Vermont

Then Again: Early motor vehicles in Vermont made unfortunate history

The longer term arrived in Vermont in 1898. Burlington residents watched in marvel as Dr. J.H. Lindsley putted round in his new Stanley Steamer, which is believed to be the primary vehicle ever pushed in Vermont.

That didn’t imply the state didn’t have already got a legislation governing motor autos. We could also be a law-abiding individuals, however we’re additionally a law-writing individuals. Handed 4 years earlier than Lindsley purchased his automobile from the Stanley Brothers of Massachusetts, the legislation required that anybody “answerable for a carriage, automobile or engine propelled by steam” shall not drive on a public highway with out having an individual “of mature age” strolling a minimum of one-eighth of a mile forward to warn individuals {that a} motorcar was approaching. At night time, this individual was to hold a purple mild.

In a way, these individuals strolling forward with lights might have been warning Vermonters of how a lot vehicles have been going to vary the state. Vermonters have been each enthralled and anxious by these new contraptions. Some labored to advertise automobiles, whereas different Vermonters devoted themselves to regulating or outright banning them.

Dr. Horatio Nelson Jackson of Burlington was one of many promoters. In a well-publicized stunt, he turned the primary individual to drive cross-country by automobile, taking 63 days to journey from San Francisco to New York.

The going was by no means straightforward. Although the US had greater than 2 million miles of roads on the time, solely 150 of these miles have been paved. Jackson figured the journey set him again $8,000, factoring within the buy of the automobile, the wage of the driver-mechanic who accompanied him, and the price of the gasoline and a number of repairs alongside the best way.

Add to that $6 for the ticket he acquired when he returned to Burlington after the journey. He’d been caught exceeding the 6-mph velocity restrict. That was fairly quick sufficient, the Legislature had lately determined when it set statewide velocity limits. Six miles per hour was the restrict in village, city and metropolis facilities. Outdoors of settled areas, drivers have been welcome to hit 15 mph.

These conservative limits most likely made sense. Consider the world vehicles have been getting into: Horses have been ubiquitous and didn’t combine effectively with automobiles; pedestrians have been unfamiliar with find out how to work together with automobiles; the talents of latest drivers, which might have been everybody, have been most likely restricted; early vehicles had abysmal security data; and highway circumstances have been poor.

As a part of state oversight of vehicles, the Legislature began requiring drivers to register their autos in 1904. Motor autos have been nonetheless luxurious objects, so by 1906, Vermont nonetheless had solely 373 of them.

To Joseph Battell, that was precisely 373 too many. “Let the homeowners of the freeway dragons construct their very own roads,” snarled Battell.

Because of a big inheritance, Battell was wealthy and highly effective. He additionally had a factor for horses. Battell bought a 500-acre farm in Weybridge for the selective breeding of a horse lengthy related to Vermont, the Morgan.

Battell’s love of horses fed his hatred of vehicles. “It’s not possible that highways can be utilized with security and luxury by the 2 strategies of journey,” he declared.

Battell fought vehicles in a number of methods. As a state legislator, he launched a invoice to ban motor visitors on the Hancock-Ripton Street, which, not coincidentally, ran previous the inn he owned in Ripton. However the invoice failed.

When the legislative method failed, he attacked the problem much less like a sage lawmaker and extra like an unhinged and vindictive neighbor. Battell took to erecting limitations and spreading particles within the highway close to his inn. When the Legislature discovered of his actions, it criminalized such conduct.

Making unlucky historical past

Battell had nonetheless one other method of combating this new invasive species. He owned a newspaper, the Middlebury Register, and stuffed its pages with reprinted tales about automobile crashes, particularly these involving girls and kids.

