Science

As the Great Salt Lake Dries Up, Utah Faces ‘An Environmental Nuclear Bomb’

SALT LAKE CITY — If the Great Salt Lake, which has already shrunk by two-thirds, continues to dry up, here’s what’s in store:

The lake’s flies and brine shrimp would die off — scientists warn it could start as soon as this summer — threatening the 10 million migratory birds that stop at the lake annually to feed on the tiny creatures. Ski conditions at the resorts above Salt Lake City, a vital source of revenue, would deteriorate. The lucrative extraction of magnesium and other minerals from the lake could stop.

Most alarming, the air surrounding Salt Lake City would occasionally turn poisonous. The lake bed contains high levels of arsenic and as more of it becomes exposed, wind storms carry that arsenic into the lungs of nearby residents, who make up three-quarters of Utah’s population.

“We have this potential environmental nuclear bomb that’s going to go off if we don’t take some pretty dramatic action,” said Joel Ferry, a Republican state lawmaker and rancher who lives on the north side of the lake.

As climate change continues to cause record-breaking drought, there are no easy solutions. Saving the Great Salt Lake would require letting more snowmelt from the mountains flow to the lake, which means less water for residents and farmers. That would threaten the region’s breakneck population growth and high-value agriculture — something state leaders seem reluctant to do.

Utah’s dilemma raises a core question as the country heats up: How quickly are Americans willing to adapt to the effects of climate change, even as those effects become urgent, obvious, and potentially catastrophic?

The stakes are alarmingly high, according to Timothy D. Hawkes, a Republican lawmaker who wants more aggressive action. Otherwise, he said, the Great Salt Lake risks the same fate as California’s Owens Lake, which went dry decades ago, producing the worst levels of dust pollution in the United States and helping to turn the nearby community into a veritable ghost town.

“It’s not just fear-mongering,” he said of the lake vanishing. “It can actually happen.”

A modern oasis, under threat

Say you climbed into a car at the edge of the Pacific and started driving east, tracing a line across the middle of the United States. After crossing the Klamath and Cascade mountains in Northern California, green and lush, you would reach the Great Basin Desert of Nevada and western Utah. In one of the driest parts of America, the landscape is a brown so pale, it’s almost gray.

But keep going east, and just shy of Wyoming you would find a modern oasis: a narrow strip of green, stretching some 100 miles from north to south, home to an uninterrupted metropolis beneath snow-capped mountains, sheltered under maple and pear trees. At the edge of that oasis, between the city and the desert, is the Great Salt Lake.

Utahns call that metropolis the Wasatch Front, after the 12,000-foot Wasatch Range above it. Extending roughly from Provo in the south to Brigham City in the north, with Salt Lake City at its center, it’s one of the fastest-growing urban areas in America — home to 2.5 million people, drawn by the natural beauty and relatively modest cost of living.

That megacity is possible because of a minor hydrological miracle. Snow that falls in the mountains just east of Salt Lake City feeds three rivers — the Jordan, Weber, and Bear — which provide water for the cities and towns of the Wasatch Front, as well as the rich cropland nearby, before flowing into the Great Salt Lake.

Until recently, that hydrological system existed in a delicate balance. In summer, evaporation would cause the lake to drop about two feet; in spring, as the snowpack melted, the rivers would replenish it.

Now two changes are throwing that system out of balance. One is explosive population growth, diverting more water from those rivers before they reach the lake.

The other shift is climate change, according to Robert Gillies, a professor at Utah State University and Utah’s state climatologist. Higher temperatures cause more snowpack to transform to water vapor, which then escapes into the atmosphere, rather than turning to liquid and running into rivers. More heat also means greater demand for water for lawns or crops, further reducing the amount that reaches the lake.

And a shrinking lake means less snow. As storms pass over the Great Salt Lake, they absorb some of its moisture, which then falls as snow in the mountains. A vanishing lake endangers that pattern.

“If you don’t have water,” Dr. Gillies said, “you don’t have industry, you don’t have agriculture, you don’t have life.”

‘At the precipice’

Last summer, the water level in the Great Salt Lake reached its lowest point on record, and it’s likely to fall further this year. The lake’s surface area, which covered about 3,300 square miles in the late 1980s, has since shrunk to less than 1,000, according to the U.S. Geological Survey.

