Lifestyle

Incredible Videos Capture Meteor Burning Up Over European Skies

Lifestyle

Pioneering stuntwoman Jeannie Epper, of 'Wonder Woman' and 'Charlie's Angels' dies

Jeannie Epper accepting a Lifetime Achievement Award at the Taurus World Stunt Awards in 2007.

M. Phillips/WireImage/Getty

hide caption

toggle caption

M. Phillips/WireImage/Getty

Jeannie Epper accepting a Lifetime Achievement Award at the Taurus World Stunt Awards in 2007.

M. Phillips/WireImage/Getty

In the 1970’s, when Wonder Woman, the Bionic Woman or one of Charlie’s Angels outran villains, crashed through windows, and leaped over obstacles, viewers were really watching Jeannie Epper, dressed up as a superhero. The groundbreaking Hollywood stuntwoman’s career lasted more 70 years, across more than 150 films and TV shows. Epper passed away of natural causes at her home in Simi Valley, California on Sunday. She was 83 years old.

“As stuntwomen, we all descend from this lineage of stuntwomen such as Jeannie,” says Katie Rowe, president of the Stuntwomen’s Association of Motion Pictures, which Epper co-founded in 1967. “Back in the day, men used to do all the stunts — and they’d throw wigs on them, and dresses. But of course…they don’t move like women. So the women decided to get in on this whole racket. And here we are today.”

Epper began her career at age nine, in the 1951 film Elopement. After her parents sent her to Swiss finishing school, she returned to Hollywood for bit parts in the John Ford movie Cheyenne Autumn and the TV show The Big Valley. But in the late 1970’s, she found more opportunities, when women were given more action-oriented roles. She doubled for Lindsay Wagner on TV’s Bionic Woman, and for Kate Jackson on the TV series Charlie’s Angels. Her breakthrough role was as Lynda Carter’s main stunt double on the TV show Wonder Woman.

“She was always there on this set with me, whenever I had a stunt day,” Carter told NPR. “She did all the hard stuff. She set the standard for everyone else. She was the ultimate professional.”

I have a lot to say about Jeannie Epper. Most of all, I loved her. I always felt that we understood and appreciated one another.

After all, it was the 70s. We were united in the way that women had to be in order to thrive in a man’s world, through mutual respect, intellect and… pic.twitter.com/ghxY2JT5UP

— Lynda Carter (@RealLyndaCarter) May 6, 2024

Carter says the production initially cast a stunt man as her double. “They put a guy with a hairy chest in a Wonder Woman costume — a man with a square, chunky body,” she recalls. “You couldn’t get the camera far enough to know that it wasn’t a woman’s body with zero curves, just hairy arms and hairy armpits, and it just wasn’t gonna work.” Carter says they brought in Jeannie Epper, “and it was perfect.”

Carter says her double was an expert at horseback riding, and for other stunts, Epper trained or helped find other stuntwomen to do high falls, ride motorcycles, perform martial arts or do whatever was necessary for the scene. Back then, she says, the stunts were practical, without post-production effects such as CGI or A.I.

Entertainment Weekly once called Epper “the greatest stuntwoman who ever lived.” She came from a family dynasty of stunt performers. In fact, according to The Hollywood Reporter, director Steven Spielberg called them “Flying Wallendas of film,” comparing them to the famous circus family. Her father John Epper had been a stunt double for actors Gary Cooper, Errol Flynn and Ronald Reagan. Her sisters and brothers, Tony, Margo, Gary, Andy and Stephanie also worked in stunts. Her children and grandchildren have continued in her footsteps.

Epper had a long list of credits; She did cat fights on the soap opera Dynasty and tumbled down a mudslide for Kathleen Turner in Romancing the Stone. She did the stunt driving for Shirley MacLaine in the Oscar-winning 1983 film Terms of Endearment. She also did stunts in such films as Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Minority Report, and more recently, The Fast and the Furious: Tokyo Drift and The Amazing Spider-Man.

Over the years, Epper did get hurt a few times on set, as she told Dan Rather in 1979 on CBS Sunday Morning. She was trapped in a burning cabin for the TV show Lancer, and she was smashed on the head with a heavy picture frame in the movie Foxy Brown. But for the most part, Epper avoided any serious injuries.

