New York

Beverly Moss Spatt, Protector of Landmarks in New York, Dies at 99

Beverly Moss Spatt, a fierce defender of New York City’s aesthetic and cultural heritage who battled real estate and political interests to protect distinguished buildings and historic districts as chairwoman of the city’s Landmarks Preservation Commission in the 1970s, died on Friday in Brooklyn. She was 99.

Her son, David, on Monday confirmed her death, at N.Y.U. Langone Hospital-Brooklyn.

A Brooklyn judge’s daughter who grew up talking civics at the breakfast table, Ms. Spatt was on the City Planning Commission in the 1960s and became known as a shameless do-gooder. She got out and spoke to people in the neighborhoods, carried their fights to City Hall and developed a low tolerance for back room deals. It was, she said, a good foundation for landmarks preservation work.

More than a decade after wreckers demolished Pennsylvania Station and historical preservation had become a gospel of city planners, Ms. Spatt led the landmarks commission through years of controversy, from 1974 to 1978 as chairwoman, then as a member until 1982. Throughout, she stood up to powerful developers and their allies in her efforts to protect architectural treasures and significant neighborhoods by giving them landmark status.

In her years at the helm, more than 800 landmarks were so designated — mansions, Broadway theaters, apartment and commercial buildings, gems like the New York County Courthouse in Foley Square, historic districts on the Upper East Side, scenic spaces in Central Park and Verdi Square in Manhattan, and even the magnificent interiors of City Hall and the New York Public Library on Fifth Avenue.

The triumph of Ms. Spatt’s tenure was Grand Central Terminal, saved by the courts from a bankrupt Penn Central Company that had fought landmark status for years to erect a 55-story office tower over the station, at East 42nd Street and Park Avenue. Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis had played a highly visible role, but it was a coalition of city officials and civic activists in the Municipal Art Society that spearheaded the drive to save that classical Beaux-Arts terminal.

“It is the most important decision that the preservation movement has ever had,” Ms. Spatt said in 1977, when the Court of Appeals, New York’s highest, handed down the ruling. (The ruling was confirmed by the United States Supreme Court in 1978.) It saved not only Grand Central, she noted, but also the landmark commission itself and the principle of landmark laws: to protect historic and cultural treasures even when it meant economic hardship for an owner.

“Especially when a city is in financial distress, it should not be forced to choose between witnessing the demolition of its glorious past and mortgaging its hopes for the future,” the court declared. “The landmark preservation provisions of the Administrative Code represent an effort to take a middle way.”

Ms. Spatt, who was 41 when she got into government, often presided over tumultuous public hearings, whipping off her reading glasses in confronting property owners or developers in debate. Writing streams of letters to newspapers, she carried on running battles with political opponents, seeing herself as neither liberal nor conservative but rather as a guardian of the commission’s prerogative to designate landmarks, which restricts demolition or alteration of buildings and limits development inconsistent with a neighborhood’s character.

In the 1970s, many developers regarded her as a meddling women’s liberationist — she had been a member of assorted women’s organizations — whose ideals had run amok, restricting their rights, robbing them of fair returns on investments and imposing unreasonable business costs and conditions. Courts often agreed, and removed landmark status. The commission also reversed itself in hardship cases.

Widening the geography and concept of landmarks, the Spatt commission designated as such the cantilevered Queensboro Bridge and several Brooklyn sites, including Gage & Tollner’s seafood restaurant, Grand Army Plaza and tree-lined Ocean Parkway, designed by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux.

It also conferred landmark status on firehouses, police stations, skyscrapers, monuments and, in a nod to social significance, the First Houses on the Lower East Side, dedicated in 1935 as the nation’s first low-income public housing project.

“In this designation,” Ms. Spatt said, “we honor a great social experiment — the responsibility of society to provide for every human being decent housing with a high quality humane environment.”

In 2015, when the Frick Collection on Fifth Avenue proposed a renovation that would have eliminated a garden for more interior space for its art work, a long-retired Ms. Spatt joined a coalition of architects, designers and former landmarks commissioners to fight the plan, citing a 40-year-old Frick promise, made on Ms. Spatt’s watch, to create the garden as a “permanent” feature. Confronted with the evidence of a 1975 news release, the Frick backed off and said it would consider other options.

