Inmate/students practice blues harmonica during a classroom session of the Blues Tradition in American Literature course inside Parchman Prison in Mississippi.

John Burnett

hide caption

toggle caption

John Burnett

Inmate/students practice blues harmonica during a classroom session of the Blues Tradition in American Literature course inside Parchman Prison in Mississippi.

John Burnett

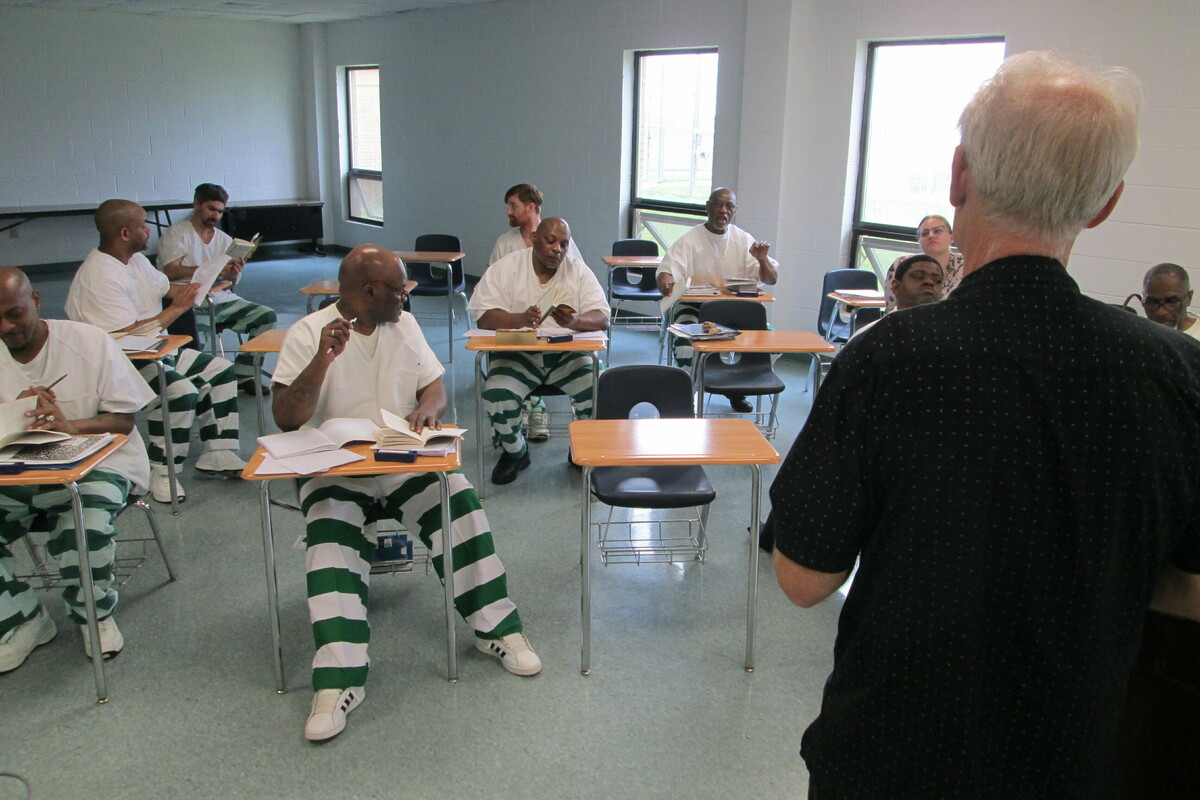

PARCHMAN, Miss. — Nine big men sit attentively at their desks inside the Mississippi State Penitentiary—the once infamous prison labor colony known as Parchman Farm. They’re wearing green-and-white striped pants, and shirts with “MDOC convict” stenciled on the back, for Mississippi Department of Corrections.

Their crimes range from drug possession to armed robbery to homicide. But inside this austere classroom, they’re all college students.

The course is The Blues Tradition in American Literature.

