Lifestyle

Why Anthony Fauci approaches every trip to the White House as if it's his last

Dr. Anthony Fauci testifies before the House Oversight and Accountability Committee Select Subcommittee on June 3.

Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

For much of the past four years, Dr. Anthony Fauci has been the public face of the government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic — a status that garnered him gratitude from some, and condemnation from others.

For Fauci, speaking what he calls the “inconvenient truth” is part of the job. He spent 38 years heading up the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases at the National Institutes of Health, during which time he advised seven presidents on various diseases, including AIDS, Ebola, SARS and COVID-19.

Fauci still recalls the advice he received when he first went to the White House to meet President Reagan: A colleague told him to pretend each visit to the West Wing would be his last.

“And what he meant is, you should say to yourself that I might have to say something either to the president or to the president’s advisers … they may not like to hear,” Fauci explains. “And then that might lead to your not getting asked back again. But that’s OK, because you’ve got to stick with always telling the truth to the best of your capability.”

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Fauci clashed repeatedly with President Trump. “He really wanted, understandably, the outbreak to essentially go away,” Fauci says of Trump. “So he started to say things that were just not true.”

Fauci says Trump downplayed the seriousness of the virus, refused to wear a mask and claimed (falsely) that hydroxychloroquineoffered protection against COVID-19. “And [that] was the beginning of a situation that put me at odds, not only with the president, but more intensively with his staff,” Fauci says. “But … there was no turning back. I could not give false information or sanction false information for the American public.”

Fauci retired from the NIH in 2022. In his new memoir, On Call: A Doctor’s Journey in Public Service, he looks back on the COVID-19 pandemic and reflects on decades of managing public health crises.

Interview highlights

On appearing before the House Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Pandemic to answer questions about the pandemic response

If you look at the hearing itself it, unfortunately, is a very compelling reflection of the divisiveness in our country. I mean, the purpose of hearings, or at least the proposed purpose of the hearing, was to figure out how we can do better to help prepare us and respond to the inevitability of another pandemic, which almost certainly will occur. But if you listened in to that hearing … on the Republican side was a vitriolic ad hominem and a distortion of facts, quite frankly. As opposed to trying to really get down to how we can do better in the future. It was just attacks about things that were not founded in reality.

On his interactions with President Trump concerning COVID-19

He is a very complicated figure. We had a very interesting relationship. … I don’t know whether it was the fact that he recognized me as kind of a fellow New Yorker, but he always felt that he wanted to maintain a good relationship with me. And even when he would come in and start saying, “Why are you saying these things? You got to be more positive. You got to be more positive.” And he would get angry with me. But then at the end of it, he would always say, “We’re OK, aren’t we? I mean, we’re good. Things are OK,” because he didn’t want to leave the conversation thinking that we were at odds with each other, even though many in his staff at the time were overtly at odds with me, particularly the communication people. … So it was a complicated issue. There were times when you think he was very favorably disposed, and then he would get angry at some of the things that I was saying, even though they were absolutely the truth.

On reading reports of a mysterious illness afflicting gay men in 1981 (which later became known as AIDS)

I knew I was dealing with a brand new disease. … The thing that got me goosebumps is that this was totally brand new and it was deadly, because the young men we were seeing, they were so far advanced in their disease before they came to the attention of the medical care system, that the mortality looked like it was approaching 100%. So that, you know, spurred me on to … totally change the direction of my career, to devote myself to the study of what was, at the time, almost exclusively young gay men with this devastating, mysterious and deadly disease, which we ultimately, a year or so later, gave the name of AIDS to.

On the trauma of caring for patients with AIDS in the early years of the epidemic

All of a sudden I was taking care of people who were desperately ill, mostly young gay men who I had a great deal of empathy for. And what we were doing was metaphorically like putting Band-Aids on hemorrhages, because we didn’t know what the etiology was until three years later. We had no therapy until several, several years later. And although we were trained to be healers in medicine, we were healing no one and virtually all of our patients were dying. …

Many of my colleagues who were really in the trenches back then, before we had therapy, really have some degree of post-traumatic stress. I describe in the memoir some very, very devastating experiences that you have with patients that you become attached to who you try your very, very best to help them. … It was a very painful experience.