The salt content in the part of the lake closest to Salt Lake City used to fluctuate between 9 percent and 12 percent, according to Bonnie Baxter, a biology professor at Westminster College. But as the water in the lake drops, its salt content has increased. If it reaches 17 percent — something Dr. Baxter says will happen this summer — the algae in the water will struggle, threatening the brine shrimp that consume it.

While the ecosystem hasn’t collapsed yet, Dr. Baxter said, “we’re at the precipice. It’s terrifying.”

The long term risks are even worse. One morning in March, Kevin Perry, a professor of atmospheric sciences at the University of Utah, walked out onto land that used to be underwater. He picked at the earth, the color of dried mud, like a beach whose tide went out and never came back.

The soil contains arsenic, antimony, copper, zirconium and other dangerous heavy metals, much of it residue from mining activity in the region. Most of the exposed soil is still protected by a hard crust. But as wind erodes the crust over time, those contaminants become airborne.

Clouds of dust also make it difficult for people to breathe, particularly those with asthma or other respiratory ailments. Dr. Perry pointed to shards of crust that had come apart, lying on the sand like broken china.

“This is a disaster,” Dr. Perry said. “And the consequences for the ecosystem are absolutely, insanely bad.”

Running out of water, but growing fast

In theory, the fix is simple: Let more water from melting snowpack reach the lake, by sending less toward homes, businesses and farms.

But metropolitan Salt Lake City has barely enough water to support its current population. And it is expected to grow almost 50 percent by 2060.

Laura Briefer, director of Salt Lake City’s public utilities department, said the city can increase its water supply in three ways: Divert more water from rivers and streams, recycle more wastewater, or draw more groundwater from wells. Each of those strategies reduces the amount of water that reaches the lake. But without those steps, demand for water in Salt Lake City would exceed supply around 2040, Ms. Briefer said.

The city is trying to conserve water. Last December, it stopped issuing permits for businesses that require significant water, such as data centers or bottling plants.

But city leaders have shied away from another potentially powerful tool: higher prices.

Of major U.S. cities, Salt Lake has among the lowest per-gallon water rates, according to a 2017 federal report. It also consumes more water for residential use than other desert cities — 96 gallons per person per day last year, compared with 78 in Tucson and 77 in Los Angeles.

Charge more for water and people use less, said Zachary Frankel, executive director of the Utah Rivers Council. “Pricing drives consumption,” he said.

Through a spokesman, Mayor Erin Mendenhall, elected in 2019 on a pledge to address climate change and air quality, declined an interview. In a statement, she said the city will consider pricing as a way “to send a stronger conservation signal.”

Homes around Salt Lake boast lush, forest-green lawns, despite the drought. And not always by choice.

Carbon dioxide levels. The amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere hit its highest level ever, scientists said. Humans pumped 36 billion tons of the planet-warming gas into the atmosphere in 2021, more than in any previous year.Understand the Latest News on Climate Change

In the suburb of Bluffdale, when Elie El kessrwany stopped watering his lawn in response to the drought, his homeowners’ association threatened to fine him. “I was trying to do the right thing for my community,” he said.

Robert Spendlove, a Republican state representative, introduced a bill this year that would have blocked communities from requiring homeowners to maintain lawns. He said local governments lobbied against the bill, which failed.

In the state legislative session that ended in March, lawmakers approved other measures that start to address the crisis. They funded a study of water needs, made it easier to buy and sell water rights, and required cities and towns to include water in their long-term planning. But lawmakers rejected proposals that would have had an immediate impact, such as requiring water-efficient sinks and showers in new homes or increasing the price of water.

What the Future May Hold

The worst-case scenario for the Great Salt Lake is neither hypothetical nor abstract. Rather, it’s on display 600 miles southwest, in a narrow valley at the edge of California, where what used to be a lake is now a barely contained disaster.

In the early 1900s, Los Angeles, growing fast and running out of water, bought land along either side of the Owens River, then built an aqueduct diverting the river’s water 230 miles south to Los Angeles.

