Oklahoma

Oklahoma’s maternal death rate has risen sharply, new report shows

The death rate among Oklahoma women having children has risen sharply, a new state report says. The primary cause: the COVID-19 pandemic.

Although Oklahoma’s maternal death rate had declined prior to 2018, a report from the Oklahoma Maternal Health Task Force shows the number of deaths increased from 25.2 per 100,000 live births for the 2018-20 reporting period to 31 deaths per 100,000 in the 2019-21 reporting period.

A maternal death is defined as the death of a pregnant woman or a death that took place within 42 days after the termination of pregnancy, “from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management.” That definition excludes deaths for accidental or incidental causes.

Nationwide, the report said the maternal mortality rate for the United States was more than three times the rate of other developed countries.

According to the Oklahoma State Department of Health, records from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show Oklahoma persistently ranks among the states with the worst rates of maternal deaths in the nation.

Between 2017-2019, Oklahoma’s maternal mortality rate was 23.5 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births. This is above the national average of 20.1 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births.

Why maternal deaths might be so high in Oklahoma

The most likely contributor to the increase in maternal mortality at both the national and state levels was the emergence of COVID-19.

“Several groups were, and continue to be, at greater risk of severe illness due to COVID-19, including those who are immunocompromised, have certain disabilities, or have underlying health conditions, such as those who are pregnant or recently pregnant,” the report said. “The greatest number of deaths, about 25% of maternal deaths in 2020 and 2021, were related to COVID-19.”

Additionally, the greatest increase in maternal deaths occurring in the later months of 2021 was likely due to an outbreak of the Delta variant, which surfaced in July of that year.

The pandemic also affected maternal health in other ways, the report said. A reduction in health care services, transportation and child care challenges — all centered on the fear of contracting COVID-19 — could have contributed to reduced access to health care, delayed or forgone pregnancy care and worsened outcomes,

Grading Oklahoma: A look at maternity health in the Sooner State

Despite the bad numbers, state health officials said encouraging women to get regular checkups and increasing efforts to address maternal risk factors could help reduce future deaths.

“Every interaction with any health care provider should be used as an opportunity to assess for opportunities to educate individuals on healthy behaviors and link them with resources,” Erica Rankin, a spokesman for the state Health Department, said.

Rankin said new and expectant mothers could improve their health by having chronic conditions treated and under control before getting pregnant and getting the necessary vaccinations.

The state’s infant mortality rate, too, continues to remain high. A new study by the March of Dimes puts the state’s infant mortality rate at 7.1 deaths per 1,000 births, well above the nationwide number of 5.4 deaths per 1,000 births.

Infant mortality rate in Oklahoma is also high

Although state health experts agree that challenges remain in the effort to reduce maternal and infant mortality rates, other issues may be harder to address. Rankin said several international studies show better maternal and infant outcomes occur when midwives and doulas are included in the maternity care team. She said that as of July 1, Medicaid now covers doula care.

Rankin said numerous studies showed there are currently 44 delivering hospitals in the state and 77 counties. “About a third of these hospitals are located in the metropolitan areas of the state, leaving many counties without a hospital that delivers babies and has maternity care providers,” she said.

The March of Dimes report said state officials could improve health outcomes for both mothers and infants by adopting paid family leave policies and by creating a perinatal quality collaborative to identify and improve quality-care issues in maternal and infant health care.

Oklahoma

Thunder receive NBA championship rings, raise title banner: Check it out

NBA teams with most pressure in 2025-26

Breaking down which NBA teams are under the most pressure to win going into the 2025-26 season.

The 2025-26 NBA season started Tuesday night in Oklahoma City as Shai Gilgeous-Alexander and the Thunder hosted Kevin Durant and the Houston Rockets.

Before tip-off, the Thunder celebrated their 2024-25 NBA championship season and raised their first title banner since the organization moved to Oklahoma City.

OKC players were greeted by NBA commissioner Adam Silver as they were introduced to the home crowd and received their championship rings.

Here’s how the players reacted to the championship rings and banner being raised:

Thunder receive championship rings, raise title banner

Here’s a detailed view of the Thunder’s new bling:

Oklahoma

Interim study held over misuse of ALPR cameras

OKLAHOMA CITY (KFOR) — An Oklahoma Representative says the state’s Automated License Plate Readers (ALPR) are being misused by law enforcement.

