New Hampshire

Who is this man? Police say child sex assault suspect was living under false identity

Police in Manchester, New Hampshire, are seeking the public’s help in determining the identity of a man charged with sexually assaulting a child in the city last year.

Manchester police say the man, who had claimed to be 60-year-old Angel Rivera Laureano, was brought to the attention of their Juvenile Unit in January of 2024 after someone alleged that he had sexually abused a child under the age of 13. He was ultimately arrested and charged with one count of aggravated felonious sexual assault.

During the investigation, police said they learned that the suspect might not be who he said he was. As a result of their investigation, police were able to determine that the man had been living under a false identity for years, and under that name was convicted of numerous crimes in New Hampshire dating back over a decade.

The real Angel Rivera Laureano was positively identified and located living in Puerto Rico, police said.

The suspect in the sexual assault case, who police are now referring to as “John Doe,” now faces an additional charge of identity fraud. At the time of his arrest he was already being held at the Hillsborough County House of Corrections, and he remains there.

Police said the man’s identity is still unknown, and are asking anyone with information about him to call Detective Guy Kozowyk at 603-792-5560 or email him at gkozowyk@manchesternh.gov.

New Hampshire

Man killed in NH snowmobile crash

An Alton man is dead after a snowmobile crash in New Hampshire’s North Country Thursday afternoon.

The New Hampshire Department of Fish and Game says 63-year-old Bradford Jones was attempting to negotiate a left hand turn on Corridor Trail 5 in Colebrook when he lost control of his snowmobile, struck multiple trees off the side of the trail and was thrown from the vehicle shortly before 3:30 p.m.

Jones was riding with another snowmobiler, who was in the lead at the time of the crash, according to the agency. Once the other man realized Jones was no longer behind him, he turned around and traveled back where he found Jones significantly injured, lying off the trail beside his damaged snowmobile.

The man immediately rendered aid to Jones and called 911 for assistance, NH Fish and Game said. The Colebrook Fire Department used their rescue tracked all terrain vehicle and a specialized off road machine to transport first responders across about a mile of trail to the crash scene.

Once there, a conservation officer and 45th Parallel EMS staff attempted lifesaving measures for approximately an hour, but Jones ultimately died from his injuries at the scene of the crash, officials said.

The crash remains under investigation, but conservation officers are considering speed for the existing trail conditions to have been a primary factor in this deadly incident.

New Hampshire

The weight of caregiving in NH. Why we need SB 608: Sirrine

Recently, I met with a husband who had been caring for his wife since her Alzheimer’s diagnosis. Her needs were escalating quickly — appointments, medications, meals, personal care — and he was determined to keep her at home. But the cost to his own wellbeing was undeniable. He was sleep‑deprived, depressed, and beginning to experience cognitive decline himself.

As director of the Referral Education Assistance & Prevention (REAP) program at Seacoast Mental Health Center, which supports older adults and caregivers across New Hampshire in partnership with the CMHC’s across the state, I hear stories like his every week. And his experience is far from unique.

Across the country, 24% of adults are family caregivers. Here in New Hampshire, 281,000 adults provide this essential care, often with little preparation or support. Only 11% receive any formal training to manage personal care tasks — yet they are the backbone of our long‑term care system, helping aging parents, spouses, and loved ones remain safely at home. (AARP, 2025)

REAP provides short‑term counseling, education, and support for older adults, caregivers, and the professionals who support them. We address concerns around mental health, substance use and cognitive functioning. After 21 years working with caregivers, I have seen how inadequate support directly harms families. Caregiving takes a serious toll — emotionally, physically, socially and financially. Many experience depression, chronic stress, and increased risk of alcohol or medication misuse.

In REAP’s own data from 2024:

- 50% of caregivers reported moderate to severe depression

- 29% reported suicidal ideation in the past two weeks

- 25% screened positive for at‑risk drinking

Their responsibilities go far beyond tasks like medication management and meal preparation. They interpret moods, manage behavioral changes, ease emotional triggers, and create meaningful engagement for the person they love. Their world revolves around the care recipient — often leading to isolation, loss of identity, guilt, and ongoing grief.

