Mississippi

As the Mississippi Swerves, Can We Let Nature Regain Control?

Like most people during the pandemic, Alex Kolker found himself with extra time on his hands. A coastal geologist at the Louisiana Universities Marine Consortium, Kolker studies the Mississippi River Delta, and his work often involves surveying the watershed’s ever-changing wetlands and bays through the window of a small airplane. In 2021, with such research trips out of the question, Kolker did the next best thing — he conducted a flyover of the Delta on his computer screen, via satellite imagery. That was when he saw something peculiar.

At a location about 70 river miles south of downtown New Orleans, adjacent to the small shrimping community of Buras, Kolker zoomed in on a large breach between the Mississippi and Breton Sound, the shallow saltwater bay that shapes the top of Louisiana’s foot. The cut, called Neptune Pass, was wide — too wide for Kolker not to have recognized it before.

To preserve the shipping channel and protect communities and infrastructure from flooding, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers constantly dredges and maintains a more or less continuous levee system on both sides of the Mississippi throughout its Delta — except in the area of Neptune Pass. Here, where there is little human settlement and even less solid ground, the river’s east bank is relatively untouched. It’s also prone to breaching. Kolker wasn’t sure if Neptune Pass was a natural crevasse or manmade. But he knew that prior to 2019, it had been small — no wider than 150 feet.

“Can we create a solution that balances the restoration needs with the navigation needs?” a conservationist asks.

The Mississippi’s flow in 2019 had been exceptionally high due to record-setting precipitation, and Kolker surmised that the added water pressure likely contributed to the widening of Neptune Pass. When he was finally able to conduct an onsite survey of the crevasse last May, he discovered that it had expanded to 850 feet. And its depth, once no more than 20 feet, had plunged to between 40 and 80 feet. In one area, it reached 100 feet.

Such a wide and deep channel does not go unnoticed by the fourth-longest river in the world. Every hour, on average, the Mississippi discharges about 2.1 billion cubic feet of water into the Gulf of Mexico — the volume equivalent to 17 Superdomes, New Orleans’ professional football stadium. Kolker and his team calculated that some 118,000 cubic feet per second of water was being diverted through Neptune Pass — a rate five times greater than the discharge of the Hudson River into New York Harbor. “When we measured it, the Mississippi wasn’t even at its maximum, so it could probably get up to 150,000 [cubic feet],” says Kolker. The current volume of discharge, he adds, means “Neptune Pass is now one of the largest rivers [by volume] in the country.”

NASA / ESA / Yale Environment 360

Not long ago, the Corps would have treated Neptune Pass as a simple problem with a simple solution: It was a hole that needed to be sealed off. But in its many attempts over the last century to keep the Mississippi glued in place for flood control and navigation, the agency’s actions have rippled through the Delta and its ecosystems. Once-regular infusions of sediment-rich spillover from the Mississippi — which built and nourished the Delta – have been severed. With less sediment flushing into its wetlands, the Delta has broken down, and great swaths of it have been consumed by the rising Gulf. The land that is left is often too weak to survive hurricanes.

The Corps has “changed very little about how we manage and think about the river,” says Alisha Renfro, a coastal scientist with the National Wildlife Federation. “So we have a system that’s kind of on life support.” With Neptune Pass, scientists and environmentalists have been urging the Corps to think differently, to allow the river to run a little more freely. And this time, the agency appears to be listening.

If nothing is done to slow the loss of land in the Delta, an additional 2,250 square miles could vanish in the next 50 years.

In keeping with its “engineering with nature” ethos, which has been evolving over the past decade, the Corps is currently working on a plan that would allow Neptune Pass to stay open, albeit with a greatly diminished flow. “There’s a lot of pressure and enough changes happening in the river that the Corps is going to be pushed to think more about how to be innovative,” says Renfro. “Can we create a solution to Neptune Pass that balances the restoration needs of the area with the navigation needs? I don’t think it has to be one versus the other.”