When News 4 spoke with Rep. Tom Gann (R-Inola) in August, he claimed law enforcement was abusing the purpose of ALPRs, which is used to make sure Oklahoma drivers are insured.

Gann and others presented how ALPR cameras are infringing on peoples 4th Amendment right.

He says if action isn’t taken soon on governing how law enforcement is using these cameras, the citizens of Oklahoma will end up paying for it.

“These are serious violations of people’s rights and this comes from a lack of internal controls,” Gann said. “We have feds using local cops passwords to do immigration surveillance with flock cameras. It is the fact that he can pass his password around to anybody he wants to, to get onto this system is a problem. We need internal controls otherwise we create more victims with these flock cameras.”

License plate readers have been legal in Oklahoma since 2018.

The cameras intention was to enforce the Compulsory Insurance Law, making sure drivers aren’t on the road without insurance.

“Under the appropriate use, this is a good thing,” Shena Burgess, Attorney said. “We want people to have insurance. If people have insurance, then our insurance rates go down. I was all for that part.”

Oklahoma’s Uninsured Vehicle Enforcement Diversion (UVED) Program says these cameras have helped greatly, drastically reduced the number of uninsured drivers on the road.

Over the past seven years, we’ve realized a significant reduction in uninsured vehicles operating on Oklahoma roadways. UVED offers Oklahomans a chance to achieve compliance without law enforcement interaction, without criminal charges, without court costs, and without time

lost from work, school, or home.Spokesperson for Uninsured Vehicle Enforcement Diversion (UVED)

However, Burgess says those cameras are being used for much more.

“The Tulsa County Sheriffs Office testified in a federal court that they use the Automated License Plate Readers all the time, for purposes that have nothing to do with whether or not the vehicles have insurance,” Burgess said.

Gann says this has led to instances where law enforcement have pulled over the wrong person thinking they were a suspect in a crime.

“We have victims of mass surveillance out there already,” Gann said. “When tag numbers are misread, you have people like this, where her and her 12 year-old sister were held at gunpoint because of a misread on a tag.”

He also mentions that this is a violation of your 4th Amendment right.

“The 4th Amendment offers security to a person when they place themselves in a constitutionally protected area albeit home, office, hotel room or automobile,” Gann said.

Burgess says this is a major concern for her, and what this could mean for future court cases.

“Once challenges start happening, civil lawsuits are going to follow,” Burgess said. “It is going to be our citizens who end up paying for this.”

The meeting was supposed to be a joint study between Gann and Rep. Tim Turner (R-Kinta), but Gann told Turner he would be taking up the allotted time, so Turner decided to withdraw his study.

They say they will continue to work toward a solution over the misuse of ALPR cameras.

Oklahoma

Critics Say CompSource Plan Will Hurt Policyholders – Oklahoma Watch

A hush-hush plan to convert CompSource Mutual to a stock company has been challenged by a policyholder and a law firm who argue the proposal for Oklahoma’s largest workers’ comp insurer amounts to a raid on CompSource’s $1 billion surplus for an aggressive expansion plan.

A class-action lawsuit, brought by Oklahoma City law firm Whitten Burrage, ongoing for four years, alleges that CompSource’s $1 billion surplus holdings have accrued, at least in part, from decades of bundling of phantom policies that never pay out on claims.

Speaking through statements issued by a public relations firm, CompSource claimed to have no intention to sell shares in the new company. However, the statements masked a complicated reorganization scheme that would give a subsidiary of the newly formed company the ability to issue shares.

An Oklahoma Watch investigation revealed that prior to the conversion plan being submitted to the Oklahoma Insurance Department for approval, CompSource had begun selling multiple lines of insurance in Oklahoma, and had been approved to do business in multiple lines of insurance in at least 10 other states, with applications submitted to dozens more.

Constitutional attorney Bob Burke, who said he has been a CompSource policyholder for more than 40 years, expressed dire concerns over both the portion of CompSource’s cash holdings that would be transferred from policyholders to the new corporation and the potential 49% of shares of the new company that could become available to outside investors.

“Somebody is going to make a zillion dollars,” Burke said.

Burke expressed doubt about the sincerity of CompSource’s claim that no shares will be sold for six months after the conversion plan is approved.

“That’s part of the story,” Burke said. “But their documents reveal that it is an intermediate step. They are misleading, because they don’t tell the rest of the story.”

