Sports

Mountain West Conference commissioner laments 'national negative attention' amid SJSU trans player controversy

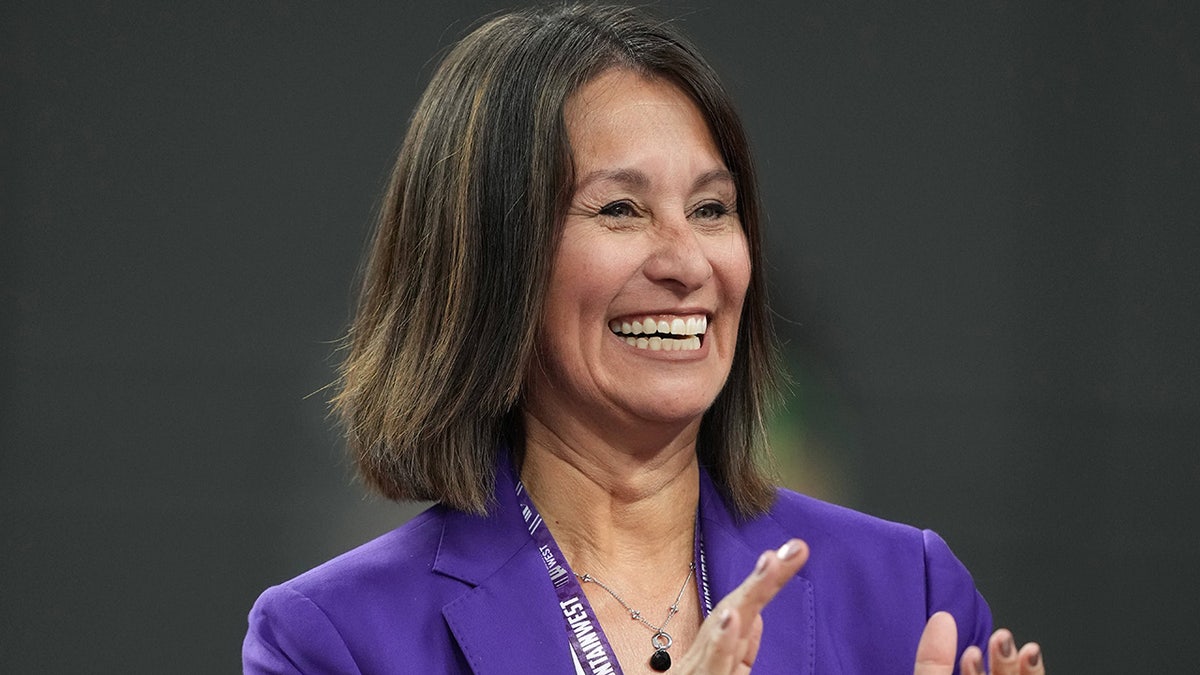

Mountain West Conference Commissioner Gloria Nevarez spoke on Thursday about the drama surrounding the San Jose State women’s volleyball team, as several schools have decided to forfeit games against the squad because of a transgender athlete on its roster.

Nevarez said at Mountain West basketball media days that the forfeits against the Spartans is “not what we celebrate in college athletics.”

Blaire Fleming, #3, a redshirt senior at San Jose State University, plays as an outside and right-side hitter on the women’s volleyball team. (San Jose State University)

“It breaks my heart because they’re human beings, young people, student-athletes on both sides of this issue that are getting a lot of national negative attention. It just doesn’t feel right to me,” Nevarez told The Associated Press.

Boise State, Southern Utah, Utah State and Wyoming decided to forfeit games against San Jose State. Some Nevada players have chosen to sit out the game, but the school is playing in the match regardless, saying state law bars forfeiture.

NEVADA COLLEGE SAYS IT WON’T CANCEL VOLLEYBALL MATCH AGAINST SCHOOL WITH TRANSGENDER PLAYER DUE TO STATE LAW

Blaire Fleming, a transgender athlete, has played three seasons at SJSU after previously playing at Coastal Carolina. (San Jose State University)

“I know what our team is going to do, and we are going to have integrity,” Wolf Pack captain Sia Liillii told The Reno Gazzette Journal. “I think this is the toughest thing our team has gone through, but I’m just glad I have so many brave young women behind me, and I get to be the captain of this team.”