The river had been the main source of water for what was once Owens Lake, which covered more than 100 square miles. The lake dried up, and then for much of the 20th century it was the worst source of dust pollution in America, according to a 2020 study by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

When wind storms hit the dried lake bed, they kick up PM10 — particulate matter 10 micrometers or smaller, which can lodge in the lungs when inhaled and has been linked to worsened asthma, heart attacks and premature death. The amount of PM10 in the air around Owens Lake has been as much as 138 times higher than deemed safe by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Local officials successfully sued Los Angeles, arguing it had violated the rights of nearby communities to clean air. A judge ordered Los Angeles to reduce the dust. That was 25 years ago. Since then, Los Angeles has spent $2.5 billion trying to keep wind from blowing dust off the lake bed.

The city has tried different strategies: Covering the lake bed in gravel. Spraying just enough water on the dust to hold it in place. Constantly tilling the dry earth, creating low ridges to catch restive dust particles before they can become airborne.

The result is a mix between an industrial site and a science experiment. On a recent morning, workers scurried across the vast area, checking valves and sprinklers that continually get plugged with sand. Nearby, inside a complex that resembles a bunker, walls of screens monitored data to alert the operation’s 70-person staff if something goes wrong. If the carefully calibrated flow of sprinklers is disrupted, for example, dust could quickly start to fly off again.

Dust levels near the lake still sometimes exceed federal safety rules. Among Utah’s coterie of nervous advocates for the Great Salt Lake, Owens Lake has become shorthand for the risks of failing to act quickly enough and the grave damage if the lake dries up, the contents of its bed spinning into the air.

On what used to be the shore of what used to be Owens Lake is what’s left of the town of Keeler. When the lake still existed, Keeler was a boom town. Today it consists of an abandoned school, an abandoned train station, a long-closed general store, a post office that’s open from 10 a.m. to noon, and about 50 remaining residents who value their space, and have lots of it.

“Cheap land,” said Jim Macey, when asked why he moved to Keeler in 1980. He described that period, before Los Angeles began trying to hold down the lake bed, as “the time of dust.” He recalled watching entire houses vanish from sight when the wind blew in.

“We called it the Keeler Death Cloud,” Mr. Macey said.

Science

There's a reason you can't stop doomscrolling through L.A.'s fire disaster

Even for those lucky enough to get out in time, or to live outside the evacuation zones, there has been no escape from the fires in the Los Angeles area this week.

There is hardly a vantage point in the city from which flames or plumes of smoke are not visible, nowhere the scent of burning memories can’t reach.

And on our screens — on seemingly every channel and social media feed and text thread and WhatsApp group — an endless carousel of images documents a level of fear, loss and grief that felt unimaginable here as recently as Tuesday morning.

Even in places of physical safety, many in Los Angeles are finding it difficult to look away from the worst of the destruction online.

“To me it’s more comfortable to doomscroll than to sit and wait,” said Clara Sterling, who evacuated from her home Wednesday. “I would rather know exactly where the fire is going and where it’s headed than not know anything at all.”

A writer and comedian, Sterling is — by her own admission — extremely online. But the nature of this week’s fires make it particularly hard to disengage from news coverage and social media, experts said.

For one, there’s a material difference between scrolling through images of a far-off crisis and staying informed about an active disaster unfolding in your neighborhood, said Casey Fiesler, an associate professor specializing in tech ethics at the University of Colorado Boulder.

“It’s weird to even think of it as ‘doomscrolling,’ ” she said. “When you’re in it, you’re also looking for important information that can be really hard to get.”

When you share an identity with the victims of a traumatic event, you’re more likely both to seek out media coverage of the experience and to feel more distressed by the media you see, said Roxane Cohen Silver, distinguished professor of psychological science at UC Irvine.

For Los Angeles residents, this week’s fires are affecting the people we identify with most intimately: family, friends and community members. They have consumed places and landmarks that feature prominently in fond memories and regular routines.

The ubiquitous images have also fueled painful memories for those who have lived through similar disasters — a group whose numbers have increased as wildfires have grown more frequent in California, Silver said.

This she knows personally: She evacuated from the Laguna Beach fires in 1993, and began a long-term study of that fire’s survivors days after returning to her home.

“Throughout California, throughout the West, throughout communities that have had wildfire experience, we are particularly primed and sensitized to that news,” she said. “And the more we immerse ourselves in that news, the more likely we are to experience distress.”