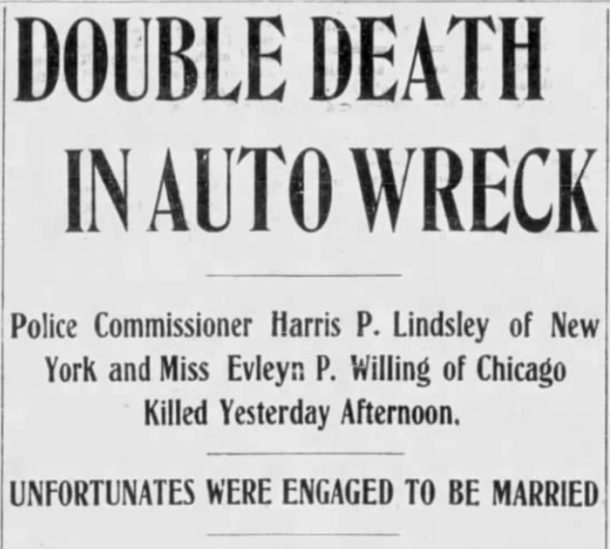

Battell actually would have identified of the incident that occurred Aug. 14, 1905. That day, the intriguingly named Harris Lindsley, maybe associated to the Burlington physician who owned the state’s first motorcar, had the unlucky distinction of creating historical past on the roads of Vermont.

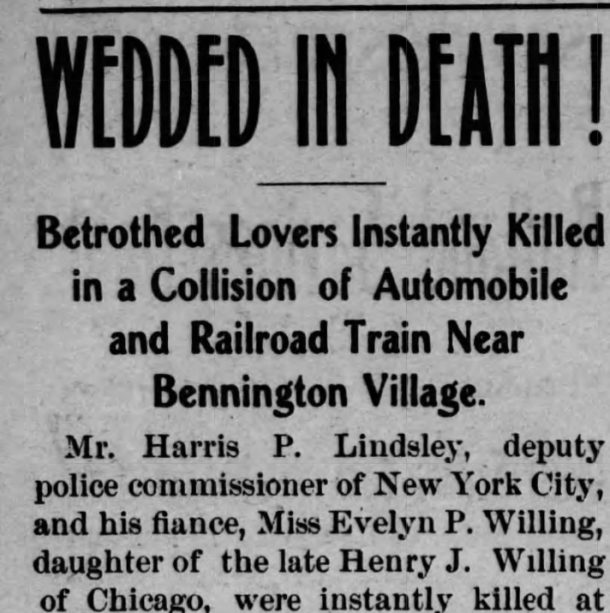

This Lindsley, who was a deputy police commissioner of New York Metropolis, was touring Vermont together with his fiancée, Evelyn Pierpont Keen, an heiress from a outstanding Chicago household. Keen, whose late mom had Vermont roots, had taken to summering on the Equinox in Manchester. She was there for a few weeks in 1905 with members of the family, together with an aunt and youthful cousin. Some individuals later mentioned Keen and Lindsley have been to be married the next week; others claimed that they had but to make formal wedding ceremony plans.

That afternoon in August, the couple have been heading north to Manchester after visiting Williamstown, Massachusetts, in the course of the day. They rode within the again seat of Keen’s 60-horsepower Mercedes, a “massive touring machine,” as one newspaper account described it, with brass plates marked “1041” and “Metropolis of Chicago” — the state of Illinois hadn’t but began issuing plates. Up entrance have been Keen’s 13-year-old cousin Ambrose Cramer and the chauffeur, J.A. Adamson.

Because the automobile approached Pike’s Crossing, a railroad crossing simply north of Bennington, Adamson accelerated due to an incline. If he glimpsed the approaching prepare, he might need hit the gasoline more durable. The entrance of the automobile cleared the tracks earlier than the prepare struck. The again seat bore the brunt of the impression.

The collision threw the auto about 60 toes. The prepare, which consisted of solely a locomotive and passenger automobile, derailed. The prepare automobiles slowly rolled over and got here to relaxation about 10 or 15 toes from the tracks, about 100 toes of which have been torn up within the wreck. The engineer and fireman each managed to leap to security. Not one of many prepare’s 15 passengers was severely injured.

The impression crushed the auto, which caught hearth. Adamson and Cramer survived the crash with some unhealthy cuts and bruises. Lindsley and Keen weren’t so fortunate. They have been thrown towards a close-by fence with such pressure that they knocked it down, in response to one newspaper report.

They turned the primary two individuals killed in an vehicle accident in Vermont. A subsequent investigation discovered that the prepare had been driving backward (that’s, with the engine within the rear) towards Bennington on the time of the crash. The place of the engineer blocked his view of the approaching automobile.

A state railroad committee, nevertheless, laid many of the blame on Adamson for not stopping on the crossing, seeing or listening to the prepare, and for dashing.

