News

SpaceX’s Falcon 9 launches spy satellites for a second time

News

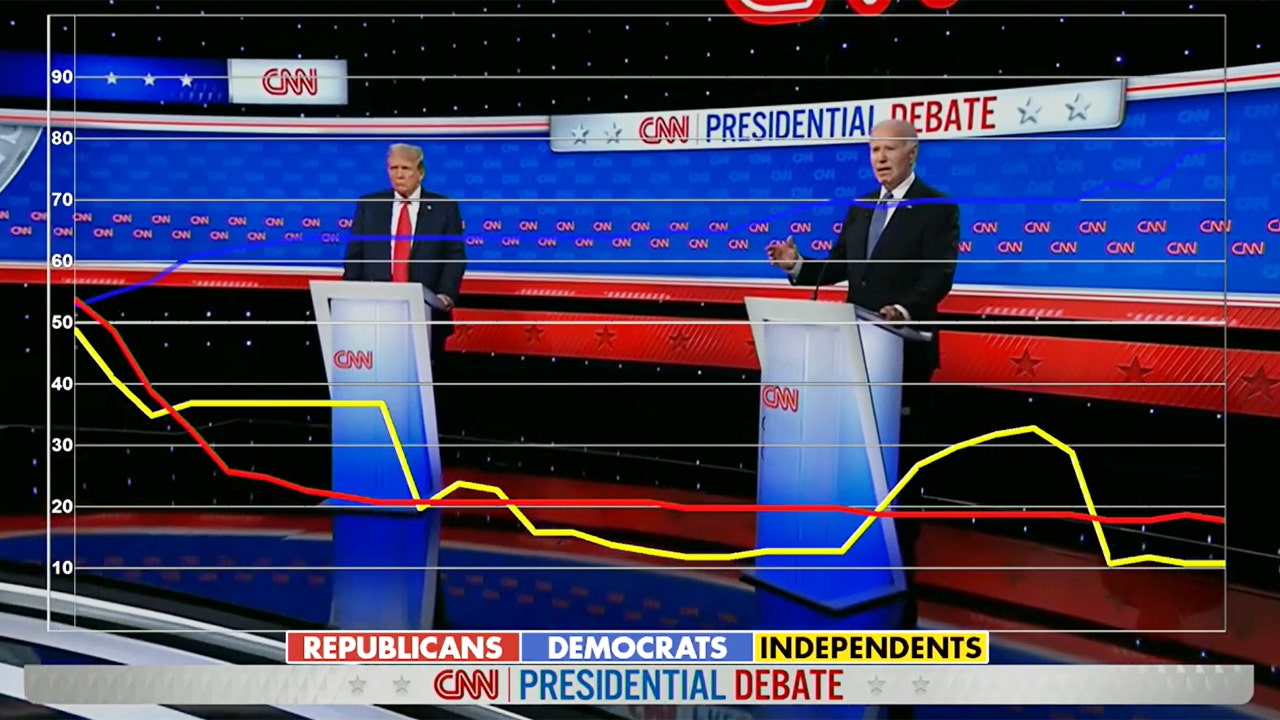

Trump-Biden debate draws smaller audience as voters tune out US election

Unlock the US Election Countdown newsletter for free

The stories that matter on money and politics in the race for the White House

Thursday night’s US presidential debate was watched by 48mn television viewers, a sharp drop from the numbers that tuned in to the clashes between Joe Biden and Donald Trump in the 2020 campaign.

CNN, the Warner Bros Discovery-owned network which hosted the event, said just over 9mn viewers had watched on its own channels, narrowly ahead of Fox News and ABC News, with cable rival MSNBC drawing about 4mn viewers. Another 30mn people tuned in on CNN’s digital channels or YouTube, it added.

The combined television audiences were well below the totals for previous presidential debates, however, extending a pattern of US media outlets reporting less interest in their election coverage this year.

Trump and Biden drew 73mn viewers for their first debate in 2020, while Trump and Hillary Clinton pulled in an audience of 84mn for the opening showdown of their 2016 contest.

With full control over the style, content and format of the debate, CNN inserted rules that are atypical for US political events, such as foregoing a live audience and muting each candidate’s microphones unless it was their turn to speak.

