North Dakota

‘Their spirits are still here’: Tribe, state to search for remains at North Dakota boarding school

Editor’s notice: That is the fifth story in an occasional collection on Native American boarding colleges and their affect on the area’s tribes.

FORT TOTTEN, N.D. — On a cloudy October morning, Denise Lajimodiere walked by way of brambles and tall grass along with her eyes to the bottom.

Consulting a photograph from the Eighties, the scholar scanned the prairie terrain close to the Fort Totten State Historic Website for small, tan boulders that would mark graves lengthy hidden from view.

After stumbling throughout one, she grabbed a plastic baggie of tobacco from her coat pocket, held a pinch tight in her left fist and stated a prayer for the our bodies which will have been buried beneath her ft greater than a century in the past.

Historic website workers imagine the boulders could possibly be the vestiges of a cemetery for U.S. troopers buried within the mid-1800s. Lajimodiere thinks the gravesite may additionally comprise the stays of Native American kids who died whereas attending a boarding college on the former army submit.

“We all know their spirits are nonetheless right here,” Lajimodiere stated solemnly whereas strolling the positioning on the Spirit Lake Reservation in northeast North Dakota.

Following

final 12 months’s discovery

of graves possible belonging to Indigenous kids who attended Canadian boarding colleges, america has begun to reckon with the concept that the stays of scholars could possibly be buried in unmarked graves close to former American boarding colleges.

Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Chairman Jamie Azure is sort of sure that’s the case at Fort Totten.

Azure has heard dozens of tales about kids from his tribe who died or disappeared beneath unsure circumstances at boarding colleges like Fort Totten. He hopes an investigation into the positioning will convey closure for households nonetheless in search of solutions generations later.

The Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa and the State Historic Society of North Dakota lately agreed to companion in a seek for the stays of former Fort Totten college students. Spirit Lake Chairman Doug Yankton stated he welcomes the investigation on his tribe’s land.

“The whole lot simply provides up in my thoughts that we’ll discover unmarked graves, and we’ll discover tribal members,” Azure stated.

The U.S. Division of the Inside

launched a report in Might

that recognized 408 federal boarding colleges and examined the federal government’s function in forcibly taking Native American kids away from their households to boarding colleges geared toward assimilating them into white tradition.

The division’s investigation discovered “marked or unmarked burial websites” at 53 boarding college websites however didn’t disclose their areas to stop grave robbing. The company expects to seek out extra burial websites at boarding colleges as its investigation continues.

Lajimodiere, an enrolled Turtle Mountain citizen whose father and grandfather attended Fort Totten, discovered proof that at the very least 13 Native American boarding colleges existed in North Dakota.

Spiritual orders together with the Catholic Church ran a number of the colleges, however the federal authorities operated Fort Totten and a handful of different establishments.

Fort Totten was by far the most important within the state, and at its peak enrollment of greater than 500 college students within the 1910s, was one of many largest on-reservation colleges within the nation.

Interviews, inner paperwork and

Lajimodiere’s findings

reveal Fort Totten was a college with a tradition of systemic abuse and neglect of kids, however no direct proof has been discovered to counsel college students who died on the college had been buried on or close to the property.

If the search locates graves on the website and identifies the stays as former college students, it might enable the tribe to present its members the correct burials they had been denied so way back, Azure stated.

“The tip purpose is simply to guarantee that if we’ve any Turtle Mountain members which were misplaced alongside the best way, we make rattling positive that we’re in a position to convey them dwelling in a cultural and conventional and respectful method,” Azure stated.