Nevarez suggested trans inclusion in women’s sports was an issue she was still “learning a lot about.”

Mountain West Conference Commissioner Gloria Nevarez reacts during the Mountain West Championship at Allegiant Stadium in Las Vegas on Dec. 2, 2023. (Kirby Lee-USA TODAY Sports)

“I don’t know a lot of the language yet or the science or the understanding nationally of how this issue plays out,” she added. “The external influences are so far on either side. We have an election year. It’s political, so, yeah, it feels like a no-win based on all the external pressure.”

The Associated Press contributed to this report.

Follow Fox News Digital’s sports coverage on X, and subscribe to the Fox News Sports Huddle newsletter.

Sports

Indiana’s Curt Cignetti has ignited a fire: ‘This guy is just different’

BLOOMINGTON, Ind. — Four words came to Curt Cignetti’s mind as he tried to follow along from 800 miles away the path of a tornado that was closing in on his youngest child.

“What have I done?”

It was April 27, 2011. Cignetti was at a function at Indiana University of Pennsylvania (IUP), where he had recently started as head football coach, taking a 60 percent pay cut from the $250,000 he was making on Nick Saban’s staff at Alabama. His family was still back in Tuscaloosa finishing out the school year. Son Curtis was an Alabama student and was bunkering down on campus as the tornado — which would end up killing 64 people, six of them university students — passed nearby.

Cignetti’s wife, Manette, was three and a half hours south in Mobile for daughter Carly’s high school state tennis tournament. That left the youngest, daughter Natalie, at a friend’s house in a neighborhood that was about to be hit directly. Manette got Natalie on the phone and screamed at her to take cover. She and her friend’s family did, in the basement, under a table, as the house was moved off its foundation — a few hundred yards from a house that was completely obliterated.

“You’re just sick to your stomach, you’re helpless,” Manette said. “Meanwhile, Curt has to be present at this event and is just about having a heart attack trying to figure out what’s going on.”

The Cignettis were safe and soon reunited. But the scare was just the latest prompt for those four words: “What have I done?”

A coach approaching 50 doesn’t leave a job as a recruiting coordinator and receivers coach at one of the top programs in the sport to take over a struggling Division II outfit. That’s a sharp detour from a steady climb in a tough business, as the pay cut suggests. Manette rejected the idea out of hand.

But Cignetti always wanted to be a head coach, like his father, and believed he could win at IUP, like his father. He took the dubious leap. And those early doubts, intensified by the realization that IUP’s football resources had gone backward over decades, soon gave way to validation.

As Cignetti’s Indiana Hoosiers prepare to host Nebraska at sold-out Memorial Stadium on Saturday, in the program’s biggest game in years, he sits at 160 games coached. He has won 125 of them. When he was introduced as IU’s coach in December, after successful stints at James Madison, Elon and IUP, four words came to mind after a question about the difficulty of succeeding at historically hapless Indiana.

“I win. Google me,” Cignetti said.

So far, that’s all he’s done.

Cignetti’s teams usually win because he usually outperforms the coach on the other sideline. For as blunt and confident as he can be, he won’t say it quite like that. But those who have seen him do his work will.

“He and his coaches give you all the answers, so you just know you’re going to win on game day,” said Todd Centeio, a quarterback who transferred from Colorado State to James Madison for his final year of eligibility in 2022 and won Sun Belt Offensive Player of the Year.

“I don’t know how he does it, I just know that I trust it,” said Indiana tight end Zach Horton, one of several prominent Hoosiers who followed Cignetti from James Madison.

“Just highly intelligent and raised in the game,” said Duke coach Manny Diaz, who worked with Cignetti at NC State.

“He has an absolutely incredible football mind,” said Jeff Bourne, the athletic director who hired Cignetti to James Madison from Elon, and whose retirement preceded Cignetti’s move to IU. “Watching his scouting of an opponent and preparation of a game plan was just really remarkable. You’d go into some games feeling like, ‘Well, I’m not sure about this one,’ and then we’d win and you’d realize how much it had to do with the preparation of the coaching staff. The way he analyzes opponents and finds ways to beat them, I saw it so many times and it was absolutely amazing.”