Beverly Moss was born in Brooklyn on May 26, 1924, one of three daughters of Maximilian and Grace (Leff) Moss. Her father was a Surrogate Court judge and former president of New York City’s Board of Education. She grew up in Brooklyn Heights and lived there at her death.

She graduated from James Madison High School in 1941 and from Brown University in 1945 before earning a master’s degree and a doctorate in urban planning at New York University.

In 1946, she married Dr. Samuel Spatt, an internist. They had three children, Robin, Jonathan and David. Dr. Spatt died in 2007. She is survived by her three children and three grandchildren.

Ms. Spatt joined the League of Women Voters, the Citizens Union and the Women’s City Club, and helped found the Brooklyn Democratic reform movement in the 1950s. In 1965, Mayor Robert F. Wagner appointed her to the City Planning Commission, the agency that approves zoning and land-use permits and sites for urban renewal and other major projects.

She mastered arcane zoning and planning concepts, talked to experts and ordinary citizens and in the neighborhoods became a visible face of distant government. In her five years on the commission, its two chief undertakings were the World Trade Center and a Master Plan for the city. She voted against both, calling the trade center too overwhelming for its site and the Master Plan a mix of “liberal generalities.”

She often dissented on zoning changes, usually on those that smacked of political deals, and opposed “incentive bonuses” for builders who promised “amenities” like plazas in exchange for taller buildings and larger sites. She won a loyal following, rare for an obscure official in an agency that made few headlines but was vital to homeowners and the quality of life in the city.

Mayor John V. Lindsay, a frequent target of her criticism, did not reappoint Ms. Spatt in 1970. There was an uproar by union leaders, citizens’ groups and City Council members. The New York Times called her a “people’s advocate,” saying: “She has been available to the public, accustomed as it is to the bureaucratic runaround. In these days of deepening neighborhood trouble, people are convinced she cares.”

It did no good. But Ms. Spatt was not dismayed. “I realized they weren’t fighting for me, Beverly Spatt, but for a principle,” she said. “It transcends me. People are not supporting me; they’re supporting the right of the people to know.”

Ms. Spatt wrote “A Proposal to Change the Structure of City Planning: Case Study of New York City” (1971). Mayor Abraham D. Beame named her to lead the landmarks commission. She was not reappointed when Mayor Edward I. Koch took office in 1978, but remained a commission member until 1982. For years she taught planning, preservation, housing policy and community advocacy at Barnard College and was a special assistant to Bishop Joseph Sullivan of Brooklyn.

Ms. Spatt’s passion for landmarks was often personal. In 1974, she dashed into the press room at City Hall and shouted, “Someone has stolen one of my buildings!”

It was true, in a way. Cast-iron facade panels of an 1849 building designed by James Bogardus, dismantled and stored in Lower Manhattan pending reconstruction, had vanished. They were eventually found in a Bronx junkyard. But they disappeared once more in 1977.

“My building has been stolen again,” she complained. “It’s a terrible loss.”

New York

New York’s Chinese Dissidents Thought He Was an Ally. He Was a Spy.

The Chinese government’s paranoia about overseas dissidents can seem strange, considering the enormous differences in power between exiled protesters who organize marches in America and their mighty homeland, a geopolitical and economic superpower whose citizens they have almost no ability to mobilize. But to those familiar with the Chinese Communist Party, the government’s obsession with dissidents, no matter where in the world they are, is unsurprising. “Regardless of how the overseas dissident community is dismissed outside of China, its very existence represents a symbol of hope for many within China,” Wang Dan, a leader of the Tiananmen Square protests who spent years in prison before being exiled to the United States in 1998, told me. “For the Chinese Communist Party, the hope for change among the people is itself a threat. Therefore, they spare no effort in suppressing and discrediting the overseas dissident community — to extinguish this hope in the hearts of people at home.”

