Science

Mosquito season is upon us. So why are Southern California officials releasing more of them?

Jennifer Castellon shook, tapped and blew on a box to shoo out more than 1,000 mosquitoes in a quiet, upscale Inland Empire neighborhood.

The insects had a job to do, and the pest scientist wanted every last one out.

Aggressive and impactful reporting on climate change, the environment, health and science.

Their task? Find lady mosquitoes and mate.

But these were no ordinary mosquitoes. Technicians had zapped the insects, all males, with radiation in a nearby lab to make them sterile. If they achieve their amorous quest, there will be fewer baby mosquitoes than there would be if nature ran its course. That means fewer mouths to feed — mouths that thirst for human blood.

“I believe, fingers crossed, that we can drop the population size,” said Solomon Birhanie, scientific director for the West Valley Mosquito and Vector Control District, which released the mosquitoes in several San Bernardino County neighborhoods this month.

Sterilized male Aedes mosquitoes are released from a box in Rancho Cucamonga.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

Controlling mosquitoes with mosquitoes

Mosquito control agencies in Southern California are desperate to tamp down an invasive mosquito — called Aedes aegypti — that has exploded in recent years. Itchy, unhappy residents are demanding it. And the mosquitoes known for fierce ankle biting aren’t just putting a damper on outdoor hangouts — they also spread disease.

The low-flying, day-biting mosquitoes can lay eggs in tiny water sources. A bottle cap is fair game. And they might lay a few, say, in a plant tray and others, perhaps, in a drain. Tackling the invaders isn’t easy when it can be hard to even locate all the reproduction spots. So public health agencies increasingly are trying to use the insects’ own biology against them by releasing sterilized males.

The West Valley district, which covers six cities in San Bernardino County, rolled out the first program of this kind in California last year. Now they’re expanding it. Next month, a vector district covering a large swath of Los Angeles County will launch its own pilot, followed by Orange County in the near future. Other districts are considering using the sterile insect technique, as the method is known, or watching early adopters closely.

On the plus side, it’s an approach that doesn’t rely on pesticides, which mosquitoes become resistant to, but it requires significant resources and triggers conspiracy theories.

“People are complaining that they can’t go into their backyard or barbecue in the summer,” Birhanie said at his Ontario lab. “So we needed something to strengthen our Aedes control.” Of particular concern is the Aedes aegypti, which love to bite people — often multiple times in rapid succession.

Releasing sterilized male insects to combat pests is a proven scientific technique, but using it to control invasive mosquitoes is relatively new.

Vector control experts often point to the success of a decades-long effort in California to fight Mediterranean fruit flies by dropping enormous quantities of sterile males from small planes. That program, run by the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the California Department of Food and Agriculture, costs about $16 million a year. That’s nearly four times West Valley’s annual budget.

So rather than try to tackle every nook and cranny of the district, encompassing roughly 650,000 residents, West Valley decided to use a more targeted approach. If a problem area reaches a certain threshold — over 50 mosquitoes counted in an overnight trap — it becomes a candidate.

