Florida

A DeSantis Speech Too Dangerous to Teach in Florida

Florida Governor Ron DeSantis does not often find himself attempting to deliver a unifying message, but in the aftermath of the killing of three Black Floridians by an alleged white supremacist in Jacksonville last week, he tried.

“What he did is totally unacceptable in the state of Florida,” DeSantis said during a speech at a vigil for the three victims, A.J. Laguerre, Angela Michelle Carr, and Jerrald Gallion, last Sunday. “We are not going to let people be targeted based on their race.”

That’s a welcome message, but it didn’t go over well. The Associated Press reported that DeSantis “was loudly booed” as he addressed the vigil. Among the potential reasons is that DeSantis has spent much of his time in office cracking down on “wokeness,” to the delight of his conservative fans. The state has passed laws censoring classroom instruction that might lead students to conclude that racial discrimination, against Black Americans in particular, persists into the present, even as it engages in such discrimination in broad daylight.

One of those laws is the Stop WOKE Act, which prohibits any instruction that, as the Miami Herald reported, “could prompt students to feel discomfort about a historical event because of their race, ethnicity, sex or national origin.” In fact, one could argue that Florida law now prohibits DeSantis’s speech itself from being discussed in Florida schools.

Jacksonville Sheriff T. K. Waters was clear that the shooter was a “madman” who “hated Blacks, and I think he hated just about everyone that wasn’t white.” The gunman was also the latest white supremacist to leave behind a manifesto, which the police have not released.

If Florida teachers allowed their students to read DeSantis’s speech, they might ask about the motive for the attack. A teacher who explained that the shooter was motivated by white-supremacist hatred would risk making a white student feel discomfort, “guilt, anguish, or other forms of psychological distress,” as the law itself puts it. If the teacher tried to put the speech in context, and attempted to explain the ideological tenets, origins, and history of white supremacy in the United States, they would increase that risk. A teacher could not explain why someone would, as DeSantis put it, target people “based on their race,” because it would lead to answers about the history of Florida and America that the governor and other Republicans would prefer students not learn, lest they have nonconservative thoughts.

The teacher could not mention that Florida had one of the highest rates of lynching per capita during the Jim Crow era, more than 300 such killings from 1877 to 1950. They could not discuss that the purpose of such killings was to terrorize Black Floridians into accepting segregation and subjugation. They would be unable to mention Harry T. Moore, Willie James Howard, or the Newberry Six. Under the law, teachers who did so could end up in conversations that would put them at risk of losing their teaching certificate. After all, discussing such subjects might hurt someone’s feelings. In short, the safest thing would be not to discuss the speech at all.

That a Florida governor might have made it illegal for an educator to explain the context of his own speech may sound ridiculous, but these are legal considerations that educators have to take into account when laws ban certain ideas from being discussed. Such prohibitions have a chilling effect, and most institutions are risk-averse when it comes to litigation. Indeed, that is the idea behind these gag measures, to chill left-wing or “woke” speech about topics such as racial discrimination, gender, and sexual orientation. There’s no explicit exception for “when the governor wants to try to be magnanimous in the aftermath of a racist massacre” in the text of the law.

If this still seems improbable, the Herald has already documented similarly absurd exchanges over the state’s curriculum. The report illustrates how state officials objected to the idea that enslaved people “had no wages to pass down to descendants, no legal right to accumulate property, and individual exceptions depended on their enslavers’ whims,” because it might be “promoting the critical race theory idea of reparations.” Primary source documents from Black antislavery activists were described as including “content prohibited under Florida law.” They worried that a unit on the abolitionist movement was not “factually inclusive or balanced”; a “nonwoke” curriculum, I suppose, places antislavery and proslavery principles on the same moral plane. Officials also complained that material explaining that the growth of the Black middle class was hampered by mid-century discrimination ran afoul of state rules, because “it failed to offer other reasons outside of systemic racism and discrimination for the wealth disparity between Black Americans and other racial groups.”

These education gag laws are intended to render the American past illegible, because of the risk that someone might reach the conclusion that racial discrimination continues to be a problem in the present that Americans are obliged to confront. They make education impossible by censoring the historical record in favor of the political conclusions their authors want students to draw. They make it illegal to teach facts if conservatives find those facts offensive.

