Vermont

How did gay marriage become legal? How civil unions paved the way 25 years ago.

Gay marriage, once an unpopular concept nationwide, is widely accepted in Vermont today.

“People take for granted that same-sex couples can get married nowadays,” said Bill Lippert, 75, one of Vermont’s first openly gay lawmakers. “You can reference your husband or wife casually now in conversation. But if you weren’t around 25 years ago, there isn’t always an appreciation for how hard we had to fight.”

April 26 marks the 25th anniversary of civil unions – marriage for same-sex couples in all but name – becoming state law. Although civil unions were deeply controversial even among Vermonters at the time, they served as the first pivotal step toward full marriage equality, Lippert said.

In 2000, Vermont became the first place in the world to grant marriage-equivalent legal rights to same-sex couples. Domestic partnerships existed in some places, but those unions “usually only granted a few legal rights,” Lippert said.

“The eyes of the whole country and world were focused on what Vermont was doing in 2000,” said Lippert, who helped craft the civil unions bill while serving on the house judiciary committee.

Three years later Massachusetts became the first state to legalize gay marriage, followed by Connecticut and Iowa in 2008. Vermont followed suit in 2009. Several more states legalized same-sex marriage before U.S Supreme Court finally made it nationwide law in 2015 through the Obergefell v. Hodges case.

“One can see the direct connection between what Vermont did in 2000 with civil unions to what followed in Massachusetts and eventually with Obergefell in 2015,” Lippert said.

Life before civil unions

Prior to the creation of civil unions, gay and lesbian couples lacked “a thousand more rights” than married straight couples, Lippert said, no matter how long they had been together.

For instance, if one partner in a same-sex relationship was in hospital, the other partner did not automatically have the power of attorney.

“That was one of the most painful ones,” Lippert said.

Lippert recalled one particularly egregious case that happened to a lesbian couple with a child. When the partner who had given birth to the child died in a car crash, her parents fought for custody even though the two women had been raising the kid together.

“The list goes on and on,” Lippert said.

Although Vermont eventually established “second parent adoption” in 1993, there still wasn’t a “legal connection between partners,” Lippert noted.

“That side of the triangle was missing,” he said.

The road to civil unions: ‘The Baker Case’

In the late 90s, three lawyers and three same-sex couples decided it was time to test Vermont’s marriage laws.

In 1998, three Vermont same-sex couples applied for marriage licenses in Chittenden County. When their marriages were denied, they filed a lawsuit that became known as Baker v. Vermont, or informally ‘the Baker Case,’ after the last name of one of the plaintiffs. A Vermont Superior Court judge ruled to dismiss the case, so the plaintiffs made an appeal to the Vermont Supreme Court.

What the Vermont Supreme Court did next shocked everyone. Instead of either legalizing gay marriage or striking down the case, the justices ruled in 1999 that same-sex couples should be afforded all the same legal rights as heterosexual couples but left it up to the Vermont legislature whether to grant gay couples the ability to marry or form an equivalent union.

“Personally, I was shocked because I had been assured by the attorneys fighting for gay marriage that we would never have to vote on it in the legislature,” Lippert said. “Many of my colleagues were, frankly, beyond anxious – terrified – because they never wanted to deal with the issue because it was so controversial.”

At the time, some states were changing their constitutions to outlaw gay marriage. The Defense of Marriage Act also went into effect two years prior. In Vermont specifically, only 20% of residents supported gay marriage.

Gay marriage “was not a popular proposal,” Lippert recalled. “It was hotly condemned and fought against by major religious groups as an affront to their religious sacraments.” One of their main fears was that churches would be forced to marry gay couples.

‘Separate but equal’

The Vermont legislature was already in mid-session when the court dropped the issue of gay marriage in their laps. The house judicial committee, where Lippert served as vice chair, was tasked with writing the bill that would grant gay couples the right to marry or to form an equivalent union.

After listening to weeks of testimony from supporters and opponents of gay marriage, the committee voted to create a “parallel legal structure,” which they named civil unions, Lippert said.