A river’s flow, especially one as massive as the Mississippi’s, is hardly just water — mud, clay, sand, and silt are laced throughout the water column. When that flow washes into shallow bays or low-lying wetlands, those materials settle to the bottom, creating new deltas layer by layer. For the last 7,000 years, the Mississippi has carried the building blocks of earth south from 31 U.S. states and two Canadian provinces, shifting courses and building “delta lobes” — and the toe of Louisiana’s boot — across what is today Louisiana’s coast.

The 17th Street canal levee in New Orleans on August 29, 2010, the fifth anniversary of Hurricane Katrina.

Mario Tama / Getty Images

But beginning in the late 1700s, engineers and planners began hammering the lower Mississippi into a fixed course to both reduce flooding in the towns and cities sprouting along its banks and improve navigation for commercial vessels. At the time of the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927, the river already had 1,500 miles of levees. Following the 1928 Flood Control Act, the Army Corps took over management of the river, eventually adding another 2,000 miles of levees, along with other flood-control infrastructure. “The river is a dynamic system,” says Renfro. “It changes and shifts. And here we’ve held it in place and tried desperately to keep it there for a long time.”

Economically, this herculean effort has paid off: Today, the Mississippi supports an estimated $128 billion in annual commerce — from grain exports to oil and gas production to ecotourism. Much of this economy requires the Mississippi to remain in its current state. After all, what good is a petroleum or container terminal if it no longer sits beside the shipping channel? And allowing ships to exit the river through Neptune Pass would require a massive amount of dredging and new navigational infrastructure.

But environmentally, this control of the river has been a disaster. Starved of nourishment, the Delta’s lobes, which protect communities and industrial facilities from the full force of hurricane storm surges, have greatly subsided. And in recent decades, sea level rise has accelerated the collapse. According to the U.S. Geological Survey, since 1932, more than 2,000 square miles of land in the Mississippi Delta have disappeared under water.

Ship captains have reported that Neptune Pass had become so powerful it was pulling their vessels into its vortex.

If nothing is done to slow the loss, Louisiana’s Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority (CPRA) estimates that an additional 2,250 square miles could vanish over the next 50 years. To underscore the urgency of the situation, Simone Maloz, campaign director for Restore the Mississippi River Delta, a non-governmental organization that consults with the CPRA, points to 2021’s Hurricane Ida. “In that one storm alone, we lost 100 square miles,” she says. “Immediately, our landscape changed.”

Which was another reason Kolker was so interested in Neptune Pass. Yes, the crevasse was diverting an extraordinary volume of water from the Mississippi’s main stem, but it was also delivering enough sediment to form teardrop-shape sandbars in Quarantine and Denesse bays — part of the much larger Breton Sound, which has experienced significant land loss over the past century. Kolker estimates that while some of this new land came from Neptune Pass’s swallowed banks, at least 30 percent of it was coming from the Mississippi’s regular sediment flow, which, prior to the pass’s opening, was being lost to the depths of the Gulf beyond the river’s multi-pronged mouth. In other words, Neptune was performing exactly as a natural diversion should: It was building land.

Maloz points to efforts by her group and others to “reconnect” the river to the vast areas of the Delta from which it has been blocked off. “We have got to use the fresh water and sediment that’s available in the Mississippi right now — that’s the key to long-term sustainability,” she says, adding that Neptune Pass “is a perfect example of what we’re talking about when we talk about reconnecting the river.”

Neptune Pass in 2017 and 2022.

Google Earth / Yale Environment 360

While the Army Corps has evolved in terms of working with nature instead of against it — its engineers now use sand, silt, and mud dredged from the shipping channel to build up eroded wetlands, for example — it still considers Neptune Pass to be a menace. Like Alex Kolker, the agency had also begun watching the crevasse in 2021, noting that it was diverting enough water to alter the Mississippi’s current and create shoals of sediment just below the pass. “When you start to see enough water being pulled off, and enough of a drop in velocity that sediment is falling out, that’s when you know there’s going to be significant impact” on shipping, says Ricky Boyett, the chief of public affairs for the Corps’ New Orleans District. For the first time ever, the agency had to dredge that section of the river last year.

