Oklahoma

Oklahoma Has a New Plan for Putting Christianity Back in the Classroom. Except It’s Not New at All.

Like the award-winning teacher he once was, the Oklahoma state superintendent of public instruction, Ryan Walters, arrived at his presentation with props in tow. Speaking to the Oklahoma Board of Education on June 27, Walters announced his controversial mandate requiring the Bible in public schools while posing with a stack of five books. Among them? A brand-new copy of Martin Luther King Jr.’s Our God Is Marching On. A copy of The U.S. Constitution: A Reader, a collection compiled by Hillsdale College professors that represents the separation of church and state as a “popular misunderstanding.” And finally, three Bibles, including a copy of The Founders’ Bible, which interleaves the religious text with Christian nationalist writings by discredited “historian” David Barton. As visual aids to Walters’ announcement, these volumes spoke volumes.

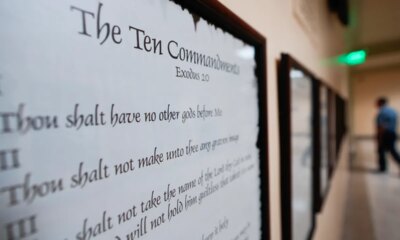

At the June Board of Education meeting, Walters justified his decision by describing the Bible as a “necessary historical document” that has inspired American leaders such as Dr. King, whose legacy conservative politicians have increasingly manipulated to their advantage. Going beyond the text of his written memorandum, which states simply that Oklahoma schools must “incorporate the Bible … as an instructional support,” Walters announced that effective this fall, “every teacher, every classroom in the state, will have a Bible in the classroom and will be teaching from the Bible.” In late July, he doubled down, issuing a set of instructional support guidelines that decree that “a physical copy of the Bible, the United States Constitution, the Declaration of Independence, and the Ten Commandments [must be provided] as resources in every classroom.”

Walters has leaned heavily on historically inaccurate claims that the Bible is, as he stated at the June meeting, “one of the most foundational documents used for the Constitution.” Yet Walters’ repeated insistence on a Bible in “every classroom” shows that his ideological roots lie not with 18th-century framers like Thomas Jefferson—who placed a library, not a church, at the center of his University of Virginia—but rather with evangelical mass media organizations formed during the 19th century. Like once influential publishers including the American Bible Society and the American Sunday-School Union, Walters understands that the power of print has as much to do with the physical presence of books as it does with the intellectual work of reading.

The American Bible Society was founded in 1816 as a national organization with a single goal: distributing the Bible. Early adoption of cutting-edge printing technologies enabled the society to produce its own inexpensive Bibles on an unprecedented scale. Buoyed by its rapid progress, in 1829 the group launched a campaign to provide a Bible to every American family that needed one—a plan the organization dubbed “General Supply.”

Two other national evangelical publishing organizations—the American Sunday-School Union and the American Tract Society—soon followed suit with similar projects. As media historian David Paul Nord has documented, combined general supply efforts of the 1830s alone resulted in the publication of approximately 1 million Bibles, 15 million religious tracts, and more than 500,000 Sunday school books.

By attempting to circulate publications “in every part of the land,” including regions where print was scarce, general supply programs provided Americans with inexpensive reading materials and contributed to the increase of national literacy rates. But 19th-century evangelical publishers also had another, less generous goal in birthing American mass media: ousting books they didn’t like from readers’ hands.

All three national organizations hoped that mass supply of religious print would stimulate new demand. They also solicited support for their activities by fueling 19th-century fears about the mental and physical effects of reading “improper books.”

At the forefront of this anxious politics was the Sunday-School Union, which argued that secular books including “novels” were “sweet poison” for children. For the union, whose leaders viewed the Bible as “essential to the proper training of the young,” the solution lay in publishing vast quantities of religious children’s texts and introducing them into schools—including schools unaffiliated with the organization. By doing so, union leaders believed they could “force out of circulation those [books] which tend to mislead the mind.”

Such statements advance a logic of physical replacement as much as they insist on the persuasive power of God’s word. If you could just get the right books in the same room as young readers, the Sunday-School Union reasoned, “good little books” would take up space, money, and attention that might otherwise go toward “bad books.”

This 19th-century history raises questions about what, exactly, Walters hopes to achieve by requiring a Bible in “every” Oklahoma classroom. Because by “every classroom,” he really means every classroom.