Rowe says Epper always regaled others on set with stories about making movies, and gently offered advice. And even in her later years, Epper continued working. “She’d be the grandma you saw on TV that got knocked down in the grocery store,” says Rowe. “She had a long and varied career and she was tough as nails…she was just a hoot. “

Carter called Epper a real-life Wonder Woman. “When you accomplish, with grace and honor, like she did,” she said, “That is the pulse factor of a Wonder Woman, someone that reaches out to help others, to include others, to change the world around them, in small and large ways.”

Lifestyle

Rumor About Universal Music Group Mediating Drake & Kendrick Beef Not True

There’s a rumor going around that Drake and Kendrick Lamar‘s shared music label tried to force them to squash their beef — but turns out, it’s totally unfounded … TMZ has learned.

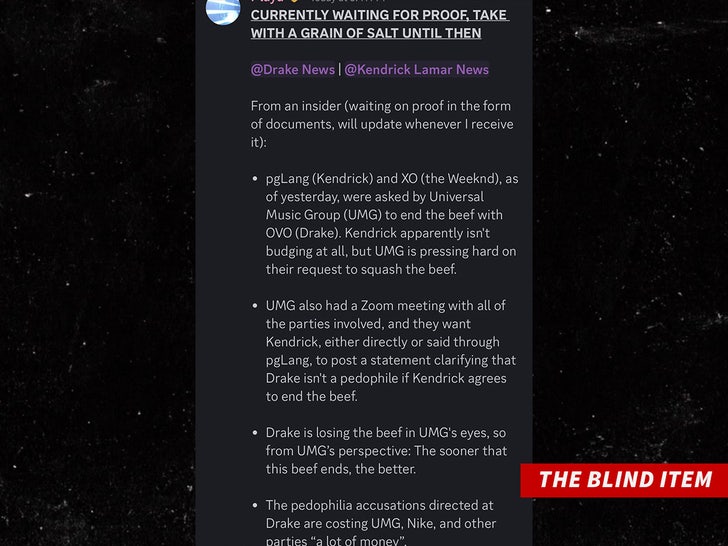

Here’s the deal … a blind item is being circulated that purports to have the inside scoop on an alleged meeting between Kendrick, Drake and Universal Music Group … which both artists are technically signed to via distribution subsidiaries.

There’s a few bullet points addressed in the blind item — including the claim that UMG honchos tried to force Kendrick to capitulate to Drake and apologize and squash things.

The blind item — citing purported insiders — said UMG wanted to have K.Dot put out a statement acknowledging that Drake is not, in fact, a pedophile … this while alleging that UMG brass was viewing Drake as losing big time in the beef and it hurting their bottom line.

It also sounded pretty thorough and detailed … but sources with direct knowledge tell TMZ there was no such meeting between UMG, Drake and Kendrick … and that this entire little narrative — which is starting to go viral online — is completely made up and not true.

We’re told not only did UMG not insert itself here … but our sources, who are familiar with the inner workings of the label, say Universal would never jump into something like this.

The way it was explained to us … Kendrick and Drake’s beef is between them and completely separate from the business side of things — and UMG just doesn’t think it’s their place to step in either way. So, they didn’t … nor did they ever consider doing so.

Mind you, there’s also the fact that all these music drops have clearly only helped them. All the tracks between these two guys have spurred lots of streams and plays — and that’s dollars for UMG … so, objectively, there’s a financial incentive to keep a beef like this going.

Now, in terms of whether it actually will keep going or die on the vine … all signs point to the latter. DJ Hed telegraphed this earlier this week, suggesting Drake was throwing in the towel and moving on. Of course, that was before a shooting took place at Drake’s house.

No telling how the unfortunate development may affect things in the music space — on the issue of either of these titans being brought in by the principal to work out their problems … we’re told it’s complete BS.

Here’s hoping they can work out their issues quietly (and non-violently) behind the scenes.

Lifestyle

'Long Island' renders bare the universality of longing

Sometimes a literary character’s hold on its author (and readers!) is too strong to ignore. While many sequels feel like attempts to milk a cash cow, others, like Elizabeth Strout’s Olive Kitteridge novels, bring fresh delight.

Long Island, Colm Tóibín’s heartrending follow-up to his beloved 2009 novel, Brooklyn, is the rare instance in which a sequel is every bit as good as the original.

