Lifestyle

'It's totally different': Younger tattoo artists are ditching the machine

Abby Ingwersen, a guest artist at Nice Try Tattoo, works on a client using the stick and poke method.

Mengwen Cao for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Mengwen Cao for NPR

For purveyors of an artform that’s famously permanent, tattoo artists sure like to switch things up.

In studios and shops around the world, younger artists are challenging the traditional ways of running a business and poking ink into skin.

From independent collectives to a revival of the so-called “stick and poke” tattoo, a new generation is leaving its mark.

A new studio structure

In a typical walk-in tattoo shop, there is an owner, some contracted artists and maybe an apprentice. The artists pay a percentage of their earnings to the owner in return for expertise, a place to work and a storefront to attract clients.

But some artists are forging ahead with a new, non-hierarchical vision: the independent studio, where the idea is to cut out the middle-man.

That’s where you will find Ella Sklaw, one of the five artists who works out of Nice Try Tattoo — a collaboratively-owned and operated tattoo studio they started three years ago with a friend in Brooklyn, New York.

The members of Nice Try Tattoo, which includes (clockwise from top left) Cierson Zambo, Sydney Kleinrock, Ella Sklaw, Sara Sremac and Lu Walstad.

Mengwen Cao for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Mengwen Cao for NPR

Ella Sklaw talks through the process with their client, Maddie Dennis-Yates.

Mengwen Cao for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Mengwen Cao for NPR

From the outside, Nice Try Tattoo is an unassuming warehouse. But once you enter, you’re met with comfy couches, walls plastered with thank you notes, and a wooden dining table in the back.

“We visually decorate the entire shop together,” Sklaw says. “We try to keep it super warm and super inviting. I think we really go for this idea that you should have stuff to look at while you’re getting a tattoo, because it hurts.”

For Maddie Dennis-Yates, one of Sklaw’s clients on a recent summer day, those touches are appreciated.

“There’s been a real shift in the vibe of tattoo studios lately,” Dennis-Yates says. “Even just having it in a building like this, it’s got this certain coziness to it. Like, you have to go find it somewhere, you can’t just stumble in off the street.”

For an array of reasons, the pandemic contributed to the rise of independent studios — some artists took up the skill during lockdown, while some clients found extra money or the confidence to get inked. And while there isn’t complete data on the number of independent studios versus traditional shops, the industry as a whole grew a steady 2.5% a year from 2018-23, according to research from IBISWorld.

The move towards independent work models is a symptom of something larger, especially for artists and creatives who have been the most historically exploited, according to Trebor Scholz, a New School professor who researches cooperative entrepreneurship.

“We have seen the increase during the pandemic, but this is something that is part of a much longer shift in the way work has performed over the past 50 years really, and these kind of non-standard work arrangements,” he said. “I don’t think the clock will be turned back on them.”

A “stick and poke” revival

Along with a shift in the business model there are also evolving styles and tastes — both from customers and artists.

Some artists at Nice Try Tattoo have left the machine behind and rely on a singular needle to etch their designs. It’s a method often called “stick and poke” or “hand poke.”

Nicole Monde works out of a private studio in Brooklyn.

Mengwen Cao for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Mengwen Cao for NPR

“I just take the needle and I just put it in my hand and then I just poke the design dot by dot,” says Nicole Monde, a hand poke artist who shares a private studio space in Brooklyn. “It’s very similar to machine in that it’s going the same depth, I’m using the same ink, same supplies, same needles and everything, but I’m just taking the machine out of it.”

Hand poke tattoos can conjure up images of college dorm rooms or DIY mishaps, and Monde acknowledges it’s not always seen as legitimate.

Monde puts together a tattoo design.

Mengwen Cao for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Mengwen Cao for NPR

“I think a lot of people don’t see it as a valid form of tattooing because the industry standard for so long has been using a machine. But I like to point out the fact that before electricity existed, this is how all tattoos were being done,” she says.