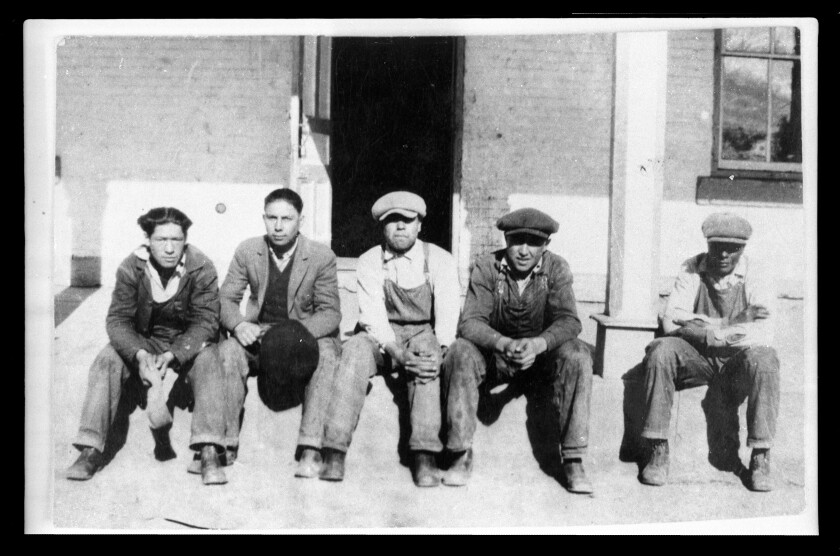

Dave Samson / The Discussion board

From elimination to assimilation

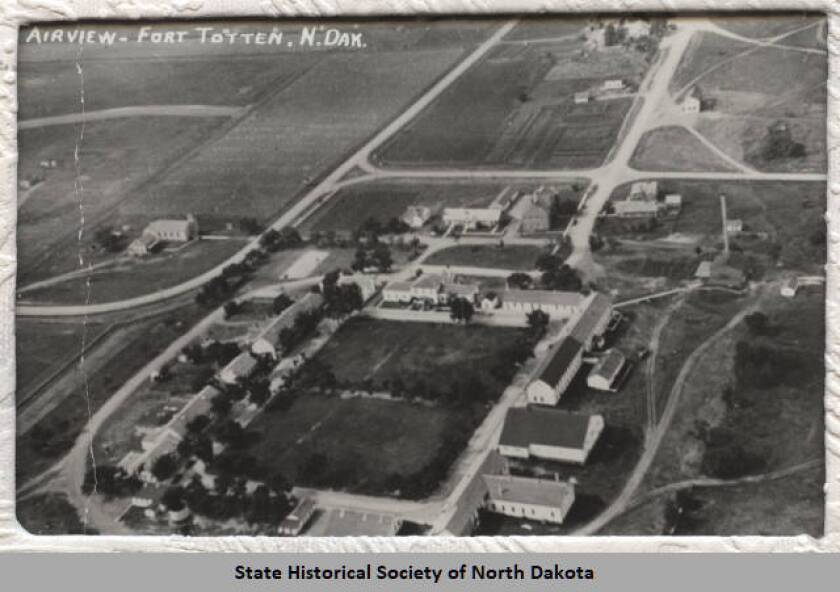

For longer than North Dakota has been a state, 16 brick buildings have stood in a neat rectangle not removed from the southern shores of Devils Lake.

To some, the enduring constructions on the

Fort Totten State Historic Website

signify the proud legacy of the nation’s army and the area’s early frontier settlers.

However for a lot of Native People with roots within the higher Midwest, Fort Totten serves as a bodily reminder of the abuse they and their ancestors endured as kids.

American troopers based the outpost in 1867 — the identical 12 months Sisseton and Wahpeton Sioux leaders signed a treaty establishing the Fort Totten Indian Reservation (later renamed the Spirit Lake Dakota Reservation). A flood of white settlers within the 1800s

compelled the 2 Sioux bands

from their ancestral homelands in modern-day Minnesota.

The federal authorities tasked the troops stationed on the fort with settling and policing the reservation and defending journey and commerce routes, based on

historian Michael McCormack.

On the time, officers in Washington together with President Ulysses S. Grant had begun to shift their technique on Native People from elimination to assimilation — a mission that needed to begin with the youngest technology.