“It was very disappointing for the attorneys and advocates, but it was clear that we did not have the votes to create full marriage for same-sex couples,” said Lippert, who was among the three committee members to vote for gay marriage.

Some gay marriage advocates at the time found the idea of civil unions insulting and akin to the concept of “Separate but equal.”

Some activists said civil unions were like “having to sit on the back of the bus” and refused to support the bill, Lippert said. “Others said, ‘At least we’re on the bus.’”

The lawsuit plaintiffs and their attorneys decided “it was better to pass something achievable than pass something that would fail and then get nothing,” Lippert said.

Victory uncertain

On the day house reps were scheduled to vote, Lippert and his committee members weren’t sure if they had enough support to pass civil unions in house. Some representatives wouldn’t share their plans, while others kept saying they “needed more information” before they could decide which way to vote.

For some representatives, a “yes” vote guaranteed they would lose their seats in either the primary or general elections later that year.

“Until the roll call, none of us knew we were going to win,” said Lippert. “It would have taken a few votes to switch and we would have lost.”

After 12 hours of debate and testimony that day, the Vermont house voted 76-69 to pass the civil unions bill.

Lippert primarily attributed the win to “courageous” gay Vermonters, loved ones and other advocates who shared personal stories throughout the bill process. Some gay people even came out publicly for the first time to throw their support behind the bill.

Lippert also thinks the “hateful phone calls and letters” legislators received made them realize why civil unions were necessary.

“They saw why we needed this,” Lippert said. “That if this is the level of prejudice and hatefulness that comes at me, what must it be like for gay people? The hate backfired.”

Once civil unions passed the house, it was much smoother sailing for gay advocates. The senate, which had a higher percentage of Democrats than the house, passed civil unions 19-11.

Gov. Howard Dean, who already voiced his approval of civil unions, signed the bill into law soon after – albeit behind closed doors and without fanfare.

“He said publicly that marriage for same-sex couples made him uncomfortable” but that he could back civil unions, Lippert remembered. Even still, Dean’s support was “crucial.”

“If he hadn’t been willing to say he would sign the bill, I don’t think we would have passed it,” Lippert said. “People wouldn’t have risked voting for it.”

The aftermath

Later that year, 17 legislators who voted for civil unions in April 2000 lost their seats to opponents who promised to help repeal the institution. Dean, who had to wear a bulletproof vest during his gubernatorial campaign, also faced an ardent anti-civil unions challenger.

“It’s hard to explain the level of controversy and some of the hatefulness directed at the governor and lawmakers,” Lippert said.

The following session, the now more conservative house managed to repeal civil unions by one vote, but the effort died in the senate.

Between 2000 and 2009, thousands of gay couples from other states and nations traveled to Vermont to enter civil unions. They wanted legal recognition of their relationship somewhere even if their home state or country wouldn’t respect it, Lippert said.

“At the time, I would have been happy to have settled the case in court,” Lippert said. “But looking back, I think it would have garnered greater backlash if the court had granted gay marriage or an equivalent institution directly.”

That’s what happened in Hawaii. In 1996, the Hawaiian Supreme Court ruled that it was unconstitutional to deny marriage to same-sex couples. An enormous public backlash ensued, and by 1998, Hawaiians had changed their state constitution to outlaw gay marriage.

Amending Vermont’s constitution wouldn’t have been as easy – it takes multiple years versus only one in Hawaii – but there definitely were some lawmakers who wanted to, Lippert said. Such an amendment never got off the ground, however.

“My view is civil unions was a historic step for civil marriage for same-sex couples,” Lippert said. “Saying that full marriage equality was important does not take away from civil unions moving us to marriage equality in a profound way.”

Lippert and his spouse eventually entered a civil union themselves. They then got married once Vermont legalized what Lippert now calls “full marriage equality.”

Vermont

Medicare Advantage plans are leaving Vermont. Now what? – VTDigger

Bouncing from plan to plan for Medicare coverage has become an inadvertent, annual tradition for Becky Beerwald.