Absorption in these images of fire and ash can cause trauma of its own, said Jyoti Mishra, an associate professor of psychiatry at UC San Diego who studied the long-term psychological health of survivors of the 2018 Camp fire.

The team identified lingering symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder, depression and anxiety both among survivors who personally experienced fire-related trauma such as injury or property loss, and — to a smaller but still significant degree — among those who indirectly experienced the trauma as witnesses.

“If you’re witnessing [trauma] in the media, happening on the streets that you’ve lived on and walked on, and you can really put yourself in that place, then it can definitely be impactful,” said Mishra, who’s also co-director of the UC Climate Change and Mental Health Council. “Psychology and neuroscience research has shown that images and videos that generate a sense of personal meaning can have deep emotional impacts.”

The emotional pull of the videos and images on social media make it hard to look away, even as many find the information there much harder to trust.

Like many others, Sterling spent a lot of time online during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic. Back then, Sterling said, the social media environment felt decidedly different.

“This time around I think I feel less informed about what’s going on because there’s been such a big push toward not fact-checking and getting rid of verified accounts,” she said.

The rise of AI-generated images and photos has added another troubling kink, as Sterling highlighted in a video posted to TikTok early Thursday.

“The Hollywood sign was not on fire last night. Any video or photos that you saw of the Hollywood sign on fire were fake. They were AI generated,” she said, posting from a hotel in San Diego after evacuating.

Hunter Ditch, a producer and voice actor in Lake Balboa, raised similar concerns about the lack of accurate information. Some social media content she’s encountered seemed “very polarizing” or political, and some exaggerated the scope of the disaster or featured complete fabrications, such as that flaming Hollywood sign.

The spread of false information has added another layer of stress, she said. This week, she started turning to other types of app — like the disaster mapping app, Watch Duty — to track the spreading fires and changing evacuation zones.

But that made her wonder: “If I have to check a whole other app for accurate information, then what am I even doing on social media at all?”

Science

Pink Fire Retardant, a Dramatic Wildfire Weapon, Poses Its Own Dangers

From above the raging flames, these planes can unleash immense tankfuls of bright pink fire retardant in just 20 seconds. They have long been considered vital in the battle against wildfires.

But emerging research has shown that the millions of gallons of retardant sprayed on the landscape to tame wildfires each year come with a toxic burden, because they contain heavy metals and other chemicals that are harmful to human health and the environment.

The toxicity presents a stark dilemma. These tankers and their cargo are a powerful tool for taming deadly blazes. Yet as wildfires intensify and become more frequent in an era of climate change, firefighters are using them more often, and in the process releasing more harmful chemicals into the environment.

Some environmental groups have questioned the retardants’ effectiveness and potential for harm. The efficiency of fire retardant has been hard to measure, because it’s one of a barrage of firefighting tactics deployed in a major fire. After the flames are doused, it’s difficult to assign credit.

The frequency and severity of wildfires has grown in recent years, particularly in the western United States. Scientists have also found that fires across the region have become faster moving in recent decades.

There are also the longer-term health effects of exposure to wildfire smoke, which can penetrate the lungs and heart, causing disease. A recent global survey of the health effects of air pollution caused by wildfires found that in the United States, exposure to wildfire smoke had increased by 77 percent since 2002. Globally, wildfire smoke has been estimated to be responsible for up to 675,000 premature deaths per year.

Fire retardants add to those health and environmental burdens because they present “a really, really thorny trade-off,” said Daniel McCurry, an assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering at the University of Southern California, who led the recent research on their heavy-metal content.

The United States Forest Service said on Thursday that nine large retardant-spraying planes, as well as 20 water-dropping helicopters, were being deployed to fight the Southern California fires, which have displaced tens of thousands of people. Several “water scooper” amphibious planes, capable of skimming the surface of the sea or other body of water to fill their tanks, are also being used.

Two large DC-10 aircraft, dubbed “Very Large Airtankers” and capable of delivering up to 9,400 gallons of retardant, were also set to join the fleet imminently, said Stanton Florea, a spokesman for the National Interagency Fire Center in Boise, Idaho, which coordinates national wildland firefighting efforts across the West.