They’re exploring how the themes of blues lyrics—bad luck and trouble, sexual escapades, and euphoric freedom—get expressed in literary forms. They’re listening to blues songs by Big Joe Williams, Ma Rainey, Little Walter, Hound Dog Taylor, and Bessie Smith. They’re reading poetry from Langston Hughes and a play by August Wilson.

The feeling of the blues is all too familiar

For these inmate students, the course syllabus may be new but the feeling of the blues is all too familiar.

Professor Adam Gussow looks out the window of his classroom inside the sprawling Mississippi State Penitentiary, located on 28 square miles of the Mississippi Delta.

John Burnett

hide caption

toggle caption

John Burnett

Professor Adam Gussow looks out the window of his classroom inside the sprawling Mississippi State Penitentiary, located on 28 square miles of the Mississippi Delta.

John Burnett

“Of course, the blues is not just the music, but it’s also life lived hard,” says Adam Gussow, professor of English and Southern Studies at the University of Mississippi. He is 65, with a shock of white hair, an intense pedagogical manner, and a deep love for the blues. He’s taught this course for 25 years, usually to young undergraduates with limited life experiences. This is the first time he’s had a classroom full of grown men who live in confinement.

“I’ve taught them things about the music, per se, that they may not have known,” he says. “But they’ve taken that term and applied it to the life challenges they’ve had and the negativity they’ve dealt with.”

Ledale Williams, 46, hometown Vicksburg, Miss.: “I never looked at the blues the way I look at the blues now. This is trials and tribulations just being here for almost 29 years since I was a child. So that’s the blues in itself.”

Ledale Williams is taking the blues literature class at Parchman for three hours of college credit at the University of Mississippi. “Just being here for almost 29 years since I was a child,” he says, “that’s the blues in itself.”

John Burnett

hide caption

toggle caption

John Burnett

Mitchell Price, 55, Dallas: “My mother’s the daughter of a sharecropper and that’s what they did in the fields, they sung the blues. At the end of the rows, at break time, when they’re eating baloney and crackers and cheese. They were singin’ blues and somebody would play the harmonica. It’s part of my history because I used to hear my family talk about these things.”

Joseph Westbrooks, 63, Pontotoc, Miss.: “It’s more to it than listenin’ to the blues, when you live the blues. That’s our everyday life. You oppressed daily by being incarcerated.”

On this day, Prof. Gussow is teaching Zora Neale Hurston’s masterpiece, Their Eyes Were Watching God, about a Black woman’s turbulent coming of age in 1930s rural Florida. The protagonist, Janie, goes through three husbands. The last one is a rogue and a blues musician named Tea Cake.

“Tea Cake deepens Janie’s blues feelings,” Gussow lectures. “Tea Cake teaches Janie all about the blues in a particular way. He loves her and then he leaves her, and then he comes back. That’s an incredibly bluesy moment and I’m going to connect it with some music.”

Connecting life’s challenges to music

He opens his laptop and clicks on a link to Bumble Bee Blues, recorded by Memphis Minnie nearly a hundred years ago.

“Bumblebee, bumblebee, where you been so long?” she sings, to a haunting acoustic guitar, “You stung me this mornin’, I been restless all day long.”

Gussow exhorts his students: “This is a song about a man putting desire in a woman, right?” The men respond, “uh-huh,” in knowing voices.

“They’re just sayin’ that when he leave, she miss him,” says Christopher Bradley, 48, from Moss Point, Miss. “It’s like sayin, ‘Hey, I miss my baby. I be glad when she get home from work.’ “

Parchman Prison sprawls across 28 square miles of America’s musical bottomland. This is the Mississippi Delta. Beyond the tall fences and concertina wire, past the green crop fields now tilled by contract farmers, are the tiny agricultural towns that produced some of the greatest bluesmen who ever lived: B.B. King, Albert King, Muddy Waters, John Lee Hooker, Son House, and Robert Johnson.

Professor Adam Gussow has been teaching his blues literature course for 25 years, but never before inside a prison. “The blues is not just music,” he says, “but it’s also life lived hard.”