He saw it from the other side on Oct. 6, 2018, when Cignetti’s Elon Phoenix came to Harrisonburg, Va., as massive underdogs against FCS No. 2-ranked James Madison and pulled a 27-24 shocker. A couple of months later, JMU coach Mike Houston was off to East Carolina and Cignetti was Bourne’s choice to replace him and lead JMU’s successful transition to the FBS.

Indiana is 6-0 and outscoring opponents by 32.7 points per game. (James Black / Icon Sportswire via Getty Images)

Elon went a modest 14-9 in Cignetti’s two seasons there — but that was a turnaround from 12-45 in the previous five seasons. Cignetti’s formula has worked everywhere, and it starts with an eye for the game and a willingness to use both eyes until the lids get heavy to find an edge.

“He’s always in his office, always watching film,” said Indiana linebacker Aiden Fisher, another JMU transfer making an immediate splash with the Hoosiers.

Cignetti said the film projector is on “98 percent of the time” when he’s in that office. Then he goes home to the teal recliner that has survived all 35 years of the Cignettis’ marriage.

“All he does is sit in his chair and work,” Manette said.

That’s part of the formula. So is frank, honest talk, which Cignetti has found works with recruits and players alike. That’s where his late father, Frank Cignetti Sr., is apparent in his coaching style.

“He was a great man, a great leader, an up-front guy,” Cignetti said of his father, who passed away in 2022 at age 84. “He’d always tell you what was on his mind. You may not like it, but he would tell you. Usually, to be your best, you’ve got to hear things you don’t like sometimes.”

Frank Sr. grew up in Pittsburgh, his parents having moved from Italy, his father a coal miner.

“Everyone was a coal miner or in the steel mill, that’s what everyone did where I was from,” said Cignetti, the oldest of four kids of Frank Sr. and Marlene. “Athletics was the way out.”

Frank Sr. was an NAIA All-America end at IUP, and his coaching career wound from the high school ranks to West Virginia, where Bobby Bowden hired him to coach the offensive backfield in 1970. When Bowden left for Florida State in 1976, Frank Sr. succeeded him as head coach.

In 1978, Frank Sr. hired a young West Virginia native named Nick Saban to coach defensive backs. He also battled a rare form of cancer, had his spleen removed, was given chemotherapy and last rites twice, and ultimately survived. In 1979, he welcomed his eldest son as a quarterback on the team and was fired after the season with a 17-27 record in four years.

“Let’s face it, I’ve got a little chip on my shoulder and some of it is that I had to go to IUP to be a head coach, that I’ve been underestimated my whole life,” Cignetti said. “But the Cignetti name drives me too.”

Cignetti stayed as a backup at West Virginia for his final three seasons of eligibility under Don Nehlen, who he said “was great to me,” and then his coaching career got going as Frank Sr. found his sweet spot. After several years as athletic director at IUP, he took over head coaching duties in 1986 and had a tremendous 20-year run — 182-50-1 with several deep Division II playoff runs, two to the championship game.

Frank Jr. played for his father at IUP and embarked on a coaching career that has included several NFL stops and two stints at hometown school Pittsburgh. Curt started at Pitt as a grad assistant in 1983 and then coached quarterbacks and tight ends there in the 1990s for Johnny Majors and Walt Harris. Manette, who met Curt in her hometown of Indiana, Pa., while in pharmacy school, shared in supporting their young family as a pharmacist.

Pitt is where Cignetti’s recruiting skills — evaluation and relentless pursuit — got him his first recruiting coordinator gig. He carried that to Chuck Amato’s staff at NC State and also coached Philip Rivers there.

“Cig is just one of those coaches that checks every box and you could see all of it back then,” said Noel Mazzone, who worked with Cignetti as Amato’s offensive coordinator in 2003 and 2004.

The Saban connection came back around when he left the Miami Dolphins for the Alabama job in early 2007. Saban had stayed in touch with Cignetti over the years and now wanted him to coordinate recruiting and coach receivers for the Crimson Tide. That meant pursuits such as eventual Heisman winner Mark Ingram, coaching players like Julio Jones and winning a national championship.

