Oregon

25 plants to draw native bees to Oregon gardens in honor of National Pollinator Week

Honeybees get all the attention, but they aren’t the only bees pollinating our gardens. In Oregon, over 500 native bees are out doing their part, too

As National Pollinator Week (June 17-23) nears, it’s time to bring them into the limelight. Many are beautiful – like the metallic sweat bee with emerald green head and thorax or the cute ball of fluff called a digger bee. They’re also docile, leaving people alone as they move from plant to plant gathering and depositing pollen.

Without insect pollinators cucumbers, apples and berries – along with thousands of other plants – wouldn’t bear fruit or vegetables. That makes conservation vital, said Gail Langellotto, entomologist and professor in the OSU College of Agricultural Sciences. To help make this happen she surveyed bee species from 24 Portland-area gardens, all tended by a cadre of OSU Extension master gardeners.

For this Garden Ecology Lab research project, Langellotto visited the gardens monthly to collect bees. They are then sent to experts at the American Museum of Natural History in New York for identification. The information collected enhances the Oregon Bee Atlas, a volunteer program charged with surveying the whole state.

“We want to generate a species list from Oregon gardens,” she said. “Other states have them, but we don’t know what native bees appear in Oregon. If we know which bees we have, we can determine their health and how we might help them.”

The Oregon Bee Atlas is one of several projects undertaken by the Oregon Bee Project, a collaboration of OSU Extension, the Oregon Department of Agriculture and the Oregon Department of Forestry. The project was undertaken by mandate of the Oregon Legislature after 50,000 bumble bees were killed five years ago when blooming linden trees in a parking lot were sprayed with pesticide.

“The Oregon Bee Project is about putting tools in people’s hands to literally build and care for native bee pollinator habitat, and gardeners are really at the forefront of that effort,” said Andony Melathopoulos, OSU Extension bee specialist and leader of OSU’s participation in the project.

On the Oregon State campus in Corvallis, Al Shay, a horticulture instructor at OSU, has led a campaign to show how to be kind to bees. He and his students build pollinator houses and plant accompanying gardens. They’ve installed them, not only on campus, but around town at the Corvallis Fire Department downtown, the Methodist Church and Sunset Park.

Shay hopes to have 20 more pollinator houses placed in public locations by next year, some accompanied by gardens.

“As we become more urbanized, it makes sense to provide habitat for pollinators,” he said. “We’re trying to get the word out and tell people to do the same things in their own backyards.”

Langellotto agrees. Part of her research is looking at volunteer gardens and noting what conditions pollinators thrive in. They use mapping and geographic information systems (GIS) to see what’s adjacent to the gardens – highways, forests, waterways, shopping centers, farms or any other land use that may be nearby.

“We expect gardens can be a fantastic habitat for bees,” she said. “Gardens can be incredible for conservation in general. If we’re able to identify garden features that help conserve bees we will communicate that and hopefully get gardeners to do some of these things.”

Plant selection is the biggie, she said. One tiny garden in her study is right up against Interstate 5 but had the second most number of bees of the 24 they surveyed. And most likely it will rank first or second in diversity.

“It suggests that intentional plant choices make a difference,” Langellotto said. “If you plant it, they will come.”

Native plants play a large role, but there are many exotics that do just as well. Look for single flowers with flat faces; fluffy double flowers deter bees. Choose a diversity of plants and have some that bloom at different times of the year – some plants like Oregon grape even bloom in winter.

Plant in swaths. Planting something is better than nothing, but you’ll notice that a single plant rarely has pollinators visiting.

One of the most important things gardeners can put into practice is limiting use of pesticides (check with your local Extension office or Master Gardeners to determine what is wrong with your plants before treating).

Native bees are solitary and live in ground nests, so leave a little bare ground for them.

“Bees are crucial to the food we eat,” Langellotto said. “They help maintain the plants we love. Something as simple as planting a sustainable garden can help with conservation.”

Top 25 plants for attracting pollinators

Oregon grape flowers bloom at Camassia Nature Preserve in West Linn, a 26-acre natural area managed by international environmental nonprofit The Nature Conservancy. Jamie Hale/The Oregonian

Bloom winter through early spring (February through April)

Vine maple (Acer circinatum): Native, deciduous large shrub or small tree that can be trained to a single or multi-trunked form. Good as an understory plant under tall evergreens. Zone 7.