Have your say

Joe Biden vs Donald Trump: tell us how the 2024 US election will affect you

The debate was also a stark departure in tone from last year’s CNN town hall event with Trump, when a studio audience filled with the former president’s supporters prompted comparisons with his raucous rallies. CNN’s own media commentator slammed the town hall as a “spectacle of lies”, and Chris Licht resigned as CNN’s chief executive just a few weeks later.

By comparison, Thursday’s night’s debate was restrained. With microphones muted, there were no shouting matches, and with no audience or press in the room, it was quiet. The moderators played a background role, leaving the debate largely a back-and-forth dialogue between Trump and Biden.

However CNN was criticised for one significant choice: moderators Jake Tapper and Dana Bash largely avoided fact-checking the candidates in real time. The format seemed to favour Trump, who was allowed to make a series of unsubstantiated claims without being challenged during the 90-minute programme.

The debate was a big test for CNN — the network that pioneered the dramatic, ultra-competitive cable news format in the US in the 1980s, but whose audiences have dwindled in recent years. It was easily the biggest moment yet for CNN chief executive Sir Mark Thompson, who took over as leader of the channel last year and has been tasked with turning around its business and restoring its brand.

CNN landed the sponsorship of the debate in May, beating out competitors including Fox News. The network seized on the moment, promoting the event heavily and forcing its rivals, who simultaneously broadcast the debate, to display CNN’s logo prominently on their screens.

The event was unique for a number of reasons. It was the first presidential debate in decades that was not organised by an independent commission, after Biden and Trump chose to bypass the tradition. It was also scheduled far earlier than usual in the election cycle. In previous years, the initial match-ups between presidential candidates took place in September or October.

CNN has a fraught history with Trump, who frequently attacked the channel during his presidency. But on Friday morning, the Trump campaign blasted an email out to his supporters titled: “I love CNN . . . Because they gave me the opportunity to wipe the floor with Joe Biden.”

News

Supreme Court denies Steve Bannon's plea to stay free while he appeals

Steve Bannon, former adviser to President Donald Trump, and attorney Matthew Evan Corcoran, depart the E. Barrett Prettyman U.S. Courthouse on June 6, 2024 in Washington, D.C.

Kent Nishimura/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Kent Nishimura/Getty Images

The U.S. Supreme Court rejected an appeal by Steve Bannon, the right-wing podcaster and former Trump White House aide, to remain free while his case goes through the appeals process.

“The application for release pending appeal presented to The Chief Justice and by him referred to the Court is denied,” the court said in a one-sentence order.

Bannon now has a deadline to report to a federal prison in Connecticut July 1. He must serve time after refusing to comply with a congressional investigation into the siege on the U.S. Capitol.

A federal jury in Washington, D.C., convicted Bannon two years ago on two criminal contempt charges, for defying subpoenas for documents and testimony from the House Select Committee investigating the events of Jan. 6, 2021.

Bannon successfully delayed his four-month prison sentence for years, as appeals wound through the courts. But his luck ran out in May, when a federal appeals court unanimously rejected his claims.

Bannon is the second Trump-era official ordered to serve prison time for flouting demands from Congress. Trump trade adviser Peter Navarro reported to a prison in Florida in March, after Chief Justice John Roberts refused to intervene in the case.

Both men cast their disputes with Congress as challenges to the Constitution’s separation of powers, but judges found no evidence that Trump had formally asserted executive privilege to block their cooperation with lawmakers.

Bannon had tried to argue at his trial that he had relied on advice from his lawyer, and therefore lacked the intent to “willfully” violate the contempt law. A judge foreclosed that defense based on court precedent, but raised significant questions about it — questions that Bannon cited in a June 21 petition to the Supreme Court.

“Mr. Bannon relied in good faith on his attorney’s advice not to respond to a subpoena issued by a House Select Committee until executive privilege issues were resolved—as they had been on three prior occasions when Mr. Bannon had agreed to testify after President Trump’s counsel had asserted executive privilege,” his lawyers wrote.

Bannon, who has been a vocal supporter of Trump’s bid to regain the White House later this year, may now be incarcerated on those misdemeanor charges through the election in November.