Newspapers repeated claims that Cramer, the teenage boy, was on the wheel on the time of the accident, a declare the chauffeur denied. The Waterbury File reported that Keen and Lindsley might need been the victims of the “auto craze for making excessive velocity,” with the automobile reaching 30 to 40 miles per hour in pursuit of a second vehicle that they have been racing.

After the accident, the our bodies of Lindsley and Keen lay in state on the Mark Skinner Library in Manchester, which was in-built honor of a former Vermont governor. It may appear an odd use for a library, however Keen was Skinner’s granddaughter, and her mom had donated the library to the city.

Keen was buried in Manchester’s Dellwood Cemetery. A prepare transported Lindsley’s physique south to Grand Central Station in New York, the place a crowd greeted it. Dozens of army and cops, some mounted and others on foot, accompanied the casket to a army armory — Lindsley was a veteran — the place his physique lay in state. The following day, 600 cops and 900 members of Lindsley’s former regiment escorted the casket because it was transported again to Grand Central Station for the lengthy journey again to Vermont, the place Lindsley was buried beside his fiancée.

Joseph Battell will surely have argued that the lovers’ graves have been a stern warning of the unacceptable risks posed by vehicles. However it was an argument he would lose.

3,000 books in 30 days

Our journalism is made attainable by member donations. VTDigger is partnering with the Youngsters’s Literacy Basis (CLiF) throughout our Spring Member Drive to ship 3,000 new books to Vermont youth liable to rising up with low literacy abilities. Make your donation and ship a e book as we speak!

Vermont

Support for regrowing Haiti’s forests has roots in Vermont – VTDigger

The Bicknell’s thrush, a small, brown songbird, faces dual environmental threats: In its summer home among New England’s tallest peaks, such as Vermont’s Mount Mansfield, climate change is altering the landscape, and could push out the scrubby vegetation it favors for nesting.

In the winter, the thrush takes flight, traveling more than 1,500 miles to Hispaniola, the Caribbean island home to Haiti and the Dominican Republic. Particularly in Haiti, a history of colonization has contributed to sprawling deforestation, leaving only a fraction of the country covered in forest.

Now, members of a group co-founded by Vermont biologist Julia Pupko and Haitian organizer Jean-Fenel Dorvilier are attempting to mend the wounds of deforestation, both for the sake of wildlife like the Bicknell’s thrush, and for Haitian residents who need forests to sustain their communities. The group is based in Duchity, a rural municipality in southwestern Haiti.

The organization, called Society for the Reforestation of Duchity, Haiti, was founded in 2020 and has filled a gap left by Vermont Haiti Project, a nonprofit organization that began providing humanitarian services in rural Haiti in 2007. The Vermont Haiti Project provided mentorship to the new organization before it disbanded in December 2023.

Before it was colonized by the Spanish in the late 1400s, the island of Hispaniola was largely covered in forest, Pupko said. France colonized the western part of the island in the 1600s, now known as Haiti. Enslaved people in Haiti rebelled against the French, winning independence in 1804 — but the United States, France and others stifled the country’s development, and France required Haiti to pay it reparations, they noted. All the while, forest cover decreased.

”A lot was accomplished by cutting down valuable timber trees such as mahogany species, and also exporting things like indigo and sugar and other cash crops, which you also typically will deforest to do,” Pupko said.

The United States later occupied Haiti from 1915 until 1934, and during that time, forest cover dropped from 60% to around 20% as the U.S. converted land for agricultural use, Pupko said. Political turmoil within the country more recently has contributed to change on the landscape, too, they said.

As a child, Dorvilier’s birthday fell on Haiti’s Arbor Day, so he’d spend the day planting trees, an act that fostered his appreciation for forests. He volunteered with the Vermont Haiti Project, bringing volunteers into the mountains to place seedlings into the earth.

That’s where he met Pupko, who got involved with the Vermont Haiti Project as a student at University of Vermont. Pupko currently works as a forestry specialist with the Vermont Department of Forest, Parks and Recreation, a post that is unrelated to their involvement with the organization.

Though Pupko and Dorvilier spoke different languages at the time, they came to know each other through their shared interest in forests.