Tall Oregon grape (Berberis aquifolium, formerly Mahonia): The Oregon State flower, this native evergreen shrub busts out with huge can’t-miss-them clusters of yellow flowers. Zone 7.

Camas (Camassia spp.): A native bulb with tall foliage and an even taller stalk of blue flowers.

Crabapple (Malus floribunda): Deciduous tree with masses of pink or white blooms, followed by red berries. Zone 4.

Willow (Salix spp.): Many different types of this deciduous shrub or tree, depending on which you choose. Some have a graceful weeping form. Zone 6.

Bloom spring through early summer (April through June)

Western serviceberry (Amelanchier alnifolia spp.): Native deciduous shrub or small tree with star-shaped white flowers followed by maroon-purple berries. Zone 4.

Borage (Borago officinalis): An annual herb with fuzzy foliage and delightful clusters of blue flowers; will reseed year to year. An ancient plant that is used for medicinal purposes.

California lilac (Ceanothus spp.): Tough evergreen shrub with knobs of blue flowers that cover the plant like a blanket. Drought tolerant. There are many cultivars. Zone 7-8.

Tickseed (Coreopsis spp.): An adaptable perennial prized for its bright yellow flowers, often with a red eye, and drought tolerance. Various zones.

Geranium (Geramium spp.): These perennials are not the blustery blooming annual plants that we’re all familiar with; they are tough, hardy perennials with five-petaled flowers in many shades of purple and pink. Zone 3.

Globe gilia (Gilia capitata): A native annual that’s very adaptable to different situations. Sports puffs of lavender flowers. May reseed.

Lupine (Lupinus spp.): Tall spikes of flowers make these perennials, annuals, and biennials distinctive plants in the garden. The most common is blue, but hybrids run the gamut from pink and red, yellow and white and even bi-colors. Zone 3.

Chokecherry (Prunus virginiana): A native deciduous shrub or small tree with pendulous white flowers and attractive bark. Zone 2.

California poppy (Eschscholzia californica).Staff

Bloom mid- to late summer (July through September)

Blue giant hyssop (Agastache foeniculum and spp.) A drought-tolerant perennial with rods of lavender-blue flowers. Smells like anise when crushed. Zone 4.

California poppy (Eschscholzia californica): The familiar, friendly orange perennial wildflower that’s as tough as it comes. Drought tolerant. Zone 5.

Oregon gumweed (Grindelia stricta or integrifolia): A native perennial bearing school-bus yellow, daisylike flowers. Great for the beach. Zone 8.

Sneezeweed (Helenium autumnale): Another native, yellow-blooming perennial with daisylike flowers and a big cone in the center. Zone 3.

Showy tarweed (Madia elegans): This yellow-blooming native plant is an annual herb, and a beautiful one at that. Flowers are centered with a red ring.

Catmint (Nepeta x faassenii): A pretty, pest-free perennial with gray-green, fragrant foliage and spikes of small flowers in shades of blue and purple. Zone 5.

Russian sage (Perovskia atriplicifolia): Airy clouds of lavender flowers distinguish this heat-loving, low-water perennial. Zone 4.

Phacelia (Phacelia spp.): A fast-growing annual with fernlike foliage topped with fascinating blue flowers that unfurl in a fiddlehead shape. Zone 7.

Stonecrop (Sedum spp.): There are any species of this succulent, both tall and low. Groundcovers normally put out small yellow flowers; tall have blooms in shades of pink. Drought tolerant. Various hardiness, some as low as Zone 4.

Bloom late summer to fall (September through November)

Michaelmas daisy (Aster amellus): An easy-to-grow perennial with daisylike flowers in various shades of purple and pink. There’s even a white one. Zone 4.

Goldenrod (Solidago canadensis): A native perennial with abundant sprays of sunshine yellow. Zone 4.

Douglas aster (Symphyotrichum subspicatum): An adaptable, very-long blooming native perennial with lavender-blue, daisylike flowers. Zone 5.

– List compiled by Signe Danler, OSU Horticulture Department

Oregon

Oregon Parks and Recreation considers changes to e-bike rules

Oregon Parks and Recreation Department (OPRD) has launched a project to consider new rules for electric bike use in campgrounds, beaches and other parks facilities.

