Lifestyle

How one Mexican immigrant works to honor traditions across borders

Kevin rides a horse as he leads it to the middle of the rodeo to pose for a picture with his maids of honor at his birthday celebration. He’s asked to be identified only by his first name to protect his safety.

Toya Sarno Jordan

hide caption

toggle caption

Toya Sarno Jordan

Kevin is a typical 18-year-old high school teen who loves football, dancing and listening to regional Mexican music superstar Peso Pluma.

His immediate goal is graduating from high school in California, an important milestone since he left Mexico.

His family had faced crime and cartel-driven violence in his native Michoacán. Kevin’s high school was forced to close for several months after frequent shootings and disappearances.

Normal life in his town was suspended.

No one dared to walk outside or gather at night. Kevin says he missed out on many of the freedoms most teenagers long for.

Groups of organized crime like the one that took control over Kevin’s town often recruit young kids and teenagers to work for them, jeopardizing their already vulnerable futures.

Clouds pass over rows of avocado trees in Michoacán. Control of the $3 billion market, known as green gold, has fueled violence in the state who’s the main producer.

Stephania Corpi Arnaud

hide caption

toggle caption

Stephania Corpi Arnaud

Clouds pass over rows of avocado trees in Michoacán. Control of the $3 billion market, known as green gold, has fueled violence in the state who’s the main producer.

Stephania Corpi Arnaud

Kevin walks to the school bus stop in California on June 21, 2022. He loves math and hopes to attend college to study architecture or civil engineering, which would make him the first of his family to go to college.

Toya Sarno Jordan

hide caption

toggle caption

Toya Sarno Jordan

Kevin walks to the school bus stop in California on June 21, 2022. He loves math and hopes to attend college to study architecture or civil engineering, which would make him the first of his family to go to college.

Toya Sarno Jordan

First, a family member was murdered by the cartel controlling his town.

Fearing they’d be next on the hit list, Kevin and his family fled to the U.S. with nothing but a change of clothes.

After a 4-month-long journey to safety, a rare exemption to Title 42 allowed their entry into the U.S. legally. Two years after petitioning for asylum, a lot has changed.

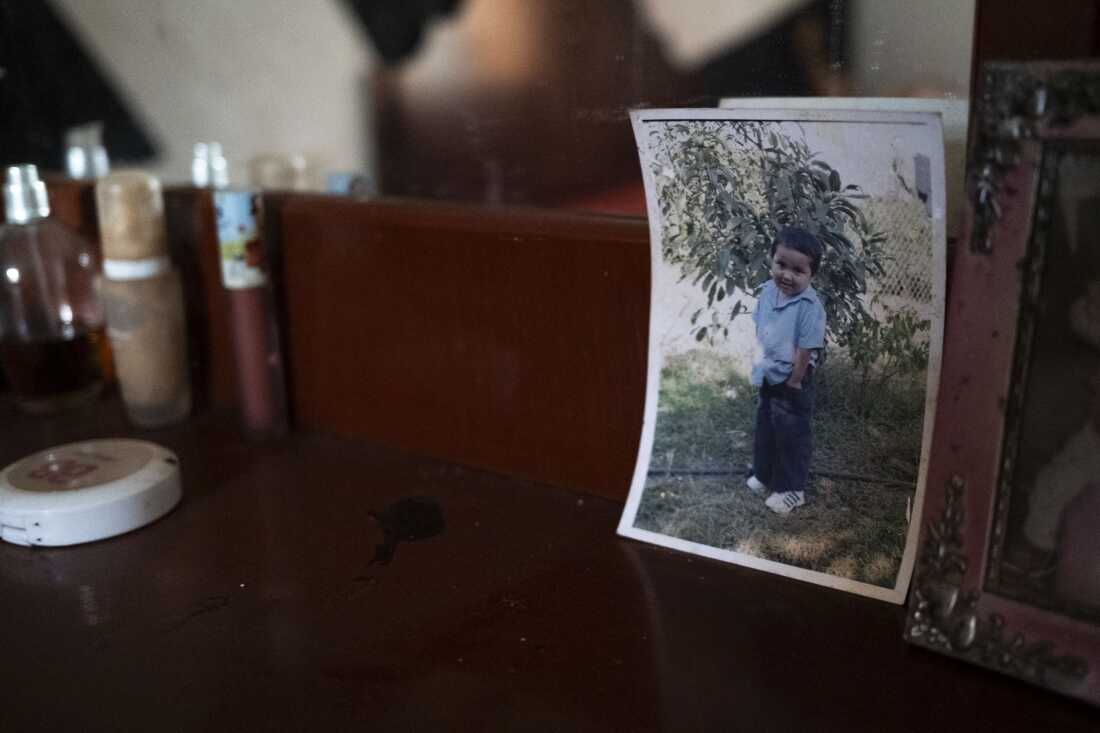

A photo of Kevin as a child stands on a table in his family’s abandoned house in Michoacán, Mexico on November 14, 2022. The house has remained abandoned and all their belongings remain in the same place.