The reservation’s federal Indian agent, William Forbes, recruited the Gray Nuns, an order of Catholic sisters from Montreal, to run a “handbook labor college,” historian James Carroll writes within the e-book “Fort Totten Army Publish and Indian College.”

The establishment opened in 1874, and had greater than 50 Sioux college students by the tip of the varsity 12 months. Along with laborious labor, the curriculum included some primary educational and spiritual instruction — a mixture that aligned with the U.S. Workplace of Indian Affairs’ philosophy for “civilizing” Native American kids, Carroll writes.

On New 12 months’s Eve of 1890, the army turned over Fort Totten to the Workplace of Indian Affairs for the aim of making an on-reservation Native American boarding college within the picture of

Carlisle Indian Industrial College

in Pennsylvania — an establishment that aimed to strip Native People of their language, tradition and household ties.

The Fort Totten Indian Industrial College opened on the former army outpost on Jan. 19, 1891, beneath Superintendent William Canfield’s management.

State Historic Society of North Dakota picture

Indian Affairs officers allowed the Gray Nuns to proceed instructing as a semi-autonomous division throughout the federally run college in what Carroll describes as “an uncommon association.”

Federal Indian brokers withheld rations and monetary assist from mother and father who didn’t willingly enroll their kids on the college, Carroll writes.

Most members of the native Devils Lake Sioux Tribe (now the Spirit Lake Tribe) most popular to ship their kids to the Gray Nun division and rejected the fort college, Carroll writes. The vast majority of the scholars on the fort college within the first 20 years got here from the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa’s reservation, which lies about 70 miles to the northwest.

Canfield’s 11 years on the helm of the varsity had been marked by workers brutality, rampant illness, frequent runaways and extreme handbook workloads.

And whereas it stays a thriller whether or not kids had been buried on or close to the positioning of the varsity, there isn’t a doubt college students died whereas attending Fort Totten.

College officers reported three to 5 scholar deaths every year between 1891 and 1902, with causes together with measles, meningitis and smallpox, based on Carroll and modern sanitary information. The entire reservation suffered from excessive mortality charges on the time, however the deaths on the college gave many mother and father a motive to maintain their kids from attending.

In a 1900 assembly with a federal boarding college supervisor, adults from the reservation reported appalling abuses inflicted on Fort Totten college students by Canfield’s administration.

Youngsters had been mercilessly whipped, denied meals for days, handcuffed or put in straightjackets for tardiness and different minor rule violations, based on assembly information. An observer additionally referred to the Gray Nuns as being overly strict and “utilizing a picket snap to present indicators,” Carroll writes.

Although a college in identify, Fort Totten beneath Canfield extra carefully resembled a piece camp for Native American youth. Reservation residents complained that the backbreaking labor of carrying rocks, reducing ice and chopping wooden got here with no instructional worth and risked harming the youngsters.

College students steadily ran away — a commonality shared with boarding colleges throughout the nation — and two boys drowned in Devils Lake whereas fleeing Fort Totten, Carroll writes.

Federal officers stood by Canfield regardless of discovering proof of abuse. The superintendent didn’t lose his job till 1902 when he tried to put in his spouse as the varsity’s head matron, an act of nepotism that upset different workers.

State Historic Society of North Dakota picture

Underneath the course of a alternative superintendent, Fort Totten turned the most important on-reservation boarding college within the nation with greater than 340 college students, Carroll writes.

An area Indian agent reported that the situation of the varsity had tremendously improved after Canfield departed, however college students nonetheless suffered by way of measles outbreaks from 1904 to 1906.

Amid monetary difficulties, college officers regarded to extend enrollment, which introduced in greater federal allocations and extra kids to work handbook labor jobs that sustained the establishment.

By 1917, greater than 530 college students principally from the Dakotas and Montana attended the varsity. The extraordinarily tight dwelling quarters had a unfavorable affect on the scholars’ well being, Carroll writes.

The varsity quickly shut down from 1917 to 1919 on account of cash troubles, however a couple of years after it reopened, nationwide curriculum modifications put a better emphasis on classroom and vocational studying.