Some clients, like E Barnick, prefer hand poke tattoos for the overall experience.

“It’s totally different,” Barnick says. “I mean, it doesn’t hurt nearly as much and it’s also just a lot more intimate to have somebody hand poking.”

Still, some artists make the case that there are benefits to the traditional shop model that are lost when artists work out of independent studios and trade in different approaches.

“They’re missing out on the grander scale of experience and I think it’s harder to advance as an artist. I think you need that interaction with the average daily wacko wandering in off the street,” says Mehai Bakaty, who owned Fineline Tattoo in Manhattan until it was forced to close due to rising costs and the pandemic lockdowns.

Still, Bakaty now works from an independent studio as well, and says it takes him back to the 1990s when New York tattoo shops used to all operate under the radar because their operations were illegal and there were concerns about AIDS transmission.

“Sort of underground, clandestine, appointment-only, word of mouth, no advertising, no storefronts,” he says.

It’s not lost on Sklaw, from Nice Try Tattoo, that their collective studio model has come full circle back to these same ideas: word of mouth. No storefronts. No walk-ins.

Sklaw works on a client.

Mengwen Cao for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Mengwen Cao for NPR

Artist Sara Sremac show her client E Barnick their new tattoo.

Mengwen Cao for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Mengwen Cao for NPR

“We kind of exist in the legacy of that alternative space,” Sklaw says.

These days, whether clients choose a machine or hand-poked tattoo, at an indie studio or a shop, the goal is the same: distinctive, meaningful, permanent art.

“Tattoos, I mean, cross-culturally, were always something to be extremely proud of,” says Lars Krutak, a tattoo anthropologist. “Because we’re talking primarily these … identify you as a member of a community.”

So when clients leave Nice Try Tattoo or a traditional shop, they aren’t just coming home with a new tattoo. The marking is a symbol of a community much larger than a singular artist or a singular needle.

Lifestyle

Pageant Winner Kayleigh Bush Rips Miss America After Being Stripped of Crown

Pageant Winner Kayleigh Bush

Miss America Went Down The Toilet

Published

TMZ.com

Beauty pageant winner Kayleigh Bush used to admire Miss America, but now she’s ripping the organization for being unable to define what a woman is … along with disagreements over trans women, which led to her being stripped of her crown.

We got Kayleigh on Capitol Hill and our photog asked her about her beef with Miss America … and she explained how some controversial language in her Miss America contract led to a falling out.

Kayleigh was crowned Miss North Florida in September 2024, but two months later, she was stripped of her crown … because she refused to sign a contract with Miss America that she says went against her beliefs … namely, that women also include biological males who undergo transgender reassignment surgery.

She says the contract would have opened the door for her to compete against transgender women … which she wasn’t on board with … and when she didn’t sign on the dotted line, Miss America stripped her crown.

Kayleigh’s got a new crown and sash, though … proudly showing off her “Miss She Leads America” distinction and touting her celebrity support.

It’s an interesting conversation … and the whole saga has tarnished Miss America in Kayleigh’s eyes.

Lifestyle

A daughter reexamines her own family story in ‘The Mixed Marriage Project’

Dorothy Roberts (left) is the George A. Weiss university professor of law & sociology at the University of Pennsylvania. Her parents, Robert and Iris, married in the 1950s.

Cris Crisman/Simon & Schuster; Dorothy Roberts

hide caption

toggle caption

Cris Crisman/Simon & Schuster; Dorothy Roberts

Almost a decade after her father’s death, legal scholar Dorothy Roberts still had 25 boxes of his research that she had yet to sort through. When she moved from Chicago to Philadelphia, she brought the boxes — and finally opened them.

Roberts’ father, Robert Roberts, was a white anthropologist who spent his career at Roosevelt University in Chicago. The boxes contained transcripts of nearly 500 interviews he had conducted with interracial couples across the city, including interviews with couples who were married in the late 1800s, all the way to couples who are married in the 1960s.