John Burnett

hide caption

toggle caption

John Burnett

Professor Adam Gussow has been teaching his blues literature course for 25 years, but never before inside a prison. “The blues is not just music,” he says, “but it’s also life lived hard.”

John Burnett

They knew to stay out of Parchman. Life in the prison farm was brutal. The institution was set up in 1901 as a huge, state-run plantation. Chain gangs did mandatory field work. Harsh discipline was meted out by the guards and by trusty convicts.

The Delta bluesman Bukka White served time for assault in Parchman and sang about it in his classic, Parchman Farm Blues, released in 1940.

We got to work in the mornin’, just at dawn of day,

We got to work in the mornin’, just at dawn of day,

Just at the settin’ of the sun, that’s when the work is done.

I’m down on ole Parchman farm, I sho’ wanna go back home,

I’m down on ole Parchman farm, I sho’ wanna go back home,

But I hope some day, I will overcome.

“The penitentiary here in Parchman was called camps for a reason,” says inmate Mitchell Price, who remembers those times. “They were work camps which you would say symbolizes slave camps. They put them here to pick cotton and they would whip them with actual whips.”

Melvin Johnson, 62, Jackson, Miss., was also doing time back in those days.

“About 5:30, you gotta be goin’ out there to that field,” he says. “Sometime it’s so cold out there they don’t care. All they want you to do is pick that cotton. You gon’ go out there or else. And sometime it so hot there you pass out. They didn’t care.”

Forced farm labor at Parchman ended in the mid-2000s. But problems persist.

Last year, the U.S. Justice Department released results of an investigation that “uncovered evidence of systemic violations that have generated a violent and unsafe environment for people incarcerated at Parchman.” A spokesman for the Mississippi Department of Corrections said that report does not reflect improved conditions at the prison in recent years. He pointed to accreditation in January by the American Correctional Association—the first time in nine years.

Using education to re-enter society

The University of Mississippi has offered college courses inside Parchman on Shakespeare, Mississippi writers, the civil rights movement, and now, the blues. The award-winning program is called the Prison-to-College Pipeline.

Patrick Alexander, associate professor of English and African American Studies at Ole Miss, is the program’s director and co-founder. He says education can play a role in how well an offender does when they re-enter society.

“We have one student who’s gone to Mississippi College,” Alexander says, “and he traces not just the assignments and the books but the opportunity to be seen as a leader [in the classroom]. Something that is not necessarily going to happen when you’re inside of Parchman.”

These students will don caps and gowns in mid-May and attend a graduation ceremony inside the prison for completing the three course hours.

The Hohner Company donated blues harmonicas to Professor Gussow’s students, but they can only practice once a week in class. They’re forbidden to take the harmonicas back to their living quarters.

John Burnett

hide caption

toggle caption

John Burnett

The Hohner Company donated blues harmonicas to Professor Gussow’s students, but they can only practice once a week in class. They’re forbidden to take the harmonicas back to their living quarters.

John Burnett

In addition to learning about the blues literary tradition, they get a taste of playing the blues. The students get harmonica lessons on Blues Harps donated by the Hohner Company. But they can’t take their mouth harps back to their living quarters so they have to practice in class. Gussow not only has a Ph.D. in English from Princeton, but he is a world-class harmonica player who teamed up with bluesman Sterling “Mr. Satan” Magee for more than three decades.

“I’m gonna tap my foot and I’m gonna take the four draw. Can everybody go…” …he plays a note and the students follow. He plays another note and the students follow. Pretty soon they’re tooting a primitive riff.

“All right, give yourselves a round of applause!” Gussow says with a laugh. “That’s the best we’ve done.”

A muscular man with a white goatee and glasses suddenly stands up out of his desk at the back of class. Arthur Gentry, 65, from Houston, has been locked up at Parchman for more than four decades. In a husky voice, he breaks into a spontaneous version of the Parchman Prison Blues, breathing new life and new pain into a venerable musical tradition.

I got the penitentiary blues,

day in and day out,

all through the night,

I got the blues,

we all got the blues.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25607996/0dfe32749d756e61.jpeg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25535555/STK160_X_TWITTER__B.jpg)