It is a small irony that these laws also arguably bar teachers from talking about a speech in which DeSantis was trying to condemn racial discrimination rather than hide it behind a veil of superficial patriotism. For those who argue that the law was not intended to do this, well, an entire academic discipline explores how laws written one way can be enforced in another. I won’t bring it up here, though, because it’s illegal to teach in the “free state” of Florida.

Florida

Man who allegedly defrauded CT victim of $100K+ extradited from Florida

A Florida man was arrested for allegedly defrauding a victim in Connecticut of over $100,000, police said.

On Thursday, Coventry police arrested 29-year-old Osmaldy De La Rosa Nunez of Orlando, Florida, on one count of first-degree larceny after an investigation into a wire fraud in August 2022, according to the department.

Police alleged that De La Rosa Nunez communicated with the victim as a person with whom the victim was familiar and had money transferred to him that was due to a third party which amounted to a loss of around $135,000.

According to police, De La Rosa Nunez was using a fictitious name, and his true identity was discovered with the assistance of the Florida Department of Law Enforcement.

De La Rosa Nunez was held in Florida as a fugitive from justice, police said. He waived extradition and was transported back to Connecticut to face charges.

De La Rosa Nunez was being held on a $500,000 court-set bond and was scheduled to be arraigned at Rockville Superior Court on Friday.

Florida

Why doesn’t Florida have vehicle inspections?

ORLANDO, Fla. – News 6 traffic safety expert Trooper Steve Montiero answers viewer questions about the rules of the road every week, helping Florida residents become better drivers by being better educated.

Trooper Steve on Thursday was asked, “Why doesn’t Florida have vehicle inspections?”

[EXCLUSIVE: Become a News 6 Insider (it’s FREE) | PINIT! Share your photos]

Florida has not had vehicle inspections, unlike several northern states, for quite some time, Trooper Steve said.

“In the early ‘80s, Gov. Bob Graham ended vehicle inspections. About 10 years later, they were reinstated until 2001 when Gov. Jeb Bush stopped them due to costs,” Trooper Steve said.

Florida does not require annual vehicle inspections, but there are some laws on the books that allow law-enforcement to keep smoky vehicles off the road, he added.

Florida Statute 316.272 (2) says, “The engine and power mechanism of every motor vehicle shall be so equipped and adjusted as to prevent the escape of excessive fumes or smoke.”

And Florida Statute 316.2935 discusses air pollution control equipment.

If you have a question for Trooper Steve, submit it here.

For more Ask Trooper Steve content, click or tap here.

Copyright 2024 by WKMG ClickOrlando – All rights reserved.

