Science

What is Alaskapox? The disease has claimed its first fatality

Public health officials in Alaska have disclosed the first known human death from Alaskapox, a virus typically found in small mammals.

No human-to-human transmission of Alaskapox has been detected so far, and there have been no known cases outside the state for which the virus is named. California health officials confirmed there’ve been no reports of the virus in the state.

The first person known to die from the virus was an elderly man from Alaska’s Kenai Peninsula who was undergoing cancer treatment, state health officials said in a bulletin issued late last week.

The man’s symptoms began in mid-September with a painful red lesion near his shoulder that failed to respond to antibiotic treatment. By the time he was hospitalized in November, he was complaining of a burning pain that made it difficult to move his arm. Doctors noted four additional sores on other parts of his body, and sent swabs of the lesions to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for testing.

The man was taking medications to treat his cancer, and those drugs hobbled his immune system. Despite some positive response to antiviral treatment, his health declined rapidly in the hospital and he died in January.

The man was only the seventh known person to have become infected with the virus since it was first detected in humans in 2015, according to Alaska’s Department of Public Health. He was also the first person to have become ill enough to require hospitalization.

“The patient’s immunocompromised status likely contributed to illness severity,” state health officials said in a statement.

All previous patients complained of swollen lymph nodes and muscle aches that cleared up in a few weeks. The virus also causes one or more red, uncomfortable skin lesions, which several previous patients mistook for spider or insect bites.

Testing in 2020 and 2021 found the virus in several small mammal species in Alaska’s Fairbanks area, particularly shrews and red-backed voles. The man who died in January was the first person outside of the Fairbanks area to have been diagnosed with the virus, a sign that the virus has spread to mammals outside that region, health officials said.

The man lived alone in a forested region and had no known travel or contact with any potentially infected people.

He did care for a stray cat prone to both hunting small mammals and scratching its human caretaker, state officials noted. The cat had clawed the man on the shoulder a month before his symptoms began, close to the site where his first lesion was found. However, officials noted that they couldn’t be sure that was how the man acquired the virus.

“Wild animals can carry germs that can spread to people through direct or indirect contact and make people sick,” a spokesperson for the California Department of Public Health said in an email. “Even if an animal looks healthy, it can still spread germs that can cause disease. Do not touch or approach wild animals or any animals that you do not know.”

Alaskapox is an orthopoxvirus, the genus of viruses that includes smallpox and Mpox, formerly known as monkeypox.

Though no cases of human-to-human transmission of Alaskapox have been reported, Alaska health officials noted that other orthopoxviruses can spread via close contact with an infected person’s lesions. This is how health officials believe Mpox spread during the brief outbreak of 2022 in which a virus previously found in western and central Africa suddenly took off in Europe and the U.S.

Anyone with suspicious lesions who believes they could have the virus should cover the sore with a bandage until they can see a doctor and avoid sharing clothes or bedding with anyone else, Alaska’s Division of Public Health said.