A 1928 federal report dropped at mild the most important deficiencies of Native American boarding colleges, and finally led to the shuttering of the fort college in 1935. For the following 5 years, the positioning turned a sanatorium for kids with tuberculosis.

Lots of the college students transferred to day colleges or the Gray Nuns’ Little Flower boarding college, which opened a number of miles from the fort in St. Michael in 1929. Former college students of the Catholic establishment recall that the nuns had been imply and abusive to college students.

Alvina Alberts, who attended the varsity from the age of 5, stated in

a 1993 interview with College of Mary

researchers that the nuns hit college students with the sharp-edge of a ruler, including “I had damaged bones in my arms that I didn’t learn about till I used to be in my 50s.”

The fort later turned a day and boarding college for Native American kids in 1940. By then, the curriculum mirrored that of most public colleges within the state, Carroll writes. The varsity closed for good in 1959, and the federal authorities turned over the positioning to the state.

At present on the Fort Totten State Historic Website, vacationers can take self-guided excursions by way of a number of the outdated buildings and purchase souvenirs at a present store.

By far essentially the most well-maintained buildings are a prairie-themed mattress and breakfast and a memorial-like museum devoted to the Lake Area Pioneer Daughters.

A handful of show boards and plaques describe the Native American boarding college that after operated on the fort, however the website’s army historical past is introduced as the primary attraction.

‘I cannot discuss in class’