1

2

3

4

5

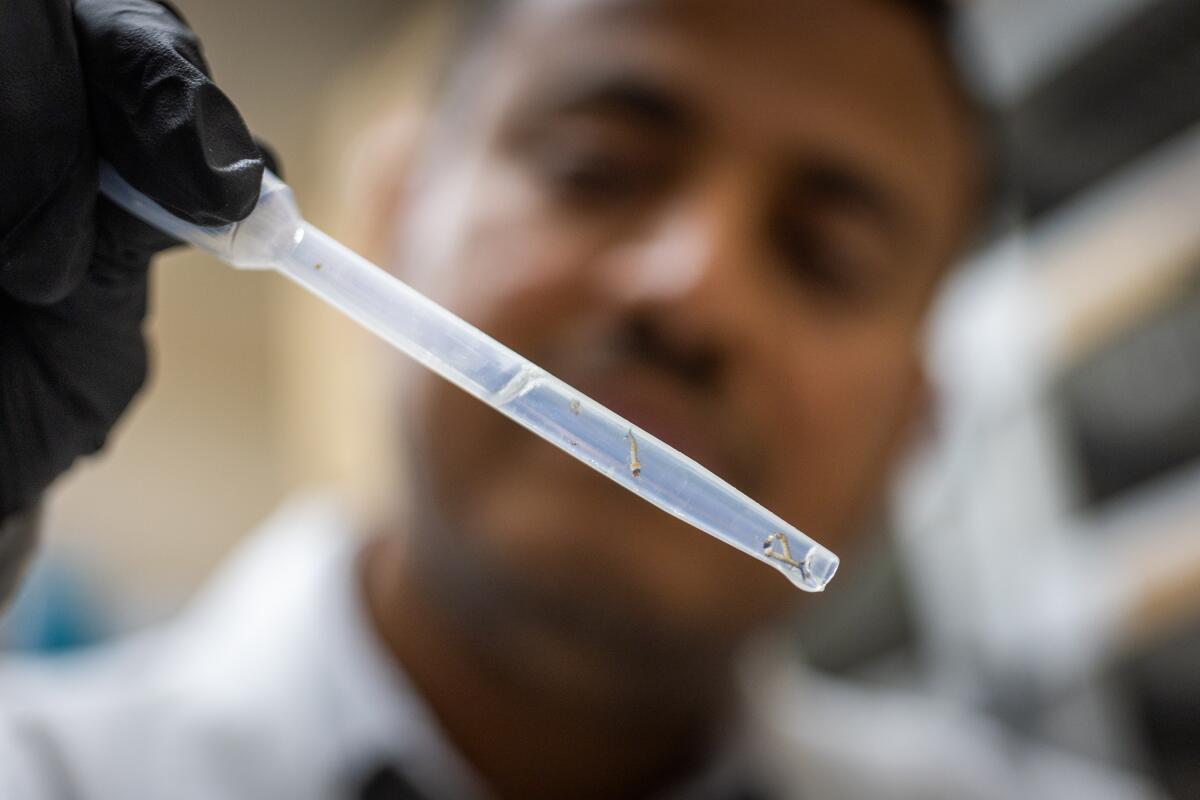

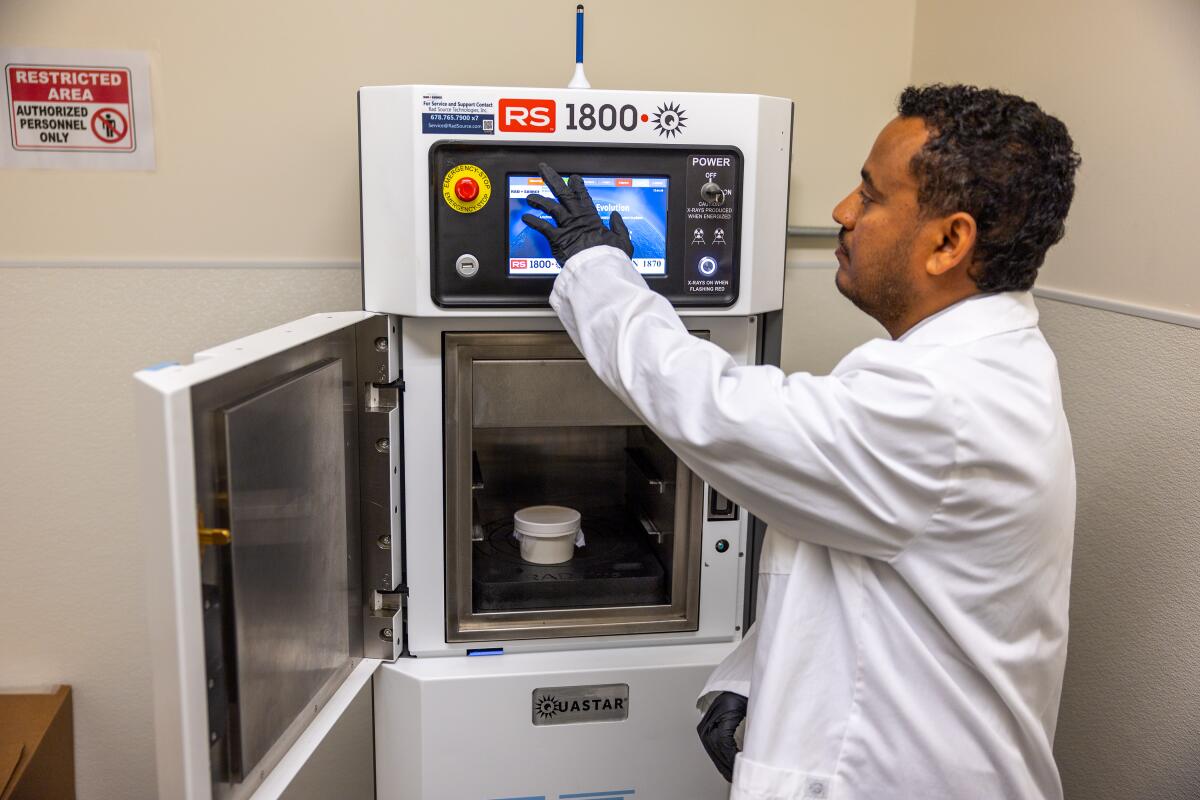

1. Solomon Birhanie inspects a container of mosquito larvae in the lab at the West Valley Mosquito and Vector Control District in Ontario. 2. Birhanie and his team raise mosquitoes in the lab, separating them by sex, because only the males, which don’t bite humans, will eventually be released. 3. Mosquito eggs in the West Valley lab. 4. The lab can grow about 10,000 mosquitoes at a time. 5. Before the male mosquitoes are released, an X-ray machine sterilizes them. If the zapped males mate with a female, her eggs won’t hatch. (Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

And it’s still a big lift. About 10,000 mosquitoes are reared at a time at West Valley’s facility, about half of which will be males. The males are separated out, packed into cups and placed into an X-ray machine that looks like a small refrigerator. The sterilizing process isn’t that different from microwaving a frozen dinner. Zap them on a particular setting for four to five minutes and they’re good to go.

Equipment purchased for the program costs roughly $200,000, said Brian Reisinger, spokesperson for the district. He said it was too early to pin down a cost estimate for the program, which is expanding.

Some districts serving more people are going bigger.

The Greater Los Angeles County Vector Control District plans to unleash up to 60,000 mosquitoes a week in two neighborhoods in Sunland-Tujunga from mid-May through November.

With the sterile-insect program, “the biggest hurdle we’re up against really is scalability,” said Susanne Kluh, general manager of the L.A. County district, which is responsible for nearly 6 million residents across 36 cities.

In part to save money, Kluh’s district has partnered with the Orange County Mosquito and Vector Control District. They’re sharing equipment and collaborating on studies, but L.A. County’s releases will move forward first, said Brian Brannon, spokesperson for the O.C. district. Orange County expects to release its “ankle biter fighters,” as Brannon called them, in Mission Viejo this fall or next spring.