Florida

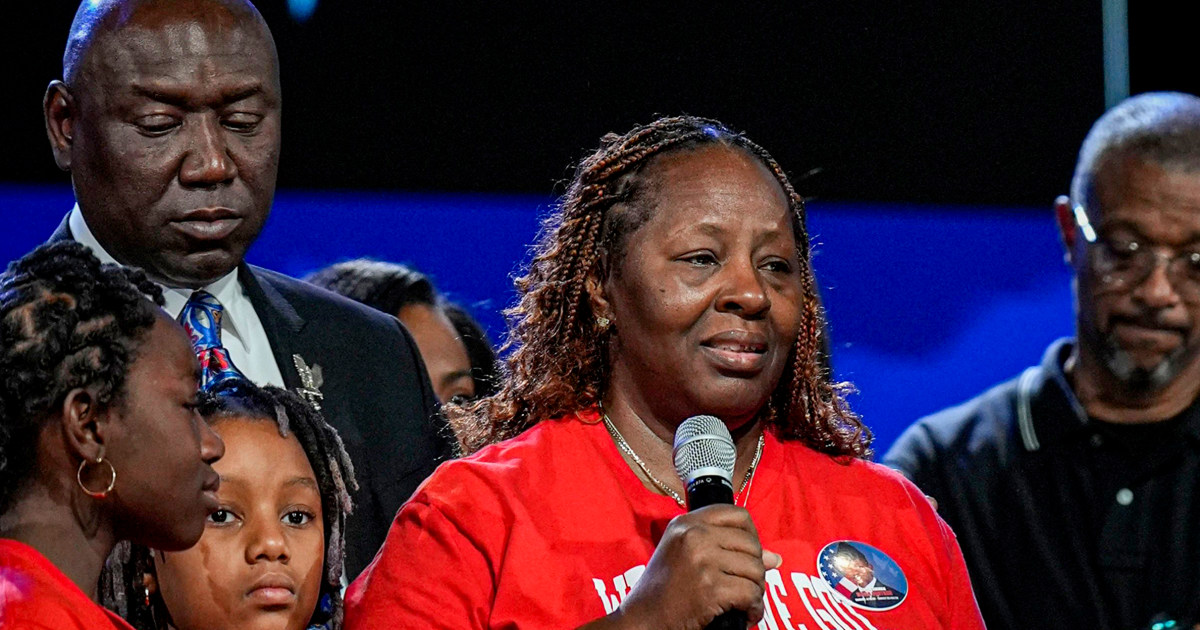

Florida deputy's killing of Black airman renews debate on police killings and race

WASHINGTON (AP) — In 2020, the top enlisted leader of the Air Force went public with his fear of waking up to the news that a Black airman had been killed by a white police officer.

Then four years later, a Florida deputy shot and killed Senior Airman Roger Fortson in his apartment.

“I doubt if that police officer knew or cared that Roger was an airman. What he saw was a young, Black male,” retired Chief Master Sgt. Kaleth O. Wright said in an interview Wednesday with The Associated Press.

After George Floyd was killed by a white Minneapolis police officer in May 2020, Wright, who like Floyd is Black, felt compelled to speak publicly about the fears that he and his younger troops had. It didn’t seem to matter how hard he’d worked to serve his country. There were still police who would only see him as a threat.

The national outcry surrounding Floyd’s death pushed Wright to lead some initiatives to better address racial issues within the Air Force. But by his own account, they didn’t go far enough. Fortson’s death has left him wondering if things will ever change.

“Right now, in the midst of what happened to Roger, it’s kind of a big deal. People are talking about it, the Air Force is dealing with it. But in a couple of weeks, it will go away, right?” Wright said.

The investigation into Fortson’s death is ongoing, and the sheriff’s office has not released the name or race of the officer involved.

On Wednesday, Okaloosa County Sheriff Eric Aden went to Hurlburt Field where Fortson served and met with Lt. Gen. Tony Bauernfeind, the head of Air Force Special Operations Command, to talk about the next steps.

Sabu Williams, president of the Okaloosa County NAACP branch, was there and said he did not leave with a sense that the sheriff’s office thought Fortson’s race was a factor in the shooting.

But “bias certainly played a role in this thing,” Williams said. “From my perspective, we feel we don’t get the benefit of the doubt. It seems to be a ‘shoot first, ask questions later’ kind of thing.”

In a statement posted to his Facebook page late Wednesday, Bauernfeind said the meeting with the sheriff’s office was productive and that the command would host a town hall in the coming days to talk further about the shooting and the way forward.

There is no government-managed national data collection system that tracks fatalities caused by law enforcement officers. The FBI has a database, but it’s voluntary, and less than two-thirds of local, state, tribal and federal agencies provided data for it last year. In any case, there is no breakdown by race.

Databases kept by private organizations, however, have found that fatal police encounters have risen each year since Floyd was killed and those killings are disproportionately of Black people.

Two databases, one by The Washington Post and another compiled by Campaign Zero, run by academics and activists advocating for police accountability, found that while more white people are killed in police encounters overall, Black people are disproportionately killed by police. Black people make up about 12% of the U.S. population but account for about a quarter of police killings in each of the databases.

In the meeting at Hurlburt, Williams requested that the sheriff’s office pursue de-escalation training and unconscious bias training, which he said the sheriff supported.

The sheriff’s office said in a statement posted on Facebook that they have received the local NAACP’s “list of demands and understand their concerns.” In the meeting at the airfield, the sheriff “emphasized his commitment to do what is right,” it said.