Brooklyn, which was further popularized by the eponymous 2015 movie starring Saoirse Ronan, concerns a young Irish immigrant torn between her new home and her old one in the 1950s. Eilis Lacey, recently sent to America by her family for better prospects, returns to Enniscorthy in County Wexford, her hometown and Tóibín’s, for the funeral of her beloved older sister. Her mother, alone now that Rose is dead, doesn’t want Eilis to leave. But Eilis can’t bring herself to tell her — or anyone, including the man with whom she strikes up a romance — that she’s married to an Italian-American plumber she met at a dance in Brooklyn.

Long Island picks up Eilis’ story 25 years later, when she learns that her husband, Tony Fiorello, has impregnated one of his married clients, whose husband has categorically rejected the child. Eilis, too, adamantly refuses to have anything to do with the baby. Tony’s family, who live cheek-by-jowl in a cluster of houses in Lindenhurst, Long Island, have always viewed Eilis as an outsider. To escape the tremendous pressure from them to accept this child, Eilis decides to absent herself when the baby is due by returning to Ireland for the first time in more than 20 years. She arranges for her two teenage children, Rosella and Larry, to join her in time for the 80th birthday of the grandmother they’ve never met.

Everyone in Enniscorthy finds Eilis profoundly changed, “like a different person.” She tells no one why she’s there, including her testy mother, who lets Eilis know how insulting she finds her daughter’s patronizing attempts to fix up her home after such a long absence.

When Eilis stops in to see her former best friend, Nancy Sheridan, widowed for five years, neither woman is open about what’s going on in their lives. Nancy, not wanting to overshadow her daughter’s upcoming wedding, is keeping her impending engagement to Jim Sheridan, the pub owner whom Eilis jilted 25 years ago without an explanation, under wraps for the time being.

Ah, secrets. Tóibín, whose flawless ear captures the constant murmur of gossip that courses through small towns like Enniscorthy, is also sharply attuned to the unspoken. Such circumspection has long underpinned his fiction, including The Master and The Magician, in which he depicted the complicated lives and carefully repressed sexuality of literary titans Henry James and Thomas Mann with graceful nuance.

As always, Tóibín’s narrative restraint heightens tension and allows readers to fill in the blanks. We marvel at his skill as we watch his characters in Long Island become ensnared in the elaborate web of strategically withheld information and calculated partial truths he has them spin.

Long Island shares with The Magician and story collections such as The Empty Family a concern with the pain of the exile’s return after a long absence. But while in Brooklyn, Eilis’ relationships with two very different men separated by thousands of miles underscores the theme of an immigrant uneasily straddling two cultures, Long Island finds her more deeply rooted in America. Anchored by her American children and her bookkeeping job, Eilis’ future wouldn’t be in question if not for the situation with Tony’s baby. Her subsequent return to Ireland causes a pull not between countries but between reason and romance, moral obligations and what the heart desires. Among the many discussion-worthy questions this novel poses: Which is worse, to betray someone, or to betray your feelings?

Tóibín’s portrait of Eilis is sympathetic, both in her youthful dissembling and in her current decisiveness, which borders on intransigence. Long Island finds her not just more mature but more self-assured after decades of marriage, motherhood, and holding her own against her intrusive in-laws. Her imperatives — what she feels she has to do, whether about the unwanted baby or her future — are non-negotiable. When Jim talks about his sadness over her abrupt, hurtful parting years ago, Eilis responds without apparent remorse or sympathy: “It was the way it had to be.” But the changes she is contemplating this time involve many people and “many uncertainties,” which require time to navigate.

Tóibín handles these uncertainties and moral conundrums with exquisite delicacy, zigzagging back and forth through time to build to a devastating climax. The tragedy of this novel about the universality of longing is that, even 25 years on, Eilis, however decisive, is still not in control of her own life.

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoRussian forces gained partial control of Donetsk's Ocheretyne town

-

Movie Reviews1 week ago

Challengers Movie Review

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoDems disagree on whether party has antisemitism problem

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoHouse Republicans brace for spring legislative sprint with one less GOP vote

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoAt least four dead in US after dozens of tornadoes rip through Oklahoma

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoAnti-Trump DA's no-show at debate leaves challenger facing off against empty podium

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoStefanik hits special counsel Jack Smith with ethics complaint, accuses him of election meddling

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoAs student protesters get arrested, they risk being banned from campus too