So far, the L.A. County district has shelled out about $255,000 for its pilot, while O.C. has spent around $160,000. It’s a relatively small portion of their annual budgets: L.A. at nearly $25 million and O.C. at $17 million. But the area they’re targeting is modest.

Mosquito control experts tout sterilization for being environmentally friendly because it doesn’t involve spraying chemicals, and it may have a longer-lasting effectiveness than pesticides. It can also be done now. Other methods involving genetically modified mosquitoes and ones infected with bacteria are stuck in an approval process that spans federal and state agencies. One technique, involving the bacteria Wolbachia was recently approved by the Environmental Protection Agency and is now heading to the California Department of Pesticide Regulation to review, said Jeremy Wittie, general manager for the Coachella Valley Mosquito and Vector Control District.

“Using pesticides or insecticides, resistance crops up very quickly,” said Nathan Grubaugh, associate professor of epidemiology at the Yale School of Public Health.

Vector control experts hope the fact that the sterilization technique doesn’t involve genetic modification will tamp down conspiracy theories that have cropped up around mosquito releases. One erroneous claim is that a Bill Gates-backed effort to release mosquitoes was tied to malaria cases in Florida and Texas. Reputable outlets debunked the conspiracy theory, pointing out that Gates’ foundation didn’t fund the Florida project and that the type of mosquito released (Aedes) does not transmit malaria.

To get ahead of concerns, districts carrying out the releases say they’ve engaged in extensive outreach and education campaigns. Residents’ desire to rid themselves of a scourge may overcome any anxieties.