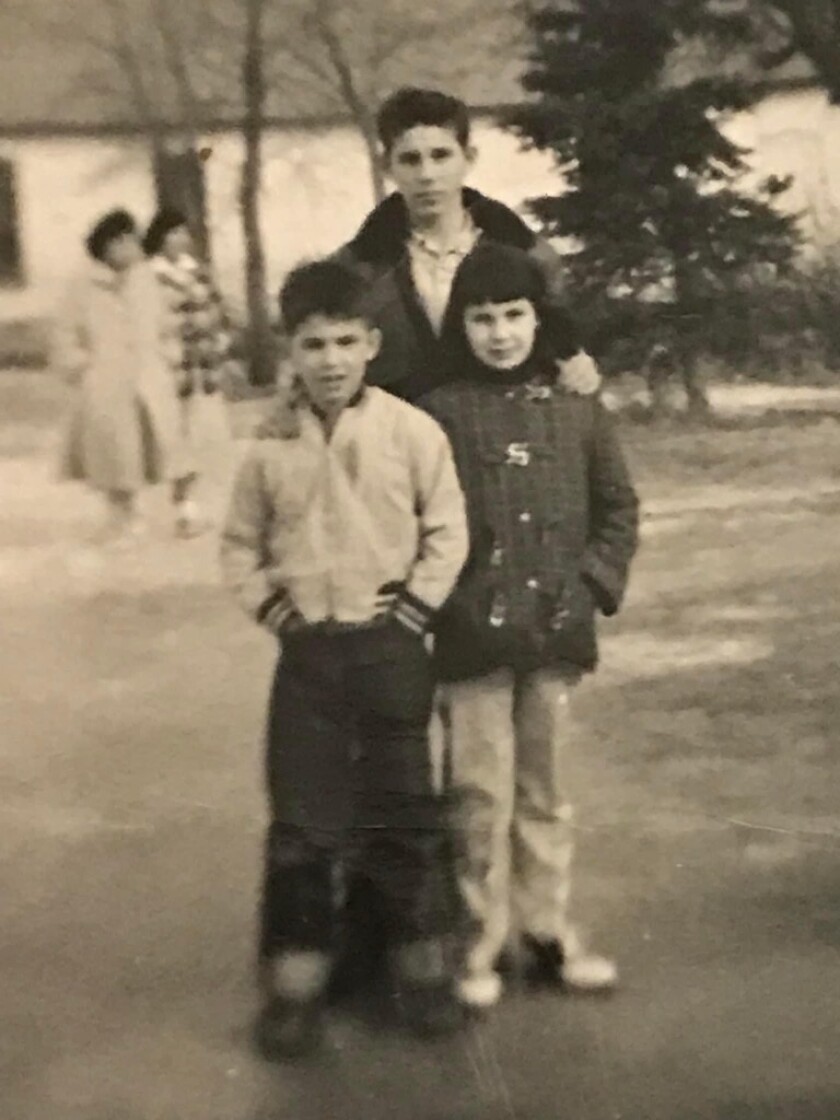

When Ramona Klein, 74, thinks again on her time attending Fort Totten from 1954 to 1958, two emotions stick out in her thoughts: loneliness and starvation.

Klein, when she was about 5 years outdated, lived in a two-bedroom dwelling with out electrical energy in Belcourt on the Turtle Mountain Reservation. Neither of her mother and father had a gradual earnings, and Klein remembers her stomach was always empty.

Then in 1954, she was despatched to Fort Totten together with 5 of her siblings.

Klein’s undecided if her mother and father had been coerced into having their kids attend boarding college or if it was her mother and father’ last-ditch effort to look after them. She additionally doesn’t know whether or not they had been conscious of Fort Totten’s poor fame.

“I don’t actually know if I might say it was a selection for us to go to boarding college in that method. It wasn’t my selection. I used to be a toddler,” Klein stated. “However even for my mother and father, is it actually a selection in case your children are going to starve and freeze?”

Klein left her Belcourt dwelling for the primary time in her life when she was 6 years outdated. She and 5 of her siblings boarded a inexperienced college bus and journeyed southeast to Fort Totten.

“All of the buildings appeared so massive and unusual,” Klein recalled.

The youngsters had been introduced right into a room the place the women got inexperienced plaid clothes. A matron reduce off her lengthy black hair, making it right into a bowl-like reduce. Klein remembers being led in a line — the necessary formation for the youngsters to go from constructing to constructing — and strolling throughout the army sq. to the woman’s dormitory.

Searching the window from her dormitory, she remembers craving to see her mother and father strolling towards the varsity to convey her dwelling.

“I’d say, ‘Possibly tomorrow.’ There was at all times, at all times that longing,” she stated.

Submitted picture

Klein remembers her schooling being nearly nonexistent. She doesn’t keep in mind the topics that had been taught, solely the punishments she obtained.

She recalled a number of events when she needed to write the phrase “I cannot discuss in class” 1,500 occasions in a row for speaking out of flip in school.

Every time college students misbehaved or stole meals from the kitchens due to starvation, lecturers beat the youngsters with a picket paddle crudely named “the board of schooling,” she stated.

Klein now has a doctorate in instructional management and has labored throughout all 50 states. She typically talks about Fort Totten, recalling how her time there greater than 65 years in the past impacts her life at present. She nonetheless has flashbacks after she speaks about her boarding college expertise.

Her knees are stiff and ache often, which she believes stems from being compelled to kneel on a broomstick deal with at any time when she spoke out of flip or misbehaved.

State Historic Society of North Dakota picture

Klein is used to getting incredulous seems to be when she tells individuals about her experiences as a toddler. She stated many imagine that those that attended Native American boarding colleges died way back.

“Folks are likely to assume that these of us who skilled it will not be dwelling, nevertheless it’s dwelling historical past,” Klein stated.

The tribal and state officers dedicated to looking the world across the fort for attainable gravesites perceive it’s an extended and costly course of with little precedent in North Dakota.

The state Historic Society approached Turtle Mountain about inspecting the positioning for unmarked graves throughout the final two months, and the search stays in its nascent levels.

Andy Clark, the Historic Society’s archaeology and historic preservation director, stated the investigation of the Fort Totten website will loosely observe a mannequin set at Kamloops Indian Residential College in British Columbia, Canada, the place

an anthropologist found about 200 potential graves.

State researchers and archaeologists should first slim down the huge space across the fort, Clark stated.

