Lifestyle

This could be the way we watch movies in the future

Visitors watch Jesus VR: The Story of Christ during the 73rd Venice Film Festival in 2016.

Andreas Rentz/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Andreas Rentz/Getty Images

Marvel Studios’ What If…? — An Immersive Story is tricky to describe. Part interactive game, part narrative-driven movie and part 3D comic book, it puts you — the viewer? the player? — at the center of a narrative that reimagines the fates of superheroes and villains from the Marvel Cinematic Universe.

To experience What If…? you must wear an Apple Vision Pro headset, which is considered “mixed reality.” That means that it incorporates both virtual reality, or VR — transporting you to a different world — as well as augmented reality, or AR — where other video is layered on top of the actual room that you are in. The story toggles between scenes in AR in which characters appear to materialize in the user’s real room, and a series of dizzying VR landscapes in the Multiverse.

Some parts involve passive viewing, like a sequence in which the supervillain Thanos is on trial for theft. But there’s also a lot of interactivity: one character explains how to use hand gestures, like making a fist, to defend yourself against enemies and cast magic spells.

A screenshot from What If…? — An Immersive Story.

Marvel Studios/ILM Immersive

hide caption

toggle caption

Marvel Studios/ILM Immersive

This is a much different experience than traditional TV or movie watching, and industry insiders think it will change the face of entertainment.

“It’s kind of creating a new canvas,” said ILM Immersive’s Shereif Fattouh, the executive producer of the immersive version of What If…?.

Although interactivity is at the heart of the experience, viewers can opt out.

“There’s a lot of audience that are traditional gamers that really want to shoot things,” Fattouh said. “And there’s folks that don’t play games and want to just see a great story.”

Catering to a wide variety of tastes

Gamers have been using VR systems for decades. But in the last 10 years or so, new headsets — with more powerful graphics and motion tracking technologies — have started to broaden audiences.

The current entertainment offerings cater to a wide variety of tastes. For example, Meta headset users can sit with friends at an NBA basketball game with its Xtadium app, explore a haunted Irish castle in The Faceless Lady, a VR live action horror series, or take in pop star Sabrina Carpenter’s recent immersive VR concert.

Trailer for ‘The Faceless Lady,’ a VR horror TV series

YouTube

“Sitting courtside at your favorite basketball game or seeing your favorite superhero is a completely different experience [in virtual reality],” said Jason Thompson, the creator and host of The Construct, a consumer VR-focused YouTube channel. “It can’t really be compared to watching things on a flat screen.”

Thompson said he uses apps like Bigscreen to watch traditional TV shows and films in his headset. If he chooses, it can be a social experience; users can chat with others at a watch party or mute them if there’s too much conversation. They can also change their surroundings, so a living room couch transforms into what seems like a plush movie theater, complete with virtual popcorn. Thompson said he sometimes watches in Bigscreen’s bedroom setting, lying flat on a bed.

“The screen is actually on the ceiling,” said Thompson. “And you have to lay back to see the screen.”

Lying down to watch content in VR isn’t just whimsy. It serves a practical purpose. Most of today’s headsets are heavy and awkward to wear. Thompson said reclining to watch takes the load off the head and neck.

“In order for VR to excel it has to become comfortable,” he said.

An industry finding its feet

Tech players are working on it.