“I think if you have the choice of getting eaten alive by ankle biters or having a DayGlo male X-rayed mosquito come by looking for a female to not have babies with, you’d probably go for the latter,” Brannon said. (“DayGlo” is a riff on the fluorescent pigment product of the same name — the sterilized mosquitoes were dusted with bright colors to help identify them.)

Sterilized male mosquitoes buzz around vector ecologist Jennifer Castellon as they are released in Rancho Cucamonga earlier this month.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

Disease at our doorstep

As the climate warms and some regions become wetter, dengue is expanding to areas it’s never been seen before — and surging in areas where it’s established. Florida has seen alarming spikes in the viral infection in recent years, and Brazil and Puerto Rico are currently battling severe outbreaks. While most people infected with dengue have no symptoms, it can cause severe body aches and fever and, in rare cases, death. Its alias, “breakbone fever,” provides a grim glimpse into what it can feel like.

In October of last year, the city of Pasadena announced the Golden State’s first documented locally transmitted case of dengue, describing it as “extremely rare” in a news release. That same month, a second case was confirmed in Long Beach. Local transmission means the patient hadn’t traveled to a region where dengue is common; they may have been bitten by a mosquito carrying the disease in their own neighborhood.

Surging dengue abroad means there’s more opportunity for travelers to bring it home. However, Grubaugh said it doesn’t seem that California is imminently poised for a “Florida-like situation,” where there were nearly 1,000 cases in 2022, including 60 that were locally acquired. Southern California in particular lacks heavy rainfall that mosquitoes like, he said. But some vector experts believe more locally acquired cases are inevitable.

Ale Macias releases sterilized male mosquitoes in Upland this month.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

Set them free

In mid-April, a caravan of staffers from the West Valley district traveled to five mosquito “hot spots” in Chino, Upland and Rancho Cucamonga — where data showed mosquito levels were particularly high — to release their first batches of sterilized male mosquitoes for the year. Peak Aedes season is months away, typically August to October in the district, and Birhanie said that’s the point. The goal is to force down the numbers to prevent an itchy tsunami later.

Males don’t bite, so the releases won’t lead to more inflamed welts. But residents might notice more insects in the air. Sterilized males released by West Valley will outnumber females in the wild by at least 100 to 1 to increase their chances of beating out unaltered males, spokeperson Reisinger said.

“They’re not going to be contributing to the biting pressure; they’re just going to be looking for love,” as Reisinger put it.

Eggs produced by a female after a romp with a sterile male don’t hatch. And female mosquitoes typically mate only once, meaning all her eggs are spoiled, so to speak. Vector experts say the process drives down the population over time.

Interestingly, the hot spots were fairly spread out across the district, indicative of the bloodsuckers’ widespread presence and adaptive nature. A picturesque foothills community in Upland was “especially interesting” because of its relatively high elevation, Birhanie said.

It was once inhabited primarily by another invasive mosquito that prefers colder, mountainous climates. Construction and deforestation in the area has literally paved the way for its humidity- and heat-loving brethren to move in.

Another neighborhood, in Rancho Cucamonga, posed a mystery. For the last two years, mosquito levels were consistently high. Door-to-door inspections, confoundingly, didn’t reveal the source.

“That’s one of the things about invasive Aedes mosquitoes — you can’t find them,” he said.

Next steps

Some vector control experts want to see a regional approach to sterile mosquito releases, similar to the state Medfly program.

Jason Farned, district manager for the San Gabriel Valley Mosquito and Vector Control District, believes a widespread effort “would be much more effective” and thinks that will come in time.

There are no talks underway to make it happen, and it’s not yet clear how it would work. Vector control agencies are set up to serve their local communities.

Fears of a bad mosquito year ahead are bubbling as the weather warms. Rain — which there was plenty of this spring — can quickly transform into real estate for mosquito reproduction.

When the swarms come, mosquito haters can take typical precautions: dump standing water and wear repellent. And they can root for the sterile males to get lucky.

Science

Owners of fire-destroyed Palisades mobile home park seek to displace residents for development deal

For months, former residents of the Pacific Palisades Bowl Mobile Estates have feared the uncommunicative owners of the property would seek to displace them in favor of a more lucrative development deal after the Palisades fire destroyed the rent-controlled, roughly 170-unit mobile home park.

A confidential memorandum listing the Bowl for sale indicates the owners intend to do exactly that.