The statistics reflect what I see every week. Nearly one in four caregivers feels socially isolated. Forty‑three percent experience moderate to high emotional stress. And 31% receive no outside help at all.

Compare that to healthcare workers, who work in teams, receive breaks, have coworkers who step in when overwhelmed, and are trained and compensated for their work. Even with these supports, burnout is common. Caregivers receive none of these protections yet are expected to shoulder the same level of responsibility — alone, unpaid, and unrecognized.

Senate Bill 608 in New Hampshire would finally begin to fill these gaps. The bill provides access to counseling, peer support, training, and caregiver assessment for family caregivers of individuals enrolled in two Medicaid waiver programs: Acquired Brain Disorder (ABD) and Choices for Independence (CFI). These services would address the very needs I see daily.

Professional counseling helps caregivers process the complex emotions of watching a loved one decline or manage the stress that comes with it. Peer support connects them with others navigating similar challenges. Caregiver assessment identifies individual needs before families reach crisis.

When caregivers receive the right support, everyone benefits. The care recipient receives safer, more compassionate care. The caregiver’s health stabilizes instead of deteriorating from chronic stress and neglect. And costly options, which many older adults want to avoid, are delayed or prevented.

There is a direct and measurable link between caregiver training and caregiver wellbeing. The spouse I mentioned earlier is proof. Through REAP, he received education about his wife’s diagnosis, guidance on communication and behavior, and strategies to manage his own stress. Within weeks, his depression decreased from moderate to mild without medication. He was sleeping through the night and thinking more clearly. His frustration with his wife dropped significantly because he finally understood what she was experiencing and how to respond compassionately.

The real question before lawmakers is not whether we can afford SB 608. It is whether we can afford to continue ignoring the needs of those who hold our care system together. In 1970, we had 31 caregivers for every one person needing care. By 2010, that ratio dropped to 7:1. By 2030, it is projected to be 4:1. Our caregiver supply is shrinking while needs continue to grow. Without meaningful support, our systems — healthcare, long‑term care, and community supports — cannot function. (AARP, 2013)

Caregivers don’t ask for much. They want to keep their loved ones safe, comfortable, and at home. They want to stay healthy enough to continue providing care. SB 608 gives them the tools to do exactly that.

I urge New Hampshire lawmakers to support SB 608 and stand with the 281,000 residents who are quietly holding our care system together. We cannot keep waiting until caregivers collapse to offer help. We must provide the support they need now — before the burden becomes too heavy to bear.

Anne Marie Sirrine, LICSW, CDP is a staff therapist and the director of the REAP (Referral Education Assistance & Prevention) program at Seacoast Mental Health Center.