“My experience with coach Saban, I can’t even begin to tell you, like, even just after a year with him, how much I learned about running an organization,” Cignetti said. “From A to Z. Every day was like a doctoral class. It was so structured, so organized. He had a philosophy on everything. Everything was just airtight. I learned a ton.”

One thing he learned: Saban liked to look outside to fill coordinator openings, such as when he hired Jim McElwain from Fresno State to be OC in 2008. After four seasons, with his 50th birthday approaching, Cignetti was feeling the urgency.

“I really didn’t want to be another 58-year-old assistant coach bouncing around looking for another job, you know what I mean?” he said. “I’d seen those guys. I’d grown up in the business, I’d followed careers and I didn’t want to be in that situation eight to 10 years from then. I wasn’t a coordinator and I felt like to that point I was always the next guy. I’d been passed over. But I always felt like I could be a good head coach. I wasn’t not going to be a head coach.”

IUP called in December 2010.

“I said, ‘No, you can’t take it,’” Manette said. “I just wasn’t going backward.”

Cignetti turned it down. That was that. Except weeks later, the job still wasn’t filled. Cignetti got another call.

“He looks at me and says, ‘I just really want to be a head coach,’” Manette said. “What am I gonna do? Keep him from his dream? He gave me that look and it was, ‘Oh crap. OK. OK. Let’s go. Let’s do it.’”

It was a much easier decision when Indiana came calling after last season after James Madison finished 11-1 to bring Cignetti’s five-year record there to 52-9.

The Indiana of Pennsylvania move meant Manette resuming work as a pharmacist, in advance of both daughters following up college with medical school — both are doctors now — while Curtis got into medical sales. He and his wife, Amy, have provided the Cignettis with their first two grandkids, Sophia and Isabelle.

Indiana football is a family affair for the Cignettis. (Courtesy of Manette Cignetti)

The Indiana of Bloomington move meant Cignetti’s salary multiplied by nearly seven times — from $677,000 last year at James Madison to $4.25 million per year at IU before bonuses. He’s a 63-year-old coach who has never been a coordinator for a power-conference school and has just two FBS head coaching seasons under his belt. And he was the easy, clear No. 1 choice for Indiana athletic director Scott Dolson.

“From the first time we talked, it was, ‘This guy is just different,’” Dolson said. “People don’t believe me, but I don’t think he’s cocky. He’s really not. He just tells you exactly how he feels.”

That meant frank conversations about administrative support during the interview process and a feeling after talking to IU President Pamela Whitten that it was strong. Cignetti already knew the Big Ten’s media rights deals would extend IU’s resources edge over most athletic departments in years to come. And that a hapless football program isn’t an option for any institution that wants to stay in that neighborhood.

Dolson knows that, too, which is why his department launched a study to help direct the revival of Indiana football while Tom Allen was still the coach. The focus was on “like schools,” Dolson said, that had found football success. Put another way, basketball schools: Kentucky, Kansas, Duke and North Carolina.

There are major differences among that group, but all have found varying measures of success with good coaching hires. Though Kansas is struggling this season, Lance Leipold has given the program energy and fits the profile of an older coach who worked his way up at lower levels. The “do-everything” nature of those jobs can be an advantage, as Dolson observed this season when Cignetti had a full travel plan ready early in advance of a win at UCLA.

GO DEEPER

‘If you can coach, you can coach’: So why don’t more lower-level coaches make the big time?

The study produced several traits of an ideal coach, including someone who was currently a head coach; a proven evaluator who had been a recruiting coordinator at some point; and an offensive-minded coach known in particular for developing quarterbacks. Cignetti was an obvious choice before they spoke. Then they did.

“It was like he had our blueprint and our plan literally in front of him when I was talking to him,” Dolson said. “Everything that was important to us was important to him.”

Still: Indiana?

This is the program with the most losses in Division I history, 713, and the worst winning percentage by far in Big Ten history at .421. It is to the Big Ten as Vanderbilt is to the SEC, though Indiana does at least have two conference titles to its name — in 1945 and 1967.

Allen provided a brief burst of hope with his 14-7 run in 2019 and 2020. Terry Hoeppner had the energy to change the narrative in the early 2000s before tragically dying of brain cancer after two seasons. Bill Mallory had some solid teams in the 1980s and 1990s. Lee Corso brought personality. No one has gotten out of the place with more wins than losses since Bo McMillin managed that feat in 1947.