The memorandum, quietly posted on a website associated with the global commercial real estate company CBRE, says that the Palisades fire created a “blank canvas for redevelopment” at a site “ideally positioned for a transformative residential or mixed-use project.”

“I just thought, oh my god, this is so much propaganda and false advertising,” said Lisa Ross, a 33-year resident of the Bowl and a Realtor. “How can they even get away with printing this?”

Neither the current owners of the Bowl nor the real estate companies listed on the memorandum responded to requests for comment.

The memorandum describes the current single-family residential zoning as “favorable” for developers; however, the city and mobile housing law experts have painted a different picture.

Fire debris at Pacific Palisades Bowl in January 2026.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

“Multifamily and mixed-use development on this site is not allowed by existing zoning and land use regulations,” Mayor Karen Bass’s office said in a statement Wednesday, adding only low density single-family housing or reconstructing the mobile home park are currently allowed. “Mayor Bass will continue taking action and [work] with residents to restore the Palisades community.”

City Councilmember Traci Park also reiterated her focus on getting the mobile home park rebuilt and allowing residents to return, with a spokesperson noting she is not entertaining the potential for any rezoning efforts from a developer.

Zoning changes typically require a city council vote and are subject to the mayor’s approval or veto.

Beyond the zoning laws, the site is also currently governed by a state law requiring cities to preserve affordable housing along the coast and a city ordinance protecting mobile home residents against sudden displacement.

Spencer Pratt, a resident of the Palisades and an outspoken supporter of the neighborhood’s mobile home community, criticized the mayor and the owners in a statement to The Times. “It’s unfortunate that Karen Bass has not advocated for mobile home residents impacted by the fire,” he said, “and that the current owner of the Bowl is ignoring good faith offers from residents to buy the property.”

The mayor’s office disputed this, noting Bass recently led a delegation of Palisadians, including mobile home owners, to Sacramento to advocate for recovery. “Mayor Bass’ priority is getting every Palisadian home — single-family homeowners, town home owners, renters, mobile home owners.”

Los Angeles Mayor Karen Bass speaks during a private ceremony outside City Hall with faith leaders, LAPD officers and city officials to commemorate the one-year anniversary of the Eaton and Palisades fires on Jan. 7, 2026.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

Bass also advocated for the federal government to include the Bowl in its debris cleanup efforts; however, the Federal Emergency Management Agency ultimately refused to include it, unlike other mobile home parks impacted by the Palisades fire. Its reasoning: It could not trust the owners to rebuild the park as affordable housing.

Court rulings over the years found the owners routinely failed to maintain the infrastructure and worked to replace the park with an “upscale resort community.” Residents also accused the owners of attempting to circumvent rent control regulations.

After the fire, it ultimately took more than 13 months to begin cleaning up the debris.

Ross said she approached the owners with independent mobile home park developers who were interested in buying the fire-destroyed lot and letting residents rebuild within months. She also approached the owners with a proposition that the former residents band together to buy the park. She heard nothing back.

“They don’t communicate,” Ross said. “It’s a feuding family. That’s also why we had so many problems with maintenance and with upgrades in the park.”

Pratt, who is running for mayor against Bass, also called on private developers like Rick Caruso to step in and save the Bowl. (Caruso’s team noted his rebuilding nonprofit is looking into how to help residents of the Bowl.)

Ross is a fan of Pratt’s proposition. “We need those kinds of people — we need Rick Caruso. That would be great,” Ross said. To sweeten the deal: “I’ll cook for him. I would make him all his favorite dishes.”

Science

A virus without a vaccine or treatment is hitting California. What you need to know

A respiratory virus that doesn’t have a vaccine or a specific treatment regimen is spreading in some parts of California — but there’s no need to sound the alarm just yet, public health officials say.

A majority of Northern California communities have seen high concentrations of human metapneumovirus, or HMPV, detected in their wastewater, according to data from the WastewaterScan Dashboard, a public database that monitors sewage to track the presence of infectious diseases.

A Los Angeles Times data analysis found the communities of Merced in the San Joaquin Valley, and Novato and Sunnyvale in the San Francisco Bay Area have seen increases in HMPV levels in their wastewater between mid-December and the end of February.

HMPV has also been detected in L.A. County, though at levels considered low to moderate at this point, data show.

