Lifestyle

What Dennis Rodman, Kate Moss and a 5,000-year-old Alpine iceman have in common

Book Review

Painted People: 5,000 Years of Tattooed History from Sailors and Socialites to Mummies and Kings

By Matt Lodder

William Collins: 352 pages, $21.99

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

One of the most stubborn misconceptions about tattooing is that it was born in Polynesia and imported to the West by Captain Cook in 1768, then trickled down to the masses over the next century, settling into military and criminal subcultures until its late-20th century resurrection in the middle class. It’s not only false but also eclipses a much broader and more complex global heritage.

Matt Lodder’s “Painted People: 5,000 Years of Tattooed History from Sailors and Socialites to Mummies and Kings” brings that truth to life in 21 riveting stories. Lodder, a scholar of tattoo history, doesn’t argue for the artistry or legitimacy of tattoos but rather shows — in lively and accessible language — how they serve as points of entry into so many aspects of culture: history and anthropology, sports and fashion, war and medicine. Lodder examines their material and spiritual origins as well as their cultural impact.

“I want to show you that tattooing connects us across historical time and geographical space, revealing details about human experience in the process,” he writes.

Though it’s organized by period, from the ancient world to the new millennium, “Painted People” is not a chronology. Tattoo history is not linear, and its timelines are always shifting.

The book opens with the story of Ötzi, one of the oldest known tattooed humans, whose more-than-5,000-year-old body was found preserved in the Italian alps in 1991. It also details the recent discovery of 3,000- to 5,000-year-old tattoo tools in Tennessee, which bumped the origins of North American tattooing back a full millennium.

Both cases present tantalizing mysteries: Because most of Ötzi’s dozens of abstract tattoos appear in places where only a right-handed person could reach, it’s possible that he tattooed himself. And when chiseled turkey bones were unearthed on Tennessee land once inhabited by the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Shawnee and Yuchi peoples, archaeologists weren’t sure if they were for tattooing, medicinal uses or leatherworking. In what Lodder calls “an act of gonzo archaeology,” the scientists carved their own needles from turkey bones, dipped them in ink, tattooed themselves and concluded, based on microscopic examination of their “wear patterns,” that the ancient needles only could have been used to tattoo.

(Courtesy of HarperCollins)

“Painted People” is such a robust miscellany that it’s possible to dip in anywhere and find something astonishing: the artist Lucian Freud tattooing swallows on supermodel Kate Moss; a Tang-era Chinese text describing a peacock gallbladder used as tattoo ink; North Korean prisoners of war forcibly marked with anti-communist slogans; Christian and Islamic pilgrimage tattoos thriving in 16th century Jerusalem; and, in a spasm of Cold War anxiety, Indiana schoolchildren tattooed with their blood types under their left armpit, just as Nazi soldiers had been during World War II. The location, Lodder explains, was “least likely to be seriously burned or slashed by flying debris.”

Not every story involves blood and ink: In 1929, following a tattoo craze among young people in the U.S. and Britain, the designer Elsa Schiaparelli created custom swimsuits featuring patterns from an array of classic tattoos copied, she said, “from the manly chests of French mariners.” Knitted into “sunburn”-colored fabric, the garments made beachgoers appear nearly naked but for the mermaids and pierced hearts hugging their torsos. “The hypermasculine associations of tattooing” suited the moment, Lodder writes, “as androgyny and boyishness had become de rigueur.”

Like many folk art and Indigenous practices, says Lodder, tattooing tends to be fundamentally “conservative, preserving imagery and iconography over centuries, if not millennia … often communicating quickly and bluntly rather base and universal emotions about fear, hope, and familial ties.” Even custom tattooing in the West, he notes, “almost inevitably” signifies group rather than individual identity.