The effort comes as e-bike use has skyrocketed statewide and a new law that clarified e-bike types was passed by the Oregon Legislature last session.

You’ll recall in 2017 we reported on an unfortunate wrinkle in OPRD rules that meant bikes with battery motors were technically not allowed on the popular bike paths throughout the State Park system. That legal glitch was cleared up in 2018 when the State Parks Commission approved a new administrative rule that allowed e-bikes to be ridden on trails and roads wider than eight feet unless otherwise posted.

Now they seek to re-evaluate the rules to account for different types of e-bikes and different trail types. According to OPRD, the resulting change in rules is expected to be made later this year and could, “expand, limit or continue where e-bikes can be used.”

(Keep in mind, Oregon parks are managed with Oregon Administrative Rules (OAR), not the Oregon Vehicle Code.)

House Bill 4103 passed the legislature earlier this year. It brought Oregon in line with national standards and adopted a three-class system: Class 1 includes bikes that can go up to 20 mph with only pedal and battery power; Class 2 includes bikes that can go up to 20 mph with a throttle; and Class 3 includes bikes that can go up to 28 mph with only pedal-assisted power.

“OPRD’s current e-bike rules do not account for these differences between e-bike classes, so now is an ideal time to revisit current regulations and assess whether changes are appropriate,” reads an OPRD webpage.

A new survey is the first step in the public outreach process that will help inform which new rule(s) OPRD ultimately adopts. The survey asks respondents what type of activities they do in parks, how often they encounter e-bikes, and whether, “e-bikes on trails impact your recreational experience.” Another question: “Do you have any concerns about e-bikes sharing trails?” makes it clear that this process will tilt heavily toward ameliorating complaints from some park users that some e-bike riders don’t ride with respect to others.

I sincerely hope OPRD does not over-regulate e-bikes. They should focus on regulating behaviors, not bicycle types, just like they do with other types of vehicles. Any type of blanket exclusion of a particular type of e-bike could risk limiting access t recreational activities for many Oregonians.

The survey is open through August 31st. Take it here.

Stay tuned for the public comment period and any other news on this front.

Oregon

Oregon’s unemployment rate remained higher than the national average in May

The Oregon Employment Department reported 4,000 more jobs

Posted:

Updated:

PORTLAND, Ore. (PORTLAND TRIBUNE) — Oregon’s economy continues to add jobs as the statewide unemployment rate held steady at 4.2% in May.

The Oregon Employment Department reported a gain of 4,000 last month after a revised gain of 2,400 in April. It released its monthly report on Thursday, June 20.

The unemployment rate remained at 4.2% for the fourth consecutive month; the national average for May was 4%. Oregon’s monthly unemployment rate has been at 4.2% or less since October 2021.

Health care and social assistance gained 1,900 jobs in May, for a total of 16,200 (5.7%) in the past 12 months. All four components in this category have shown growth. But private-sector jobs overall have gained a net of just 3,500 — for .2% growth — as manufacturing dropped 3,700 jobs, retail trade 3,400, and construction 2,200.

Retail trade (800) and construction (400) led job losses for May.

Read more at PortlandTribune.com.

The Portland Tribune and its parent company Pamplin Media Group are KOIN 6 News media partners

Oregon

Are Meta, Google, and Amazon the Monsters of Oregon’s Deep Blue Sea? | Essay

In 2020, Edge Cable Holdings, a Facebook subsidiary, was burying a new fiber-optic cable into the seabed near Tierra Del Mar, Oregon. Working beneath a rugged mixture of basalt rock mounds, unconsolidated sands, and sandstone bedrock, the company’s drilling operation went awry. Stalled out, they ditched their metal pipes, drilling fluids, and other construction materials in the ocean: Out of sight, out of mind.

When Oregon’s Department of State Lands learned of the abandonment, they ordered Edge Cable Holdings and Facebook (now Meta) to pay a fine. But the damage was done. Two sinkholes formed along the installation path and most of the materials will remain lodged in the seafloor forever. These items, and thousands of gallons of drilling fluid, pose an ongoing risk to the surrounding seafloor ecosystem. Despite public outrage, the company returned to complete the cable in 2021, with debris from the first attempt still lodged in the seabed.