While HMPV may not necessarily ring a bell, it isn’t a new virus. Its typical pattern of seasonal spread was upended by the COVID-19 pandemic, and its resurgence could signal a return to a more typical pre-coronavirus respiratory disease landscape.

Here’s what you need to know.

What is HMPV?

HMPV was first detected in 2001, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. It’s transmitted by close contact with someone who is infected or by touching a contaminated surface, said Dr. Neha Nanda, chief of infectious diseases and hospital epidemiologist for Keck Medicine of USC.

Like other respiratory illnesses, such as influenza, HMPV spreads and is more durable in colder temperatures, infectious-disease experts say.

Human metapneumovirus cases commonly start showing up in January before peaking in March or April and then tailing off in June, said Dr. Jessica August, chief of infectious diseases at Kaiser Permanente Santa Rosa.

However, as was the case with many respiratory viruses, COVID disrupted that seasonal trend.

Why are we talking about HMPV now?

Before the pandemic hit in 2020, Americans were regularly exposed to seasonal viruses like HMPV and developed a degree of natural immunity, August said.

That protection waned during the pandemic, as people stayed home or kept their distance from others. So when people resumed normal activities, they were more vulnerable to the virus. Unlike other viruses, there isn’t a vaccine for human metapneumovirus.

“That’s why after the pandemic we saw record-breaking childhood viral illnesses because we lacked the usual immunity that we had, just from lack of exposure,” August said. “All of that also led to longer viral seasons, more severe illness. But all of these things have settled down in many respects.”

In 2024, the national test positivity for HMPV peaked at 11.7% at the end of March, according to the National Respiratory and Enteric Virus Surveillance System. The following year’s peak was 7.15% in late April.

So far this year, the highest test positivity rate documented was 6.1%, reported on Feb. 21 — the most recent date for which complete data are available.

While the seasonal spread of viruses like HMPV is nothing new, people became more aware of infectious diseases and how to prevent them during the pandemic, and they’ve remained part of the public consciousness in the years since, August and Nanda said.

What are the symptoms of HMPV?

Most people won’t go to the doctor if they have HMPV because it typically causes mild, cold-like symptoms that include cough, fever, nasal congestion and sore throat.

HMPV infection can progress to:

- An asthma attack and reactive airway disease (wheezing and difficulty breathing)

- Middle ear infections behind the ear drum

- Croup, also known as “barking” cough — an infection of the vocal cords, windpipe and sometimes the larger airways in the lungs

- Bronchitis

- Fever

Anyone can contract human metapneumovirus, but those who are immunocompromised or have other underlying medical conditions are at particular risk of developing severe disease — including pneumonia. Young children and older adults are also considered higher-risk groups, Nanda said.

What is the treatment for HMPV?

There is no specified treatment protocol or antiviral medication for HMPV. However, it’s common for an infection to clear up on its own and treatment is mostly geared toward soothing symptoms, according to the American Lung Assn.

A doctor will likely send you home and tell you to rest and drink plenty of fluids, Nanda said.

If symptoms worsen, experts say you should contact your healthcare provider.

How to avoid contracting HMPV

Infectious-disease experts said the best way to avoid contracting HMPV is similar to preventing other respiratory illnesses.

The American Lung Assn.’s recommendations include:

- Wash your hands often with soap and water. If that’s not available, clean your hands with an alcohol-based hand sanitizer.

- Clean frequently touched surfaces.

- Crack open a window to improve air flow in crowded spaces.

- Avoid being around sick people if you can.

- Avoid touching your eyes, nose and mouth.

Assistant data and graphics editor Vanessa Martínez contributed to this report.

Science

After rash of overdose deaths, L.A. banned sales of kratom. Some say they lost lifeline for pain and opioid withdrawal

Nearly four months ago, Los Angeles County banned the sale of kratom, as well as 7-OH, the synthetic version of the alkaloid that is its active ingredient. The idea was to put an end to what at the time seemed like a rash of overdose deaths related to the drug.

It’s too soon to tell whether kratom-related deaths have dissipated as a result — or, really, whether there was ever actually an epidemic to begin with. But many L.A. residents had become reliant on kratom as something of a panacea for debilitating pain and opioid withdrawal symptoms, and the new rules have made it harder for them to find what they say has been a lifesaving drug.