“They were absolutely fascinating,” Roberts says of the transcripts. “I learned so much about the racial caste system in Chicago, the Color Line, the Black Belt.”

Initially, Roberts saw the project as a chance to finish her father’s work, but as she examined the documents, she learned more about her own family — including the fact that her mother, Iris, a Black Jamaican immigrant, had assisted in her husband’s research.

“When I got to the 1950s interviews, I discovered that my mother was conducting all the interviews of the wives, while my father conducted the interviews for the husbands,” Roberts says. “Finding out that my mother was involved … created curiosity I had about my family, about their marriage, and then I began to think about how it related to me and my identity as a Black girl with a white father.”

In her new book, The Mixed Marriage Project: A Memoir of Love, Race, and Family, Roberts dives into her parents’ research and her surprise at learning that she was included as participant number 224 in the files. She also shares her own thoughts on interracial relationships.

“My father thought that interracial intimacy was the instrument to end racism, and I think it’s really flipped the other way,” she says. “We end racism when we will see the possibility of truly being able to love each other as equal human beings.”

Interview highlights

The Mixed Marriage Project, by Dorothy Roberts

Simon & Schuster

hide caption

toggle caption

Simon & Schuster

On white European immigrant women marrying Black men in the early 20th century

These were immigrant women coming from Europe who had no familiarity at all with the racial caste system in Chicago. … So when they marry Black men, in fact, they thought that marrying an American citizen would help them assimilate into American culture. So they had no idea … that if they married a Black man, it would do the opposite to them. They would be lower in their status than they were as white immigrants. And so many of them would say, “I found out that I had to live in a colored neighborhood. I had to leave my white neighbors. I had left my family in order to marry this Black man and move into the Black Belt. I now couldn’t even tell my employer my address, because if they found out my address, they’d know I must be living with a Black man.” Why else would a white woman be living in the Black Belt?

They were afraid they would lose their jobs, and many reported that they were fired as a result of their employer finding out that they were married to a Black man. They were met with stares when they got on the streetcar. Many said that if they were going on a streetcar in Chicago, they would go on separately and pretend they didn’t know each other so that no one would know that they were married.

On the difference between her father’s and mother’s notes in the project

My father, much to my horror, was very anthropological in terms of the physical traits of the people he interviewed. He wrote about the “Negroid traits” and whether the child had any trace of “Negroid blood” and that sort of thing. Again, remembering he was doing this in the 1930s.

My mother was much more interested in the personality traits of the people she interviewed and what their furniture looked like and her own emotions. And there’s just so many delightful things. The way in which she interacts with the children when she’s interviewing the wives — there’s a lot more attention to what the children are doing. I can’t remember a single interview where my father really describes the children’s behavior. He describes their physical appearance, but my mother would describe their behavior and their interaction with the mother. All of that is part of the interview and her notes, and she writes it almost like a screenplay. It’s really, really wonderful to read.

On the fetishization of interracial intimacy and biracial children

There was this visceral feeling I felt whenever a Black man, a Black husband, would talk about his preference for being with white women. These ideas that interracial intimacy has an extra excitement to it. It has an extra titillation to it — that kind of idea came up in many of the interviews — and I just have a very visceral revulsion at that kind idea, a sort of a fetishization of interracial intimacy and also of biracial children. The idea that whitening children makes them more attractive or makes them more intelligent or more appealing, more lovable. And whenever that came up, I just, sometimes I had to just throw the interview down because I couldn’t stand that kind of thinking.

On her decision to identify as Black in college and hide her dad’s whiteness

I now regret that I hid the fact that my father was white, that I denied him that part of my identity or denied the reality that he was part of my identity. … I think I very wrongly believed that if they knew my father was white, I somehow wouldn’t be as much an integral part of these groups, that they might feel differently about me. …

I realized by the end of working on the memoir that I am a Black woman with a white father [and] I should not deny all that my father contributed to my identity. I would not be the Black woman I am today, I probably would not have done the work against racism and against the demeaning of Black women, I would have not done the [work] to uplift Black women if it weren’t for my father and all that he taught me. And I need to appreciate and acknowledge all that my father contributed to the Black woman I am today.