He’s separately fighting fraud, money laundering and conspiracy charges in New York state court over an alleged scheme to defraud donors to a charity that aimed to build a wall along the southern border. That case is scheduled for trial later this year.

Trump granted Bannon a full pardon from federal charges related to We Build the Wall in January 2021, shortly before he left the White House. Presidents lack power to issue pardons for state crimes.

News

Psychiatrist Bessel van der Kolk: ‘When trauma becomes your identity, that’s a dangerous thing’

The sound of piano music floats among the white-linened tables of the Red Lion Inn’s dining room as Bessel van der Kolk declares the end of humanity.

“We are doomed as a species!” says the 80-year-old psychiatrist, perhaps the most influential of the 21st century, leaning towards me across a half-empty glass of Sauvignon Blanc.

“We can’t do it! We can’t use our rational brains,” he continues, with the vigour of a much younger man. “Climate change. It’s very serious stuff! . . . Are you still flying?”

He jabs a finger in my direction. I confess that I am.

“You know you shouldn’t!” he says in a thick Dutch accent, his bearded face creasing with affable frustration.

Over the past few hours in this corner of rural Massachusetts, I’ve learnt that the energetic octogenarian is not short on strong views. We have already touched on the militant group Hamas (“What the hell were you doing?”), and will later get on to Sigmund Freud (“a bit of an egomaniac”) and Brexit (“You guys fucked that one up!”).

But van der Kolk has built a storied career on stubbornly staking out contentious positions. One of the first researchers to study post-traumatic stress disorder in Vietnam war veterans in the 1980s, he spent the ensuing decades fighting a tide of indifference in the academic community over the psychological impact of the worst horrors that can befall human beings.

In recent years, his 2014 masterwork The Body Keeps the Score has become an improbable sensation. Buoyed by a groundswell of popular interest in trauma and psychology in the wake of the pandemic, the dense, scientifically rigorous text has become a latent, runaway success, spending nearly 300 weeks on the New York Times bestseller list.

“It feels odd,” he says of his elevation to the internet’s favourite therapist. “Because it’s a sort of external persona that you become, but of course I am unchanged. I’m still the same old flawed creature I’ve always been.”

The 18th-century Red Lion Inn is a curiously tranquil place to be meeting this archaeologist of nightmares. As I await van der Kolk’s arrival earlier that afternoon, the faint smell of potpourri wafts from among chintz armchairs in the lobby beyond. Above my head, I notice absent-mindedly, the ceiling beams host an impressive collection of antique teapots.

“You flew all the way here from London?” he says a few minutes later, settling into his chair and scrutinising me through wire-rimmed glasses. “This had better be a good lunch!”

The thesis of van der Kolk’s book, and indeed much of his life’s work, is that horrifying experiences leave an imprint on the mind and body that prevents them from being properly consigned to the past. As a result, traumatised people become stuck, like mosquitoes in amber, frozen in the moment of catastrophe.

“You and I, what will we remember of this lunch a year from now?” he says as we each order a glass of white wine and look out over the thick forest carpeting the surrounding Berkshire mountains. “Maybe what we ate. Maybe something else. But we won’t have nightmares about it.

“But if something terrible were to happen from now on, sitting at a table like this may become a trigger for me,” he continues. “Somebody who looks like you. The sensation becomes the trigger for the emotional experience.”

The book describes case studies of unthinkable horrors. A woman wakes up during surgery to feel a scalpel lacerating her abdominal organs; a married couple miraculously survive an 87-car pile-up on a Canadian highway.

But while these extraordinary events are edge cases, van der Kolk argues that it is “extremely common” to experience trauma. “I’m about as privileged as you get, and my life is still hard,” he says, in a whispery intonation that frequently reminds me of David Attenborough. “We all have people die on us, people disappear on us. It’s challenging.”

A waiter arrives with a goat’s cheese salad for me, adorned with candied walnuts. Van der Kolk, who has declined a starter, sips his wine contentedly as I chomp hastily through pear and radicchio.