This preliminary step will lean on outdated maps and paperwork and the oral histories compiled by Lajimodiere to pinpoint the most definitely areas for burial websites, Clark stated.

Dave Samson / The Discussion board

Historic aerial pictures give archaeologists an opportunity to see what the bottom regarded like a long time in the past — doubtlessly way back to the Thirties. Observing how land use has modified over time permits them to see areas the place people might have disturbed the earth.

Clark stated archaeologists will then use “non-destructive strategies” like drones to seize high-resolution pictures of the land which may reveal any “anomalies,” together with depressions within the floor.

If the drone pictures reveal areas worthy of additional investigation, the following steps could be performing surveys at floor degree and trying to recuperate any stays, although Clark expects there must be intensive discussions earlier than shovels hit grime because of the “delicate nature” of excavation.

Figuring out any stays could be one other main problem, Azure stated.

For now, the state will deal with the prices related to the investigation, stated Historic Society Director Invoice Peterson.

Jeremy Turley / Discussion board Information Service

Azure stated he plans to succeed in out to North Dakota’s congressional delegation concerning the federal authorities taking over a number of the monetary burden of the investigation and any attainable repatriations, however he stated the tribe gained’t “be held up with forms” if it doesn’t discover prepared companions in Washington.

Turtle Mountain and the Historic Society have lately begun discussing timelines for finishing steps of the investigation, however they haven’t but established a agency schedule, Clark stated.

Azure stated the tribe is in an odd place the place it hopes to seek out no unmarked graves close to Fort Totten, nevertheless it needs to convey a sense of finality to households with kin who by no means got here dwelling from boarding college.

If the tribe does find the stays of Turtle Mountain kids as Azure expects, the chairman stated he needs to convey them again to the reservation and provides them a conventional burial with a spirit hearth that might enable them to “go onto that subsequent degree of their journey.”

“Plenty of these kids weren’t given that chance to go onto that subsequent degree, so it’s not solely the households getting closure, nevertheless it’s the Turtle Mountain members who’re misplaced that must be introduced again,” Azure stated.

In regards to the “Buried wounds” collection

In Might 2021, an anthropologist found unmarked graves possible belonging to 200 kids on the grounds of the Kamloops Indian Residential College in Canada. This disturbing discovering drew consideration to america’ function in forcibly assimilating 1000’s of Indigenous kids by way of its personal boarding college insurance policies.

From 1819 and thru the Nineteen Sixties, the U.S. authorities oversaw insurance policies for greater than 400 American Indian boarding colleges throughout the nation, together with at the very least 13 in North Dakota. Lots of the kids who attended colleges in North Dakota and elsewhere had been taken from their properties in opposition to their will, stripped of their tradition and abused bodily, sexually and psychologically.

Little analysis has been carried out on precisely what number of colleges existed within the U.S. and the extent to which the federal authorities knew concerning the situations of every college. The U.S. Division of the Inside beneath Secretary Deb Haaland is investigating the historical past and legacy of federally run boarding colleges.

The Discussion board has launched its personal investigation into boarding colleges in North Dakota and different elements of the nation by interviewing survivors, reviewing public information and exploring the affect these colleges nonetheless have on North Dakota’s Indigenous inhabitants at present.

The primary installment within the collection concerning the Sisseton and Wahpeton kids who died on the Carlisle Indian Industrial College

will be discovered right here.

The second installment concerning the Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara kids who died on the Carlisle Indian Industrial College

will be discovered right here.

The third installment about Christian denominations reckoning with their function in Native American boarding colleges

will be discovered right here.

The fourth installment about delays in repatriating the stays of two Sisseton and Wahpeton boys from the previous Carlisle Indian Industrial College

will be discovered right here.

North Dakota

European potato company plans first U.S. production plant in North Dakota

Screen Capture: https://agristo.com/timeline

Agristo, a leading European producer of frozen potato products, is making big moves in North America. The company, founded in 1986, has chosen Grand Forks, North Dakota, as the site for its first U.S. production facility.