Boyett says captains were reporting that Neptune Pass had become so powerful it was pulling their vessels into its vortex. The Corps then examined the riverbed around the start of the crevasse, discovering a thin clay lens sitting atop a thick sand layer. They worried that if the clay, which acts as a cap on the sand, were to wash out, the sand would quickly follow, triggering a massive expansion of Neptune Pass and a dramatic shift in the shipping channel. In 2022, the agency had to dredge shoals that had developed in the shipping channel as a result of the river’s altered flow, as well as install “emergency rock” on both sides of the crevasse’s entrance to prevent further widening. Then they published a plan for a “stone closure structure” within the pass that included a 100-foot notch at its center to “allow sediment, water, aquatic species, and small vessels to pass through.”

A home in Grand Isle, Louisiana, where land is disappearing underwater.

Drew Angerer / Getty Images

While integrating even a small notch would have been considered innovative thinking for the Corps a quarter century ago, it was too small a step for those who advocated for unleashing — at least somewhat — the Mississippi. “We were, like, ‘Hold your horses: Is there not anything that you can do right now that’s not permanent?’” says Maloz, who notes that she understands the need for safe navigation and supported the installation of emergency rock.

Rebecca Triche, executive director of the Louisiana Wildlife Federation, urged the Corps to allow scientists to collect more data on Neptune Pass’s land-building potential. “Without more robust scientific analysis and increased transparency to include stakeholders,” Trishe wrote to the agency, “decisions made today for a single issue could result in perpetual problems.”

While Boyett says the Corps is set on bringing Neptune Pass’ “size and volume back to what they were pre-2019,” he adds that, “if there’s a way we can design the closure in a way that still lets some sediment go through, then we’ll do that.” To that end, the Corps has taken extra time this summer to incorporate the kind of science and stakeholder input that Trishe requested. “We needed to go back to reevaluate the proposed design,” Boyett says. “We’re doing more modeling, getting more data, then we’ll kind of reevaluate and redo the designs.”

If it is left alone long enough, Neptune Pass could rewrite the course of the Mississippi River’s final miles.

One of the most significant tests of a more holistic approach to managing the Mississippi began on Aug. 10, when Louisiana’s CPRA broke ground on the Mid-Barataria Sediment Diversion, a 1,600-foot-wide, two-mile-long corridor that will be located about 35 miles downriver of New Orleans and carry sediment-rich water into Barataria Bay. “It’ll bring life back to the Barataria basin, which is a very stagnant, desolated system that has some pretty high wetland loss,” says Rudy Simoneaux, CPRA’s chief engineer.

It is not lost on anyone that the Mid-Barataria’s maximum allowed flow — 75,000 cubic feet per second — will be much less than that of another sediment diversion 36 river miles south, which was created naturally and free of charge: Neptune Pass. But the reality is that Neptune Pass is simply too good of a diversion. If left unchecked, it could very well take over most of the Mississippi’s flow and, if left alone long enough, rewrite the course of its final miles. This, of course, is what the Mississippi wants — and the Delta needs. Nevertheless, it is an impossible scenario for a river system that no longer shapes the human landscape but is itself shaped by it.

Up against this intractable dilemma, environmentalists say sediment diversion projects like Mid-Barataria offer significant hope for the Delta. “The lesson that we can apply today, that we didn’t have back in 1927 or before, is this idea of control,” Maloz says. “How do you balance the needs of folks who are making a living off the natural resources — like shrimpers and oystermen and fishermen — with vulnerable communities that desperately need storm protection? Control and balance are things that we talk about the most and what we know more about than we ever have before. But there’s still a long way to go.”

Mississippi

Southeast Mississippi Christmas Parades 2024 | WKRG.com

MISSISSIPPI (WKRG) — It’s beginning to look a lot like Christmas on the Gulf Coast and that means Santa Claus will be heading to town for multiple parades around the area.

WKRG has compiled a list of Christmas parades coming to Southeast Mississippi.