The 1990s NBA star Dennis Rodman, by contrast, used his ink — along with his piercings, dresses and technicolor hair — to mark himself as “a true individual in a deeply conservative culture.” Like soldiers and convicts whose individual identities are disguised by uniforms, athletes have few options for creative self-expression. But basketball players’ exposed skin provided an alluring public canvas that Rodman filled with tattoos, inspiring generations of athletes to do the same. His passion for the art form also helped integrate the white-dominated tattoo world, where for too long Black customers had been told their skin was too dark to carry legible designs.

When Rodman sued a company selling T-shirts mimicking his tattooed torso, he prefigured a 21st century tattoo problem: fair use. The appearance of custom tattoo designs in films, fashion and video games has been legally contested. But, Lodder asks, if a finished tattoo itself infringes on a copyright, how can a “cease and desist” order be enforced? Likewise, what are the legal implications of a hacked numeric decryption code tattooed on a man’s body and then photographed and shared online? Though tattooing has changed little technically since ancient times — apart from the 19th century invention of the tattoo machine — modern technology is investing it with thorny new implications.

The tattooist Ed Hardy once said that tattoos are like “little vents” into the wearer’s psyche. Lodder presents them as portals to whole peoples. Some of their practices were canceled by colonialism; others, preserved in ice as Ötzi was, are dissolving with the melting permafrost, taking the visual keys to ancient cosmologies with them. Deeply researched and elegantly written, “Painted People” is a moving, entertaining tribute to the people — and peoples — behind this underexamined medium.

Margot Mifflin is a professor at the City University of New York and the author of “The Blue Tattoo: The Life of Olive Oatman.”