“We kind of just spent a lot of time together, sharing words for trees, sharing words for different things, and really understood that both of us had a deep love for trees,” Pupko said. “We stayed in touch over the years and began developing a stronger friendship over that time, continuing to circle back to our shared love of forests and trees and reforestation, which culminated in 2020 in our decision to form a reforestation and agroforestry organization together.”

The Duchity reforestation project’s mission is distinct from that of the Vermont Haiti Project. The latter was primarily focused on public health, with projects that ranged from starting a medical clinic, improving access to clean water and providing disaster relief after the devastating 2010 earthquake in Haiti.

The new organization is focused on regrowing forest and improving the environment in Duchity. Its largest project takes place on Arbor Day, when members work with local schools and community members to plant trees. They host workshops on different topics, showing how to harvest large tree branches to use for construction, for example, without cutting the entire tree. Last May, 100 participants planted more than 1,000 trees during the event.

Its efforts could help wildlife like the Bicknell’s thrush. While the bird is not listed as federally threatened or endangered, Partners in Flight, a group that tracks bird populations, ranks the species on its Red Watch list, its highest level of concern.

Pupko pointed to literature showing evidence that the bird uses regenerating forests and agroforestry plots in the locations where it spends its winter.

But the reforestation group’s goals, Pupko said, are centered around the community as much as the environment. It manages 36 acres of forest in two locations, which serve as an educational space and a resource for community members who can harvest products from them. If someone needs lumber to build a home, the organization’s staff — most of whom are from the community or live in Haiti — will work with them to sustainably harvest trees, Pupko said. In exchange, those who take from the forest are asked to help maintain it.

“Our projects come from a number of agronomists and agroforesters that are from Duchity or surrounding (areas),” Pupko said. “When we’re working on projects, they talk to the elders in the community. They talk to the youth in the community. They have these big meetings that all different stakeholders are coming to and are bringing up different issues they want to address.”

Those, then, are incorporated into their plans, Pupko said.

The organization operates by “emphasizing meeting the needs of the community in the work that we do as our primary objective, so that’s ensuring people have the tools and materials to be implementing these projects,” they said. But that mission “cannot be separated from the importance of overall ecosystem health and conservation.”

The two issues are inseparable, Pupko said, for many reasons: Large tracts of forest prevent mudslides after severe rains and hurricanes; the immediate environment is healthier for people and wildlife; an improved ecosystem can help clean water and improve agriculture.

One of the organization’s projects involves eight farmers who work with the reforestation group to implement or support sustainable farming practices.

“A lot of times, that’s providing seedlings,” Pupko said. “It may also be providing tools. Some farmers, they may know exactly what agroforestry strategy they want to implement and exactly how to care for the trees. But for other people, they may not know. So then in that case, we would provide them with the educational resources that they would need in order to successfully do this.”

Farmers and other community members approve of the organization, Dorvilier said in an interview, which made him understand that “this is something we can continue doing.”

“Now, we have about 35 people working with us in the community,” he said.

Dorvilier’s concerns about forests run deep. Without them, animals disappear and agriculture becomes harder, he said.

“Without trees, I think there is no life,” he said.

That sentiment could apply to a bird Vermont conservationists have been concerned about for years. But efforts to protect the Bicknell’s thrush’s habitat in Vermont and New England only go so far, Pupko said.

“If you ignore where they spend half of their year, their overwintering habitat, there’s no way that the species can continue to thrive,” they said.

“There’s many different creatures that migrate as winter falls here,” Pupko said. “The deep connection that is formed through sharing these miraculous species is really special and something that I think is worth supporting.”

Vermont

The US State That Produces The Most Maple Syrup By A Million Gallons – Chowhound

Maple syrup is one of those ingredients that has a lot of fans, and for good reason. It’s tasty, sweet, and can be used for so much more than just pancakes and waffles. Maple syrup takes eggnog to the next level, it makes a perfect cheap vanilla substitute, and it’s even the sweet addition your egg salad has been craving.

Many people think maple syrup is produced solely in Canada since it’s the global leader in the maple syrup business. But there are quite a few states in America that produce maple syrup, with Vermont being the absolute king of maple syrup production in the entire country. In 2024 alone, Vermont was responsible for making over 3 million gallons of maple syrup.

With U.S. maple syrup production reaching 5.86 million gallons in 2024, Vermont cranked out more than half of all the maple syrup in the entire country. The state also produced double the amount of the state that took second place. New York only produced 846,000 gallons of maple syrup in 2024, less than half of that of Vermont.