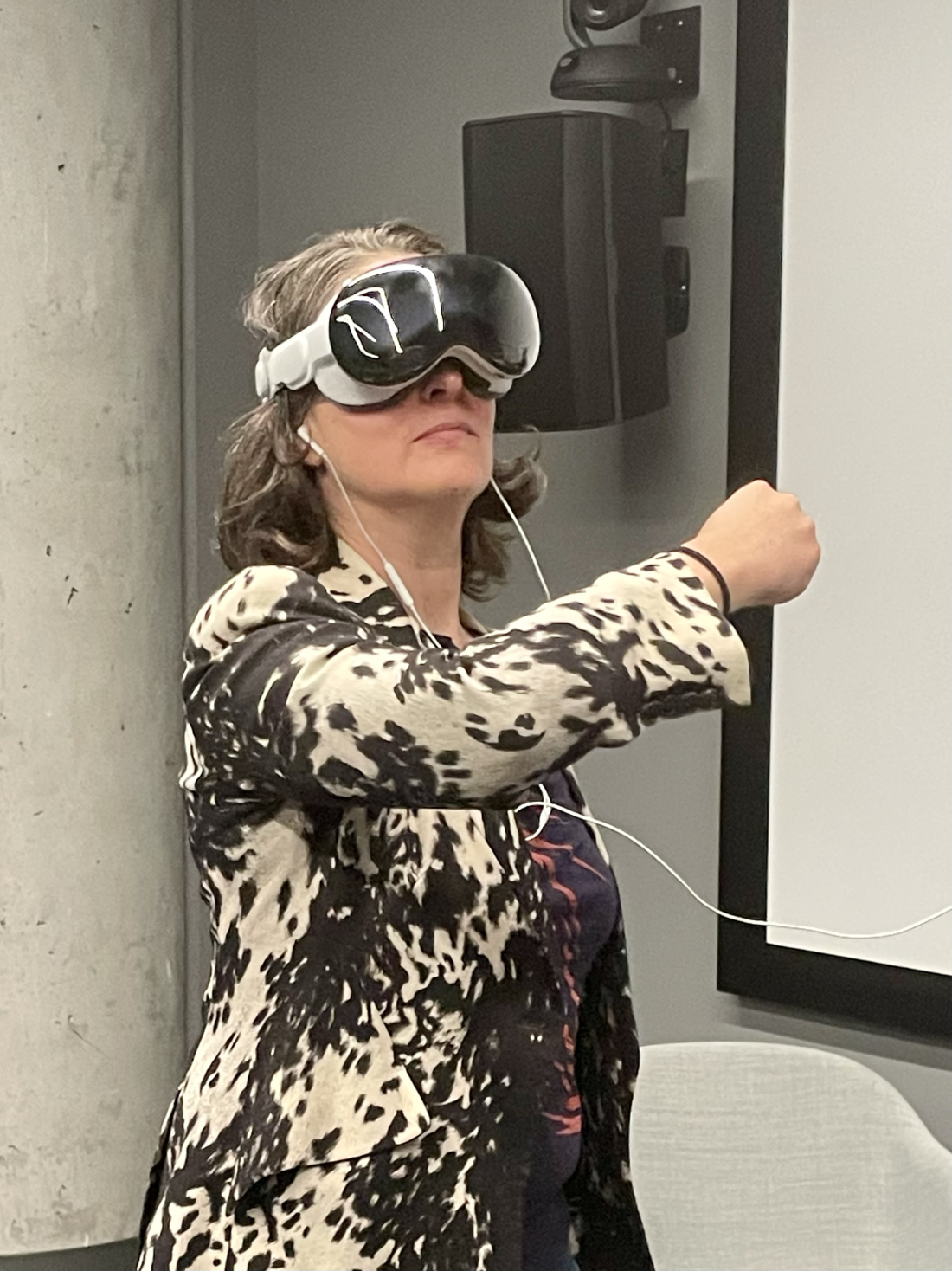

NPR correspondent Chloe Veltman tries What If…? An Immersive Story at ILM Immersive’s headquarters in San Francisco.

Chloe Veltman/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Chloe Veltman/NPR

“As every year passes and we improve the technology, make it easier to set up, more seamless to what you do on other devices, we see more and more people actually adopt,” said Sarah Malkin, director of immersive entertainment at Meta, the current market leader in consumer VR. “We knew we would be investing in what is essentially the future of computing and that it would take time.”

Malkin said Apple’s arrival in the market — it launched the Apple Vision Pro in February — is a good sign that headsets are becoming more mainstream, even as they cost anywhere from $300 to more than $3,000. However, Apple and Meta are not disclosing specific sales figures, so it’s hard to know for sure how the market is developing.

“The key for this market is consumer adoption,” said Ben Arnold, a consumer technology analyst with the market research firm Circana. “Because that is something that makes development of the applications more attractive.”

Adoption depends on both tech and content

Filmmakers say that the technology also needs to be friendly to creatives, so they can tell better stories in VR.