Michael P. Heiskell, the president of the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers, said the deputy’s race doesn’t matter when determining whether unconscious bias played a role.

“Whatever the race of this deputy, whether he’s Black, white, Hispanic, whatever — in this instance where this deputy saw a Black person with a weapon and immediately used deadly force, instead of calmly and reflectively assessing the situation, this is it.”

Williams’ NAACP chapter is drafting state legislation it wants to name after Fortson. The bill would require police to use de-escalating language before using force if they encounter someone with a gun who is not being held in a threatening position.

Released police body camera footage shows Fortson had his gun in his hand when he opened his front door, but the barrel was pointed to the floor. Within seconds the deputy shot him, only afterward telling him to drop the weapon.

“A little bit of de-escalation or discussion” by the deputy could have given the airman the chance to put down the gun, Williams said. “He wasn’t given any time.”

MaCharie Dunbar, a board member of the Black Veterans Project, a national organization created to address racial inequality in the experiences of Black service members, said he wonders whether it would have made a difference if Fortson had been in uniform.

“One thing proven true time and again is that if you’re Black in America, it doesn’t matter what kind of job you have, the clothes you wear, the car you drive, the house you live in,” said Dunbar, who is retired from the Air Force and had been stationed at Hurlburt Field. “At the end of the day, you’re just Black. And there are some who hold on to this ideology that Black people are dangerous.”

Fortson’s shooting occurred against a wider backdrop of increased attention by the military to racial issues in its ranks. Over the past few years, internal reviews have found significant disparities in opportunities for promotion and uneven military punishments.

But there has been significant pushback against those efforts, with far-right members of Congress criticizing them as being “woke.” Congress this year put caps on what the Pentagon can pay experts in promoting diversity, equity and inclusion.

Wright said that pushback has served to silence much discussion on the issue and, for now, the most helpful thing commanders can do is listen.

“If you’re a white male officer in the United States Air Force, you don’t wake up every day thinking about race,” Wright said. “We have Black airmen and officers that wake up every day and they go into rooms and they’re the only Black person.”

He said commanders need to understand the toll this takes.

“It comes with stress and anxiety. It comes with a feeling of not belonging. And, you know, most of us are taught to just assimilate, right? You know, don’t complain, don’t be the outcast. Don’t be the outsider because, you know, sometimes you get labeled as an angry Black man.”

If airmen don’t feel like they’re supported in their own units, it’s unlikely they will trust opening up to commanders on an issue as big as Fortson’s shooting, he said.

Wright is now thinking about writing another column, and maybe getting involved on the issue again. But he’s not sure what needs to be done to prevent a future incident. Bringing the sheriff’s deputies on base to help them see Black airmen differently won’t fix the problem without a larger, societal change, he said. Asking commanders to have the equivalent of “the talk” with Black airmen that parents have with their Black children about encounters with the police isn’t a solution either.

“I don’t know that commanders could say anything to airmen that would necessarily be helpful about, ‘if the police knock on your door, do this, don’t do that,’ ” Wright said. “Young African American males, they know the drill, right? They already know the story. And, still, it’s not enough.”

Wright has two sons, ages 22 and 27. His heart has been breaking for Fortson’s mother, who buries her 23-year-old son on Friday.

“That could have easily been one of my sons,” Wright said.

___

Lauer reported from Philadelphia. Aaron Morrison in New York City contributed to this report.

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week ago'You need to stop': Gov. Noem lashes out during heated interview over book anecdote about killing dog

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoMan, 75, confesses to killing wife in hospital because he couldn’t afford her care, court documents say

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoBiden takes role as bystander on border and campus protests, surrenders the bully pulpit

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoRFK Jr said a worm ate part of his brain and died in his head

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoPentagon chief confirms US pause on weapons shipment to Israel

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoHere's what GOP rebels want from Johnson amid threats to oust him from speakership

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoPro-Palestine protests: How some universities reached deals with students

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoConvicted MEP's expense claims must be published: EU court

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24401979/STK071_ACastro_apple_0002.jpg)