Sprayed ahead of the fire, the retardants coat vegetation and prevent oxygen from allowing it to burn, Mr. Florea said. (Red dye is added so firefighters can see the retardant against the landscape.) And the retardant, typically made of salts like ammonium polyphosphate, “lasts longer. It doesn’t evaporate, like dropping water,” he said.

The new research from Dr. McCurry and his colleagues found, however, that at least four different types of heavy metals in a common type of retardant used by firefighters exceeded California’s requirements for hazardous waste.

Federal data shows that more than 440 million gallons of retardant were applied to federal, state, and private land between 2009 and 2021. Using that figure, the researchers estimated that between 2009 and 2021, more than 400 tons of heavy metals were released into the environment from fire suppression, a third of that in Southern California.

Both the federal government and the retardant’s manufacturer, Perimeter Solutions, have disputed that analysis, saying the researchers had evaluated a different version of the retardant. Dan Green, a spokesman for Perimeter, said retardants used for aerial firefighting had passed “extensive testing to confirm they meet strict standards for aquatic and mammalian safety.”

Still, the findings help explain why concentrations of heavy metals tend to surge in rivers and streams after wildfires, sometimes by hundreds of times. And as scrutiny of fire suppressants has grown, the Forestry Service has set buffer zones surrounding lakes and rivers, though its own data shows retardant still inadvertently drifts into those waters.

In 2022, the environmental nonprofit Forest Service Employees for Environmental Ethics sued the government in federal court in Montana, demanding that the Forest Service obtain a permit under the Clean Water Act to cover accidental spraying into waterways.

The judge ruled that the agency did indeed need to obtain a permit. But it allowed retardant use to continue to protect lives and property.

Science

2024 Brought the World to a Dangerous Warming Threshold. Now What?

Source: Copernicus/ECMWF

Note: Temperature anomalies relative to 1850-1900 averages.

At the stroke of midnight on Dec. 31, Earth finished up its hottest year in recorded history, scientists said on Friday. The previous hottest year was 2023. And the next one will be upon us before long: By continuing to burn huge amounts of coal, oil and gas, humankind has all but guaranteed it.

The planet’s record-high average temperature last year reflected the weekslong, 104-degree-Fahrenheit spring heat waves that shuttered schools in Bangladesh and India. It reflected the effects of the bathtub-warm ocean waters that supercharged hurricanes in the Gulf of Mexico and cyclones in the Philippines. And it reflected the roasting summer and fall conditions that primed Los Angeles this week for the most destructive wildfires in its history.

“We are facing a very new climate and new challenges, challenges that our society is not prepared for,” said Carlo Buontempo, director of the Copernicus Climate Change Service, the European Union monitoring agency.

But even within this progression of warmer years and ever-intensifying risks to homes, communities and the environment, 2024 stood out in another unwelcome way. According to Copernicus, it was the first year in which global temperatures averaged more than 1.5 degrees Celsius, or 2.7 degrees Fahrenheit, above those the planet experienced at the start of the industrial age.

For the past decade, the world has sought to avoid crossing this dangerous threshold. Nations enshrined the goal in the 2015 Paris agreement to fight climate change. “Keep 1.5 alive” was the mantra at United Nations summits.

Yet here we are. Global temperatures will fluctuate somewhat, as they always do, which is why scientists often look at warming averaged over longer periods, not just a single year.

But even by that standard, staying below 1.5 degrees looks increasingly unattainable, according to researchers who have run the numbers. Globally, despite hundreds of billions of dollars invested in clean-energy technologies, carbon dioxide emissions hit a record in 2024 and show no signs of dropping.

One recent study published in the journal Nature concluded that the absolute best humanity can now hope for is around 1.6 degrees of warming. To achieve it, nations would need to start slashing emissions at a pace that would strain political, social and economic feasibility.

But what if we’d started earlier?

By spewing heat-trapping gases into the atmosphere, humankind has lifted global temperatures to record highs.

If nations had started reducing emissions in 2005, they could have made gradual cuts to limit warming to 1.5 degrees.

Starting in 2015, when the Paris agreement was adopted, would have required steeper cuts.

Starting today would require cuts so drastic as to appear essentially impossible.