Science

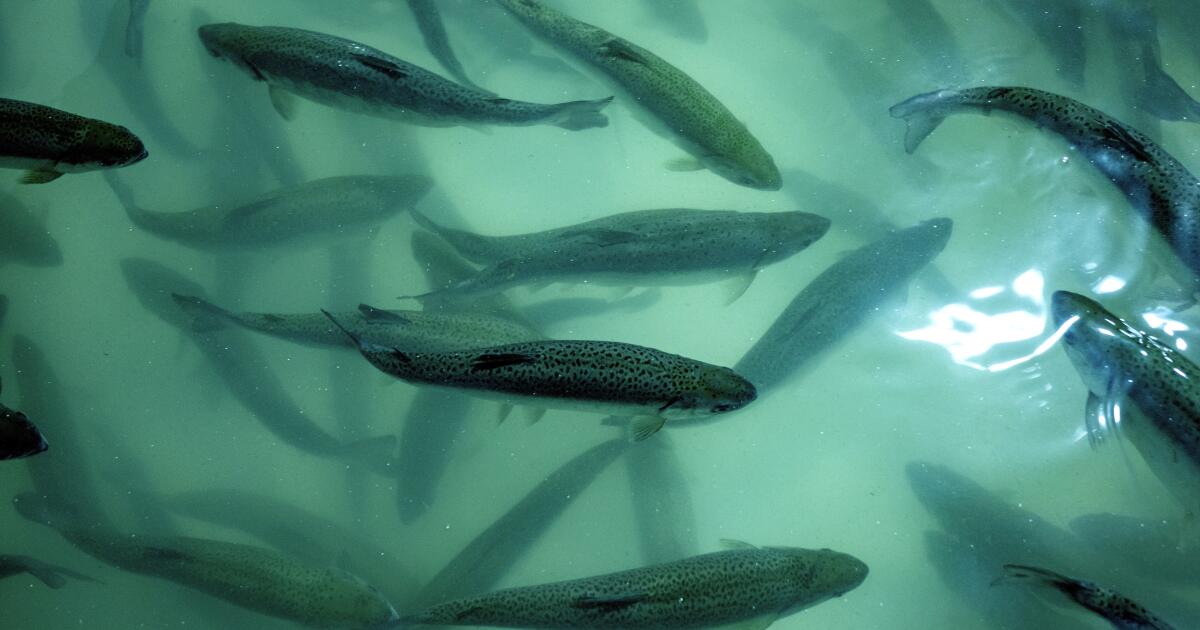

Contributor: Factory farming of fish is brewing pathogens

The federal government recently released new dietary guidelines aimed at “ending the war on protein” and steering Americans toward “real foods” — those with few ingredients and no additives. Seafood plays a starring role. But the fish that health advocates envision appearing on our plates probably won’t be caught in the crystal blue waters we’d like to imagine.

Over the past few decades, the seafood industry has completely revolutionized how it feeds the world. As many wild fish populations have plummeted, hunted to oblivion by commercial fleets, fish farming has become all the rage, and captive-breeding facilities have continually expanded to satiate humanity’s ravenous appetite. Today, the aquaculture sector is a $300-billion juggernaut, accounting for nearly 60% of aquatic animal products used for direct human consumption.

Proponents of aquaculture argue that it helps feed a growing human population, reduces pressure on wild fish populations, lowers costs for consumers and creates new jobs on land. Much of that may be correct. But there is a hidden crisis brewing beneath the surface: Many aquaculture facilities are breeding grounds for pathogens. They’re also a blind spot for public health authorities.

On dry land, factory farming of cows, pigs and chickens is widely reviled, and for good reason: The unsanitary and inhumane conditions inside these facilities contribute to outbreaks of disease, including some that can leap from animals to humans. In many countries, aquaculture facilities aren’t all that different. Most are situated in marine and coastal areas, where fish can be exposed to a sinister brew of human sewage, industrial waste and agricultural runoff. Fish are kept in close quarters — imagine hundreds of adult salmon stuffed into a backyard swimming pool — and inbreeding compromises immune strength. Thus, when one fish invariably falls ill, pathogens spread far and wide throughout the brood — and potentially to people.

Right now, there are only a handful of known pathogens — mostly bacteria, rather than viruses — that can jump from aquatic species to humans. Every year, these pathogens contribute to the 260,000 illnesses in the United States from contaminated fish; fortunately, these fish-borne illnesses aren’t particularly transmissible between people. It’s far more likely that the next pandemic will come from a bat or chicken than a rainbow trout. But that doesn’t put me at ease. The ocean is a vast, poorly understood and largely unmonitored reservoir of microbial species, most of which remain unknown to science. In the last 15 years, infectious diseases — including ones that we’ve known about for decades such as Ebola and Zika — have routinely caught humanity by surprise. We shouldn’t write off the risks of marine microbes too quickly.

My most immediate concern, the one that really makes me sweat, is the emergence of drug-resistant bacteria among farmed fish. Aquaculturists are well aware that their fish often live in a festering cesspool, and so many growers will mix antibiotics — including ones that the World Health Organization considers medically important for people — into fish feed, or dump them straight into water, to avoid the consequences of crowded conditions and prevent rampant illness. It would be more appropriate to use antibiotics in animals only when they are sick.