Menu

The Old Red Lion

30 Main Street, Stockbridge MA 01262

Glass Sauvignon Blanc x4 $56

Goat’s cheese salad $15

Steak frites $40

New England lobster roll $36

Total (incl tax and tip) $177.66

We turn to his childhood in the Netherlands in the aftermath of the second world war. Van der Kolk says his father, despite being jailed by the Nazis for his pacifism, was an authoritarian at home. “I said, ‘Dad, you were in a Nazi concentration camp, and here you are running a house like a concentration camp!’” he says.

The impact of “adverse childhood experiences” is a major thread of van der Kolk’s work, and explains why so many people bear the hallmarks of traumatic stress, from depression to addiction. The Body Keeps the Score argues that child abuse constitutes the “gravest and most costly public health issue in the United States”.

In a landmark 1998 US study cited in the book, more than a quarter of respondents said they had been physically abused as children. It also found that people who had four types of negative early-life experience — such as abuse, neglect or family dysfunction — were seven times more likely to become alcoholics than those who had none.

“Everybody who gets hurt at home tries to pretend it’s normal to everybody else,” says van der Kolk gravely of the child’s evolutionary impulse to protect the bond with their caregiver, even if that person is causing them harm. “You’re not going to tell your classmates that something [bad] happens to you.”

A waitress deposits a Subway-sized lobster roll in front of van der Kolk and hands me a plate of steak so large that its accompanying frites are spilling on to the table.

A few weeks before our meeting, the social psychologist Jonathan Haidt published the much-discussed The Anxious Generation, which links the recent rise in adolescent mental-health problems to the increased use of smartphones among young people.

“Very important book I think,” says van der Kolk, attacking his lobster with his knife and fork. “This huge flag that he’s raising, I don’t know what the hell we’re going to do about it.”

Like Haidt, van der Kolk argues that the rise of screen-based communication, propelled by the pandemic lockdowns, has degraded the experience of human interaction. “On a screen, you don’t work for it, you get a reward without reciprocity,” he says. “That’s huge. You don’t have the sense you’ve done anything, any sense of accomplishment. You get cheap rewards for minor actions, and it’s meaningless.”

The pandemic also accelerated a shift in the way people think about themselves, as a social-media-driven focus on identity fused with concerns about our collective mental health. The result has been a growing cultural preoccupation with trauma — a word that is invoked everywhere from university campuses to TikTok.

“Did you ever take a history course?” says van der Kolk of the popular argument that we are living in an unusually traumatic era. “Read about the French Revolution?”

For van der Kolk, there is a strange irony that the concept he worked so hard to inscribe into the academic canon has become a mainstay of online culture.

“The moment I saw trauma, it grabbed me,” he says, remembering the day in 1978 when he first encountered a Vietnam veteran with PTSD. But as he pursued the subject further, he says, “My colleagues would say, ‘What’s this trauma bullshit? After you croak, no one will ever talk about trauma again.’”

Despite the popularity of The Body Keeps the Score today, he says that the academic community remains fractured in its understanding of the mechanisms and treatment of trauma. (It has also battled institutional dysfunction: in 2018, van der Kolk was fired as medical director of the Trauma Center in Massachusetts over what was characterised as an allegation of bullying, which he denies, saying he was removed to “mitigate . . . legal liability” over the actions of another employee.)

“Maybe from the outside, you see people have adopted [the concept of trauma] . . . I don’t see it in the major academic institutions,” he says. “It’s curious how widely the book is read.”

We are meeting as the conflict between Israel and Hamas has killed more than 30,000 people, and is threatening to spill over into a broader regional war.

I ask if he views such events through the lens of trauma — of each side reacting not just to the immediate demands of warfare but also to years, even generations, of pain.

“I get both stories,” he says, referring to the fraught histories of Israel and Palestine, “and they’re both horrible trauma stories . . . [But] we all come from generations of trauma. It’s no excuse. When trauma becomes your identity, that’s really quite a dangerous thing.”

“What’s appalling to me is that ideology is trumping facts,” he says, noting that he has faced accusations of antisemitism for making public reference to the Palestinian death toll without mentioning the Israelis killed on October 7.

“It’s tearing America apart,” he says. “This may just have a disastrous result on our election.”