“The basic interaction methods have yet to be figured out,” said VR film writer and director Eugene Chung of Penrose Studios, the company behind several VR movies, including Arden’s Wake, a post-apocalyptic ocean adventure which won the first Lion Award for Best VR at the Venice Film Festival in 2017. “It should feel as natural as using your iPhone. And we’re so far away from that.”

Penrose – Arden’s Wake – Trailer

YouTube

Chung said it’s easy for people to get frustrated with many of the current TV and film VR offerings because users don’t know where to direct their attention in a given scene, or they want to fully interact with a character but often can’t.

“You see stuff happening, but things aren’t reacting to you the way that you think they should,” Chung said. “For example, you can’t just go up to a character and talk to them about Shakespeare or ask them about what they ate for lunch.”

Yet he’s excited about continuing to explore the creative potential of this new medium, especially since many young people today are growing up as VR natives.

“I have no doubt that this will be the future of all of entertainment and really all of computing,” he said.

Jennifer Vanasco edited the audio and digital versions of this story. Isabella Gomez Sarmientomixed the audio version.

With thanks to Will Mitchell and James Mastromarino

Lifestyle

Video: Prada Peels Back the Layers at Milan Fashion Week

new video loaded: Prada Peels Back the Layers at Milan Fashion Week

By Chevaz Clarke and Daniel Fetherston

February 27, 2026

Lifestyle

Bill Cosby Rape Accuser Donna Motsinger Says He Won’t Testify At Trial

Bill Cosby

Rape Accuser Says Cosby Won’t Take Stand At Trial

Published

Bill Cosby‘s rape accuser Donna Motsinger says the TV star can’t be bothered to show up to court for a trial in a lawsuit she filed against him.

According to new legal docs, obtained by TMZ. Motsinger says Bill will not testify in court … she claims it’s “because he does not care to appear.”

Motsinger says Bill won’t show his face at the trial either … and the only time the jury will hear from him will be a previously taped deposition.

As we previously reported, Motsinger claims Bill drugged and raped her in 1972. In the case, Bill admitted during a deposition that he obtained a recreational prescription for Quaaludes that he secured from a gynecologist at a poker game.

TMZ.com

Bill also said he planned to use the pills to give to women in the hopes of having sex with them.

Motsinger alleged Bill gave her a pill that she thought was aspirin. She claimed she felt off after taking it and said she woke up the next day in her bed with only her underwear on.

Here, it sounds like Motsinger wants to play the deposition for the jury.

Lifestyle

Baz Luhrmann will make you fall in love with Elvis Presley

Elvis Presley in Las Vegas in Aug. 1970.

NEON

hide caption

toggle caption

NEON

“You are my favorite customer,” Baz Luhrmann tells me on a recent Zoom call from the sunny Chateau Marmont in Hollywood. The director is on a worldwide blitz to promote his new film, EPiC: Elvis Presley in Concert — which opens wide this week — and he says this, not to flatter me, but because I’ve just called his film a miracle.

See, I’ve never cared a lick about Elvis Presley, who would have turned 91 in January, had he not died in 1977 at the age of 42. Never had an inkling to listen to his music, never seen any of his films, never been interested in researching his life or work. For this millennial, Presley was a fossilized, mummified relic from prehistory — like a woolly mammoth stuck in the La Brea Tar Pits — and I was mostly indifferent about seeing 1970s concert footage when I sat down for an early IMAX screening of EPiC.

By the end of its rollicking, exhilarating 90 minutes, I turned to my wife and said, “I think I’m in love with Elvis Presley.”

“I’m not trying to sell Elvis,” Luhrmann clarifies. “But I do think that the most gratifying thing is when someone like you has the experience you’ve had.”

Elvis made much more of an imprint on a young Luhrmann; he watched the King’s movies while growing up in New South Wales, Australia in the 1960s, and he stepped to 1972’s “Burning Love” as a young ballroom dancer. But then, like so many others, he left Elvis behind. As a teenager, “I was more Bowie and, you know, new wave and Elton and all those kinds of musical icons,” he says. “I became a big opera buff.”