When she moved to Essex Junction from the Connecticut coast in 2023, she selected a Medicare Advantage plan before it was discontinued for the following year. Then she enrolled in a Vermont Blue Advantage plan, only for the insurer to announce in October that it would not offer the plans in 2026. This fall, she went back to the drawing board but in an insurance landscape almost entirely stripped of the Medicare Advantage plans that nearly 51,000 people in the state had relied on.

Beerwald is just one of the thousands of Vermonters trying to make sense of the coverage that remains available now that Medicare Advantage has essentially left the state.

READ MORE

This year’s open enrollment period for Medicare, which runs through Dec. 7, has been a “challenging one,” said Sam Carleton, who directs the State Health Insurance Program, a state entity that provides guidance for Medicare beneficiaries. The small office has been flooded with inquiries since the start of October, when BlueCross Blue Shield and United Healthcare’s departures from the Advantage market became public. Agewell, the elderly support agency Carleton leads in Northwestern Vermont has also seen a surge in interest for the webinars they offer to explain how Medicare works and how people can get the coverage they need under it.

Medicare is the federal health insurance program for people 65 and older and those with certain disabilities.

Medicare has four parts: Part A covers inpatient care while Part B broadly covers outpatient care, medical devices and preventative care, among other things. Together, these two are regarded as original Medicare. It generally covers 80% of the cost of services, meaning many people who opt for traditional Medicare coverage also opt for something known as a Medigap plan, or supplemental insurance, sold by a private insurer that can help cover the remaining 20% of costs.

Medicare Part D offers prescription drug coverage, which is also provided by a private insurer.

Part C plans bundle all of that — and often include additional benefits like dental, or vision. These plans, known as Medicare Advantage plans, are offered by private insurers.

While many people like their Advantage plans, others can feel trapped in them because they require approval before covering some drugs and services and often require people to see in-network providers.

When the insurers providing Medicare Advantage plans in Vermont announced the end to their coverage, it gave some people a welcomed exit ramp from plans that are otherwise difficult to leave, explained Kaj Samsom, the commissioner of the Department of Financial Regulation, the state office that regulates insurers.

“This event, as really truly unfortunate as it is for folks who are no longer in Medicare Advantage and no longer have other options, there are some people who are probably happy,” Samsom said.

100vw, 1200px”/><figcaption class=)

When an insurer withdraws a plan, it triggers something called a special enrollment period, which comes with different privileges than the regular open enrollment period.

In particular, it means people searching for new plans get something called “Guaranteed Issue Rights.” These rights mean that insurance companies cannot charge someone more for their insurance based on pre-existing health conditions — things like diabetes or cancer — that would make care more expensive for the insurer to pay out.

When someone is new to Medicare and enrolling for the first time, they are also protected from this type of underwriting. But after that initial enrollment, Medigap plans can reject or charge sicker patients more based on their health history. Samsom referred to this as the “one way street” of Medicare Advantage, where individuals can’t switch to traditional Medicare without the massive cost of a Medigap supplement plan looming over them.

Now, nearly all Vermonters who bought Medicare Advantage plans will need to opt into original Medicare, with the option to buy the supplemental Medigap plans — protected from underwriting during this special enrollment.

The issue of underwriting became particularly concerning to Beerwald. As she scoured the best Medigap plan, she said some insurers asked for her health history, despite her guaranteed issue rights.

When open enrollment began, Beerwald said she started calling the insurers offering the least expensive Medigap plans for 2026: Medco, State Farm and Aflac.

Each insurer offers a selection of Medigap plans: A, B, C, D, F, G. These letter plans are standardized, so that plans with the same letter include the same benefits, no matter which insurer sells them. Price should be the only difference.

Beerwald said she wants a G plan because it offers the best coverage with the most diverse beneficiary pool — because of a 2015 law, people who became eligible for Medicare after 2020 can’t buy Medigap plans C or F. That restriction effectively leaves plans’ pool older. Plans D and G now offer similar coverage, without the age restriction.