Van der Kolk, who emigrated to the US in 1962 and now lives with his wife in the nearby Berkshire Hills, appears to retain a fondness for his home continent. He calls the European Union “the greatest miracle of our time”. The American healthcare system, by contrast, he describes as “a disaster”.

“There is something about this high-risk living in America that really brings out the best and the worst in people,” he says thoughtfully. “If I’d stayed in Holland, I would’ve become chronically depressed.

“In America,” he adds with a chuckle, “I’m chronically anxious.”

The dining room has thinned out and the chattering of lunchtime guests has dwindled to a low hum. A waitress removes my long-finished plate and asks if we’d like a second glass of wine as van der Kolk picks at the last of his lobster.

“I’ll get another,” he says brightly, after some consideration.

If the first half of van der Kolk’s book is concerned with the damage that our existence can inflict on us, the second proposes solutions for how we might be healed. Contentiously in this golden age of talk therapy, he is sceptical of the power of language to treat psychological injuries.

“These are habitual, visceral reactions,” he says. “Understanding why doesn’t rewrite the experience . . . Talking about why my tennis game was off is not always useful. I need to go back on the court and practise again.”

He is similarly lukewarm on mainstream pharmaceutical interventions for depression and anxiety, such as Prozac and other selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, or SSRIs. “It’s: let me give you a pill, and stop being a pain in the ass!” he says of psychiatrists’ tendency to prescribe drugs that simply block out psychological pain.

Instead, he believes that the brain can be more durably rewired to properly integrate traumatic experiences into memory, using more experimental treatments such as MDMA-assisted therapy.

“In psychedelics, it’s as magical an exploration of the world as you can have,” he says, with evident enthusiasm. “It’s entering a territory you don’t know anything about, and stuff comes up that you didn’t know was living inside of you.

“You go there and part of you experiences it,” he continues, “and part of you observes yourself experiencing it, and the experience is very much like, ‘Oh my God, that’s what I went through.’”

He argues that the clue to healing may lie as much in the body as the mind. Yoga can produce “quite dramatic” results in traumatised people, he says, noting that he recently visited a prison that had implemented a programme for inmates based on his book.

“A goddamn healing environment in a maximum-security prison?” he says. “That’s stunning.”

Van der Kolk’s book contains frequent admissions that the mechanisms behind many trauma treatments, some of which border on the bizarre, are not fully understood. (He is particularly enthusiastic about eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing, or EMDR, in which patients move their eyes from side to side while remembering traumatic events.)

I ask if we will look back on such methods as laughably rudimentary in years to come, in the same way that we see bloodletting and lobotomies today. “I hope so! . . . It’s the nature of the beast, we always cling to stuff that to other people sounds ridiculous,” he says. “But I hope that 50 years from now we’ll be laughing at ourselves.”

As we finish the dregs of our wine, I note that van der Kolk’s continued enthusiasm for his field is impressive at an age when most people would be enjoying a quiet retirement. “What do I do?” he says incredulously. “Learn how to play golf?”

He suddenly grabs his phone in alarm. “Oh my gosh, it’s almost three o’clock. Oh boy! Who did I stand up?”

He tells me he has a patient to see. I call for the bill. We shake hands, say our goodbyes, and he’s off into the forest.

India Ross is the FT’s deputy news editor

Find out about our latest stories first — follow FT Weekend on Instagram and X, and subscribe to our podcast Life & Art wherever you listen

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoNYC pastor is sentenced to 9 years for fraud, including taking a single mom's $90,000

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoRead the Ruling by the Virginia Court of Appeals

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoTracking a Single Day at the National Domestic Violence Hotline

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoOrbán ally-turned-rival joins EPP group in European Parliament

-

Fitness1 week ago

Fitness1 week agoWhat's the Least Amount of Exercise I Can Get Away With?

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoSupreme Court upholds law barring domestic abusers from owning guns in major Second Amendment ruling | CNN Politics

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoTrump classified docs judge to weigh alleged 'unlawful' appointment of Special Counsel Jack Smith

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoSupreme Court upholds federal gun ban for those under domestic violence restraining orders

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/pmn/YE6IIODUERBWVOQEYG5BI3T5CE.jpg)