On working with President George W. Bush on the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), which aimed to combat the global HIV/AIDS crisis

The president, to his great credit, called me into the Oval Office and said we have a moral obligation to not allow people to die of a preventable and treatable disease merely because of the fact [of] where they were born, in a poor country, and that was at a time when we had now developed drugs that were absolutely saving the lives of persons with HIV, having them go on to essentially a normal lifespan here in the United States, in the developed world. So he sent me to Africa to try and figure out the feasibility and accountability and the possibility of getting a program that could prevent and treat and care for people with HIV. And I worked for months and months on it after coming back from Africa, because I was convinced it could be done, because I felt very strongly that this disparity of accessibility of drugs between the developed and developing world was just unconscionable. Luckily, the president of the United States, in the form of George W. Bush, felt that way. And we put together the PEPFAR program. … We spent $100 billion in 50 countries and it has saved 25 million lives, which I think is an amazing example of what presidential leadership can do.

On personally treating two patients with Ebola during the 2014 outbreak

The fundamental reason why I wanted to be directly involved in taking care of the two Ebola patients that came to the NIH is that if you look at what was going on in West Africa at the time — and this was during the West African outbreak of Ebola — is that health care providers were the ones at high risk of getting infected, and hundreds of them had already died in the field taking care of people in Africa — physicians, nurses and other health-care providers. So even though we had very good conditions here, in the intensive care setting, of wearing these spacesuits that would protect you, these highly specialized personal protective equipment, I felt that if I was going to ask my staff to put themselves at risk in taking care of people … I wanted to do it myself. I just felt I had to do that.

We took care of one patient who was mildly ill, who we did well with. But then the second patient was desperately ill. We did have contact with him, and we did get these virus-containing bodily fluids — everything from urine to feces to blood to respiratory secretions — we got it all over our personal protective equipment. And that was one of the reasons why you had to very meticulously take off your personal protective equipment so as not to get any of this virus on any part of your body. So the protocols for taking care of persons with Ebola in that intensive care setting were very, very strict protocols, which we adhered to very, very carefully. But it was a very tense experience, trying to save someone’s life who was desperately ill at the same time as making sure that you and your colleagues don’t get infected in the process.

Sam Briger and Joel Wolfram produced and edited this interview for broadcast. Bridget Bentz and Meghan Sullivan adapted it for the web.

Lifestyle

More than 60 ice cream products recalled over possible listeria contamination

Among the more than 60 products included in the recall are the Chipwich Vanilla Chocolate Chip ice cream sandwiches, Jeni’s Mint Chocolate Truffle pie ice cream sandwiches and Hershey’s Cookies & Cream Polar Bear ice cream sandwiches.

Chipwich / Jeni’s Ice Creams / Hershey’s Ice Cream

hide caption

toggle caption

Chipwich / Jeni’s Ice Creams / Hershey’s Ice Cream

As millions of Americans try to cool down during the record summer heat, a Maryland-based food manufacturer is recalling multiple brands of ice cream products sold nationwide that may have been contaminated with listeria, a potentially fatal bacteria.

The list of more than 60 affected products made by Totally Cool Inc. of Owings Mills, Md., includes brands such as Hershey’s, Friendly’s, Chipwich and Jeni’s. Pints of ice cream and sorbet, as well as ice cream cakes, sandwiches, cones and more are potentially tainted.

The Food and Drug Administration said there have been no reported illnesses so far.

Totally Cool halted production and distribution of the products after FDA sampling detected the presence of listeria, the agency said.

The company is investigating the presence of listeria and taking “preventative actions,” the FDA added, and no other Totally Cool products are included in the recall.

Totally Cool did not immediately respond to NPR’s request for comment.

Consumers who bought any of the recalled ice cream products are being urged to return the items for a full refund. Affected products can be identified using the date and plant codes printed on the product labels.

Chipwich said in a statement on its website that its parent company, Crave Better Foods LLC, “maintains and operates a small, separate production line” at the same Maryland facility as Totally Cool.

Chipwich called the recall “unfortunate” and said it was “taken out of an abundance of caution and care for the product and its loyal fans.”

Hershey’s Ice Cream said it has stopped sales of potentially impacted products following the recall from its manufacturing partner, Totally Cool. Hershey’s also asked consumers and dealers to throw away any possibly contaminated items they already had on hand.

The FDA says Listeria monocytogenes can lead to serious and occasionally fatal infections in young children, elderly people and anyone with a weakened immune system. Pregnant people infected with listeria can also suffer miscarriages or stillbirths.

Healthy people who eat food contaminated with the bacteria may experience a milder illness with symptoms including high fever, severe headache, stiffness, nausea, abdominal pain and diarrhea, the agency said.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, about 1,600 people are infected with listeriosis each year, and an estimated 260 of them die.