Christmas on the Water — Biloxi

- Dec. 7

- 6 p.m.

- Begins at Biloxi Lighthouse and will go past the Golden Nugget

Lucedale Christmas Parade

Mississippi

‘A Magical Mississippi Christmas’ lights up the Mississippi Aquarium

GULFPORT, Miss. (WLOX) – The Mississippi Aquarium in Gulfport is spreading holiday cheer with a new event, ‘’A Magical Mississippi Christmas.’

The aquarium held a preview Tuesday night.

‘A Magical Mississippi Christmas’ includes a special dolphin presentation, diving elves, and photos with Santa.

The event also includes “A Penguin’s Christmas Wish,” which is a projection map show that follows a penguin through Christmas adventures across Mississippi.

“It’s a really fun event and it’s the first time we really opened up the aquarium at night for the general public, so it’s a chance to come in and see what it’s like in the evening because it’s really spectacular and really beautiful,” said Kurt Allen, Mississippi Aquarium President and CEO.

‘A Magical Mississippi Christmas’ runs from November 29 to December 31.

It will not be open on December 11th, December 24th, and December 25th.

Tickets can be purchased online or at the gate.

The event is made possible by the city of Gulfport and Coca-Cola Bottling Company.

See a spelling or grammar error in this story? Report it to our team HERE.

Copyright 2024 WLOX. All rights reserved.

Mississippi

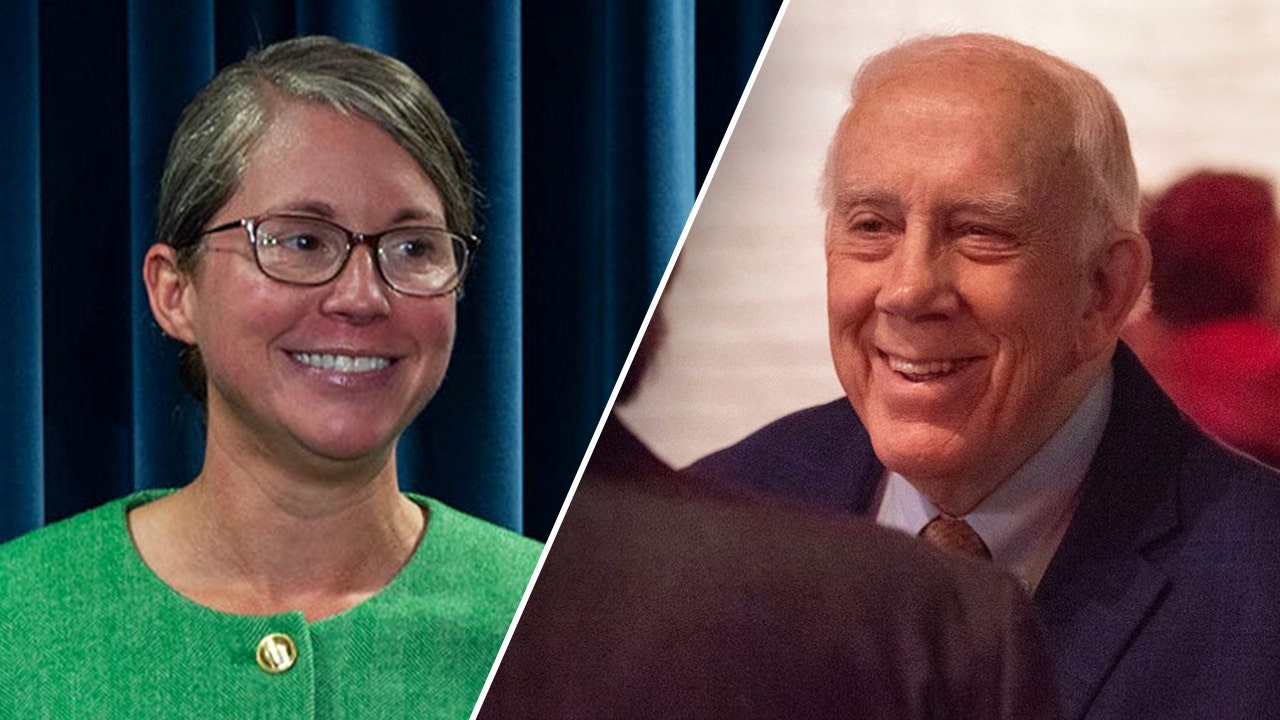

Mississippi asks for execution date of man convicted in 1993 killing, lawyers plan to appeal case to SCOTUS