100vw, 1200px”/><figcaption class=) A slide from a webinar titled “Age Well Medigap” organized by the State Health Insurance Assistance Program on Tuesday, Nov. 25. Screenshot via YouTube

A slide from a webinar titled “Age Well Medigap” organized by the State Health Insurance Assistance Program on Tuesday, Nov. 25. Screenshot via YouTube“My mother lived until almost 102 my dad was 87, so I’ve got a long life ahead of me,” Beerwald said. “I don’t want to be in the older pool, I want to be in the younger pool.”

She said she worries that as the pools under plans C and F grow older and smaller over time, their premiums will soar or the plans could disappear altogether.

“I don’t want to be in the lurch again. I want to be in the popular plan with the popular kids,” she said.

Insurers she found that honored the guaranteed issue rights for plan G charged higher premiums. She did notice, however, that insurers would honor these rights for C and F plans.

Eventually, she bought a TVHP Medigap Blue Plan G from BlueCross BlueShield of VT, for about $258 per month, she said.

Still, the fact that she encountered some insurers who would not honor the guaranteed issue for every letter plan conflicted with her understanding of how the law should protect that right.

Beerwald’s quest to understand and rectify this issue offers a window onto the maelstrom that can arise when private insurers are tasked with delivering a government service. She said she reached out to the state office tasked with regulating insurers, their consumer protection line, U.S. Rep. Becca Balint’s office, SHIP and Carleton, in an attempt to make sense of it all.

“I certainly feel that frustration. I mean, you’re in a circumstance where you’ve lost your insurance, you received notice from the federal government that you are getting a special enrollment period, and you’re able to get another plan. You’ve done the legwork. … You’ve made a choice, and you then call this insurance company, those insurance companies say sure we’ll sell you a policy, but only if you send us all your medical records. That stinks,” Carleton said.

However, Carleton and the Department of Regulation told Beerwald — and confirmed to VTDigger — that it is legal for insurers to not apply guaranteed issue rights to every letter plan.

It comes down to one small matter of wording in the regulation that applies to Medigap plans: “It’s a ‘must’ for (plans) A, B, C, F,” Department of Regulation Deputy Commissioner Mary Block said. “It’s a ‘may’ for G, for people before that 2020 date.”

“So some insurance companies will offer it, some will not,” she added.

There’s nothing the state can do to rectify this frustration, according to Block, since federal law dictates Medigap plan regulations.

“In Vermont, we don’t have the discretion to say Plan G is always going to be available to everybody,” she said.

Block added that other consumers have run into confusion when dealing with insurance brokers, who may not be aware of which customers are receiving guaranteed issue rights and may mix up forms.

The best way to combat that, Samson said, is for people to advocate for themselves and make it very clear when they are on the phone that they need the guaranteed issue rights.

Beerwald remains unsatisfied with their explanation.

Now, the only remaining Medicare Advantage plans in the state are Humana plans in six counties — including Orange, Windham and Windsor, where many of the available care comes from providers in the Dartmouth Health network. However, Dartmouth Health has long been out of network for Humana. During a Nov. 19 town hall with the Vermont congressional delegation, Balint raised particular concern over this and cautioned beneficiaries in those counties to choose new plans.

Carleton assured that even in the counties where Humana remains, if people have lost their other Advantage plan, they should still receive guaranteed issue rights for Medigap plans if they chose to buy one and opt into original Medicare.

“What prompts the special enrollment period is your plan leaving, not necessarily the loss of all Medicare Advantage plans,” he said.

Carleton said he worries about the overall sticker shock that comes with Medigap plans, and fears some people will opt into original Medicare and forgo supplemental plans, leaving them vulnerable to the 20% of costs that original Medicare doesn’t cover.

Beerwald said she’s going to end up paying more than $7,500 for insurance this year. After her Medigap plan, she said she’s buying a drug plan, vision and hearing plans, as well as a dental plan, to cover the cost of extensive dental work she needs

She said she worries not just for herself but for other older adults who are not as savvy as navigating all the pitfalls of the insurance system. But for now, she is locked in to her BlueCross BlueShield’s plan for at least a year and whatever 2026 may have in store.