Agristo has been testing potato farming across the U.S. for years and found North Dakota to be the perfect fit. The state offers high-quality potato crops and a strong agricultural community.

In a statement, Agristo said it believes those factors make it an ideal location for producing the company’s high-quality frozen potato products, including fries, hash browns, and more.

“Seeing strong potential in both potato supply and market growth in North America, Agristo is now ready to invest in its first production facility in the United States, focusing on high-quality products, innovation, and state-of-the-art technology.”

Agristo plans to invest up to $450 million to build a cutting-edge facility in Grand Forks. This project will create 300 to 350 direct jobs, giving a boost to the local economy.

Agristo is working closely with North Dakota officials to finalize the details of the project.

Negotiations for the plant are expected to wrap up by mid-2025.

For more information about Agristo and its products, visit www.agristo.com.

Agristo’s headquarters are located in Belgium.

North Dakota

Audit of North Dakota state auditor finds no issues; review could cost up to $285K • North Dakota Monitor

A long-anticipated performance audit of the North Dakota State Auditor’s Office found no significant issues, consultants told a panel of lawmakers Thursday afternoon.

“Based on the work that we performed, there weren’t any red flags,” Chris Ricchiuto, representing consulting firm Forvis Mazars, said.

The review was commissioned by the 2023 Legislature following complaints from local governments about the cost of the agency’s services.

The firm found that the State Auditor’s Office is following industry standards and laws, and is completing audits in a reasonable amount of time, said Charles Johnson, a director with the firm’s risk advisory services.

“The answer about the audit up front is that we identified four areas where things are working exactly as you expect the state auditor to do,” Johnson told the committee.

The report also found that the agency has implemented some policies to address concerns raised during the 2023 session.

For example, the Auditor’s Office now provides cost estimates to clients before they hire the office for services, Johnson said. The proposals include not-to-exceed clauses, so clients have to agree to any proposed changes.

The State Auditor’s Office also now includes more details on its invoices, so clients have more comprehensive information about what they’re being charged for.

The audit originally was intended to focus on fiscal years 2020 through 2023. However, the firm extended the scope of its analysis to reflect policy changes that the Auditor’s Office implemented after the 2023 fiscal year ended.

State Auditor Josh Gallion told lawmakers the period the audit covers was an unusual time for his agency. The coronavirus pandemic made timely work more difficult for his staff. Moreover, because of the influx of pandemic-related assistance to local governments from the federal government, the State Auditor’s Office’s workload increased significantly.

Gallion said that, other than confirming that the changes the agency has made were worthwhile, he didn’t glean anything significant from the audit.

“The changes had already been implemented,” he said.

Gallion has previously called the audit redundant and unnecessary. When asked Thursday if he thought the audit was a worthwhile use of taxpayer money, Gallion said, “Every audit has value, at the end of the day.”

The report has not been finalized, though the Legislative Audit and Fiscal Review Committee voted to accept it.

Audit of state auditor delayed; Gallion calls it ‘redundant, unnecessary’

“There was no shenanigans, there were no red flags,” Sen. Jerry Klein, R-Fessenden, said at the close of the hearing.

Forvis representatives told lawmakers they plan to finish the report sometime this month.

The contract for the audit is for $285,000.

Johnson said as far as he is aware Forvis has sent bills for a little over $150,000 so far. That doesn’t include the last two months of the company’s work, he said.

The consulting firm sent out surveys to local governments that use the agency’s services.

The top five suggestions for improvements were:

- Communication with clients

- Timeliness

- Helping clients complete forms

- Asking for same information more than once

- Providing more detailed invoices

The top five things respondents thought the agency does well were:

- Understanding of the audit process

- Professionalism

- Willingness to improve

- Attention to detail

- Helpfulness

Johnson said that some of the survey findings should be taken with a “grain of salt.”