Lifestyle

Column: After years of running, I quit and took up Pilates. Here's how that turned out

About a year and a half ago, it occurred to me that if I didn’t start working out again, I’d be sliding into a sloppy, flabby late middle age.

I had always been a runner. For more than 30 years, my workout partner and I ran regularly along the oceanfront, from Venice to Santa Monica. Rain or shine, through pregnancies, child-rearing, PTAs, marital conflict and all the things that Zorba the Greek once described as “the full catastrophe,” we talked as we ran, becoming each other’s best therapist.

And then, sometime before the COVID-19 pandemic, my partner discovered a hot new form of exercise. Our running life as we knew it was basically over as I effectively became a pickleball widow.

In 2020, when the pandemic forced us inside, I pretty much stopped running.

Around the same time, my left knee began to ache and swell. I was certain it was a result of my rambunctious golden retriever smashing into my legs. But no, said the doctor, it was arthritis. (Me? So young?)

She referred me to physical therapy. The physical therapy office never returned my calls.

Desperate (and chubby), I decided to try Pilates. Why? Because all the women streaming in and out of the nearby Pilates studio had the kind of bodies I dreamed of having. And my knee was killing me.

My first, 45-minute Pilates class was a disaster. I was lost when the instructor called out the various positions — dancing bear, French twist, reverse kneeling crunch. I sat on the Megaformer machine, panting and feeling defeated.

“Why don’t you try a few private classes until you get the hang of it?” the studio owner suggested after I complained that she didn’t offer classes for rank beginners like me.

Over the course of the next year, I spent enough money on private lessons to buy a used car. In fact, I was spending so much that I was actually relieved when my cherished instructor told me she was moving to Amsterdam.

With trepidation, I began taking group classes again. This time, it was different. I knew what to do (mostly) and could keep up (mostly).

“Booty, booty, booty,” my class instructor, DeNae D’Auria, calls out as we, on all fours, donkey kick with a bungee cord over one foot to increase resistance.

“We don’t talk about pelvic floor stability enough,” says D’Auria, who is trained in Lagree, which expands on the core concepts of Pilates but is more intense.

“Love to see those shaky shakes,” she says, our muscles trembling as we do squats, lunges and planks enough to fill a lumber yard. “Remember to slow down and breathe. The secret is time under tension.”

I first encountered a Pilates machine almost 25 years ago at the home of the iconic hairdresser Vidal Sassoon, whom I was profiling for The Times. It seemed eccentric, but he looked fantastic for a man of 71.

Pilates classes are dominated by women, but the exercise was used to treat wounded and disabled soldiers soon after it was developed by Joseph Pilates, a German bodybuilder and gymnast who was interned by the British on the Isle of Man during World War I. He improvised the first versions of his famous machines by attaching bed springs to headboards and footboards to create resistance.

He called his system of exercise “Contrology,” focusing on breathing, the postural muscles of the back and the abdominal muscles we think of as the “core.”

After decades as a “little-known form of exercise with a devout but small following that included dancers, singers, circus performers and actors,” Pilates exploded in the mid- to late 1990s, according to the authors of the 2011 book “Pilates Anatomy.” Celebrities such as Madonna and Uma Thurman touted its benefits.

“It suddenly started appearing in Hollywood movies and television commercials, in cartoons and comedy shows, and on late-night television,” wrote Rael Isacowitz and Karen Clippinger. “It became synonymous with going to Starbucks and indulging in a low-fat triple-shot soy latte (no whipped cream, please!).”

The Pilates Foundation estimates that some 12 million people worldwide practice the exercise regimen. That’s a tiny fraction of the estimated 300 million or so who practice yoga.

“Scientific research does support an array of impressive health benefits for Pilates,” the New York Times reported in 2022. “Studies suggest it may help to improve muscle endurance and flexibility, reduce chronic pain and lessen anxiety and depression.”

Pilates’ place in popular culture was solidified in April, when “Saturday Night Live” took it on in a sketch that mocked the love-hate relationship it inspires in practitioners.

“Pilates,” says a deep-voiced narrator. “From the creator of ‘Saw X’ and the marketing director for Alo comes a chilling new look at girl horror.”

For people like me who came of age during the insane era of high-impact aerobics — thanks for the sciatica, Jane Fonda! — the low-impact nature of Pilates is appealing.

I usually do four 45-minute classes a week. I wouldn’t say I look like those lithe young women who surround me there — most are so young that I could be their mother — but a taut core has developed beneath my midriff bulge.

Oh, and that awful knee pain? It’s been gone for months.