Because of this overuse for prevention purposes, more antibiotics are used in seafood raised by aquaculture than are used in humans or for other farmed animals per kilogram. Many of these molecules will end up settling in the water or nearby sediment, where they can linger for weeks. In turn, the 1 million individual bacteria found in every drop of seawater will be put to the evolutionary test, and the most antibiotic-resistant will endure.

Numerous researchers have found that drug-resistant strains of bacteria are alarmingly common in the water surrounding aquaculture facilities. In one study, evidence of antibiotic resistance was found in over 80% of species of bacteria isolated from shrimp sold in multiple countries by multiple brands.

Many drug-resistant strains in aquatic animals won’t be capable of infecting humans, but their genes still pose a threat through a process known as horizontal transfer. Bacteria are genetic hoarders. They collect DNA from their environment and store it away in their own genome. Sometimes, they’ll participate in swap meets, trading genes with other bacteria to expand their collections. Beginning in 1991, for example, a wave of cholera infected nearly a million people across Latin America, exacerbated by a strain that may have picked up drug-resistant adaptations while circulating through shrimp farms in Ecuador.

Today, drug-resistant bacteria kill over a million people every year, more than HIV/AIDS. I’ve seen this with my own eyes as a practicing tuberculosis doctor. I am deeply fearful of a future in which the global supply of fish — a major protein source for billions of people — also becomes a source of untreatable salmonella, campylobacter and vibrio. We need safer seafood, and the solutions are already at our fingertips.

Governments need to lead by cracking down on indiscriminate antibiotic use. It is estimated that 70% of all antibiotics used globally are given to farm animals, and usage could increase by nearly 30% over the next 15 years. Regulation to promote prudent use of antibiotics in animals, however, has proven effective in Europe, and sales of veterinary antibiotics decreased by more than 50% across 25 European countries from 2011 to 2022. In the United States, the use of medically important antibiotics in food animals — including aquatic ones — is already tightly regulated. Most seafood eaten in the U.S., however, is imported and therefore beyond the reach of these rules. Indeed, antibiotic-resistance genes have already been identified in seafood imported into the United States. Addressing this threat should be an area of shared interest between traditional public health voices and the “Make America Healthy Again” movement, which has expressed serious concerns about the health effects of toxins.

Public health institutions also need to build stronger surveillance infrastructure — for both disease and antibiotic use — in potential hotspots. Surveillance is the backbone of public health, because good decision-making is impossible without good data. Unfortunately, many countries — including resource-rich countries — don’t robustly track outbreaks of antibiotic-resistant pathogens in farmed animals, nor do they share data on antibiotic use in farmed animals. By developing early warning systems for detecting antibiotic resistance in aquatic environments, rapid response efforts involving ecologists, veterinarians and epidemiologists can be mobilized as threats arise to avert public health disasters.

Meanwhile, the aquaculture industry should continue to innovate. Genetic technologies and new vaccines can help prevent rampant infections, while also improving growth efficiency that could allow for more humane conditions.

For consumers, the best way to stay healthy is simple: Seek out antibiotic-free seafood at the supermarket, and cook your fish (sorry, sushi lovers).

There’s no doubt that aquaculture is critical for feeding a hungry planet. But it must be done responsibly.

Neil M. Vora is a practicing physician and the executive director of the Preventing Pandemics at the Source Coalition.

Science

A SoCal beetle that poses as an ant may have answered a key question about evolution

The showrunner of the Angeles National Forest isn’t a 500-pound black bear or a stealthy mountain lion.

It’s a small ant.

The velvety tree ant forms a millions-strong “social insect carpet that spans the mountains,” said Joseph Parker, a biology professor and director of the Center for Evolutionary Science at Caltech. Its massive colonies influence how fast plants grow and the size of other species’ populations. That much, scientists have known.

Now Parker, whose lab has spent 8 years studying the red-and-black ants, believes they’ve uncovered something that helps answer a key question about evolution.

In a paper published in the journal “Cell,” they break down the remarkable ability of one species of rove beetle to live among the typically combative ants.