Toya Sarno Jordan

hide caption

toggle caption

Toya Sarno Jordan

Kevin talks with his grandmother during the tacos de carnitas gathering the day after his birthday party. His grandmother came to California for the celebration. Kevin and his family used to share the same house in Michoacán; after they left, his grandfather died of COVID-19.

Stephania Corpi Arnaud

hide caption

toggle caption

Stephania Corpi Arnaud

Kevin talks with his grandmother during the tacos de carnitas gathering the day after his birthday party. His grandmother came to California for the celebration. Kevin and his family used to share the same house in Michoacán; after they left, his grandfather died of COVID-19.

Stephania Corpi Arnaud

Their case is still open, wounds are healing, and the idea of having a life in the U.S. has settled in.

But this life still hinges on a judge’s decision of being granted asylum and the growing backlog of asylum petition cases, which means that migrants such as Kevin might not have a court date in years.

As he waits, Kevin wants to take a moment to celebrate his 18th birthday by bringing together Mexican traditions in a new place he now calls home.

Building a new identity has been a daily effort for Kevin, the eldest child, and his siblings, but he’s thankful for the opportunity of a new life as he navigates a new language, school, friends and becoming an adult.

He’s also able to help his mother to make ends meet by working on weekends deejaying at parties.

Kevin and his maids of honor pose for a portrait outside the church while a band plays regional music for his birthday on June 17, 2023.

Stephania Corpi Arnaud

hide caption

toggle caption

Stephania Corpi Arnaud

Kevin and his maids of honor pose for a portrait outside the church while a band plays regional music for his birthday on June 17, 2023.

Stephania Corpi Arnaud

Linda, Kevin’s mother, prepares a plate of food during Kevin’s birthday party in California on June 17, 2023. Family and friends pitched in for the party supplies: His uncle prepared carnitas estilo Michoacán, his other uncle provided a live band, the cake was a gift, and even the venue and the horses belonged to someone from his community.

Toya Sarno Jordan

hide caption

toggle caption

Toya Sarno Jordan

Linda, Kevin’s mother, prepares a plate of food during Kevin’s birthday party in California on June 17, 2023. Family and friends pitched in for the party supplies: His uncle prepared carnitas estilo Michoacán, his other uncle provided a live band, the cake was a gift, and even the venue and the horses belonged to someone from his community.

Toya Sarno Jordan

A quinceañera celebration is a popular coming-of-age milestone in most Latin cultures. It symbolizes leaving childhood behind, a rite of passage — girls becoming women.

Quinceañera parties are a grandiose celebration for family and friends. The girl is usually escorted by chambelanes, groomsmen with cadet-like costumes who partake in dancing a waltz, a high point of the celebration.

But for men, becoming an adult happens when they turn 18, and it is defined by becoming a protector and provider for their families.

For Kevin, becoming an adult has taken on a new meaning. “I wanted all my guests to see that I haven’t distanced myself from there (Michoacán),” he said as family and friends gathered the next day to enjoy tacos de carnitas, an unofficial after-party for any quinceañera celebration.

This party, beyond being his rite of passage, felt bittersweet, in a moment in life where he was still clinging to his life back in Mexico; he planned a huge party and gathered as many Michoacanos he could invite to feel a resemblance of this past life, many of them also fleeing violence themselves.

Plastic flowers, tickets and garbage in their hometown cemetery in Michoacán, a few days after Day of the Dead celebrations in November 2022.

Stephania Corpi Arnaud

hide caption

toggle caption

Stephania Corpi Arnaud

Plastic flowers, tickets and garbage in their hometown cemetery in Michoacán, a few days after Day of the Dead celebrations in November 2022.

Stephania Corpi Arnaud

Candles of the Mexican Virgin of Guadalupe sit outside the church where Kevin’s Mass took place on June 17, 2023.