To understand the party’s fears about the risks posed by dissidents abroad, it helps to know the history of revolutions in China. “Historically, the groups that have overthrown the incumbent government or regime in China have often spent a lot of time overseas and organized there,” says Jessica Chen Weiss, a professor of China studies at Johns Hopkins University. The leader Sun Yat-sen, who played an important role in the 1911 revolution that dethroned the Qing dynasty and led eventually to the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, spent several periods of his life abroad, during which he engaged in effective fund-raising and political coordination. The Communist Party’s own rise to power in 1949 was partly advanced by contributions from leaders who were living overseas. “They are very sensitive to that potential,” Weiss says.

“What the Chinese government and the circle of elites that are running China right now fear the most is not the United States, with all of its military power, but elements of unrest within their own society that could potentially topple the Chinese Communist Party,” says Adam Kozy, a cybersecurity consultant who worked on Chinese cyberespionage cases when he was at the F.B.I. Specifically, Chinese authorities worry about a list of threats — collectively referred to as the “five poisons” — that pose a risk to the stability of Communist rule: the Uyghurs, the Tibetans, followers of the Falun Gong movement, supporters of Taiwanese independence and those who advocate for democracy in China. As a result, the Chinese government invests great effort in combating these threats, which involves collecting intelligence about overseas dissident groups and dampening their influence both within China and on the international stage.

Controlling dissidents, regardless of where they are, is essential to China’s goal of projecting power to its own citizens and to the world, according to Charles Kable, who served as an assistant director in the F.B.I.’s national security branch before retiring from the bureau at the end of 2022. “If you have a dissident out there who is looking back at China and pointing out problems that make the entire Chinese political apparatus look bad, it will not stand,” Kable says.

The leadership’s worries about such individuals were evident to the F.B.I. right before the 2008 Beijing Olympics, Kable told me, describing how the Chinese worked to ensure that the running of the Olympic flame through San Francisco would not be disrupted by protesters. “And so, you had the M.S.S. and its collaborators deployed in San Francisco just to make sure that the five poisons didn’t get in there and disrupt the optic of what was to be the best Olympics in history,” Kable says. During the run, whose route was changed at the last minute to avoid protesters, Chinese authorities “had their proxies in the community line the streets and also stand back from the streets, looking around to see who might be looking to cause trouble.”

New York

Hochul Seeks to Limit Private-Equity Ownership of Homes in New York

Gov. Kathy Hochul of New York on Thursday proposed several measures that would restrict hedge funds and private-equity firms from buying up large numbers of single-family homes, the latest in a string of populist proposals she intends to include in her State of the State address next week.

The governor wants to prevent institutional investors from bidding on properties in the first 75 days that they are on the market. Her plan would also remove certain tax benefits, such as interest deductions, when the homes are purchased.

The proposals reflect a nationwide effort by mostly Democratic lawmakers to discourage large firms from crowding out individuals or families from the housing market by paying far above market rate and in cash, and then leasing the homes or turning them into short-term rentals.

Activists and some politicians have argued that this trend has played a role in soaring prices and low vacancy rates — though low housing production is widely viewed as the main driver of those problems.

If Ms. Hochul was inviting a fight with the real estate interests who have backed her in the past, she did not seem concerned. She even borrowed a line from Jimmy McMillan, who ran long-shot candidacies for governor and mayor as the founder of the Rent Is Too Damn High Party.

“The cost of living is just too damn high — especially when it comes to the sky-high rents and mortgages New Yorkers pay every month,” Ms. Hochul said in a written statement.

James Whelan, president of the Real Estate Board of New York, said his team would review the proposal, but characterized it as “another example of policy that will stifle investment in housing in New York.”

The plan — the specifics of which will be negotiated with the Legislature — is one of several recent proposals the governor has made with the goal of addressing the state’s affordability crisis. Voters have expressed frustration about the high costs of housing and basic goods in the state. This discontent has led to political challenges for Ms. Hochul, who is likely to face rivals in the 2026 Democratic primary and in the general election.

In 2022, five of the largest investors in the United States owned 2 percent of the country’s single-family rental homes, most of them in Sun Belt and Southern states, according to a recent report from the federal Government Accountability Office. The report stated that it was “unclear how these investors affected homeownership opportunities or tenants because many related factors affect homeownership — e.g., market conditions, demographic factors and lending conditions.”