The beetle, Sceptobius lativentris, even smaller than the ant, turns off its own pheromones to go stealth. Then the beetle seeks out an ant — climbing on top of it, clasping its antennae in its jaws and scooping up its pheromones with brush-like legs. It smears the ants’ pheromones, or cuticular hydrocarbons, on itself as a sort of mask.

Ants recognize their nest-mates by these chemicals. So when one comes up to a beetle wearing its own chemical suit, so to speak, it accepts it. Ants even feed the beetles mouth-to-mouth, and the beetles munch on their adopted colony’s eggs and larvae.

However, there’s a hitch. The cuticular hydrocarbons have another function: they form a waxy barrier that prevents the beetle from drying out. Once the beetle turns its own pheromones off, it can’t turn them back on. That means if it’s separated from the ants it parasitizes, it’s a goner. It needs them to keep from desiccating.

“So the kind of behavior and cell biology that’s required to integrate the beetle into the nest is the very thing that stops it ever leaving the colony,” Parker said, describing it as a “Catch-22.”

The finding has implications outside the insect kingdom. It provides a basis for “entrenchment,” Parker said. In other words, once an intimate symbiotic relationship forms — in which at least one organism depends on another for survival — it’s locked in. There’s no going back.

Scientists knew that Sceptobius beetles lived among velvety tree ants, but they weren’t sure exactly how they were able to pull it off.

(Parker Lab, Caltech)

Parker, speaking from his office, which is decorated in white decals of rove beetles — which his lab exclusively focuses on — said it pays to explore “obscure branches of the tree of life.”

“Sceptobius has been living in the forest for millions of years, and humans have been inhabiting this part of the world for thousands of years, and it just took a 20-minute car ride into the forest to find this incredible evolutionary story that tells you so much about life on Earth,” he said. “And there must be many, many more stories just in the forest up the road.”

John McCutcheon, a biology professor at Arizona State University, studies the symbiotic relationships between insects and the invisible bacteria that live inside their cells. So to him, the main characters in the recent paper are quite large.

McCutcheon, who was not involved with the study, called it “cool and interesting.”

“It suggests a model, which I think is certainly happening in other systems,” he said. “But I think the power of it is that it involves players, or organisms, you can see,” which makes it less abstract and easier to grasp.

Now, he said, people who study even smaller things can test the proposed model.

Noah Whiteman, a professor of molecular and cell biology at UC Berkeley, hailed the paper for demystifying a symbiotic relationship that has captivated scientists. People knew Sceptobius was able to masquerade as an ant, but they didn’t know how it pulled it off.

“They take this system that’s been kind of a natural history curiosity for a long time, and they push it forward to try to understand how it evolved using the most up-to-date molecular tools,” he said, calling the project “beautiful and elegant.”

As for the broader claim — that highly dependent relationships become dead ends, evolutionarily speaking, “I would say that it’s still an open question.”

Science

Video: Why Mountain Lions in California Are Threatened

new video loaded: Why Mountain Lions in California Are Threatened

By Loren Elliott, Gabriel Blanco and Rebecca Suner

February 9, 2026

-

Politics6 days ago

Politics6 days agoWhite House says murder rate plummeted to lowest level since 1900 under Trump administration

-

Indiana1 week ago

Indiana1 week ago13-year-old rider dies following incident at northwest Indiana BMX park

-

Indiana1 week ago

Indiana1 week ago13-year-old boy dies in BMX accident, officials, Steel Wheels BMX says

-

Alabama4 days ago

Alabama4 days agoGeneva’s Kiera Howell, 16, auditions for ‘American Idol’ season 24

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoTrump unveils new rendering of sprawling White House ballroom project

-

San Francisco, CA7 days ago

San Francisco, CA7 days agoExclusive | Super Bowl 2026: Guide to the hottest events, concerts and parties happening in San Francisco

-

Culture1 week ago

Culture1 week agoTry This Quiz on Mysteries Set in American Small Towns

-

Massachusetts1 week ago

Massachusetts1 week agoTV star fisherman’s tragic final call with pal hours before vessel carrying his entire crew sinks off Massachusetts coast