Lifestyle

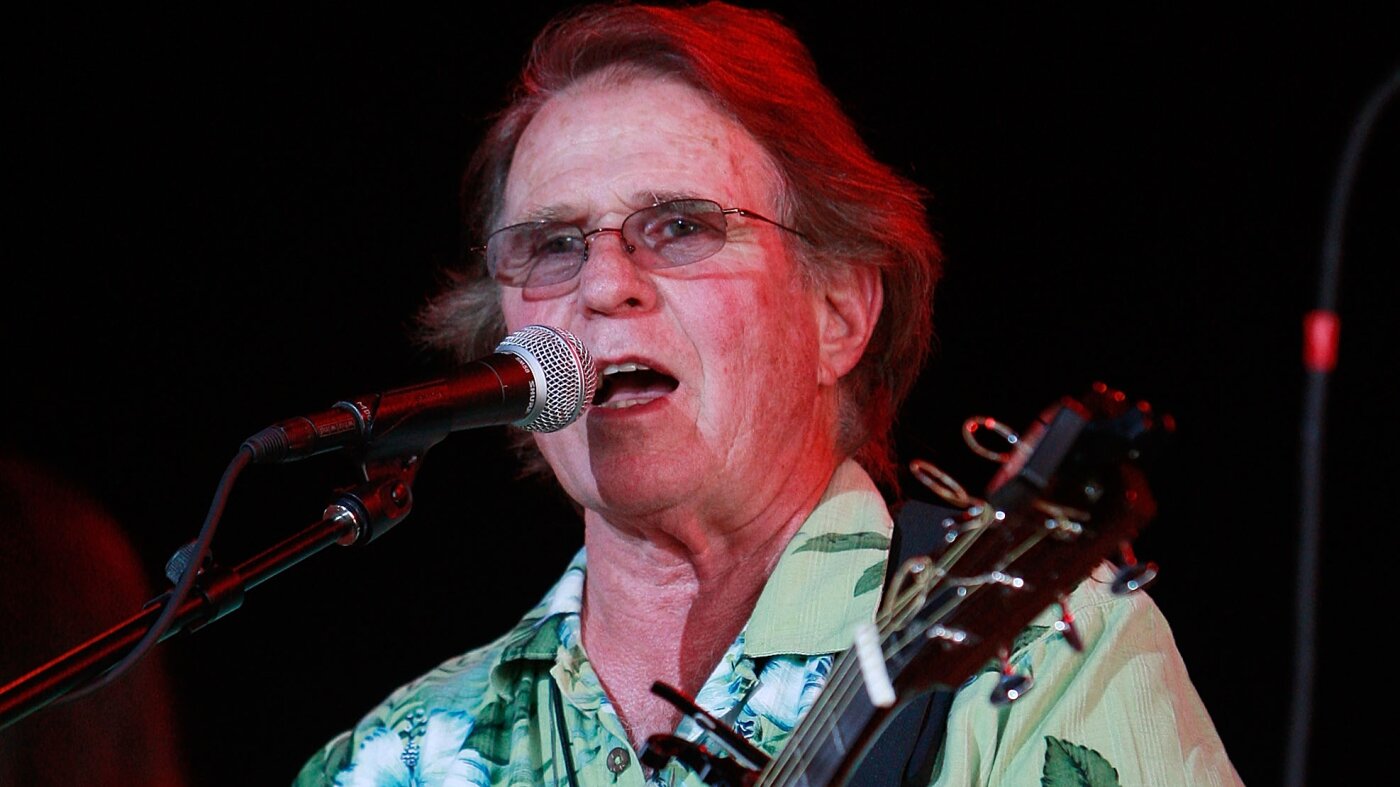

Country Joe McDonald, anti-war singer who electrified Woodstock, dies at 84

Singer Joe McDonald sings during the concert marking the 40th anniversary of the Woodstock music festival on Aug. 15, 2009 in Bethel, New York. McDonald has died at age 84.

Mario Tama/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Mario Tama/Getty Images

Country Joe McDonald, the singer-songwriter whose Vietnam War protest song became a signature anthem of the 1960s counterculture, has died at 84.

McDonald died on Saturday in Berkeley, Calif., according to a statement released by a publicist. His health had recently declined due to Parkinson’s disease.

Born in 1942, in Washington, D.C., he grew up in El Monte, Calif., outside Los Angeles, according to a biography on his website. As a young man he served in the U.S. Navy before turning to writing and music during the early 1960s, eventually becoming involved in the political and cultural ferment of the Bay Area.

In 1965 he helped form the band Country Joe and the Fish in Berkeley. The group became part of the emerging San Francisco psychedelic music scene, blending folk traditions with electric rock and pointed political commentary.

The band’s best-known song, “I-Feel-Like-I’m-Fixin’-to-Die Rag,” captured the growing anti-war sentiment of the Vietnam era. With its ragtime-influenced rhythm and sharply satirical lyrics about war and political leadership, the song quickly became associated with protests against the conflict.

McDonald delivered the song to some half a million people at the 1969 Woodstock festival in upstate New York. Performing solo, he led the crowd in a form of call-and-response before launching into the anti-war anthem, turning the performance into one of the defining scenes of the festival.

Country Joe and the Fish released several recordings during the late 1960s and toured widely, becoming closely identified with that era’s West Coast rock and protest movements.

McDonald later continued performing and recording as a solo artist, recording numerous albums across a career that spanned more than half a century. His work drew variously from folk, rock and blues traditions and often reflected his long-standing interest in political and social issues.

Although he became widely known for his opposition to the Vietnam War, McDonald frequently emphasized respect for those who served in the U.S. military. After his own service in the Navy, he remained engaged with veterans’ issues and occasionally performed at events connected to veterans and their experiences, according to his website biography.

Lifestyle

Country Singer Maren Morris Tells Donald Trump Supporters ‘You Voted For This’

Maren Morris to Trump Voters

You Got Bamboozled!!!

Published

Country music star Maren Morris is speaking her mind about what she sees as the failures of the Trump administration, and she doesn’t care if she loses fans over it.

According to Maren Morris, if you supported Donald Trump in his presidential elections, you voted for a “dementia ridden, diaper clad, cornball” and “you got bamboozled.”

Not only that … she doesn’t feel bad for the MAGA faithful who may feel disillusioned by their leader.

In a TikTok posted Friday, she said, “The is literally the result of ploying and voting for losers.”