Stephania Corpi Arnaud

hide caption

toggle caption

Stephania Corpi Arnaud

Candles of the Mexican Virgin of Guadalupe sit outside the church where Kevin’s Mass took place on June 17, 2023.

Stephania Corpi Arnaud

Kevin’s 18th birthday celebrations included a Catholic ceremony, traditional rehearsed dancing with his maids of honor, three changes of clothes, and even a horse for Kevin to ride, something he longed for, as it is the staple of celebrations in Mexico’s ranching culture.

And everyone pitched in — his uncle prepared carnitas estilo Michoacán, his other uncle provided a live music band, the cake was a gift, and even the venue and the horse belonged to someone from his community.

In the U.S., he’s now surrounded by the possibilities of a better future and dreams of going to college to study architecture, which would make him the first of his family to go to college.

Two girls look on at a horse during Kevin’s birthday party in June 2023.

Toya Sarno Jordan

hide caption

toggle caption

Toya Sarno Jordan

Two girls look on at a horse during Kevin’s birthday party in June 2023.

Toya Sarno Jordan

Carlitos, Kevin’s youngest brother, poses for a portrait at Kevin’s birthday party in June 2023.

Toya Sarno Jordan

hide caption

toggle caption

Toya Sarno Jordan

Carlitos, Kevin’s youngest brother, poses for a portrait at Kevin’s birthday party in June 2023.

Toya Sarno Jordan

California has historically received thousands of immigrants from Michoacán, like the astronaut José Hernández Moreno, but the most recent arrivals are people who have been forcibly displaced due to violence. In January, more than 150 people were murdered in the Mexican state.

The ones who can, flee that state. Many try to get to the U.S. That same month, Customs and Border Patrol processed about 66,000 Mexican migrants at the border.

A family member cleans Kevin’s face after the mordida, a Mexican tradition when the birthday boy or girl’s face is shoved into a cake for them to take the first bite as they’re surrounded by their loved ones chanting Mor-di-da! Mor-di-da!

Stephania Corpi Arnaud

hide caption

toggle caption

Stephania Corpi Arnaud

A family member cleans Kevin’s face after the mordida, a Mexican tradition when the birthday boy or girl’s face is shoved into a cake for them to take the first bite as they’re surrounded by their loved ones chanting Mor-di-da! Mor-di-da!

Stephania Corpi Arnaud

People dance at Kevin’s 18th birthday party. Kevin gathered as many Michoacanos as he could invite in his community in California, many of whom were from the same small avocado-producing town his family had fled after organized crime took control.

Toya Sarno Jordan

hide caption

toggle caption

Toya Sarno Jordan

People dance at Kevin’s 18th birthday party. Kevin gathered as many Michoacanos as he could invite in his community in California, many of whom were from the same small avocado-producing town his family had fled after organized crime took control.

Toya Sarno Jordan

Kevin and his family celebrate and honor their heritage, but their feet and dreams are in the U.S. now.

“I’m still working on [improving] my English, but my Math teacher told me that if I kept getting good grades, she could help me with an application to [attend] a university in San Francisco.”

Kevin and his maids of honor dance the mariachi song “Negrita de mis pesares” at his birthday party in June 2023.

Stephania Corpi Arnaud

hide caption

toggle caption

Stephania Corpi Arnaud

Kevin and his maids of honor dance the mariachi song “Negrita de mis pesares” at his birthday party in June 2023.

Stephania Corpi Arnaud

Kevin rides a horse as he leads it to the middle of the rodeo to pose for a picture with his maids of honor at his birthday celebration. He’s asked to be identified only by his first name to protect his safety.

Stephania Corpi Arnaud

hide caption

toggle caption

Stephania Corpi Arnaud

Kevin rides a horse as he leads it to the middle of the rodeo to pose for a picture with his maids of honor at his birthday celebration. He’s asked to be identified only by his first name to protect his safety.

Stephania Corpi Arnaud

Toya Sarno Jordan and Stephania Corpi Arnaud are documentary photographers based in Mexico City. You can see more of Toya’s work on her website, toyasarnojordan.com, or on Instagram at @toyasjordan. Stephania’s work is available on her website, stephaniacorpi.com , or on Instagram at @s.corpi

Lifestyle

In Brooklyn’s Park Slope neighborhood, children’s entertainment comes with strings

The Tin Soldier, one of Nicolas Coppola’s marionette puppets, is the main character in The Steadfast Tin Soldier show at Coppola’s Puppetworks theater in Brooklyn’s Park Slope neighborhood.