Maple syrup production in the United States

U.S. maple syrup is primarily produced in Vermont and New York. Maine and Wisconsin also produce maple syrup, but the output from each of these states is only a little over half of what New York produces. As of 2023, the only other states producing maple syrup on a commercial scale include Michigan, Pennsylvania, and New Hampshire.

Although states like Ohio, Connecticut, Massachusetts, Minnesota, and Indiana have produced maple syrup in the past, their contributions in 2024 were each less than 100,000 gallons. The West Coast sees even less maple syrup production, with only a handful of commercial maple syrup farms in Washington state and none in California or Oregon, as of 2023.

Overall, Vermont accounted for 49% of the crops needed for maple syrup production in the United States, in 2023, followed by New York with a total of 18%. Maine took third place, showing just 11% of the country’s maple syrup crop. But while global maple syrup production faces uncertain seasons, and a continuously changing climate, the sugarmakers who brought about 2024’s boon in U.S. supply are to thank for that sweet, gooey, drizzle of maple syrup currently dripping down the short stack of buttermilk pancakes in your mind.

Vermont

Franklin County flock tests positive for bird flu

A flock of quail, guinea fowl, ducks and chickens tested positive for bird flu in Franklin County last week, according to Vermont’s Agency of Agriculture, Food and Markets (AAFM).

The owners of the flock notified state officials on Dec. 18, after one of their birds died suddenly and others became sick.

State officials tested the birds the next day, and a laboratory in Iowa later confirmed the birds had contracted highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI), also known as H5N1 bird flu.

It’s the fourth instance of avian flu in a domestic flock in Vermont since spring 2022.

“The recent cases are sort of tied to the migratory bird population moving around,” said Scott Waterman, a spokesperson for AAFM.

Importantly, Waterman said, lab testing also confirmed that this latest set of cases are not tied to the flu strain currently impacting dairy herds in other states.

However, the agency is urging people who own poultry and cattle to take precautions to limit their animals’ contact with wild birds.

“That’s where the wild bird-HPAI crossover happens, is when your domestic poultry start to interact with the wild bird population,” Waterman said.

He said domestic birds can catch the virus if they congregate with wild birds at a pond or if they have contact with the feces of wild birds.

Waterman said people can limit their animals’ risk of contracting the virus by cleaning coops regularly, fencing poultry in and taking care to quarantine cattle and birds that arrive from another farm.

It’s also important, he said, to wash and sterilize boots and clothing that’s come into contact with other animals.

Bird flu is deadly for most domestic poultry, and much of the Franklin County flock died from the disease. AAFM worked with the owners to euthanize the remaining birds.

The Vermont Department of Health is monitoring people who had close contact with the infected birds. At this time, no humans have tested positive for the disease in Vermont or in New England.

The Health Department said the risk of a human contracting bird flu in Vermont is low, but officials still advise wearing personal protective equipment if you work with bird or cattle feces, litter or raw milk.

You can find more information about bird flu in humans on the Health Department’s website.

Have questions, comments or tips? Send us a message.

-

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24924653/236780_Google_AntiTrust_Trial_Custom_Art_CVirginia__0003_1.png)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24924653/236780_Google_AntiTrust_Trial_Custom_Art_CVirginia__0003_1.png) Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoGoogle’s counteroffer to the government trying to break it up is unbundling Android apps

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoNovo Nordisk shares tumble as weight-loss drug trial data disappoints

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoIllegal immigrant sexually abused child in the U.S. after being removed from the country five times

-

Entertainment1 week ago

Entertainment1 week ago'It's a little holiday gift': Inside the Weeknd's free Santa Monica show for his biggest fans

-

Lifestyle1 week ago

Lifestyle1 week agoThink you can't dance? Get up and try these tips in our comic. We dare you!

-

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25672934/Metaphor_Key_Art_Horizontal.png)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25672934/Metaphor_Key_Art_Horizontal.png) Technology5 days ago

Technology5 days agoThere’s a reason Metaphor: ReFantanzio’s battle music sounds as cool as it does

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoFrance’s new premier selects Eric Lombard as finance minister

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoOn a quest for global domination, Chinese EV makers are upending Thailand's auto industry