Cignetti had no use for that history. But he felt it almost immediately.

“I could tell this place had been beaten down in terms of a lot of people just didn’t think it was possible,” he said. “I was just shocked at how everybody on the outside thought it was impossible to get anything done here.”

That’s the genesis of the Pittsburgh-accented “Google me.” Cignetti had heard enough chatter about the hopelessness of Indiana football by the time he got to his introductory presser.

“That just killed me — that’s typical, straight Cig, right?” Mazzone said.

“He really is humble, but he had to light a fire,” Manette said.

“I just had to set an expectation level that this is who we’re gonna be, and we’re not gonna permit anything else,” Cignetti said. “We’re winning here. There are no self-imposed limitations. I had to show that confidence, not just to the players, but to the fans.”

Then it was on to quickly fixing a roster that had just lost several defensive starters and all but one offensive starter. Cignetti brought in 22 transfers, 13 from James Madison. He leaned on those guys, several of them instantly some of IU’s best players, to get everyone else ready for what was coming.

Practices would be short and relentlessly efficient. Life would be good for those who do the right things and prepare. These coaches would have the formula for winning, weekly.

“It didn’t take long for everyone to get on board,” Horton said, and the Hoosiers have won all six games, the best start since 1967, entering a moment of revelation against Nebraska.

The schedule gets much tougher from here, with Washington, Michigan and a trip to Ohio State coming up soon. But the quality of the football — spearheaded in large part by Ohio transfer quarterback Kurtis Rourke — is undeniable. The Hoosiers are inventive and explosive on offense, and they stop the run and get after the quarterback on defense, with JMU transfer Mikail Kamara already at five sacks. The response from fans and boosters, Cignetti said, has been “over the top.”

“The NIL has grown very significantly from what it was, and it needed to,” he said. “I pushed that hard. I pushed the envelope on that, and people responded.”

Already, this program has better facilities than some may realize — both stadium end zones were enclosed in the past 15 years at a combined cost of $91 million, plus $2 million in locker room renovations in 2019. Indiana athletics had $166.8 million in reported revenues in the most recent budget year, No. 13 in the country and No. 5 in the Big Ten. Indiana University has the second-largest alumni base in the country, about 900,000 people.

So there’s money to be found in case Cignetti’s salary needs to double or so, soon after it got multiplied by seven. As more of college football finds out who he is, his team is in position to contend for a spot in the first 12-team College Football Playoff. The Hoosiers should have a reasonable shot at every game on the schedule but the trip to Ohio State.

Hoosiers fans may need to see more to believe something like that is possible, but so far in 10 months, they’ve seen nothing to declare it isn’t.

“When that time comes to get into that Playoff bid, we’ll look up and see our logo up there,” Fisher said, “and then we’ll get to preparing for that game just like it’s another game week.”

That confidence. That’s what Cignetti’s done.

(Top photo: Michael Hickey / Getty Images)

Sports

Dodgers bullpen shows their 'pitch each other up' culture at critical Game 4 moment

Most fans from a sold-out crowd of 43,882 had filed out of Citi Field by the eighth inning Thursday night, the Dodgers pulling away in the final innings of a 10-2 National League Championship Series Game 4 victory over the New York Mets that moved them to within one win of the World Series.

But only two innings earlier, the joint was jumping, the chants of “Let’s go, Mets!” grew louder and louder, and the Mets, who had staged one dramatic comeback after another this month, were one big swing away from making it a one-run game.

Three batters later, the stadium went so quiet you could hear Grimace, the team’s unofficial mascot, crying in his purple fur, the Mets unable to put a dent in the nearly impenetrable back end of the Dodgers’ bullpen despite loading the bases with no outs.

“Oh yeah,” reliever Evan Phillips said, when asked if he noticed how quickly Citi Field went silent. “I think that was really deflating for them. For us to be able to stop that kind of momentum, even with the five-run lead, was huge.”

Phillips, who has not given up a run in 14⅓ innings over 11 playoff appearances dating to 2021, replaced starter Yoshinobu Yamamoto with one out and a runner on first in the bottom of the fifth and the Dodgers leading 5-2.