Although Walters’ July guidelines detail only how the Bible might be incorporated into humanities instruction, he has stated in interviews that the Bible will also be integrated into the study of math and science. Walters has argued that the Bible should be taught to explain its influence on Western civilization and the history of the United States—a proposal, it’s worth noting, that mistakes the text for its reception history. But his insistence on placing physical copies of the Bible in “every classroom” indicates that the intended scope of his program is much broader, even as he has insisted that classroom Bibles are “not to be used for religious purposes such as … proselytizing.” As 19th-century religious organizations well knew, getting religious books in as many places as possible is itself a form of evangelical activity. By implementing his 21st-century version of general supply, Walters promises to use the Bible to occupy both valuable instructional time and the public school classroom as site.

Like the paper-obsessed Donald Trump, who inspired the June mandate and has himself published a Bible better suited for display than reading, Walters understands that books make good props for the art of hijacking attention. That he wants Bibles in the “classroom” rather than a more obvious place for books—the school library—also channels the desire of his evangelical forebears to control what children read.

If 19th-century language about “vice-engendering, lust-influencing, and soul-destroying literature” sounds oddly familiar, you’re not wrong. In Oklahoma, Walters has joined efforts to ban LGTBQ+ children’s books and campaigned for the removal of “pornographic” material from school libraries. Walters’ Bible mandate may appear to divert attention from the state Supreme Court’s late-June rejection of a proposed Catholic charter school supported by taxpayers—an initiative that Walters supported. But the Bible mandate also follows an equally important Oklahoma Supreme Court decision made earlier in June, which checked Walters’ authority over school libraries by determining that decisions about library book selection should remain with local school boards. Although the court shot down Walters’ attempts to wrest control over school libraries, by demanding the inclusion of the Bible in the “classroom” it seems that Walters has found a way to bypass librarians—and put children in the same room as his preferred reading—after all.

As the school year approaches, Walters has yet to answer questions about which Bible edition he would require should his plan be allowed to proceed. Hopefully it’s not The Founders’ Bible, which Barton peppers with out-of-context quotes from historical figures including Thomas Paine, a Deist who once described the Bible as a “book of lies.” Obvious legal questions aside, the presence of Barton’s Christian nationalist book at the Board of Education meeting sends a damning message about Walters’ ability and willingness to uphold basic educational standards. This message has not been lost on Oklahoma school districts, several of which have stated publicly that they will not change their curricula despite the July guidelines. In a subtle clapback to Walters, Jenks Public Schools in suburban Tulsa have insisted they will use only “approved resources aligned to the Oklahoma Academic Standards” in their classrooms.

In the wake of Walters’ mandate, advocacy organizations have stressed that “public schools are not Sunday schools.” But Walters would do well to take a cue from the American Sunday-School Union, which, for all its flaws, valued children’s “desire for knowledge” and believed, without a doubt, that free access to school libraries was of “vital importance” to the next generation’s future.

Oklahoma

Oklahoma County commissioners weigh state audit of jail trust amid detention center woes

OKLAHOMA CITY, OKLA. (KOKH) — An investigative audit into the Oklahoma County Criminal Justice Authority; it’s something the Oklahoma County Board of Commissioners is considering.

Fox 25 has been covering issues with the Oklahoma County Detention Center for years, from failed inspections to staffing issues and missed paychecks.

The issues had members of the Jail Trust recommending last June they undergo a performance review. Now, in a letter recently issued, county commissioners are asking State Auditor Cindy Byrd to look into the county Criminal Justice Authority, also known as the jail trust. But whether it’s tied to those ongoing issues remains unclear.

“I really wouldn’t know. I wouldn’t know where to begin with that. I just wouldn’t even want to speculate, honestly,” said Commissioner Myles Davidson.

Commissioner Davidson told FOX 25 if the audit were to happen, it wouldn’t be cheap.

“To go into a budget that we’re extremely tight on, and start adding hundreds of thousands of dollars, and time, these audits don’t happen overnight. I don’t know that we would have an answer to any question we could possibly ask before the budgetary cycle is over,” said Davidson.

Davidson said that cycle ends June 1. Instead, he’s suggesting they look into existing audits to see if there’s any useful information there first.

“I would simply say that we need to look at the audits that have been submitted already to the state auditor that the jail trust has already paid for, and then if we have questions about those, we need to bring in that auditing agency and question them. We do have the authority to do that,” Davidsons said.

However, Davidson isn’t sure they have the authority to request this audit.

“When it comes to statute, we have to have it lined out, expressly in statute that we have this authority, and every county commissioner across the state has to abide by that,” he said.

Davidson said they’ll be meeting Monday to find out whether or not they do have the authority to request this audit. He told FOX 25 the Oklahoma County District Attorney’s office reached out to folks with Cindy Byrd’s office and was told the audit would cost $100,000, adding that she’s so swamped that she can’t do it this calendar year.