Lifestyle

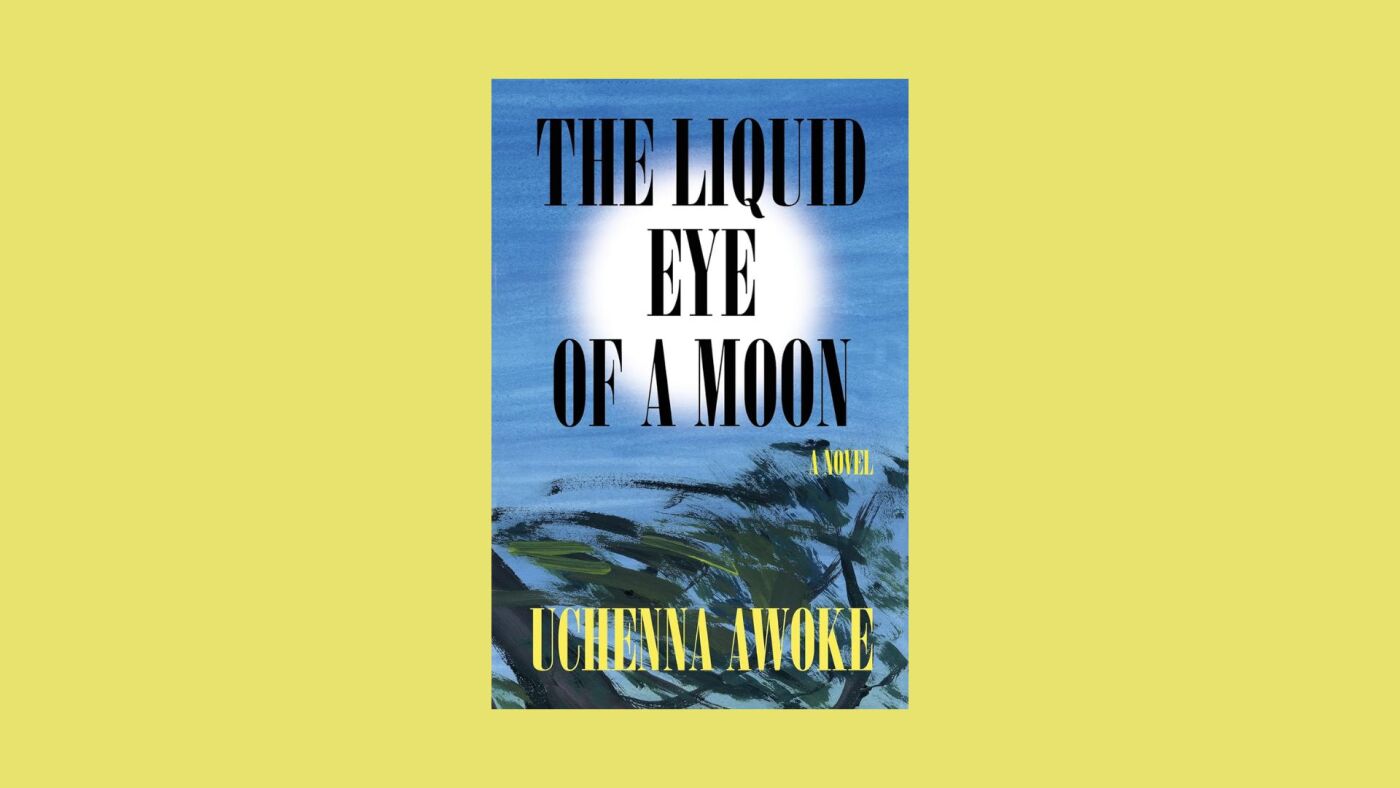

'The Liquid Eye of a Moon' is a Nigerian coming-of-age story

Uchenna Awoke’s debut novel The Liquid Eye of a Moon is, on the surface, 15-year-old Dimpka’s coming of age story in the rural Nigerian village of Oregwu. But Dimpka’s story is bigger than this — as it takes place within the specific context of what Awoke calls “human tabooing.”

The novel delves into life in an Igbo family that is considered “unclean” because they fall on the lowest rung of the traditional Igbo caste system. There are varying explanations or “justifications” for these harsh social divisions, including a specific type of ancestor worship. One practice is to dedicate a child to an ancestor, thereby “enslaving” the child to that forebear.

Dimpka’s devotion to his deceased aunt may reflect this spirituality. He is a dreamer, and his most important desire is to build a proper tomb for his aunt Okike, who died by drowning. Although his memory is hazy, Dimpka knows this aunt was extremely close to him. It is not until the end of the book that we learn the details of her death, disclosing why Dimpka may be so driven to give her a proper burial.