The Wheatley Mine No. 4 Explosion

On Oct. 27, 1929, an explosion at Wheatley Mine No. 4 in McAlester took the lives of 30 coal miners. Lawsuits stemming from the accident resulted in the dissolution and sale of Samples Coal Co., which operated the mine. Less than a month later came Black Tuesday, the beginning of the 1929 stock market crash.

Four years later, seemingly in response to horrific workplace accidents like the McAlester disaster and because the Great Depression resulted in insurers refusing to write workers’ comp policies despite employers’ statutory obligation to provide benefits, the precursor to CompSource, the State Insurance Fund, was set up with an initial infusion of $25,000 of government money, the equivalent of about $623,000 in 2025.

For decades, the State Insurance Fund remained the insurer of last resort for Oklahoma businesses required to carry workers’ comp coverage but unable to secure a policy from a private company. Eventually rebranded CompSource, the organization operated as a quasi-governmental public option, which was never intended to seek profits for itself.

If the conversion plan succeeds, workers’ comp rates could increase for about one-third of the state’s workers’ comp policies, critics said.

Another Explosion, More Lawsuits

On Sept. 29, 2006, Jack Foran, an employee of Okemah-based Double M Construction Company Inc., died in an explosion in Labette County, Kansas, when a piece of machinery hit an inadequately marked 10-inch natural gas pipeline.

Foran’s widow, Oneta Foran, sued Double M when CompSource refused to pay on Part Two of their coverage; CompSource argued that Part Two applied only if an employer either desired to bring about an injury or had knowledge that such an injury was substantially certain to occur.

Subsequent to that action, Oneta Foran’s attorney, Terry West of Shawnee, executed an about-face and represented Double M in an effort to launch a class-action lawsuit, claiming that CompSource’s Part Two coverage was illusory.

In other words, the plaintiffs argued, CompSource was selling insurance with no intention of paying out on claims, slowly accumulating a huge cash reserve.

In 2011, a district judge in Oklahoma County denied class certification, ruling entirely in favor of CompSource.

Everything is Owned by Policyholders

Two years later, lawmakers considered privatizing the company. Instead, they decided to convert the former State Insurance Fund into CompSource Mutual, a mutual insurance company owned by policyholders.

That effort was challenged in court by Tulsa attorney and one-time leader of the Oklahoma Senate, Stratton Taylor. Taylor argued in Tulsa Stockyards v. Clark that a move of $265 million of state agency funds to a mutual company violated a prohibition against gifts of public money, among other constitutional wrongs.

“Somebody’s going to make a zillion dollars.”

Bob Burke

Taylor lost the Tulsa Stockyards decision at the Oklahoma Supreme Court, which approved the mutualization and upheld previous rulings that found that CompSource funds did not belong to the state; everything the newly minted CompSource Mutual owned was actually owned by its policyholders.

A New Class Action

In 2020, a decade after class-action certification was denied in the Double M case, Whitten Burrage won class certification for an ongoing lawsuit that asks the same question of illusory Part Two coverage. The suit alleges that $100 million has been wrongly collected since 1978 in sales of a policy upon which CompSource never intended to pay out.

Oklahoma Watch’s investigation discovered an application submitted by CompSource to secure licensing in Texas. The application attests to a vigorous effort to fight the class-action lawsuit, but acknowledges unpredictable vulnerability.

“The ultimate disposition of (the class action) could have a material adverse effect on CompSource Mutual’s financial condition,” the application reads, adding that it was not possible to accurately estimate the potential financial liability.

Flying Under the Radar

CompSource Mutual’s latest transformation is in stark contrast to a bruising legislative battle and subsequent Oklahoma Supreme Court decisions more than a decade ago, when lawmakers considered selling off the company.

The decade since it became a mutual insurance company has been good for CompSource Mutual. The company more than doubled its surplus, from $428 million in 2015 to $971 million in 2024, according to annual reports filed with the Insurance Department.

In the past five years, the dollar value of premiums written by CompSource Mutual for workers’ comp policies averaged about $202 million each year. At the same time, annual claims averaged $133 million per year.

The latest reorganization became possible after lawmakers in 2022 passed Senate Bill 524. The bill directed the state Insurance Department to develop a residual market plan by 2024. That effectively ended CompSource’s role as the default workers’ comp insurer if a company couldn’t find required coverage in the private market.

Then, House Bill 3090, passed in 2024, set up the process by which a mutual insurance company could convert to a stock company. CompSource requested the bill, but it said the legislation also applied to other mutual insurance companies in Oklahoma.