The cable was not the first to slither into Oregon’s stretch of the Pacific Ocean, and it’s by no means the last. Big technology companies including Amazon, China Mobile, and Google are flocking to Oregon’s coastline to land transpacific fiber-optic cables. Most recently in August 2023, the Department of State Lands approved a 9,500-mile fiber-optic cable connecting Singapore, Guam, and the United States.

What has transformed Oregon into an undersea cable hotspot—and how is the installation process affecting a vibrant ocean ecosystem? The explanation resides in tax breaks, swift permitting processes, cheap energy, vast amounts of open land for data centers, and a historical carelessness for the environment shared by the state and tech companies alike.

Fiber-optic cables transmit data with pulses of light through thin glass fibers. In 2022, they provided over 98 percent of the world’s internet services and international phone calls. There are more than 745,000 miles of submarine fiber-optic cables in operation around the world—that’s enough cable to wrap around the Earth’s equator more than 29 times. It’s the work of cables, not satellites, that connect us on a global scale.

Although undersea cables seem to be torn from the pages of a futuristic science fiction novel, they aren’t a new technology. The first functional telegraph cables crossed the Atlantic seabed in the 1860s.

The Pacific, a wider and deeper ocean basin and therefore more difficult to wire, received its first transoceanic cable in 1902. By the early 1900s, the global seafloor hosted around 200,000 miles of telegraph cables. And by the 1950s, that number reached nearly 500,000 miles of telephone and telegraph cables, with fiber-optic cables first joining the mix in the 1980s.

What has transformed Oregon into an undersea cable hotspot—and how is the installation process affecting a vibrant ocean ecosystem?

Back then, many transpacific cables landed in California, Washington, and British Columbia, where they could link up with transportation hubs and industrial centers on land. That began to change in 1991, when Oregon landed its first transpacific fiber-optic cable. Called the North Pacific Cable, the privately owned line connected Oregon to Alaska and Japan. In the three decades since, the state has welcomed a new fiber-optic cable every four or five years, in tandem with new data centers—large, high-security buildings that store rows of servers. These servers host the internet’s millions of websites.

There are significant onshore incentives for cable owners to land their lines in Oregon. Oregon’s “enterprise zones” tax-exemption program allows individual towns to negotiate property tax breaks for big construction projects, thereby saving companies millions of dollars each year. In exchange for the tax breaks, tech companies provide a small influx of jobs and tax revenue to small communities hurting from the decline of the timber industry. In 2015, Oregon lifted its cap on enterprise zones to attract even more data centers, just as more cables arrived along the shoreline.

Consider Meta, which owns a 4.6 million square foot data center complex in rural Prineville, Oregon. Although it’s far from the ocean in a former timber town, this data center connects to a network of underground fiber-optic cables, including the controversial undersea cable installed near Tierra del Mar. In 2015, the Oregonian reported that the data center complex received $30 million in tax breaks that year alone.

For Meta, as well as Amazon, Google, and Apple, Oregon offers a win, win, win.

So who exactly is losing?

The coastal ecosystem. During installation, it’s standard practice to bury cables multiple feet into the seabed to avoid snags by fishing vessels. The most common burial method is plowing, during which a remotely operated vehicle cuts a ditch into the seafloor and inserts the cable into the trough. Another method, jetting, uses high-pressure fluids to liquefy sediments on the seafloor, easily slicing a clean line into the seabed in which the cable can burrow. Companies also use directional drilling to bore diagonally into the seabed from the shore. All of these methods squish or displace any worms, crabs, sea stars, urchins, anemones, corals, or sponges living within the trenching path.

Once installed, submarine cables settle into the seafloor ecosystem. In search of hard substrate to call home, marine life will colonize the cable’s exterior. After a few decades of service, cable owners have historically abandoned their lines in the ocean, a decision that is both cheaper for companies and often results in less disturbance for colonizing species. Inert but not biodegradable, most dead cables will sit in the ocean indefinitely, hidden from the public who is usually none the wiser.

The 2020 Facebook/Edge Cable Holdings abandonment prompted Oregon to pass a 2021 law instituting firmer planning and decommissioning regulations for new undersea cable projects. Still, the increasing scrutiny doesn’t appear to be slowing the big tech companies. As Amazon builds its recently approved line to Guam and Singapore, the tech giant is also building another data center in Umatilla, Oregon, a small town on the Columbia River.