Researchers at Harvard University found that “a growing share of rental properties are owned by business entities and medium- and large-scale rental operators.”

State officials were not able to offer a complete picture of how widespread the practice was in New York. They said local officials in several upstate cities had told them about investors buying up dozens of homes at a time and turning them into rentals.

The New York Times reported in 2023 that investment firms were buying smaller buildings in places like Brooklyn and Queens from families and smaller landlords.

Ms. Hochul’s concern is that these purchases make it harder for first-time home buyers to gain a foothold in the market and can lead to more rental price gouging.

“Shadowy private-equity giants are buying up the housing supply in communities across New York, leaving everyday homeowners with nowhere to turn,” she said in a statement on Thursday. “I’m proposing new laws and policy changes to put the American dream of owning a home within reach for more New Yorkers than ever before.”

Cracking down on corporate landlords became a prominent talking point in last year’s presidential election. On the campaign trail, Vice President Kamala Harris called on Congress to pass previously introduced legislation eliminating tax benefits for large investors that purchase large numbers of homes.

“It can make it impossible then for regular people to be able to buy or even rent a home,” Ms. Harris said last summer.

In August, Representative Pat Ryan, Democrat of New York, called on the Federal Trade Commission to investigate price gouging by private-equity firms in the housing market. He cited a study that estimated that private-equity firms “are expected to control 40 percent of the U.S. single-family rental market by 2030.”

Statehouses across the country have recently looked at ways to tackle corporate homeownership. One effort in Nevada, which passed the Legislature but was vetoed by Gov. Joe Lombardo, proposed capping the number of units a corporation could buy in a calendar year. It was opposed by local chambers of commerce and the state’s homebuilders association.

A bill was introduced in the Minnesota State Legislature that would ban the conversion of homes owned by corporations into rentals. It has yet to come up for a vote.

At the federal level, Senator Jeff Merkley, Democrat of Oregon, and Representative Adam Smith, Democrat of Washington, introduced joint legislation that would force hedge funds to sell all the single-family homes they own over 10 years.