On what this project has taught her about love and race

It showed me more powerfully than anything I’d ever read before how the invention of race, the lie that human beings are naturally divided into races, can erase the very ties of family. … In my own case, my father’s younger brother, my uncle Edward, disowned him when he married my mother. And even though he lived in the Chicago area and I had cousins who lived there, I never met them because of this rift, this divide between my father and his brother.

Working on the memoir also made me realize that all the work I’ve been doing throughout my career was trying to answer this question of, what does it take to love across the chasm of race? That’s what these couples are telling us, even the ones who were still racist. … They’re telling us what it takes to challenge and dismantle structural racism in America. And so, to me, these interviews persuaded me even more that we can believe in our common humanity. We can overcome the seemingly unbreakable, unshakable shackles of structural racism. But it can’t be simply by pretending that the sentiment of love or even loving someone across the racial lines will do it. We have to see the work that it’s going to take to do that.

Anna Bauman and Nico Gonzalez Wisler produced and edited this interview for broadcast. Bridget Bentz, Molly Seavy-Nesper and Meghan Sullivan adapted it for the web.

Lifestyle

What playing a 7-hour video game with strangers in L.A. taught me about the resistance

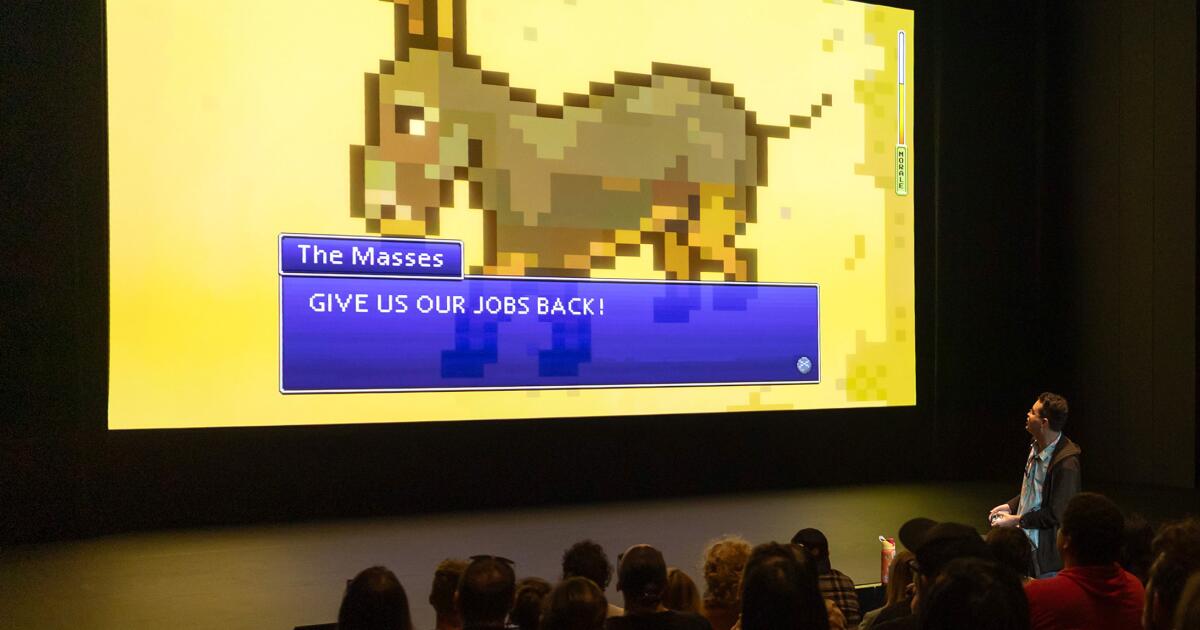

The donkeys are pissed off. Put upon, out of work and victims of decades-long systemic abuse, it’s time, they have decided, to protest.