Vermont

Vermont Joins Virginia, Washington, New Mexico, South Carolina, Minnesota and Others in Facing Successive Decline in US Tourism Last Month: Everything You Need to Know – Travel And Tour World

Published on

November 26, 2025

Vermont, Virginia, Washington, New Mexico, South Carolina, Minnesota, and others saw a decline in US tourism last month due to lingering pandemic effects and changing travel trends. This successive downturn in tourism across multiple states highlights a broader shift in the nation’s travel landscape. While Vermont’s scenic autumn landscapes and winter sports once attracted droves of visitors, it too faced a significant drop in tourism. Similarly, Virginia’s rich historical offerings, Washington’s urban and outdoor attractions, and New Mexico’s unique cultural experiences all saw fewer travelers. States like South Carolina and Minnesota, known for their coastal resorts and outdoor adventures, are also feeling the impact. As traveler preferences evolve and the effects of the pandemic continue to reverberate, the U.S. tourism industry faces significant challenges, with states across the country working hard to adapt and recover.

Vermont’s Tourism in Trouble: A 25.10% Decline

Vermont, a state renowned for its breathtaking fall foliage and outdoor adventures, has suffered a staggering 25.10% decline in tourism. Visitors, who typically flock to Vermont for its charming autumn landscapes and winter sports, have been deterred by the lasting effects of the pandemic and changing travel habits. The state’s tourism industry, heavily reliant on seasonal visitors, has taken a major hit. Local businesses, from quaint inns to ski resorts, are facing significant challenges as Vermont works to find ways to attract tourists back.

Virginia’s Slight Dip: A 1.39% Decline in Visitor Arrivals

Virginia, home to a rich historical heritage and scenic landscapes, has experienced a relatively modest decline in tourism, down by 1.39%. Despite its cultural treasures, like Monticello and Williamsburg, and natural beauty such as the Blue Ridge Mountains, the state has seen fewer travelers in recent years. The pandemic and the evolving travel landscape have influenced this slight dip, though Virginia’s tourism sector remains resilient. Efforts to promote outdoor experiences and historical sites are aimed at restoring the state’s appeal to history buffs and nature lovers alike.

Washington: A Major Drop of 18.55% in Tourism

Washington state, a hub for both urban excitement and natural wonders, has seen a dramatic 18.55% decline in tourism. Known for its iconic landmarks like the Space Needle and Mount Rainier, as well as its outdoor offerings, Washington’s tourism sector has been impacted by travel restrictions and shifts in traveler preferences. International and corporate travel has dropped, and many potential visitors are seeking alternative destinations. Washington is working hard to revive its tourism industry by focusing on its vast outdoor activities and urban attractions to draw back eager travelers.

New Mexico: A Small But Steady Decline of 1.27%

New Mexico, famous for its unique blend of Native American culture, art, and stunning landscapes, has experienced a 1.27% drop in tourism. The state’s appeal lies in its desert vistas, historic pueblos, and vibrant arts scene, but changing travel trends and lingering effects of the pandemic have led to fewer visitors. While the decline is small, it signals the need for New Mexico to continue to adapt and highlight its cultural experiences and outdoor adventures in order to attract more travelers to its one-of-a-kind destinations.

South Carolina’s Struggles: A Sharp 27.90% Drop

South Carolina has faced a devastating 27.90% decline in tourism, with its renowned coastal attractions, including Myrtle Beach and Charleston, feeling the brunt of the downturn. The state’s tourism sector, which thrives on beach resorts, golf courses, and rich history, has been hit hard by reduced demand. The COVID-19 pandemic and changing traveler preferences for closer, more accessible destinations have further deepened the impact. South Carolina is working to bounce back by focusing on its charm as a vacation spot for relaxation, history, and culture.