Robert Wallace started using kratom a few years ago for his knees. For decades he had been in pain, which he says stems from his days as a physical education teacher for the Glendale Unified School District between 1989 and 1998, when he and his students primarily exercised on asphalt.

In 2004, he had arthroscopic surgery on his right knee, followed by varicose vein surgery on both legs. Over the next couple of decades, he saw pain-management specialists regularly. But the primary outcome was a growing dependence on opioid-based painkillers. “I found myself seeking doctors who would prescribe it,” he said.

He leaned on opioids when he could get them and alcohol when he couldn’t, resulting in a strain on his marriage.

When Wallace was scheduled for his first knee replacement in 2021 (he had his other knee replaced a few years later), his brother recommended he take kratom for the post-surgery pain.

It seemed to work: Wallace said he takes a quarter of a teaspoon of powdered kratom twice a day, and it lets him take charge of managing his pain without prescription painkillers and eases harsh opiate-withdrawal symptoms.

He’s one of many Angelenos frustrated by recent efforts by the county health department to limit access to the drug. “Kratom has impacted my life in only positive ways,” Wallace told The Times.

For now, Wallace is still able to get his kratom powder, called Red Bali, by ordering from a company in Florida.

However, advocates say that the county crackdown on kratom could significantly affect the ability of many Angelenos to access what they say is an affordable, safer alternative to prescription painkillers.

Kratom comes from the leaves of a tree native to Southeast Asia called Mitragyna speciosa. It has been used for hundreds of years to treat chronic pain, coughing and diarrhea as well as to boost energy — in low doses, kratom appears to act as a stimulant, though in higher doses, it can have effects more like opioids.

Though advocates note that kratom has been used in the U.S. for more than 50 years for all sorts of health applications, there is limited research that suggests kratom could have therapeutic value, and there is no scientific consensus.

Then there’s 7-OH, or 7-Hydroxymitragynine, a synthetic alkaloid derived from kratom that has similar effects and has been on the U.S. market for only about three years. However, because of its ability to bind to opioid receptors in the body, it has a higher potential for abuse than kratom.

Public health officials and advocates are divided on kratom. Some say it should be heavily regulated — and 7-OH banned altogether — while others say both should be accessible, as long as there are age limitations and proper labeling, such as with alcohol or cannabis.

In the U.S., kratom and 7-OH can be found in all sorts of forms, including powder, capsules and liquids — though it depends on exactly where you are in the country. Though the Food and Drug Administration has recommended that 7-OH be included as a Schedule 1 controlled substance under the Controlled Substances Act, that hasn’t been made official. And the plant itself remains unscheduled on the federal level.

That has left states, counties and cities to decide how to regulate the substances.

California failed to approve an Assembly bill in 2024 that would have required kratom products to be registered with the state, have labeling and warnings, and be prohibited from being sold to anyone younger than 21.

It would also have banned products containing synthetic versions of kratom alkaloids. The state Legislature is now considering another bill that basically does the same without banning 7-OH — while also limiting the amount of synthetic alkaloids in kratom and 7-OH products sold in the state.

“Until kratom and its pharmacologically active key ingredients mitragynine and 7-OH are approved for use, they will remain classified as adulterants in drugs, dietary supplements and foods,” a California Department of Public Health spokesperson previously told The Times.

On Tuesday, California Gov. Gavin Newsom announced that the state’s efforts to crack down on kratom products has resulted in the removal of more than 3,300 kratom and 7-OH products from retail stores. According to a news release from the governor’s office, there has been a 95% compliance rate from businesses in removing the products.

(Los Angeles Times photo illustration; source photos by Getty Images)

Newsom has equated these actions to the state’s efforts in 2024 to quash the sale of hemp products containing cannabinoids such as THC. Under emergency state regulations two years ago, California banned these specific hemp products and agents with the state Department of Alcoholic Beverage Control seized thousands of products statewide.

Since the beginning of 2026, there have been no reported violations of the ban on sales of such products.

“We’ve shown with illegal hemp products that when the state sets clear expectations and partners with businesses, compliance follows,” Newsom said in a statement. “This effort builds on that model — education first, enforcement where necessary — to protect Californians.”

Despite the state’s actions, the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors is still considering whether to regulate kratom, or ban it altogether.