The donkeys, metaphorically, are us.

At least that’s the premise of “asses.masses,” a video game played by and for a live audience. It’s theater for the post-Twitch age, performance art for those weaned on “The Legend of Zelda” or “Pokémon.” Most important, it’s entertainment as political dissent for these divisive times. Though the project dates to 2018, it’s hard not to draft 2026 onto its narrative. Whether it’s unjust incarceration, mass layoffs or topics centered around tech’s automation of jobs, “asses.masses,” despite generally lasting more than seven hours — yes, seven-plus hours — is a work of urgency.

The audience cheers various decisions made during the playing of “asses.masses” at UCLA Nimoy Theater.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

And for the audience at the Saturday showing at the UCLA Nimoy Theater, it felt like a call to arms. Citizens executed in the street for exercising their right to free speech? That’s in here. Run-ins with authorities that recall images seen in multiple American cities over the past few months? Also in here, albeit in a retro, pixel art style that may bring to mind the “Final Fantasy” series from its Super Nintendo days.

In a city that’s been ravaged by fires, ICE raids and a series of entertainment industry layoffs, the sold-out crowd of nearly 300 was riled up. Chants of “ass power!” — the donkey’s protest slogan — were heard throughout the day as attendees politely gathered near a single video game controller on a dais to play the game, becoming not just the avatar for the donkeys but a momentary leader for the collective. Cheers would erupt when a young donkey reached the conclusion that “I kinda think the system is rigged against everyone.” And when technological advances, clearly a stand-in for artificial intelligence, were described as “evil, soulless, job-taking, child-killing machines,” there were knowing claps, as if no exaggeration was stated.

“Our theater is supposed to be a rehearsal for life,” says Patrick Blenkarn, who co-created the game with Milton Lim, interdisciplinary artists from Canada who often work with interactive media.

“We grew up in a radical political tradition of theater,” says Patrick Blenkarn, right, who co-created “asses.masses” with Milton Lim.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

“We grew up in a radical political tradition of theater, where this is where we can rehearse emotional experience — catharsis,” Blenkarn says. “That is what art is supposed to be doing. We have been very interested in the idea that if we come together, what are we going to do and how are we going to do it? What we are seeing in your country, and other countries, is the question of how are we going to change our behavior, and will the people who currently have the controller listen? And if they don’t, what do we do?”

Video games are inherently theatrical. Even if one is playing solo on the couch, a video game is a dialogue, a performance between a player and unseen designers. Blenkarn and Lim also spoke in an interview prior to the show of wanting to re-create the sensation of gathering around a television and passing a controller back and forth among family or friends while offering commentary on someone’s play style. Only at scale. And while I thought “asses.masses” could work, too, as a solitary experience at home, its themes of collective action and reaching a group consensus, often through boos or shouts of encouragement, made it particularly well-suited for a performance.

The UCLA Nimoy Theater played host to “asses.masses” this weekend.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

Beginning at 1 p.m. and ending shortly after 8 p.m., coincidentally, says Blenkarn, the length or so of a working day, not everyone made it to the “asses.masses” conclusion. About a quarter of the audience — a crowd that was clearly familiar with the multiple video game style represented in “asses.masses” — couldn’t stand the endurance test. But in a time of binge-watching, I didn’t find the length prohibitive. There were multiple intermissions, but those became part of the show as well, as there was no set time limit. Blenkarn and Lim were asking the audience, via a prompt on the screen, to jointly agree upon a length, emphasizing, once again, the importance of collective cooperation.