Luhrmann only returned to the King when he decided to make a movie that would take a sweeping look at America in the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s — which became his 2022 dramatized feature, Elvis, starring Austin Butler. That film, told in the bedazzled, kaleidoscopic style that Luhrmann is famous for, cast Presley as a tragic figure; it was framed and narrated by Presley’s notorious manager, Colonel Tom Parker, portrayed by a conniving and heavily made-up Tom Hanks. The dark clouds of business exploitation, the perils of fame, and an early demise hang over the singer’s heady rise and fall.

It was a divisive movie. Some praised Butler’s transformative performance and the director’s ravishing style; others experienced it as a nauseating 2.5-hour trailer. Reviewing it for Fresh Air, Justin Chang said that “Luhrmann’s flair for spectacle tends to overwhelm his basic story sense,” and found the framing device around Col. Parker (and Hanks’ “uncharacteristically grating” acting) to be a fatal flaw.

Personally, I thought it was the greatest thing Luhrmann had ever made, a perfect match between subject and filmmaker. It reminded me of Oliver Stone’s breathless, Shakespearean tragedy about Richard Nixon (1995’s Nixon), itself an underrated masterpiece. Yet somehow, even for me, it failed to light a fire of interest in Presley himself — and by design, I now realize after seeing EPiC, it omitted at least one major aspect of Elvis’ appeal: the man was charmingly, endearingly funny.

As seen in Luhrmann’s new documentary, on stage, in the midst of a serious song, Elvis will pull a face, or ad lib a line about his suit being too tight to get on his knees, or sing for a while with a bra (which has been flung from the audience) draped over his head. He’s constantly laughing and ribbing and keeping his musicians, and himself, entertained. If Elvis was a tragedy, EPiC is a romantic comedy — and Presley’s seduction of us, the audience, is utterly irresistible.

Unearthing old concert footage

It was in the process of making Elvis that Luhrmann discovered dozens of long-rumored concert footage tapes in a Kansas salt mine, where Warner Bros. stores some of their film archives. Working with Peter Jackson’s team at the post-production facility Park Road Post, who did the miraculous restoration of Beatles rehearsal footage for Jackson’s 2021 Disney+ series, Get Back, they burnished 50-plus hours of 55-year-old celluloid into an eye-popping sheen with enough visual fidelity to fill an IMAX screen. In doing so, they resurrected a woolly mammoth. The film — which is a creative amalgamation of takes from rehearsals and concerts that span from 1970 to 1972 — places the viewer so close to the action that we can viscerally feel the thumping of the bass and almost sense that we’ll get flecked with the sweat dripping off Presley’s face.

This footage was originally shot for the 1970 concert film Elvis: That’s The Way It Is, and its 1972 sequel, Elvis on Tour, which explains why these concerts were shot like a Hollywood feature: wide shots on anamorphic 35mm and with giant, ultra-bright Klieg lights — which, Luhrmann explains, “are really disturbing. So [Elvis] was very apologetic to the audience, because the audience felt a bit more self conscious than they would have been at a normal show. They were actually making a movie, they weren’t just shooting a concert.”

Luhrmann chose to leave in many shots where camera operators can be seen running around with their 16mm cameras for close-ups, “like they’re in the Vietnam War trying to get the best angles,” because we live in an era where we’re used to seeing cameras everywhere and Luhrmann felt none of the original directors’ concern about breaking the illusion. Those extreme close-ups, which were achieved by operators doing math and manually pulling focus, allow us to see even the pores on Presley’s skin — now projected onto a screen the size of two buildings.

The sweat that comes out of those pores is practically a character in the film. Luhrmann marvels at how much Presley gave in every single rehearsal and every single concert performance. Beyond the fact that “he must have superhuman strength,” Luhrmann says, “He becomes the music. He doesn’t mark stuff. He just becomes the music, and then no one knows what he’s going to do. The band do not know what he’s going to do, so they have to keep their eyes on him all the time. They don’t know how many rounds he’s going to do in ‘Suspicious Minds.’ You know, he conducts them with his entire being — and that’s what makes him unique.”

Elvis Presley in Las Vegas in Aug. 1970.

