzerland’s Yannick Schwaller and Briar Schwaller-Hürlimann, and Kristin Skaslien and Magnus Nedregotten of Norway.

Lifestyle

How to have the best Sunday in L.A., according to Sheila E.

The way Sheila E. remembers it, she received her first call about a gig as a working Los Angeles musician as she was busy unpacking the moving truck with which she’d just moved to L.A.

“‘Can you come do a session?’ — that type of thing,” the Oakland native recalls with a laugh. “It was pretty awesome.”

In Sunday Funday, L.A. people give us a play-by-play of their ideal Sunday around town. Find ideas and inspiration on where to go, what to eat and how to enjoy life on the weekends.

This was 1980 or ’81, she reckons, just after she’d come off the road playing percussion for the jazz star George Duke; by 1984, she’d become a star herself with the pop hit “The Glamorous Life,” which she cut with her mentor Prince and which went to No. 7 on Billboard’s Hot 100.

Over the decades that followed, Sheila E. went on to record or perform with everyone from Ringo Starr to Beyoncé. Yet her latest projects look back to her earliest days playing Latin jazz with her father, fellow percussionist Pete Escovedo: “Bailar” is a salsa album with guest vocal spots by the likes of Rubén Blades and Gloria Estefan, while an accompanying instrumental disc features appearances by players such as bassist Marcus Miller and trumpeter Chris Botti.

Sheila E. will tour Europe in April. Here, she runs down her routine for a welcome day off at home in L.A.

10 a.m.: Parents in the pews

I would get up around 7:30 or 8, and the first thing I’ll do is go to church. My church is called Believe L.A., and it’s in Calabasas. My pastor is Aaron Lindsey, who’s an incredible gospel producer who’s won many Grammys. The band is always on point, and it feeds my soul — it’s what I need as part of my food. You just walk out so happy. I mean, I walk in happy most of the time. But you walk out filled with love and peace. It’s a joyful time, especially when I get to bring my parents with me. Still having them around is a huge blessing. They just celebrated their 69th anniversary. That’s really rare.

Noon: No juice required

After church we’ll go to brunch at Leo & Lily in Woodland Hills. Sometimes I’ll order the breakfast, which is two eggs and turkey bacon and potatoes. But sometimes that’s a little bit too heavy, so I’ll get the orzo salad, which is really good. I might have an espresso, or I might have a glass of Champagne. I don’t like mimosas — just give it to me straight.

1:30 p.m.: Retail therapy

My parents love driving down Ventura Boulevard. We’ll stop at some places and go window shopping, or maybe we’ll go to the Topanga Westfield mall. And when we finish at the mall, I have to go to Costco. The Costco run is really just for my dog — I have to get all her food. I get turkey and vegetables, and I cook all that and pre-make her meals for two weeks so I don’t have to deal with it. I can just open it, warm it up and feed her. She’s a mixed pit rescue, and her name is Emma. I got her when she was 5 months old in Oakland while we were performing, and now she’s 12. She’s a sweetheart.

4 p.m.: Family secret

We’re sports fans, so if it’s football season, we have to hurry up and get back to my house for the game. We’re a 49ers family. I would say the Raiders because we’re from Oakland, but we’ve always been 49ers fans. I mean, when it’s time to root for the Raiders, we do. We don’t hate like the Raiders hate on us. I’ll cook food depending on who all’s coming over — my nephews and various friends and so on. I grill a lot, so I’ll do steaks or lamb chops or chicken wings. My mom loves making potato salad. I can’t tell you the recipe — it’s a secret. It’s actually her mother’s potato salad, and they’re Creoles. Those Creoles don’t mess around with their potato salad.

8:30 p.m.: Games after the game

I never tell anyone to leave. Sometimes people spend the night — it’s an open house. If we’re not too tired, we’ll start playing board games or card games. Don’t get us started on poker.

11:30 p.m.: Steam time

Before bed I’ll get into the sauna just to relax and do a little sweating. Then I go take a shower with jazz or spa music playing. Sometimes I’ll do a little stretching before I get in the bed. I usually don’t read before I go to sleep. My go-to is HGTV — I set it for an hour and a half, and I’m out.

Lifestyle

Consider This from NPR

How the Epstein files are upending U.K. politics

-

Alabama1 week ago

Alabama1 week agoGeneva’s Kiera Howell, 16, auditions for ‘American Idol’ season 24

-

Illinois1 week ago

Illinois1 week ago2026 IHSA Illinois Wrestling State Finals Schedule And Brackets – FloWrestling

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoApple might let you use ChatGPT from CarPlay

-

Culture1 week ago

Culture1 week agoTry This Quiz on Passionate Lines From Popular Literature

-

Science1 week ago

Science1 week agoTorrance residents call for the ban of ‘flesh-eating’ chemical used at refinery

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoVirginia Dems take tax hikes into overtime, target fantasy football leagues

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoWest Virginia worked with ICE — 650 arrests later, officials say Minnesota-style ‘chaos’ is a choice

-

Movie Reviews1 week ago

Movie Reviews1 week agoAshakal Aayiram Movie Review: Jayaram’s performance carries an otherwise uneven family drama