And “asses.masses” holds interest because it, in part, embraces the animated absurdity and inherent experimentation of the medium. While often in a retro pixel art style, at times the game shifted into a more modern open-world look. And the story veers down multiple paths and side-quests — some requiring wild coordination such as a rhythm game meant to simulate donkey sex, and others more tense, such as “Metal Gear”-like sneaking, complete with the donkeys hiding in cardboard boxes.

Audiences vote, often by cheering or booing, on choices in “asses.masses.”

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

The way “asses.masses” shifted tones and tenor recalled a game such as “Kentucky Route Zero,” another serialized and alternately realistic and fanciful game with political overtones. Other times, such as the surreal world of the donkey afterlife, I thought of the colorfully unpredictable universe of the music-focused game “The Artful Escape,” a quest for personal identity and self-actualization. The donkeys in “asses.masses” are an ensemble, often trying to steer the audience in different directions. As much as some push for a protest as a way for communal healing and progressive action, others take a cynical outlook, viewing that path as “intellectually compromised” by a “commitment to past ideals.”

The goal, says Lim, is to create a sort of game within a game — one that’s being played with a controller and one of debate among a crowd. “It’s not about having a billion endings,” Lim says. “We understand it’s a theater show, and we as writers have objectives for what we want it to go towards. But the decisions people make in the room really matter. The game is half in the room and half on the screen.”

The audience, for instance, can play a role in keeping certain donkeys alive. Or what jobs a group of renegade donkeys may choose. Our audience voted for the donkeys to enter the circus, at least until they were deemed obsolete and sent to detention centers, which felt uncomfortably of the moment. Such topicality is what drew Edgar Miramontes, leader of CAP UCLA, to the show, despite his admittance to being largely unfamiliar with the world of video games.

“It doesn’t shy away from the nuances of when organizing happens and what we’re seeing in our world right now,” Miramontes says. “There are instances in which a donkey may die because, in organizing to achieve their goals, these things happen. We have seen this in our Civil Rights Movement and other movements and the current movement that’s happening right now around ICE.”

The Nimoy event, part of UCLA’s current Center for the Art of Performance season, was the 50th time “asses.masses” had been performed. The show will continue to tour, with a performance in Boston set for this upcoming weekend and it will reach Chicago later this year. Our donkeys on Saturday didn’t solve all the world’s inequalities, but they did live full lives, attending raves, engaging in casual sex and even playing video games.

A player celebrates during “asses.masses,” live action theatrical video game.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

The show is an argument that progress isn’t always linear, but community is constant. As one of the donkeys says at one point, “If you aren’t doing something that brings you joy, do something different.”

“In case anyone is like, ‘I don’t want to be lectured at,’ or I don’t want to do all this work, it feels like you’re just having fun with friends,” Lim says. “Maybe revolution doesn’t always look like just this. Maybe it’s also this.”

And like many a video game, maybe it’s a chance to live out some fantasies. “We do beat up riot cops in the game,” Blenkarn says, “in case anyone is hoping for that opportunity.”

-

Politics6 days ago

Politics6 days agoWhite House says murder rate plummeted to lowest level since 1900 under Trump administration

-

Indiana1 week ago

Indiana1 week ago13-year-old rider dies following incident at northwest Indiana BMX park

-

Indiana1 week ago

Indiana1 week ago13-year-old boy dies in BMX accident, officials, Steel Wheels BMX says

-

Alabama4 days ago

Alabama4 days agoGeneva’s Kiera Howell, 16, auditions for ‘American Idol’ season 24

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoTrump unveils new rendering of sprawling White House ballroom project

-

San Francisco, CA7 days ago

San Francisco, CA7 days agoExclusive | Super Bowl 2026: Guide to the hottest events, concerts and parties happening in San Francisco

-

Culture1 week ago

Culture1 week agoTry This Quiz on Mysteries Set in American Small Towns

-

Massachusetts1 week ago

Massachusetts1 week agoTV star fisherman’s tragic final call with pal hours before vessel carrying his entire crew sinks off Massachusetts coast