NEON

hide caption

toggle caption

NEON

It’s not the only thing. The revivified concerts in EPiC are a potent argument that Elvis wasn’t just a superior live performer to the Beatles (who supplanted him as the kings of pop culture in the 1960s), but possibly the greatest live performer of all time. His sensual, magmatic charisma on stage, the way he conducts the large band and choir, the control he has over that godlike gospel voice, and the sorcerer’s power he has to hold an entire audience in the palm of his hands (and often to kiss many of its women on the lips) all come across with stunning, electrifying urgency.

Shaking off the rust and building a “dreamscape”

The fact that, on top of it all, he is effortlessly funny and goofy is, in Luhrmann’s mind, essential to the magic of Elvis. While researching for Elvis, he came to appreciate how insecure Presley was as a kid — growing up as the only white boy in a poor Black neighborhood, and seeing his father thrown into jail for passing a bad check. “Inside, he felt very less-than,” says Luhrmann, “but he grows up into a physical Greek god. I mean, we’ve forgotten how beautiful he was. You see it in the movie; he is a beautiful looking human being. And then he moves. And he doesn’t learn dance steps — he just manifests that movement. And then he’s got the voice of Orpheus, and he can take a song like ‘Bridge Over Troubled Water’ and make it into a gospel power ballad.

“So he’s like a spiritual being. And I think he’s imposing. So the goofiness, the humor is about disarming people, making them get past the image — like he says — and see the man. That’s my own theory.”

Elvis has often been second-classed in the annals of American music because he didn’t write his own songs, but Luhrmann insists that interpretation is its own invaluable art form. “Orpheus interpreted the music as well,” the director says.

In this way — as in their shared maximalist, cape-and-rhinestones style — Luhrmann and Elvis are a match made in Graceland. Whether he’s remixing Shakespeare as a ’90s punk music video in Romeo + Juliet or adding hip-hop beats to The Great Gatsby, Luhrmann is an artist who loves to take what was vibrantly, shockingly new in another century and make it so again.

Elvis Presley in Las Vegas in Aug. 1970.

NEON

hide caption

toggle caption

NEON

Luhrmann says he likes to take classic work and “shake off the rust and go, Well, when it was written, it wasn’t classical. When it was created, it was pop, it was modern, it was in the moment. That’s what I try and do.”

To that end, he conceived EPiC as “an imagined concert,” liberally building sequences from various nights, sometimes inserting rehearsal takes into a stage performance (ecstatically so in the song “Polk Salad Annie”), and adding new musical layers to some of the songs. Working with his music producer, Jamieson Shaw, he backed the King’s vocals on “Oh Happy Day” with a new recording of a Black gospel choir in Nashville. “So that’s an imaginative leap,” says Luhrmann. “It’s kind of a dreamscape.”

On some tracks, like “Burning Love,” new string arrangements give the live performances extra verve and cinematic depth. Luhrmann and his music team also radically remixed multiple Elvis songs into a new number, “A Change of Reality,” which has the King repeatedly asking “Do you miss me?” over a buzzing bass line and a syncopated beat.

I didn’t miss Elvis before I saw EPiC — but after seeing the film twice now, I truly do.

-

World2 days ago

World2 days agoExclusive: DeepSeek withholds latest AI model from US chipmakers including Nvidia, sources say

-

Massachusetts3 days ago

Massachusetts3 days agoMother and daughter injured in Taunton house explosion

-

Montana1 week ago

Montana1 week ago2026 MHSA Montana Wrestling State Championship Brackets And Results – FloWrestling

-

Louisiana5 days ago

Louisiana5 days agoWildfire near Gum Swamp Road in Livingston Parish now under control; more than 200 acres burned

-

Denver, CO2 days ago

Denver, CO2 days ago10 acres charred, 5 injured in Thornton grass fire, evacuation orders lifted

-

Technology7 days ago

Technology7 days agoYouTube TV billing scam emails are hitting inboxes

-

Technology7 days ago

Technology7 days agoStellantis is in a crisis of its own making

-

Politics7 days ago

Politics7 days agoOpenAI didn’t contact police despite employees flagging mass shooter’s concerning chatbot interactions: REPORT