The right-hander, making his first NLCS appearance, struck out Mark Vientos, who had homered off Yamamoto in the first, with a 97-mph fastball and got Pete Alonso to ground into an inning-ending forceout.

The Dodgers pushed the lead to 7-2 in the sixth on Mookie Betts’ two-run homer, but the Mets threatened to take a huge chunk out of that cushion when Brandon Nimmo and Starling Marte singled and J.D. Martinez walked to open the bottom of the sixth.

Pitching coach Mark Prior came to the mound to chat with Phillips, who probably didn’t need to be reminded of the two grand slams the Mets hit this postseason, one by Francisco Lindor in the division series-clinching win over Philadelphia, the other by Vientos in New York’s Game 2 win over the Dodgers.

Dodgers reliever Evan Phillips speaks with pitching coach Mark Prior during the sixth inning Thursday against the Mets.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times)

“Mark coming out there gave me a second to just reset and reshift my focus back to what I need to do, which is execute pitches and get guys out,” Phillips said. “He didn’t tell me anything I didn’t already know, because we work really hard to have a good plan.

“The biggest thing was there were contact guys coming up, guys who it’s really hard to get swing-and-miss against, so just try to execute good pitches and hopefully come down on the right side of it.”

Phillips jumped ahead of Jose Iglesias with two strikes and the Mets second baseman whiffed at a 96-mph, up-and-away fastball.

Pinch-hitter Jeff McNeil fouled off four pitches before taking an 85-mph sweeper below the zone for a ball. Phillips then came up and in with a 95-mph sinker, and McNeil flied out to shallow center field, Nimmo holding at third.

With Phillips’ pitch count at 34, manager Dave Roberts summoned right-hander Blake Treinen to face pinch-hitter Jesse Winker, who put a charge into a 95-mph fastball and sent a line drive to the warning track in right field, where Betts made the inning-ending catch.

“It sounded pretty loud, but I think I missed the barrel just enough,” Treinen said. “I think the biggest thing in those situations is, don’t try to think about the what-ifs and just focus on who’s in the box. Try to execute your pitches.

“Certainly, I got away with one tonight against Winker. The bases were loaded, it was a 7-2 game, and if he had gotten into that one even better, it could have been a 7-6 game. But it wasn’t. I’m grateful we were able to put up a zero.”

Treinen, who missed most of the last two seasons because of shoulder injuries, threw a scoreless seventh to push his scoreless streak to 21⅓ innings dating to Aug. 24, 15⅓ innings over his last 15 regular-season games and six scoreless innings in five playoff games.

“Sounds like Blake Treinen, doesn’t it?” Phillips said. “It’s really great to see him kind of back to normal form. He’s someone that I respect a lot. He’s been through a tough couple years of injuries and trying to bounce back from that. And I think this year you’re starting to see, you know, a lot of those old feels come back for him.”

Phillips, Treinen and Michael Kopech have thrown most of the high-leverage innings, but the bullpen as a whole has given up just 12 earned runs in 45 innings of nine playoff games for a 2.40 earned-run average. Take away the five runs starter Landon Knack gave up in two relief innings in the Game 2 loss, and the bullpen ERA would be 1.47.

“The culture in the ‘pen is they just pitch each other up,” Roberts said. “Regardless of when they get the baseball, they’re ready when called upon, which is huge.”

A relief corps that also has gotten significant contributions from left-handers Alex Vesia and Anthony Banda and right-handers Daniel Hudson and Ryan Brasier has helped move the Dodgers to the brink of their 22nd World Series and fourth in eight seasons.

“What I love most about our group down there is we’re all in it together,” Phillips said. “It’s been really fun to watch each guy kind of have their piece in this postseason, handing off to one guy after another, in any situation. Our mentality is that when the phone rings, we just do our job and get outs.”

Sports

Ryder Cup ticket prices have never been higher. That’s a real problem for golf

It should not be this hard to like golf.

Even if you can chuckle at a golf company putting a YouTube channel logo on a driver and charging $700, accept that the polo in the pro shop can easily cost upwards of $100, rationalize the cost and hassle of the trip to the top-tier golf resort, or nap your way through umpteen “playing through” commercial breaks on the Sunday afternoon broadcast, at least live professional golf has generally been good.