“It was guaranteed we’d get to this point where the gap between reality and the trajectory we needed for 1.5 degrees was so big it was ridiculous,” said David Victor, a professor of public policy at the University of California, San Diego.

The question now is what, if anything, should replace 1.5 as a lodestar for nations’ climate aspirations.

“These top-level goals are at best a compass,” Dr. Victor said. “They’re a reminder that if we don’t do more, we’re in for significant climate impacts.”

The 1.5-degree threshold was never the difference between safety and ruin, between hope and despair. It was a number negotiated by governments trying to answer a big question: What’s the highest global temperature increase — and the associated level of dangers, whether heat waves or wildfires or melting glaciers — that our societies should strive to avoid?

The result, as codified in the Paris agreement, was that nations would aspire to hold warming to “well below” 2 degrees Celsius while “pursuing efforts” to limit it to 1.5 degrees.

Even at the time, some experts called the latter goal unrealistic, because it required such deep and rapid emissions cuts. Still, the United States, the European Union and other governments adopted it as a guidepost for climate policy.

Christoph Bertram, an associate research professor at the University of Maryland’s Center for Global Sustainability, said the urgency of the 1.5 target spurred companies of all kinds — automakers, cement manufacturers, electric utilities — to start thinking hard about what it would mean to zero out their emissions by midcentury. “I do think that has led to some serious action,” Dr. Bertram said.

But the high aspiration of the 1.5 target also exposed deep fault lines among nations.

China and India never backed the goal, since it required them to curb their use of coal, gas and oil at a pace they said would hamstring their development. Rich countries that were struggling to cut their own emissions began choking off funding in the developing world for fossil-fuel projects that were economically beneficial. Some low-income countries felt it was deeply unfair to ask them to sacrifice for the climate given that it was wealthy nations — and not them — that had produced most of the greenhouse gases now warming the world.

“The 1.5-degree target has created a lot of tension between rich and poor countries,” said Vijaya Ramachandran, director for energy and development at the Breakthrough Institute, an environmental research organization.

Costa Samaras, an environmental-engineering professor at Carnegie Mellon University, compared the warming goals to health officials’ guidelines on, say, cholesterol. “We don’t set health targets on what’s realistic or what’s possible,” Dr. Samaras said. “We say, ‘This is what’s good for you. This is how you’re going to not get sick.’”

“If we were going to say, ‘Well, 1.5 is likely out of the question, let’s put it to 1.75,’ it gives people a false sense of assurance that 1.5 was not that important,” said Dr. Samaras, who helped shape U.S. climate policy from 2021 to 2024 in the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy. “It’s hugely important.”

Scientists convened by the United Nations have concluded that restricting warming to 1.5 degrees instead of 2 would spare tens of millions of people from being exposed to life-threatening heat waves, water shortages and coastal flooding. It might mean the difference between a world that has coral reefs and Arctic sea ice in the summer, and one that doesn’t.

Each tiny increment of additional warming, whether it’s 1.6 degrees versus 1.5, or 1.7 versus 1.6, increases the risks. “Even if the world overshoots 1.5 degrees, and the chances of this happening are increasing every day, we must keep striving” to bring emissions to zero as soon as possible, said Inger Anderson, the executive director of the United Nations Environment Program.

Officially, the sun has not yet set on the 1.5 target. The Paris agreement remains in force, even as President-elect Donald J. Trump vows to withdraw the United States from it for a second time. At U.N. climate negotiations, talk of 1.5 has become more muted compared with years past. But it has hardly gone away.

“With appropriate measures, 1.5 Celsius is still achievable,” Cedric Schuster, the minister of natural resources and environment for the Pacific island nation of Samoa, said at last year’s summit in Azerbaijan. Countries should “rise to the occasion with new, highly ambitious” policies, he said.

To Dr. Victor of U.C. San Diego, it is strange but all too predictable that governments keep speaking this way about what appears to be an unachievable aim. “No major political leader who wants to be taken seriously on climate wants to stick their neck out and say, ‘1.5 degrees isn’t feasible. Let’s talk about more realistic goals,’” he said.

Still, the world will eventually need to have that discussion, Dr. Victor said. And it’s unclear how it will go.