Minnesota’s Setback: A 7.33% Decline in Visitor Numbers

Minnesota, known for its picturesque lakes and outdoor adventures, has experienced a 7.33% decline in tourism. The state’s natural beauty, including the Boundary Waters and its many parks, typically draws nature enthusiasts, but the pandemic and evolving travel trends have slowed this influx. With fewer travelers seeking distant adventures, Minnesota’s tourism industry has faced setbacks. Nevertheless, the state continues to push its outdoor offerings and festivals, hoping to revive interest and bring visitors back to enjoy its scenic landscapes and unique attractions.

Conclusion

Vermont, Virginia, Washington, New Mexico, South Carolina, Minnesota, and others have all experienced a decline in U.S. tourism last month, marking a troubling trend that reflects broader shifts in the travel industry. The lingering effects of the pandemic continue to disrupt tourism, with many travelers altering their habits and seeking more accessible, closer destinations. These states, known for their unique attractions—from Vermont’s fall foliage and Virginia’s historical landmarks to South Carolina’s beaches and New Mexico’s cultural heritage—are feeling the impact of changing travel preferences.

Vermont, Virginia, Washington, New Mexico, South Carolina, Minnesota, and others saw a decline in US tourism last month due to lingering pandemic effects and changing travel trends.

As the industry navigates these challenges, states are focusing on adapting to new trends in order to revitalize their tourism sectors and attract visitors once again.

Vermont

Hannaford stores in Vermont are under scrutiny

Protestors again demonstrated outside Hannaford locations in Vermont over working conditions for migrant dairy farmworkers, the News & Citizen reports. It was the second time in over a year that rallies were held for the cause.

Advocates are urging Ahold Delhaize, the parent company of Ahold Delhaize USA and owner of the Hannaford brand, to join the immigrant rights group Migrant Justice’s Milk with Dignity program. The program asks participating companies to pay more for dairy products so that working conditions on dairy farms can improve.

Distributor Vermont Way Foods announced a partnership in October that allows Migrant Justice to monitor working conditions in its dairy supply network.

Ahold Delhaize USA has not responded to a request for comment.

Migrant Justice accuses Hannaford of human rights violations in its dairy supply chain. According to a survey by the organization, most farmworkers in Vermont earn less than minimum wage and report suffering injuries due to working conditions.

Ahold Delhaize recently conducted a human rights investigation involving farms that produce Hannaford-brand milk, and the results are pending.

During the protests, Hannaford increased its security presence, which included the Morristown Police Department and the Lamoille County Sheriff’s Department, to ensure that people parking in Hannaford lots were there to buy groceries.

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoFrance and Germany support simplification push for digital rules

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoCourt documents shed light on Indiana shooting that sparked stand-your-ground debate

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoSinclair Snaps Up 8% Stake in Scripps in Advance of Potential Merger