This novel also takes place against a history of horrific ethnic cleansing. To vastly oversimplify: The Nigerian government undertook a 1966 pogrom that killed thousands of Igbo people. The Igbos rose up to declare the independent republic of Biafra. The Biafran war for liberation, often called the Nigerian civil war, evoked headlines around the world. It ended in 1970 with the crushing defeat of the nascent Biafran republic. Accounts of the Biafran war have been memorialized in Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s searing novel, Half of a Yellow Sun, Chinua Achebe’s iconic book, There Was a Country, Louis Chude-Sokei’s terrific memoir, Floating in a Most Peculiar Way, and elsewhere.

Awoke presumes the reader’s knowledge of this complex background. He declines to translate Igbo terms, sharpening his message that Igbo cultural and political history form the novel’s warp and weft.

Dimpka carries the weight of being the eldest son in his family. He narrates his story in the first person. His maturation is marked by increasing awareness of caste differences, and the grave disappointments and dangers they engender. His closest friend, Eke, cannot bring Dimpka to his home due to social divisions. But the boys’ friendship transcends these taboos, and they explore their village together and share adventures until fate intervenes.

Dimpka’s father fought for Biafran independence but remains in the lowest class, and, as such, is unfairly passed over to be village elder. Dimpka’s parents may have anticipated this injustice, but it wounds the family, especially Dimpka.

Dimpka experiences sharp divisions within his own family as well. His younger brother Machebe taunts him with his self-discipline and consequent generosity and success.

Their father follows a traditional Igbo religious practice that invokes punishing gods, including Ezenwanyi, a commanding queen. Awoke intersperses these ritual stories throughout the book, casting a shadow across Dimpka’s activities.

By contrast, Dimpka’s mother is Pentecostal, and at pains to ensure her children’s Christian salvation.

How can Dimpka contain these divisions and move forward in his life? Throughout his teens and early 20s he tries multiple schemes to lift himself up in society and earn enough to build his aunt’s tomb and bring his family out of poverty. He proceeds as a hopeful innocent, while the reader fears for him. He follows paths that result in his being defrauded, shamed, and beaten down physically and emotionally. His struggles lead to a growing sense of frustration and pessimism. We come to understand that his choices are painfully constricted by the caste system into which he was born.

The moon in the title figures prominently in many scenes. When Dimpka finally succeeds in building his aunt’s tomb, he lies on it beside her, and looks “into the big liquid eye of a moon.” “Liquid” in the title brings to mind the fluidity of life and the lack of control humans have over their fate.

My reading of this novel would have been greatly enhanced by a clearer understanding of Igbo culture and history. Nevertheless, I enjoyed being immersed in Dimpka’s life, the tastes and smells of his mother’s cooking, the description of his fellow villagers, and his travels to Lagos and elsewhere to improve his lot. We feel the dust in the streets and engage in the activity at the local market. These setting and atmospherics help illustrate the suffering imposed on members of Dimpka’s caste.

Awoke’s writing is impressive; his metaphors are refreshing and vivid. Sentences like “Eke lights his crackling bush-fire laughter,” make Dimpka’s friend Eke come alive. Dimpka gives this specific description of his brother Machebe: “Imagine a tiger incarnate with a hard orange-brown stare.”

The book ends on an affirmative, though abrupt, note, with insufficient lead up to its conclusion. If such an ending suggests a novelist new to his craft, the book itself suggests a writer of great promise. Dimpka’s meandering story carries a vital humanitarian message. I look forward to reading more of Uchenna Awoke’s work.

Martha Anne Toll is a D.C.-based writer and reviewer. Her debut novel, Three Muses, won the Petrichor Prize for Finely Crafted Fiction and was shortlisted for the Gotham Book Prize. Her second novel, Duet for One, is due out May 2025.

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoProtesters in Brussels march against right-wing ideology

-

Movie Reviews1 week ago

Movie Reviews1 week agoShort Film Review: Willow and Wu (2024) by Kathy Meng

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoA fast-moving wildfire spreads north of Los Angeles, forcing evacuations

-

Movie Reviews1 week ago

Movie Reviews1 week agoFancy Dance (2024) – Movie Review

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoTrump resurrects Biden's 'devastating' 1994 crime bill as he courts Black Detroit voters: ‘Super predators'

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoVideo: An American’s Desperate Effort to Save Her Family in Gaza

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoRead the Ruling by the Virginia Court of Appeals

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoRussia sets date for closed-door trial of US journalist