The county Public Health Department’s decision to ban the sale of kratom didn’t come out of nowhere. As Maral Farsi, deputy director of the California Department of Public Health, noted during a Feb. 18 state Senate hearing, the agency “identified 362 kratom-related overdose deaths in California between 2019 and 2023, with a steady increase from 38 in 2019 up to 92 in 2023.”

However, some experts say those numbers aren’t as clear-cut as they seem.

For example, a Los Angeles Times investigation found that in a number of recent L.A. County deaths that were initially thought to be caused by kratom or 7-OH, there wasn’t enough evidence to say those drugs alone caused the deaths; it might be the case that the danger is in mixing them with other substances.

Meanwhile, the actual application of this new policy seems to be piecemeal at best.

The county Public Health Department told The Times it conducted 2,696 kratom-related inspections between Nov. 10 and Jan. 27, and found 352 locations selling kratom products. The health department said the majority stopped selling kratom after those inspections; there were nine locations that ignored the warnings, and in those cases, inspectors impounded their kratom products.

But the reality is that people who need kratom will buy it on the black market, drive far enough so they get to where it’s sold legally or, like Wallace, order it online from a different state.

For now, retailers who sell kratom products are simply carrying on until they’re investigated by county health inspectors.

Ari Agalopol, a decorated pianist and piano teacher, saw her performances and classes abruptly come to a halt in 2012 after a car accident resulted in severe spinal and knee injuries.

“I tried my best to do traditional acupuncture, physical therapy and hydrocortisone shots in my spine and everything,” she said. “Finally, after nothing was working, I relegated myself to being a pain-management patient.”

She was prescribed oxycodone, and while on the medication, battled depression, anhedonia and suicidal ideation. She felt as though she were in a fog when taking oxycodone, and when it ran out, ”the pain would rear its ugly head.” Agalopol struggled to get out of bed daily and could manage teaching only five students a week.

Then, looking for alternatives to opioids, she found a Reddit thread in which people were talking up the benefits of kratom.

“I was kind of hesitant at first because there’re so many horror stories about 7-OH, but then I researched and I realized that the natural plant is not the same as 7-OH,” she said.

She went to a local shop, Authentic Kratom in Woodland Hills, and spoke to a sales associate who helped her decide which of the 47 strains of kratom it sold would best suit her needs.

Agalopol currently takes a 75-milligram dose of mitragynine, the primary alkaloid in kratom, when necessary. It has enabled her to get back to where she was before her injury: teaching 40 students a week and performing every weekend.

Agalopol believes the county hasn’t done its homework on kratom. “They’re just taking these actions because of public pressure, and public pressure is happening because of ignorance,” she said.

During the course of reporting this story, Authentic Kratom has shut down its three locations; it’s unclear if the closures are temporary. The owner of the business declined to comment on the matter.

When she heard the news of the recent closures, Agalopol was seething. She told The Times she has enough capsules of kratom for now, but when she runs out, her option will have to be Tylenol and ibuprofen, “which will slowly kill my liver.”

“Prohibition is not a public health strategy,” said Jackie Subeck, executive director of 7-Hope Alliance, a nonprofit that promotes safe and responsible access to 7-OH for consumers, at the Feb. 18 Senate hearing. “[It’s] only going to make things worse, likely resulting in an entirely new health crisis for Californians.”

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoExclusive: DeepSeek withholds latest AI model from US chipmakers including Nvidia, sources say

-

Wisconsin4 days ago

Wisconsin4 days agoSetting sail on iceboats across a frozen lake in Wisconsin

-

Massachusetts1 week ago

Massachusetts1 week agoMother and daughter injured in Taunton house explosion

-

Maryland5 days ago

Maryland5 days agoAM showers Sunday in Maryland

-

Massachusetts3 days ago

Massachusetts3 days agoMassachusetts man awaits word from family in Iran after attacks

-

Florida5 days ago

Florida5 days agoFlorida man rescued after being stuck in shoulder-deep mud for days

-

Denver, CO1 week ago

Denver, CO1 week ago10 acres charred, 5 injured in Thornton grass fire, evacuation orders lifted

-

Oregon7 days ago

Oregon7 days ago2026 OSAA Oregon Wrestling State Championship Results And Brackets – FloWrestling