-

Science5 days ago

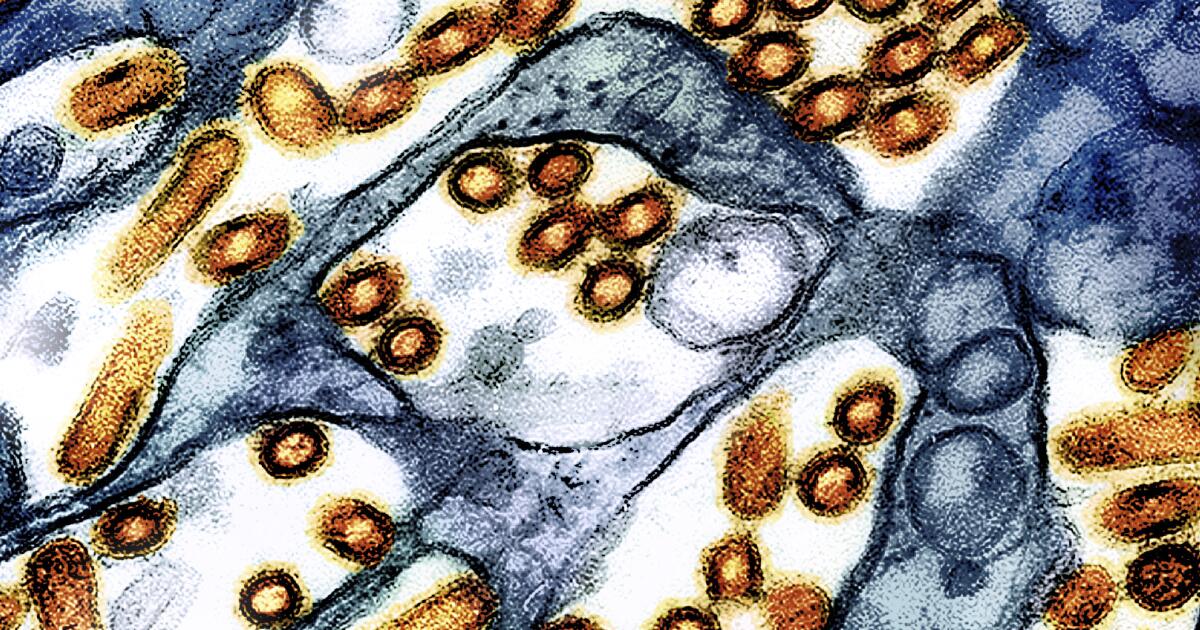

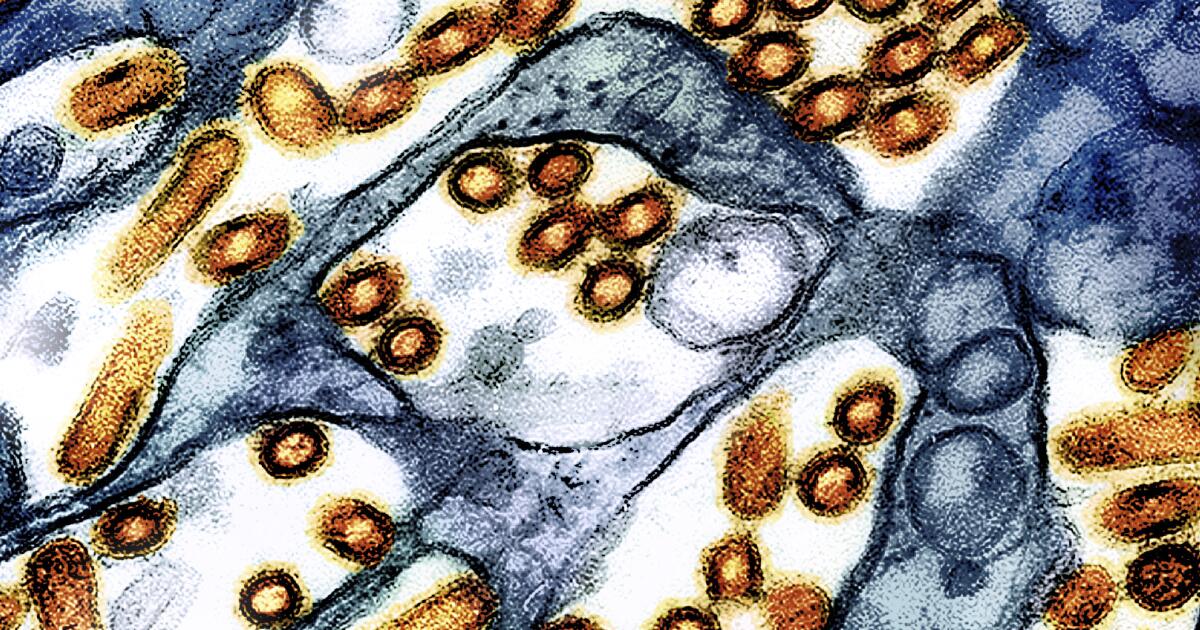

Science5 days agoWashington state resident dies of new H5N5 form of bird flu

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoCalls for answers grow over Canada’s interrogation of Israel critic

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoDuckworth fires staffer who claimed to be attorney for detained illegal immigrant with criminal history

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoFake flight cancellation texts target travelers

-

Culture1 week ago

Culture1 week agoDo You Recognize These Past Winners of the National Book Award?