Anh Nguyen for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Anh Nguyen for NPR

Every weekend, at 12:30 or 2:30 p.m., children gather on foam mats and colored blocks to watch wooden renditions of The Tortoise and the Hare, Pinocchio and Aladdin for exactly 45 minutes — the length of one side of a cassette tape. “This isn’t a screen! It’s for reals happenin’ back there!” Alyssa Parkhurst, a 24-year-old puppeteer, says before each show. For most of the theater’s patrons, this is their first experience with live entertainment.

Puppetworks has served Brooklyn’s Park Slope neighborhood for over 30 years. Many of its current regulars are the grandchildren of early patrons of the theater. Its founder and artistic director, 90-year-old Nicolas Coppola, has been a professional puppeteer since 1954.

The Puppetworks theater in Brooklyn’s Park Slope neighborhood.

Anh Nguyen for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Anh Nguyen for NPR

A workshop station behind the stage at Puppetworks, where puppets are stored and repaired.

Anh Nguyen for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Anh Nguyen for NPR

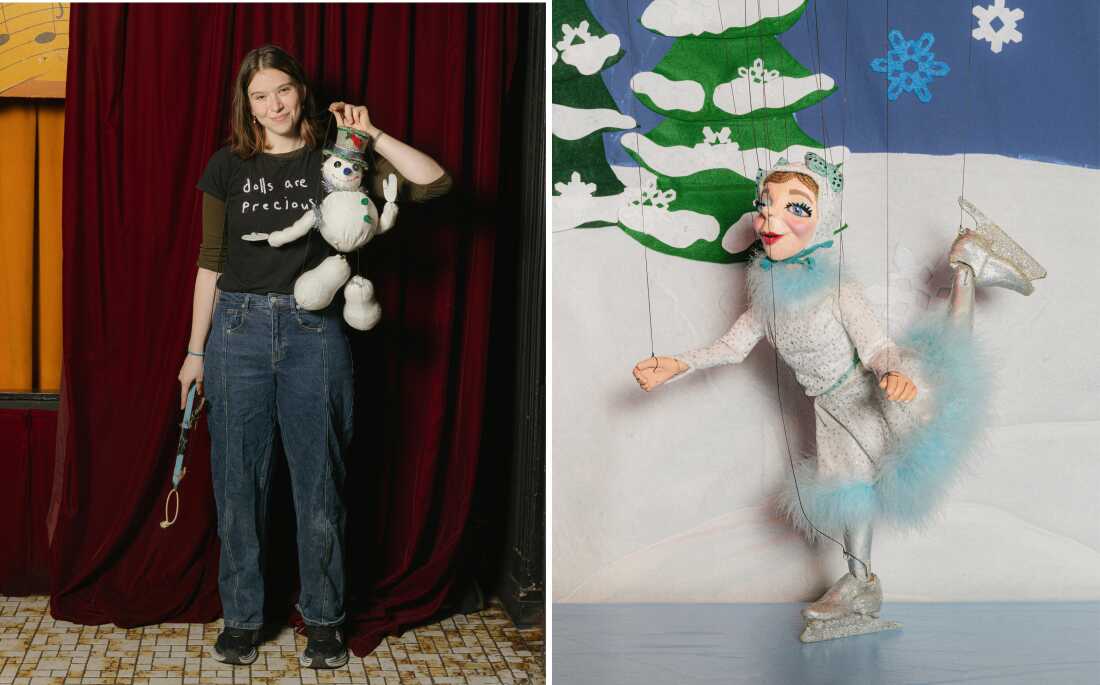

A picture of Nicolas Coppola, Puppetworks’ founder and artistic director, from 1970, in which he’s demonstrating an ice skater marionette puppet.

Anh Nguyen for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Anh Nguyen for NPR

For just $11 a seat ($12 for adults), puppets of all types — marionette, swing, hand and rod — take turns transporting patrons back to the ’80s, when most of Puppetworks’ puppets were made and the audio tracks were taped. Century-old stories are brought back to life. Some even with a modern twist.

Since Coppola started the theater, changes have been made to the theater’s repertoire of shows to better meet the cultural moment. The biggest change was the characterization of princesses in the ’60s and ’70s, Coppola says: “Now, we’re a little more enlightened.”