New Hampshire

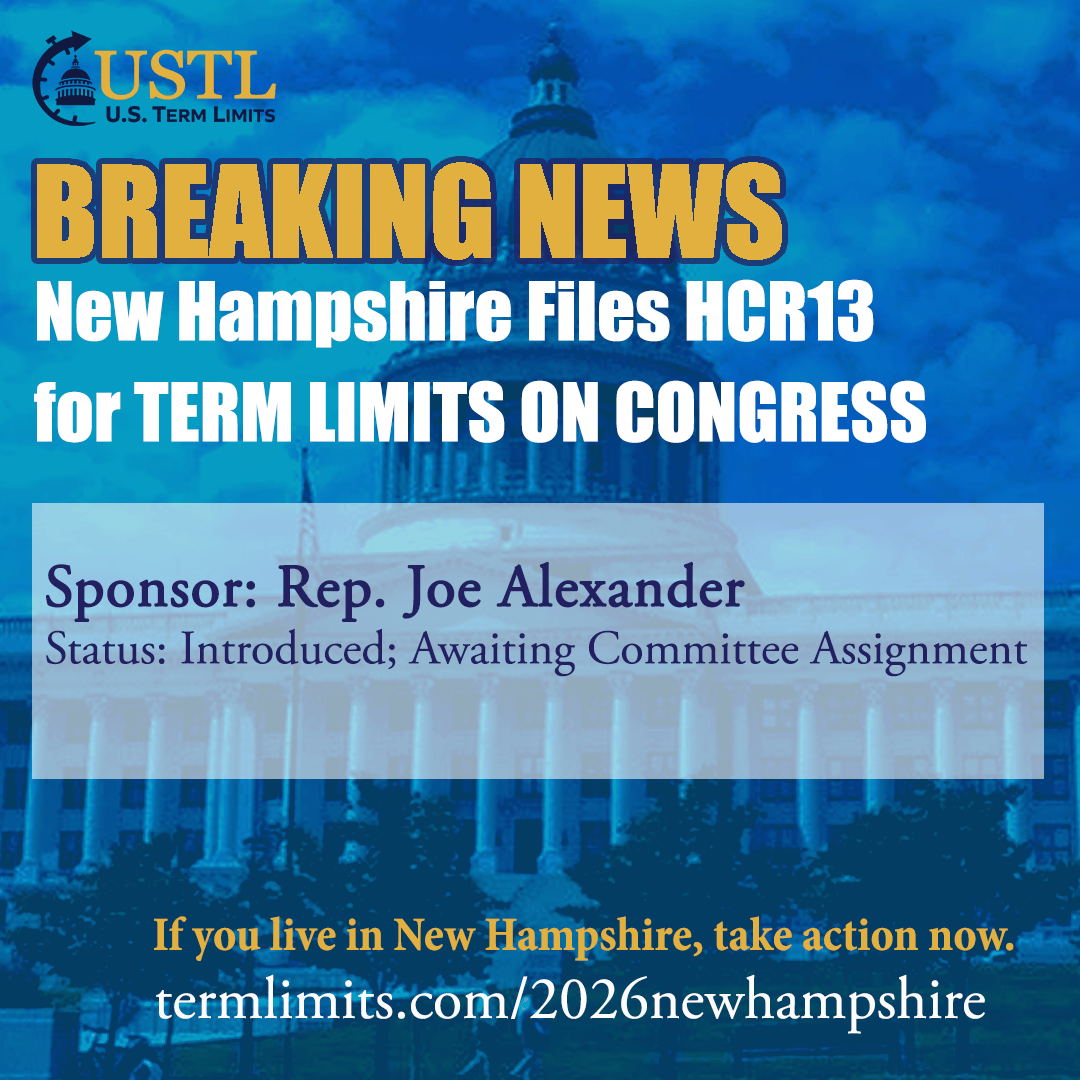

Rep. Joe Alexander Files Term Limits Resolution in New Hampshire – Term Limit Congress

-

Detroit, MI6 days ago

Detroit, MI6 days ago2 hospitalized after shooting on Lodge Freeway in Detroit

-

Technology3 days ago

Technology3 days agoPower bank feature creep is out of control

-

Dallas, TX4 days ago

Dallas, TX4 days agoDefensive coordinator candidates who could improve Cowboys’ brutal secondary in 2026

-

Health5 days ago

Health5 days agoViral New Year reset routine is helping people adopt healthier habits

-

Iowa3 days ago

Iowa3 days agoPat McAfee praises Audi Crooks, plays hype song for Iowa State star

-

Nebraska3 days ago

Nebraska3 days agoOregon State LB transfer Dexter Foster commits to Nebraska

-

Nebraska3 days ago

Nebraska3 days agoNebraska-based pizza chain Godfather’s Pizza is set to open a new location in Queen Creek

-

Missouri3 days ago

Missouri3 days agoDamon Wilson II, Missouri DE in legal dispute with Georgia, to re-enter transfer portal: Source