Morris has expressed her dismay at music becoming so political since she’s jumped onto the scene — something she’s benefitted from due to songs like “My Church” — but she’s clearly not shy about her views.

“If you don’t agree with me … you can’t enjoy my music because of my viewpoints? You’re absolutely allowed to do that,” she said. “But I am only here for an iteration of revolutions around the sun, a couple, and so I do feel like I have sacrificed a lot of my mental health, my financial standing, my family, just because I am so deeply concerned and uncomfortable with the weird status quo of country music.”

Lifestyle

Photos: These bold women stand up for justice, rights … and freedom

Jean, 72, a Chinese opera performer, poses for a portrait before performing in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

Annice Lyn/Everyday Asia

hide caption

toggle caption

Annice Lyn/Everyday Asia

March 8 is International Women’s Day — a date picked in honor of a remarkable Russian protest.

During World War I, women in Russia went on strike. They demanded “bread and peace.” Among the results of their four-day protest: the Czar abdicated and women gained the right to vote.

This bold strike began on Feb. 23, 1917, according to the Julian calendar then used in Russia. That date translated to March 8 in the Gregorian calendar that much of the world uses. So that’s the day chosen for this celebratory event.

True to the spirit of those Russian women, the world pauses on this day to celebrate the achievements of women. This year to mark International Women’s Day, the United Nations is calling for “Rights. Justice. Action. For all women and girls.”

Sometimes, the true achievements are the ones that we barely see. The photographers at The Everyday Projects, a global photography and storytelling network, have shared portraits of women who in ways large and small are determined, like those Russian women over 100 years ago, to improve the lives of women and to build a better world.

Singing with strength

Kuala Lumpur-based photographer Annice Lyn likes to highlight the strength, resilience and the stories of women who are often overlooked.

That’s the inspiration for her portrait of Jean, 72, as she prepares for a performance of Chinese opera at Kwai Chai Hong, a restored heritage alley in Kuala Lumpur’s Chinatown in August 2024.

Such performances, typically staged during festivals and temple celebrations, combine singing, acting, martial arts, elaborate costumes and symbolic makeup to tell classical stories from Chinese folklore, history, and literature.

“Performers like Jean often dedicate decades of their lives to mastering this art form, preserving techniques and stories that are centuries old,” says Lyn. They told her that they may encounter negative reactions — questions like “are you wasting your time” or simply indifference.

“Sustaining a centuries-old practice in a modern urban setting requires both resilience and passion,” says Lyn, who made this picture minutes before the performance. “I wanted to give Jean the dignity she deserves through this portrait, a strong, intimate image that acknowledges her beauty, her discipline and the life she has dedicated to Chinese opera. I hoped to make her feel seen and heard, capturing not just a performance but a living cultural legacy.”

Dreaming of a toilet

Nkgono Selina Mosima, a resident of Thaba Nchu, Free State, South Africa, has hoped for years that she could afford to dig a pit toilet in her yard.

Tshepiso Mabula/The Everyday Projects

hide caption

toggle caption

Tshepiso Mabula/The Everyday Projects

The subject is Nkgono Selina Mosima, a resident of Thaba Nchu, Free State, South Africa, a region where poverty is rampant, Mosima is one of many residents who lack proper sanitation, says Tshepiso Mabula, a photographer and writer based in Johannesburg. Her wish was to hire someone to dig a pit toilet in her yard – in which human waste is collected in a pit and allowed to break down naturally over time – but she couldn’t afford the cost. The alternative is open defecation – finding a secluded place despite the personal risks and the potential health consequences of untreated human excrement.

“I was drawn to Nkgono by her unrelenting faith and positive outlook; despite her difficult circumstances, she constantly reiterated her hope that things would improve,” says Mabula. “This inspired the framing of the portrait: the bright colors, her headscarf and the belt around her waist all serve to highlight her strength, optimism and faith.”