“It could be constructive, where we start asking, ‘How much warming are we really in for? And how do we deal with that?’” he said. “Or it could look very toxic, with a bunch of political finger pointing.”

Methodology

The second chart shows pathways for reducing carbon emissions that would have a 66 percent chance of limiting global warming this century to 1.5 degrees Celsius above the preindustrial average.

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoThese are the top 7 issues facing the struggling restaurant industry in 2025

-

Culture1 week ago

Culture1 week agoThe 25 worst losses in college football history, including Baylor’s 2024 entry at Colorado

-

Sports1 week ago

Sports1 week agoThe top out-of-contract players available as free transfers: Kimmich, De Bruyne, Van Dijk…

-

Politics1 week ago

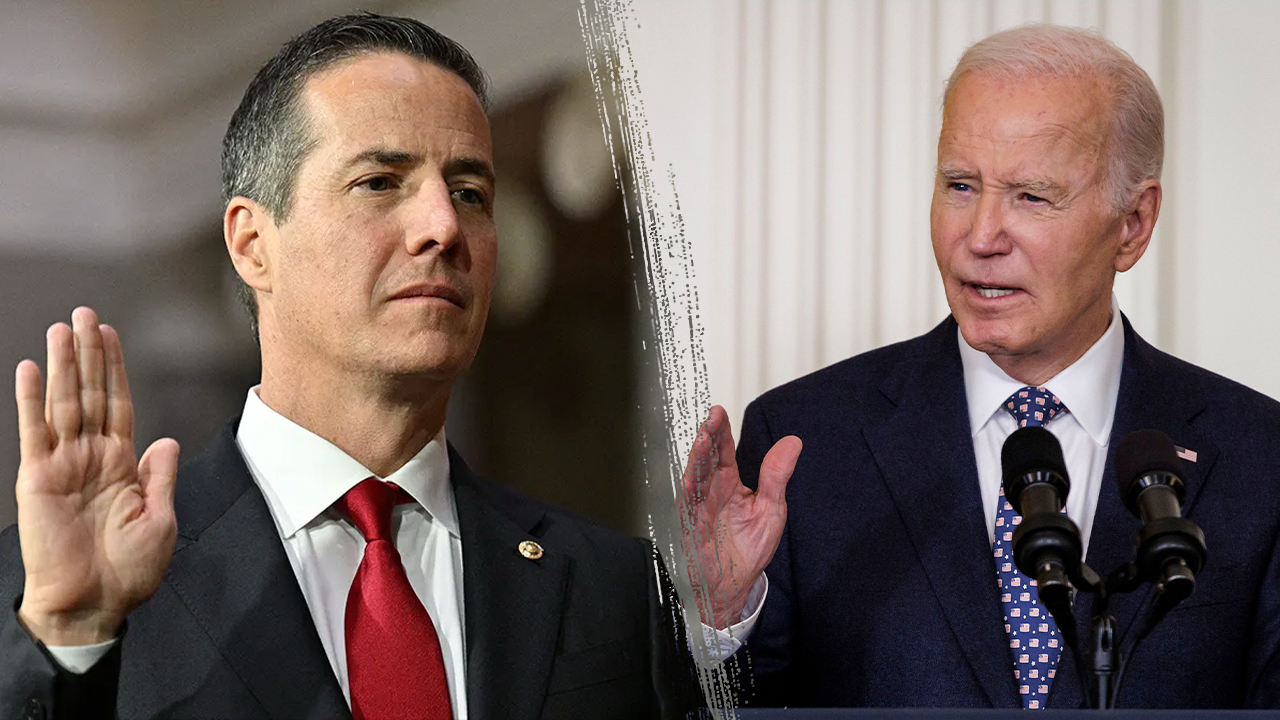

Politics1 week agoNew Orleans attacker had 'remote detonator' for explosives in French Quarter, Biden says

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoCarter's judicial picks reshaped the federal bench across the country

-

Politics6 days ago

Politics6 days agoWho Are the Recipients of the Presidential Medal of Freedom?

-

Health5 days ago

Health5 days agoOzempic ‘microdosing’ is the new weight-loss trend: Should you try it?

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoIvory Coast says French troops to leave country after decades

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23935560/acastro_STK103__03.jpg)