New York

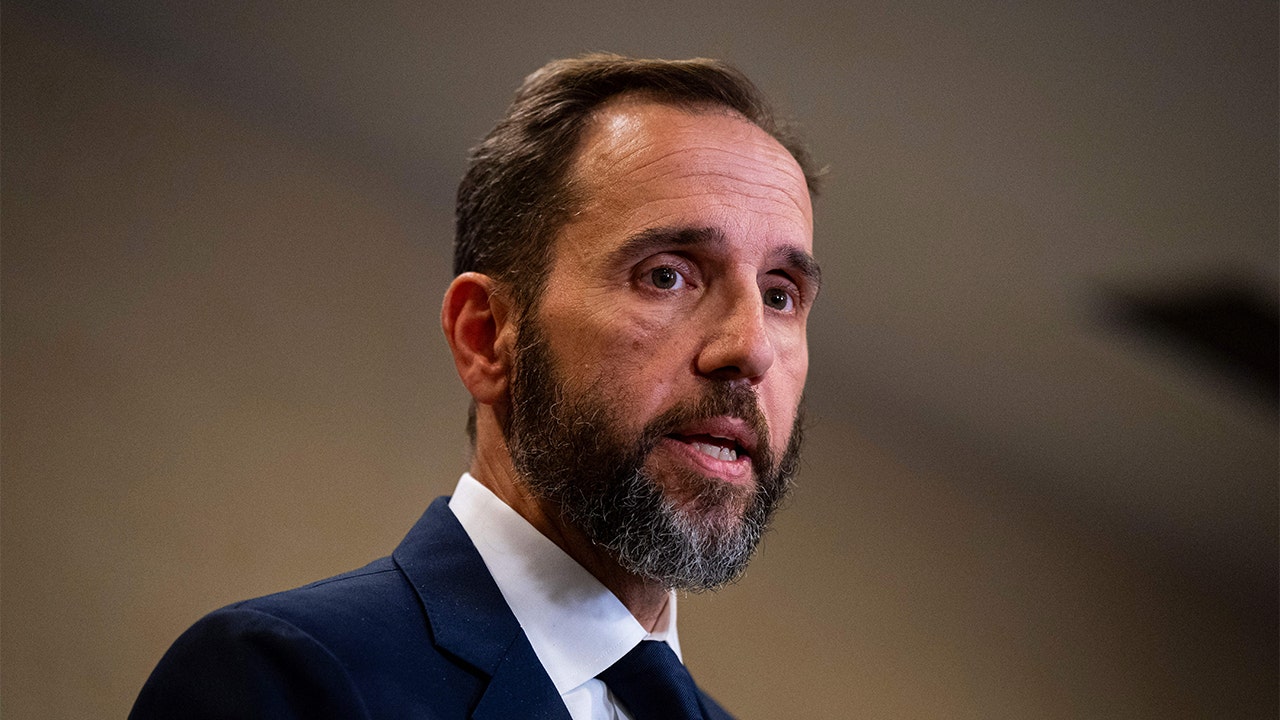

N.Y. Prosecutors Urge Supreme Court to Let Trump’s Sentencing Proceed

New York prosecutors on Thursday urged the U.S. Supreme Court to deny President-elect Donald J. Trump’s last-ditch effort to halt his criminal sentencing, in a prelude to a much-anticipated ruling that will determine whether he enters the White House as a felon.

In a filing a day before the scheduled sentencing, prosecutors from the Manhattan district attorney’s office called Mr. Trump’s emergency application to the Supreme Court premature, saying that he had not yet exhausted his appeals in state court. They noted that the judge overseeing the case plans to spare Mr. Trump jail time, which they argued undermined any need for a stay.

The prosecutors, who had secured Mr. Trump’s conviction last year on charges that he falsified records to cover up a sex scandal that endangered his 2016 presidential campaign, implored the Supreme Court to let Mr. Trump’s sentencing proceed.

“There is a compelling public interest in proceeding to sentencing,” they wrote, and added that “the sanctity of a jury verdict and the deference that must be accorded to it are bedrock principles in our Nation’s jurisprudence.”

The district attorney’s office has so far prevailed in New York’s appellate courts, but Mr. Trump’s fate now rests in the hands of a friendlier audience: a Supreme Court with a 6-to-3 conservative majority that includes three justices Mr. Trump appointed. Five are needed to grant a stay.

Their decision, coming little more than a week before the inauguration, will test the influence Mr. Trump wields over a court that has previously appeared sympathetic to his legal troubles.

In July, the court granted former presidents broad immunity for official acts, stymying a federal criminal case against Mr. Trump for trying to overturn the 2020 election. (After Mr. Trump won the 2024 election, prosecutors shut down that case.)

The revelation that Mr. Trump spoke this week by phone with one of the conservative justices, Samuel A. Alito Jr., has fueled concerns that he has undue sway over the court.

Justice Alito said he was delivering a job reference for a former law clerk whom Mr. Trump was considering for a government position. But the disclosure alarmed ethics groups and raised questions about why a president-elect would personally handle such a routine reference check.

It is unclear whether Justice Alito will recuse himself from the decision, which the court could issue promptly.

Mr. Trump’s sentencing is scheduled to begin at 9:30 a.m. Friday in the same Lower Manhattan courtroom where his trial took place last spring, when the jury convicted him on all 34 felony counts.

If the Supreme Court rescues Mr. Trump on Thursday, returning him to the White House on Jan. 20 without the finality of being sentenced, it will confirm to many Americans that he is above the law. Almost any other defendant would have been sentenced by now.

“A sentencing hearing more than seven months after a guilty verdict is aberrational in New York criminal prosecutions for its delay, not its haste,” the prosecutors wrote.

The prosecutors also noted that Mr. Trump would most likely avoid any punishment at sentencing. The trial judge, Juan M. Merchan, has signaled he plans to show Mr. Trump leniency, reflecting the practical impossibility of incarcerating a president.

Still, Mr. Trump’s lawyers argued that the sentencing could impinge on his presidential duties. It would formalize Mr. Trump’s conviction, cementing his status as the first felon to occupy the Oval Office.