“In our work as auditors, we don’t always make people happy doing what we’re supposed to do,” he said.

YOU MAKE OUR WORK POSSIBLE.

GET THE MORNING HEADLINES.

North Dakota

'False promise' or lifesaver? Insulin spending cap returns to North Dakota Legislature

BISMARCK — A bill introduced in the North Dakota House of Representatives could cap out-of-pocket insulin costs for some North Dakotans at $25 per month.

The bill also includes a monthly cap for insulin-related medical supplies of $25.

With insulin costing North Dakota residents billions of dollars each year,

House Bill 1114

would provide relief for people on fully insured plans provided by individual, small and large group employers. People on self-funded plans would not be affected.

“I call insulin liquid gold,” Nina Kritzberger, a 16-year-old Type 1 diabetic from Hillsboro, told lawmakers. “My future depends on this bill.”

HB 1114 builds on

legislation

proposed during the 2023 session that similarly sought to establish spending caps on insulin products.

Before any health insurance mandate is enacted,

state law

requires the proposed changes first be tested on state employee health plans.

As such, the legislation was altered to order the state Public Employees Retirement System, or PERS, to introduce an updated bill based on the implementation of a $25 monthly cap on a smaller scale.

The updated bill — House Bill 1114 — would bring the cap out of PERS oversight and into the North Dakota Insurance Department, which regulates the fully insured market but not the self-insured market.

Employers that provide self-insured health programs use profits to cover claims and fees, acting as their own insurers.

Fully insured plans refer to employers that pay a third-party insurance carrier a fixed premium to cover claims and fees.

“It (the mandate) doesn’t impact the entire insurance market within North Dakota,” PERS Executive Director Rebecca Fricke testified during a Government and Veterans Affairs Committee meeting on Thursday, Jan. 9.

Blue Cross Blue Shield Vice President Megan Hruby told the committee that two-thirds of the provider’s members would not be eligible for the monthly cap, calling the bill a “false promise.”

“We do not make health insurance more affordable by passing coverage mandates, as insurance companies don’t pay for mandates. Policy holders pay for mandates in the form of increased premiums,” Hruby said.

She touted the insurance provider having already placed similar caps on insulin products and said companies should be making those decisions, not the state government.

Sanford Health and the Greater North Dakota Chamber also had representatives testify against the bill.

Advocates for the spending cap said higher premiums are worth lowering the cost of insulin drugs and supplies.

“One of the first things that people ask me about is, ‘Why should I pay for your insulin?’ And my response is, ‘Why should I have to pay for your premiums?’” Danelle Johnson, of Horace, said in her testimony.

If adopted and as written, the spending caps brought by

House Bill 1114

would apply to the North Dakota commercial insurance market and cost the state around $834,000 over the 2025-27 biennium.

According to the 2024 North Dakota diabetes report,

medical fees associated with the condition cost North Dakotans over $306 billion in 2022.

The state has more than 57,200 adults diagnosed with diabetes, and a staggering 38% have prediabetes — a condition where blood sugar levels are high but not high enough to cause Type 2 diabetes.

Nearly half of those people are adults 65 years old or older.

North Dakotan tribal members were also found to be twice as likely to have diabetes compared to their white counterparts.

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoThese are the top 7 issues facing the struggling restaurant industry in 2025

-

Culture1 week ago

Culture1 week agoThe 25 worst losses in college football history, including Baylor’s 2024 entry at Colorado

-

Sports1 week ago

Sports1 week agoThe top out-of-contract players available as free transfers: Kimmich, De Bruyne, Van Dijk…

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoNew Orleans attacker had 'remote detonator' for explosives in French Quarter, Biden says

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoCarter's judicial picks reshaped the federal bench across the country

-

Politics6 days ago

Politics6 days agoWho Are the Recipients of the Presidential Medal of Freedom?

-

Health5 days ago

Health5 days agoOzempic ‘microdosing’ is the new weight-loss trend: Should you try it?

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoIvory Coast says French troops to leave country after decades