The picture was taken in 2020. Today, Mabula says, many women still lack safe and effective sanitation options. Nkgono was a powerful voice for action and change as she eventually could afford to dig a pit toilet on her property.

Russian footballers

These women from Voronezh, Russia, participated in the country’s short-lived but intense American-style football league. They’re hanging out in the locker room.

Kristina Brazhnikova/Everyday Russia

hide caption

toggle caption

Kristina Brazhnikova/Everyday Russia

It seems improbable — starting an American football league for women in Russia. Not soccer but football. That’s what Portugal-based photographer Kristina Brazhnikova is documenting in her project “Mighty Girls,” which she shot between 2018 and 2021.

Any Russian woman could join, regardless of age, body type or level of training, she says. Coaches from the U.S. women’s national football team participated.

In the photo, the girls from the Voronezh team “Mighty Ducks” (Gabi, Katya, and Olesia) are in the locker room of a training camp preparing for practice. Team members came up with the name, she says.

“Everything was built on enthusiasm, so the players had to study the rules and playbooks on their own. Some women were invited by friends, others were drawn to the unusual nature of the sport, and some simply wanted to improve their physical fitness,” says Brazhnikova, who is Russian herself.

After the first practice, many women decided the game wasn’t for them, she says. It requires not only strength and endurance but the ability to memorize complex plays. Players had to buy their own protective gear, pay for field rentals and cover their travel expenses to competitions in other cities.

“Those who stayed, however, found a new family,” says Brazhnikova — and a new form of expressing emotions, including aggression. The women told her that playing American football made them braver and more decisive. They allowed themselves to step outside their comfort zones and push beyond the limits of their usual lives. They changed jobs and left relationships that had run their course. And the sound of pads colliding on the field became their favorite,” she says.

The league ceased to operate in 2022.

Hunting for missing loved ones

Hilaria Arzaba Medran of Mexico stands with tools she’ll use as she searches a clandestine burial site for the grave of her son, Oscar Contreras Arzaba, who disappeared in 2011 at age 19.

James Rodríguez/Everyday Latin America

hide caption

toggle caption

James Rodríguez/Everyday Latin America

Hilaria Arzaba Medran, 57, is no stranger to loss. Her son Oscar Contreras Arzaba disappeared on May 22, 2011, at the age of 19. A resident of the Mexican state of Veracruz, she’s a member of Solecito, an organization whose 250 members go out and look for their missing relatives on a regular basis. Holding tools in this photograph taken in Feb. 20, 2018, she searches for her missing son and other victims in a location known to have served as a clandestine grave.

“This collective is primarily led by women, and I was awe-struck by their determination to find their loved ones despite horrific violence and real-life threat to their own well-being,” says photographer James Rodríguez.

On this occasion in 2018, Rodriguez and others in the group had received an anonymous tip of a possible clandestine cemetery on the outskirts of Cordoba. She went searching with several other collective members, digging tools in hand. “We went into an isolated rural field that felt macabre in itself and [we] had no sort of security personnel with us. I was truly astounded by their conviction and courage,” he says.

A demand for housing

Janaina Xavier, a community leader, holds her son in a building in São Paulo, Brazil, that was occupied by people without housing in 2024.

Luca Meola/Everyday Brasil

hide caption

toggle caption

Luca Meola/Everyday Brasil

Janaina Xavier, a community leader, holds her son while looking out the window of the building where she lives with six of her 10 children near the Cracolândia district in São Paulo, Brazil, on April 23, 2024.

She currently serves as a council member for the Coordination of Policies for the Homeless Population and advocates for the rights of people living in and around Cracolândia.

“I’ve known Janaina Xavier for many years, since I began my long-term work documenting Cracolândia in São Paulo. She has long been involved in struggles for housing rights for people living in this highly stigmatized region of the city,” says photographer Luca Meola.

This photograph was taken inside a building being illegally occupied by Xavier and dozens of other families – a way for them to secure housing in the city center.