That status, Mr. Trump’s lawyers wrote in the filing to the Supreme Court, would raise “the specter of other possible restrictions on liberty, such as travel, reporting requirements, registration, probationary requirements and others.”

The court’s immunity ruling also underpinned Mr. Trump’s request to halt his sentencing. In the application, Mr. Trump’s lawyers argued that he was entitled to full immunity from prosecution — as well as sentencing — because he won the election.

“This court should enter an immediate stay of further proceedings in the New York trial court,” the application said, “to prevent grave injustice and harm to the institution of the presidency and the operations of the federal government.”

Mr. Trump’s application was filed by two of his picks for top jobs in the Justice Department: Todd Blanche, Mr. Trump’s choice for deputy attorney general, and D. John Sauer, his selection for solicitor general.

“Forcing President Trump to prepare for a criminal sentencing in a felony case while he is preparing to lead the free world as president of the United States in less than two weeks imposes an intolerable, unconstitutional burden on him that undermines these vital national interests,” they wrote.

Whether that argument will prevail is uncertain. Some legal experts have doubted the merits of Mr. Trump’s application, and lower courts have greeted his arguments with skepticism.

Earlier Thursday, a judge on the New York Court of Appeals in Albany, the state’s highest court, declined to grant a separate request from Mr. Trump to freeze the sentencing.

Prosecutors noted that Mr. Trump had yet to have a full appellate panel rule on the matter, and that he had not mounted a formal appeal of his conviction. Consequently, they argued, the Supreme Court “lacks jurisdiction over this non-final state criminal proceeding.”

Also this week, a judge on the First Department of New York’s Appellate Divison in Manhattan rejected the same request to halt the sentencing.

That judge, Ellen Gesmer, grilled Mr. Trump’s lawyer at a hearing about whether he had found “any support for a notion that presidential immunity extends to president-elects?”

With no example to offer, Mr. Blanche conceded, “There has never been a case like this before.”

In their filing Thursday, prosecutors echoed Justice Gesmer’s concerns, noting that “This extraordinary immunity claim is unsupported by any decision from any court.”

They also argued that Mr. Trump’s claims of presidential immunity fell short because their case concerned a personal crisis that predated his first presidential term. The evidence, they said, centered on “unofficial conduct having no connection to any presidential function.”

The state’s case centered on a sex scandal involving the porn star Stormy Daniels, who threatened to go public about an encounter with Mr. Trump, a salacious story that could have derailed his 2016 campaign.

To bury the story, Mr. Trump’s fixer, Michael D. Cohen, negotiated a $130,000 hush-money deal with Ms. Daniels.

Mr. Trump eventually repaid him. But Mr. Cohen, who was the star witness during the trial, said that Mr. Trump orchestrated a scheme to falsify records and hide the true purpose of the reimbursement.

Although Mr. Trump initially faced sentencing in July, his lawyers buried Justice Merchan in a flurry of filings that prompted one delay after another. Last week, Justice Merchan put a stop to the delays and scheduled the sentencing for Friday.

Mr. Trump faced four years in prison, but his election victory ensured that time behind bars was not a viable option. Instead, Justice Merchan indicated that he would impose a so-called unconditional discharge, a rare and lenient alternative to jail or probation.

“The trial court has taken extraordinary steps to minimize any burdens on defendant,” the prosecutors wrote Thursday.

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoThese are the top 7 issues facing the struggling restaurant industry in 2025

-

Culture1 week ago

Culture1 week agoThe 25 worst losses in college football history, including Baylor’s 2024 entry at Colorado

-

Sports1 week ago

Sports1 week agoThe top out-of-contract players available as free transfers: Kimmich, De Bruyne, Van Dijk…

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoNew Orleans attacker had 'remote detonator' for explosives in French Quarter, Biden says

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoCarter's judicial picks reshaped the federal bench across the country

-

Politics6 days ago

Politics6 days agoWho Are the Recipients of the Presidential Medal of Freedom?

-

Health5 days ago

Health5 days agoOzempic ‘microdosing’ is the new weight-loss trend: Should you try it?

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoIvory Coast says French troops to leave country after decades