You walk around or find a good spot and take a seat. And either way, you see the best players in the world in competition closer than just about any other sport can offer. Most of the time it’s an excellent value — I can buy a ticket right now for Sunday at the 2025 U.S. Open at Oakmont Country Club outside of Pittsburgh for $185.

That would not get me past the gates on Tuesday at the 2025 Ryder Cup, three full days before the competition actually begins. And if I actually wanted to see Scottie Scheffler, Jon Rahm and the rest of the best players in the world in an alternate shot match? The PGA of America has made it beyond the limits of most golf fans.

A single ticket for each match day at the Ryder Cup at Bethpage Black in New York will cost $749.51.

Seven hundred and forty-nine dollars and 51 cents. For one ticket. For one day.

It’s beyond. It just is. I do not want to hear about supply and demand, or how much tickets go for on the resale sites. Rory McIlroy is not Taylor Swift, and face value for tickets to her shows is nowhere near that high.

The Ryder Cup is a massive event with ticket prices that now reflect that. (Adam Cairns / USA Today)

That’s four times the prices at the last U.S.-hosted Ryder Cup, at Whistling Straits in 2021. It’s $255.27 to attend practice days, and $423.64 for Thursday’s practice round, opening ceremony and celebrity competition. Has the PGA of America gone mad?

They rationalize that these tickets are actually Ryder Cup+ tickets, a marketing ploy that means I can get all the food and non-alcoholic drinks I desire. How good are these hot dogs if I have to pay an extra $500 for them? And can you bring a case of them around to the parking lot? Because I’ll need to bring them home to feed the family for a while. Throw in some buns, yes.

It will cost a family of four $3000 to attend the Ryder Cup. I’m not arguing everything should be for everyone, but that feels excessive, no?

I expect the crowd at Bethpage Black, as a result, to be a bizarre mix. On one hand, it’ll be overly corporate, because those charge cards don’t blink. Those fans also do not care what’s happening on the course, because they’re more concerned with making deals under the tents. Then you’ll have the crowd that has scraped together the cash to get in, and feels that paying $1,000 (once you include parking, merchandise and alcoholic drinks) entitles them to do and say anything they damn well please. Should be fun!

Normal golf fans are outraged. They should be. We have put up with years of bickering and lawsuits, and desperate decisions that aided bank accounts and made the product worse. Purses have never been higher, but the same can be said for the costs of sponsoring and airing a PGA Tour event. That means more commercials and less golf shots, and we wonder why TV ratings are down week to week.

But at least the live product was good. It still is — if you live near a pro golf stop on any tour, you should go. You’ll probably enjoy it.

But the Ryder Cup is the Ryder Cup. It’s the only event we have that can rival the Masters, and it brings out a sense of nationalism in all of us. The stakes feel so high that the anticipation for every shot is heightened, and the atmosphere around that first tee box can take your breath away.

I hope you can experience it one day. I hope you’ve been lucky enough to be able to go to Bethpage and not worry about the cost. But if you can’t, I hope what has been done here is only an outlier, and not a sign of what is to come.

(Top photo: Alex Burstow / Getty Images)

-

Entertainment1 week ago

Entertainment1 week agoHold my beer can: Museum says a worker thought unique art installation was trash

-

Entertainment1 week ago

Entertainment1 week ago'The Office' star Jenna Fischer reveals private breast cancer battle: 'I am cancer free'

-

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25673932/462754179_560996103109958_6880455562272353471_n.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25673932/462754179_560996103109958_6880455562272353471_n.jpg) Technology6 days ago

Technology6 days agoMeta suggests AI Northern Lights pics are as good as the real thing

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoScammers exploit grief with fake funeral streaming on Facebook

-

Lifestyle5 days ago

Lifestyle5 days agoIs the free speech debate dead? Plus, the devil! : It's Been a Minute

-

Technology5 days ago

Technology5 days agoThis 3D-printed Texas hotel is shaking up the construction industry

-

Lifestyle5 days ago

Lifestyle5 days agoHow one Afro-Colombian community honors their ancestry

-

Business2 days ago

10 million pounds of meat and poultry recalled from Trader Joe's and others in latest listeria outbreak