Mississippi Attorney General Lynn Fitch, a Republican, is seeking an execution date for a convicted killer who has been on death row for 30 years, but his lawyer argues that the request is premature since the man plans to appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court.

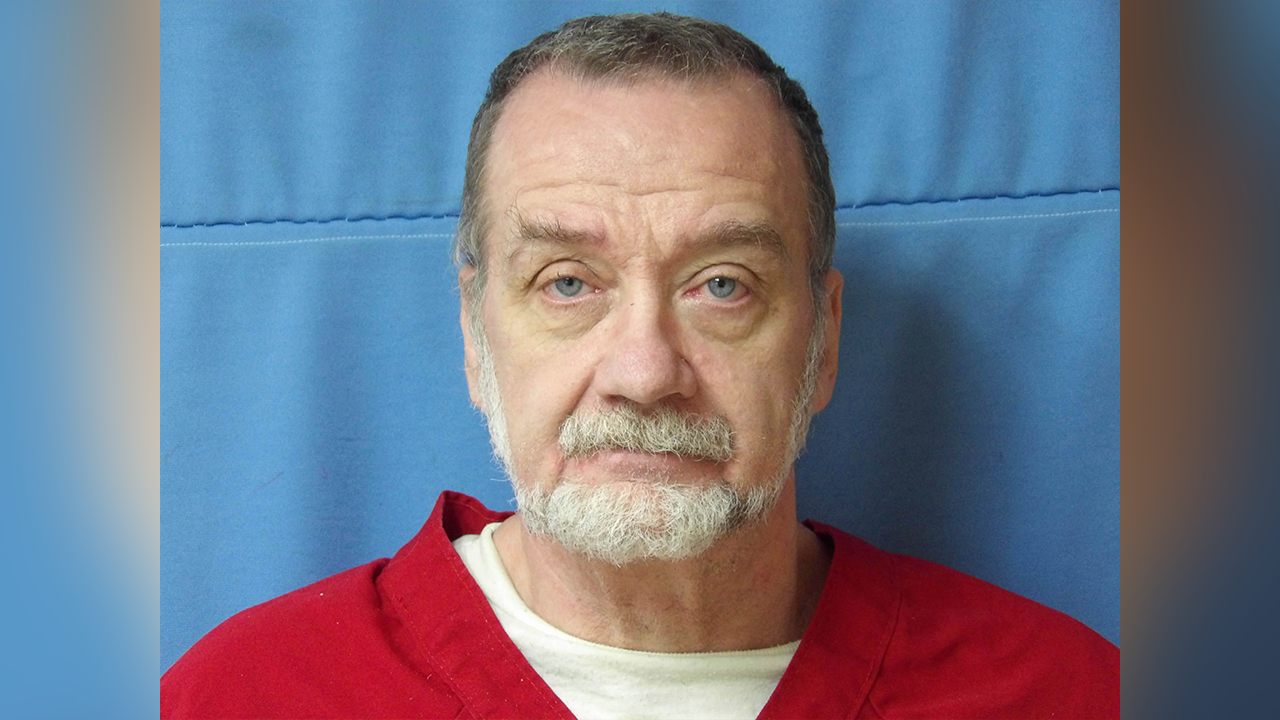

Charles Ray Crawford, 58, was sentenced to death in connection with the 1993 kidnapping and killing of 20-year-old community college student Kristy Ray, according to The Associated Press.

During his 1994 trial, jurors pointed to a past rape conviction as an aggravating circumstance when they issued Crawford’s sentence, but his attorneys said Monday that they are appealing that conviction to the Supreme Court after a lower court ruled against them last week.