“For many low-income families, occupying empty buildings is one of the only ways to remain in the central area and access essential services and work opportunities,” Meola says.

In 2025, the city evicted Xavier, her family and the other residents.

The mother leaders of Madagascar take charge

In the Grand South of Madagascar, women known as “reny mahomby,” or mother leaders, perform a welcoming dance before starting a session to teach women in the community how to improve their lives.

Aina Zo Raberanto/The Everyday Projects

hide caption

toggle caption

Aina Zo Raberanto/The Everyday Projects

In this photo from the Grand South of Madagascar, in Amboasary Sud, women known as “Reny Mahomby,” or “mother leaders” perform a welcoming dance.

The “mother leaders” inspire other mothers in the community to make changes in their lives – to improve hygiene, to educate their children, to start small businesses, says photojournalist Aina Zo Raberanto, who lives in this African island nation but had never before visited the Grand South.

The dance took place at the start of a training session, says Raberanto. In this photo from November 2021, she says. “These mother leaders welcome us with a traditional dance from the region. I was deeply moved by their commitment to their community.”

The mothers of Madagascar “are the pillars of the household while sometimes facing difficult realities such as violence or early marriage,” she says. “I took this photograph to show both their strength, their dignity, their joy for life and the warmth of their welcome despite the hardships. Behind their smiles and movements lies a great determination to continue supporting their families and to build a better future for their children.”

Marching for their rights

Members of Puta Davida, a feminist collective advocating for the labor and human rights of sex workers, take part in a march during Carnival in downtown Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, on Feb. 14, 2026.

Luca Meola

/Everyday Brasil

hide caption

toggle caption

Luca Meola

/Everyday Brasil

This photograph was taken during Carnival in Rio de Janeiro this February.

“I have been accompanying the collective Puta Davida for about three years. [It] works to create public debate around sex work, advocating for the recognition of sex work as legitimate labor and for the protection of sex workers’ human and labor rights,” says photographer Luca Meola.

The Puta Davida is a feminist collective from Rio de Janeiro created in the early 1990s by the sex worker and activist Gabriela Leite, a historic figure in Brazil’s movement for sex workers’ rights.

“I have been accompanying the collective for about three years. [It] works to create public debate around sex work, advocating for the recognition of sex work as legitimate labor and for the protection of sex workers’ human and labor rights,” says photographer Luca Meola.

In 2026, one of the community organizations that prepares music, dance, and large performances for Carnival parades chose to dedicate its parade to sex workers

Meola, who photographed the members of this group as they marched, says: “For me, what is powerful about this moment is how these women reclaim visibility in public space. Through political organization, performance and collective presence, they challenge stigma and assert their rights — which I believe strongly resonates with this year’s theme [for International Women’s Day] of justice and action,” says Meola.

Kamala Thiagarajan is a freelance journalist based in Madurai, Southern India. She reports on global health, science and development and has been published in The New York Times, The British Medical Journal, the BBC, The Guardian and other outlets. You can find her on X @kamal_t

-

Wisconsin1 week ago

Wisconsin1 week agoSetting sail on iceboats across a frozen lake in Wisconsin

-

Massachusetts6 days ago

Massachusetts6 days agoMassachusetts man awaits word from family in Iran after attacks

-

Maryland1 week ago

Maryland1 week agoAM showers Sunday in Maryland

-

Florida1 week ago

Florida1 week agoFlorida man rescued after being stuck in shoulder-deep mud for days

-

Pennsylvania4 days ago

Pennsylvania4 days agoPa. man found guilty of raping teen girl who he took to Mexico

-

Oregon1 week ago

Oregon1 week ago2026 OSAA Oregon Wrestling State Championship Results And Brackets – FloWrestling

-

News1 week ago

News1 week ago2 Survivors Describe the Terror and Tragedy of the Tahoe Avalanche

-

Sports5 days ago

Sports5 days agoKeith Olbermann under fire for calling Lou Holtz a ‘scumbag’ after legendary coach’s death