Data centers are no better for terrestrial environments than submarine cables are for marine. The buildings suck significant amounts of power from the grid. Oregon’s renewable energies, like hydroelectric dams on the Columbia River, can’t cover data centers’ growing energy demands, meaning utility providers must tap into fossil fuels and increase their greenhouse gas emissions. Despite Oregon’s efforts to decrease the state’s carbon footprint, some regions are moving backward in the fight against climate change. Big tech companies, and their big buildings, are spurring that reversal.

Across Oregon, communities and ecosystems are confronting the physical impacts of a world that runs on internet—impacts that our regulatory systems have yet to reckon with.

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoSwitzerland's massive security effort at the Ukraine peace conference

-

News1 week ago

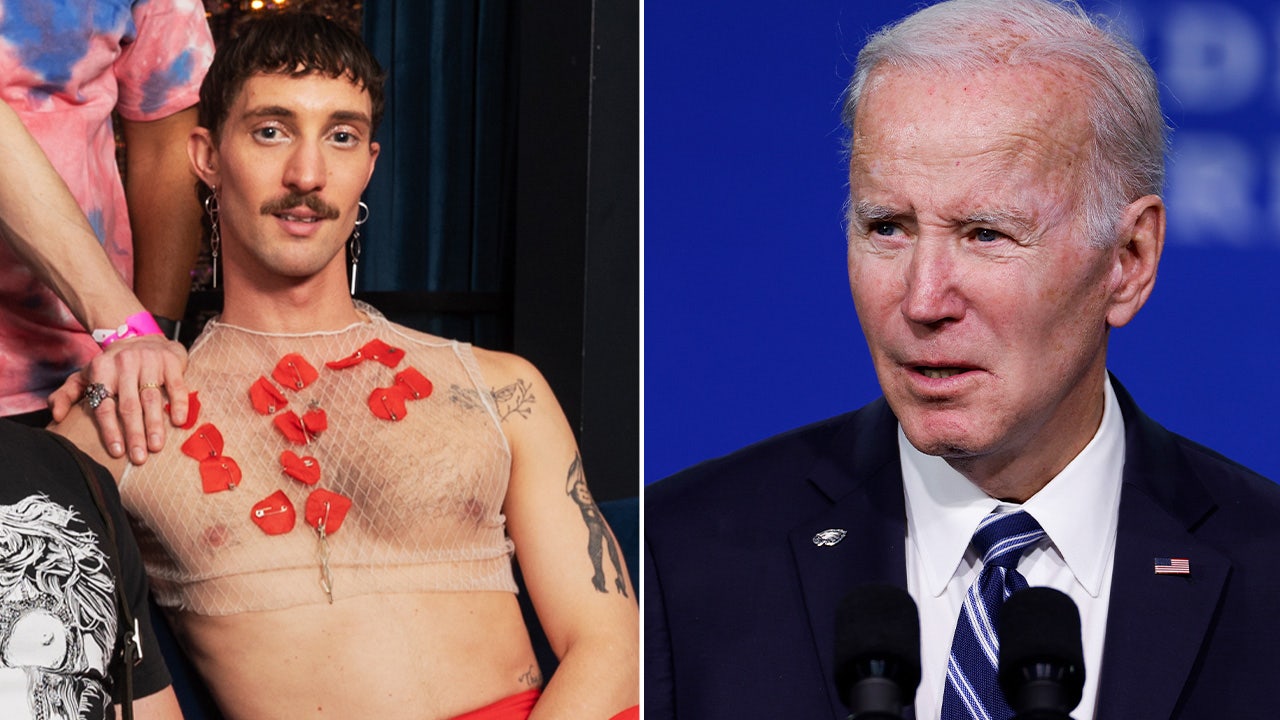

News1 week agoJoe Biden, Barack Obama And Jimmy Kimmel Warn Of Another Donald Trump Term; Star-Filled L.A. Fundraiser Expected To Raise At Least $30 Million — Update

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoIt's easy to believe young voters could back Trump at young conservative conference

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoSwiss summit demands 'territorial integrity' of Ukraine

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoProtesters in Brussels march against right-wing ideology

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoRussia-Ukraine war: List of key events, day 842

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoBiden looks to capitalize on star-studded Hollywood fundraiser after Trump's massive cash haul in blue state

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoJudge rules Missouri abortion ban did not aim to impose lawmakers' religious views on others