CompSource said in written statements that policyholders’ contract and voting rights would remain largely unchanged if it converts to a stock company, with any capital raised for policyholders’ benefit.

A Surprise Meeting

In August, a notice appeared without fanfare on the Insurance Department website, announcing a hearing in a few days’ time for public comments on the CompSource conversion plan. While documents reveal that the plan had been in the works for months or even years, critics cried foul, saying the effort failed to properly notify CompSource policyholders.

At the Aug. 28 hearing, only two members of the public showed up to offer comments on the plan: Burke and Whitten Burrage attorney Randa Reeves.

Reeves offered details on CompSource’s history of selling what plaintiffs claim is illusory coverage.

“The damage model that we’re talking about is in excess of $100 million in premiums that were wrongfully charged by CompSource to the policyholders dating back to 1978 for coverage that has never been paid,” Reeves said.

Burke laid out the broader stakes of the conversion plan.

“Now, CompSource has asked the insurance commissioner for permission to convert to a stock insurance company,” Burke said. “In other words, nearly half a billion in assets could be owned by outside stockholders.”

CompSource President and Chief Financial Officer Steve Hardin offered a starkly different characterization of the plan.

“The conversion offers CompSource Mutual the ability to better grow and respond to future needs, challenges and opportunities in a rapidly changing insurance industry while preserving mutuality and the ability to operate with a focus on the long-term interests of the policyholders,” Hardin said, reading from a prepared statement at the hearing.

Following the Aug. 28 hearing, the CompSource stock conversion decision fell wholly into the hands of Insurance Commissioner Glen Mulready, a former lawmaker who was first elected as insurance commissioner in 2018. Term-limited, Mulready will not again face the electoral pressures of reelection. Mulready’s decision on the CompSource conversation plan is expected any day. If he approves, the plan will go before policyholders for final approval.

Paul Monies has been a reporter with Oklahoma Watch since 2017 and covers state agencies and public health. Contact him at (571) 319-3289 or pmonies@oklahomawatch.org. Follow him on Twitter @pmonies.

-

World2 days ago

World2 days agoIsrael continues deadly Gaza truce breaches as US seeks to strengthen deal

-

Technology2 days ago

Technology2 days agoAI girlfriend apps leak millions of private chats

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoTrump news at a glance: president can send national guard to Portland, for now

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoUnionized baristas want Olympics to drop Starbucks as its ‘official coffee partner’