Crawford was arrested the day after Ray was kidnapped from her parents’ home and stabbed to death in Tippah County. Crawford told officers he had blacked out and did not remember killing her.

TEXAS LAWMAKER PROPOSES BILL TO ABOLISH DEATH PENALTY IN LONE STAR STATE: ‘I THINK SENTIMENT IS CHANGING’

Mississippi death row inmate Charles Ray Crawford, who was convicted and sentenced to death in 1994 in the 1993 kidnapping and killing of a community college student, 20-year-old Kristy Ray. (Mississippi Department of Corrections via AP)

He was arrested just days before his scheduled trial on a charge of assaulting another woman by hitting her over the head with a hammer.

The trial for the assault charge was delayed several months before he was convicted. In a separate trial, Crawford was found guilty in the rape of a 17-year-old girl who was friends with the victim of the hammer attack. The victims were at the same place during the attacks.

Crawford said he also blacked out during those incidents and did not remember committing the hammer assault or the rape.

During the sentencing portion of Crawford’s capital murder trial in Ray’s death, jurors found the rape conviction to be an “aggravating circumstance” and gave him the death sentence, according to court records.

PRO-TRUMP PRISON WARDEN ASKS BIDEN TO COMMUTE ALL DEATH SENTENCES BEFORE LEAVING

During the sentencing portion of Crawford’s capital murder trial, jurors found his prior rape conviction to be an “aggravating circumstance” and gave him the death sentence. (iStock)

In his latest federal appeal of the rape case, Crawford claimed his previous lawyers provided unconstitutionally ineffective assistance for an insanity defense. He received a mental evaluation at the state hospital, but the trial judge repeatedly refused to allow a psychiatrist or other mental health professional outside the state’s expert to help in Crawford’s defense, court records show.

On Friday, a majority of the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals rejected Crawford’s appeal.

But the dissenting judges wrote that he received an “inadequately prepared and presented insanity defense” and that “it took years for a qualified physician to conduct a full evaluation of Crawford.” The dissenting judges quoted Dr. Siddhartha Nadkarni, a neurologist who examined Crawford.

“Charles was laboring under such a defect of reason from his seizure disorder that he did not understand the nature and quality of his acts at the time of the crime,” Nadkarni wrote. “He is a severely brain-injured man (corroborated both by history and his neurological examination) who was essentially not present in any useful sense due to epileptic fits at the time of the crime.”

Photo shows the gurney of an execution chamber. (AP Photo/Sue Ogrocki, File)

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

Crawford’s case has already been appealed multiple times using various arguments, which is common in death penalty cases.

Hours after the federal appeals court denied Crawford’s latest appeal, Fitch filed documents urging the state Supreme Court to set a date for Crawford’s execution by lethal injection, claiming that “he has exhausted all state and federal remedies.”

However, the attorneys representing Crawford in the Mississippi Office of Post-Conviction Counsel filed documents on Monday stating that they plan to ask the U.S. Supreme Court to overturn the appeals court’s ruling.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.

-

Science1 week ago

Science1 week agoTrump nominates Dr. Oz to head Medicare and Medicaid and help take on 'illness industrial complex'

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoTrump taps FCC member Brendan Carr to lead agency: 'Warrior for Free Speech'

-

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25739950/247386_Elon_Musk_Open_AI_CVirginia.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25739950/247386_Elon_Musk_Open_AI_CVirginia.jpg) Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoInside Elon Musk’s messy breakup with OpenAI

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoProtesters in Slovakia rally against Robert Fico’s populist government

-

Health5 days ago

Health5 days agoHoliday gatherings can lead to stress eating: Try these 5 tips to control it

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoThey disagree about a lot, but these singers figure out how to stay in harmony

-

Health2 days ago

Health2 days agoCheekyMD Offers Needle-Free GLP-1s | Woman's World

-

Science2 days ago

Science2 days agoDespite warnings from bird flu experts, it's business as usual in California dairy country