FOX 25 also reached out to Jason Lowe’s office but they said they have no comment.

Oklahoma

Oklahoma lawmakers vote to rename turnpike in honor of Toby Keith

OKLAHOMA CITY (KSWO) — Oklahoma lawmakers have voted to honor country music artist and Oklahoma native Toby Keith.

House Concurrent Resolution 1019 recognizes Keith’s lasting impact on music and proposes renaming a planned turnpike in his memory.

The concurrent resolution was authored by Rep. Jason Blair, R-Morgan, and Sen. Lisa Standridge, R-Norman.

The planned route will extend from Interstate 44 east to Interstate 35, then continue east and north to I-40 at the Kickapoo Turnpike.

Copyright 2026 KSWO. All rights reserved.

Oklahoma

What could happen if Oklahoma State Superintendent becomes an appointed position

Governor Kevin Stitt has said he wants the State Superintendent of Education to be a governor-elected position instead of an elected one. Political analyst Scott Mitchell examines what this would mean for the state.

Oklahoma Gov. Kevin Stitt is urging lawmakers to send a state question to voters that would make the state superintendent an appointed position, as he named Lindel Fields of Tulsa to the role and announced a turnaround team to help implement his education agenda.

Is the State Superintendent an elected role?

Yes, the State Superintendent of Education is still an elected role. Elections are scheduled for Nov. 3, 2026.

Cons of making the superintendent an appointed position

Mitchell said making this position appointed could cause distrust among some Oklahomans

“Over the years, we’ve seen that capture of regulatory sort of is easy to do when you have term limits, then lobbies become more powerful, and they have all the history. It’s very complicated.

He also said if the position were to be elected, they would likely have the same agenda as the governor.

“Yes, and I think the governor would be absolutely saying, ‘Yes, they’re going to do what I want them to do.’”

Changing how the superintendent is chosen changes what the founding fathers set.

“Voters are going to have to say yay or nay if it gets to them, is whether or not we want to change the way that the founding fathers set up the way that we make sure that power is not concentrated in Oklahoma,” he said.

Is Ryan Walters’ term the reason Stitt wants to make this position appointed?

Mitchell said he believes the former State Superintendent played a role in the government wanting to appoint this position.

During his time as superintendent, Walters was known to have multiple controversies. He resigned in 2025, allowing Stitt to appoint Lindel Fields.

“His impact on this, even though he’s gone, is certainly evident,” said Mitchell. “Walters left midstream, right? And so the governor had a chance to appoint someone. Well, it wasn’t just an appointment; it was chaos before and relative calm and competency after. And that has given the governor an opening for people to see with their own eyes. Yeah, you can put somebody in, we’re talking about Lindel Fields, that appears to get up every day, not trying to find some, get a click on social media, but rather to do his job. And across the board, for the most part, this guy’s getting thumbs up.

Stitt said electing Fields has already given him some leverage since he has been well perceived so far.

“That allows a governor to say, Look, I’ve got some standing, some leverage to go to the voters and say, let’s put expertise as the main reason that a person’s there, not because they were able to win an election because they had some sort of populist or dramatic ideas.”

Who is running for Oklahoma State Superintendent?

Republican Ballot

- Sen. Adam Pugh

- John Cox

- Rep. Toni Hasenbeck

- Ana Landsaw

Democrat Ballot

- Craig Mcvay

- Jennettie Marshall

Independent

To learn more about each candidate, click here.

A full breakdown of candidates in the 2026 Oklahoma State Superintendent race, including party affiliation, background and key education priorities.

-

World2 days ago

World2 days agoExclusive: DeepSeek withholds latest AI model from US chipmakers including Nvidia, sources say

-

Massachusetts3 days ago

Massachusetts3 days agoMother and daughter injured in Taunton house explosion

-

Montana1 week ago

Montana1 week ago2026 MHSA Montana Wrestling State Championship Brackets And Results – FloWrestling

-

Louisiana5 days ago

Louisiana5 days agoWildfire near Gum Swamp Road in Livingston Parish now under control; more than 200 acres burned

-

Denver, CO2 days ago

Denver, CO2 days ago10 acres charred, 5 injured in Thornton grass fire, evacuation orders lifted

-

Technology7 days ago

Technology7 days agoYouTube TV billing scam emails are hitting inboxes

-

Technology7 days ago

Technology7 days agoStellantis is in a crisis of its own making

-

Politics7 days ago

Politics7 days agoOpenAI didn’t contact police despite employees flagging mass shooter’s concerning chatbot interactions: REPORT