-

Politics2 days ago

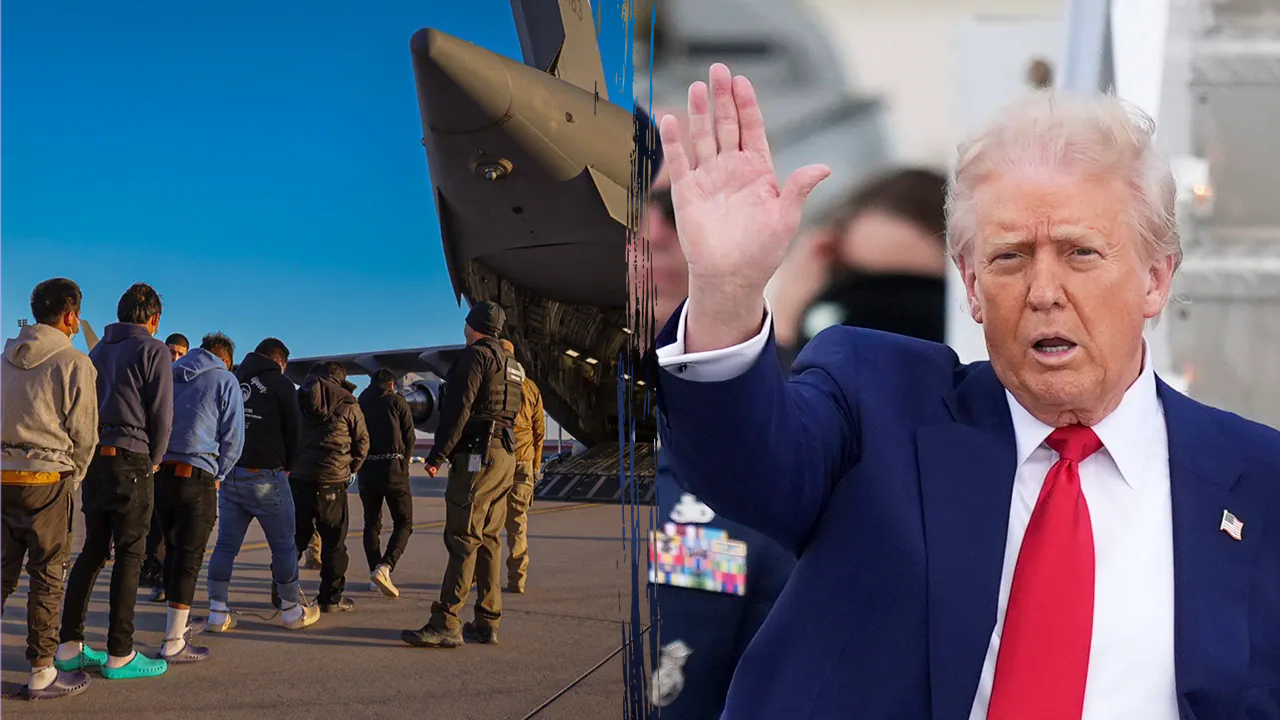

Politics2 days agoTrump admin on pace to shatter deportation record by end of first year: ‘Just the beginning’

-

Science2 days ago

Peanut allergies in children drop following advice to feed the allergen to babies, study finds

-

News1 day ago

News1 day agoBooks about race and gender to be returned to school libraries on some military bases

-

News21 hours ago

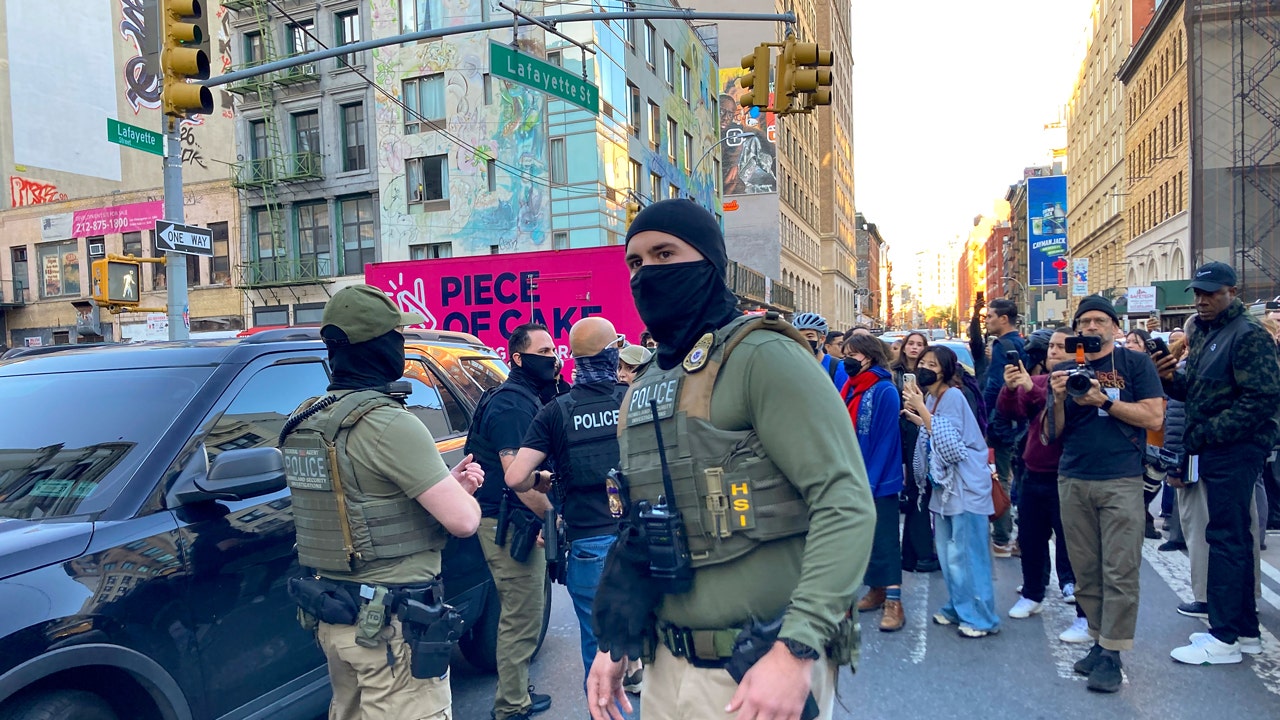

News21 hours agoVideo: Federal Agents Detain Man During New York City Raid