Right: Michael Jones, Puppetworks’ newest puppeteer, poses for a photo with Jack-a-Napes, one of the main characters in The Steadfast Tin Soldier. Left: A demonstration marionette puppet, used for showing children how movement and control works.

Anh Nguyen for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Anh Nguyen for NPR

Marionette puppets from previous Puppetworks shows hang on one of the theater’s walls.

Anh Nguyen for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Anh Nguyen for NPR

A child attends Puppetworks’ 12:30 p.m. showing on Saturday, Dec. 6, dressed in holiday attire that features the ballerina and tin soldier in The Steadfast Tin Soldier.

Anh Nguyen for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Anh Nguyen for NPR

Streaming has also influenced the theater’s selection of shows. Puppetworks recently brought back Rumpelstiltskin after the tale was repopularized following Dreamworks’ release of the Shrek film franchise.

Most of the parents in attendance find out about the theater through word of mouth or school visits, where Puppetworks’ team puts on shows throughout the week. Many say they take an interest in the establishment for its ability to peel their children away from screens.

Whitney Sprayberry was introduced to Puppetworks by her husband, who grew up in the neighborhood. “My husband and I are both artists, so we much prefer live entertainment. We allow screens, but are mindful of what we’re watching and how often.”

Left: Puppetworks’ current manager of stage operations, Jamie Moore, who joined the team in the early 2000s as a puppeteer, holds an otter hand puppet from their holiday show. Right: A Pinocchio mask hangs behind the ticket booth at Puppetworks’ entrance.

Anh Nguyen for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Anh Nguyen for NPR

A child attends Puppetworks’ 12:30 p.m. showing on Saturday, Dec. 6, dressed in holiday attire.

Anh Nguyen for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Anh Nguyen for NPR

Left: Two gingerbread people, characters in one of Puppetworks’ holiday skits. Right: Ronny Wasserstrom, a swing puppeteer and one of Puppetworks’ first puppeteers, holds a “talking head” puppet he made, wearing matching shirts.

Anh Nguyen for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Anh Nguyen for NPR

Other parents in the audience say they found the theater through one of Ronny Wasserstrom’s shows. Wasserstrom, one of Puppetworks’ first puppeteers, regularly performs for free at a nearby park.

Coppola says he isn’t a Luddite — he’s fascinated by animation’s endless possibilities, but cautions of how it could limit a child’s imagination. “The part of theater they’re not getting by being on the phone is the sense of community. In our small way, we’re keeping that going.”

Puppetworks’ 12:30 p.m. showing of The Steadfast Tin Soldier and The Nutcracker Sweets on Saturday, Dec. 6.

Anh Nguyen for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Anh Nguyen for NPR

Children get a chance to see one of the puppets in The Steadfast Tin Soldier up close after a show.

Anh Nguyen for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Anh Nguyen for NPR

Left: Alyssa Parkhurst, Puppetworks’ youngest puppeteer, holds a snowman marionette puppet, a character in the theater’s holiday show. Right: An ice skater, a dancing character in one of Puppetworks’ holiday skits.

Anh Nguyen for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Anh Nguyen for NPR

Community is what keeps Sabrina Chap, the mother of 4-year-old Vida, a regular at Puppetworks. Every couple of weeks, when Puppetworks puts on a new show, she rallies a large group to attend. “It’s a way I connect all the parents in the neighborhood whose kids go to different schools,” she said. “A lot of these kids live within a block of each other.”

Three candy canes — dancing characters in one of Puppetworks’ holiday skits — wait to be repaired after a show.

Anh Nguyen for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Anh Nguyen for NPR

Anh Nguyen is a photographer based in Brooklyn, N.Y. You can see more of her work online, at nguyenminhanh.com , or on Instagram, at @minhanhnguyenn. Tiffany Ng is a tech and culture writer. Find more of her work on her website, breakfastatmyhouse.com.

Lifestyle

The Best of BoF 2025: Fashion’s Year of Designer Revamps

Lifestyle

Best Christmas gift I ever received : Pop Culture Happy Hour

-

Iowa1 week ago

Iowa1 week agoAddy Brown motivated to step up in Audi Crooks’ absence vs. UNI

-

Maine1 week ago

Maine1 week agoElementary-aged student killed in school bus crash in southern Maine

-

Maryland1 week ago

Maryland1 week agoFrigid temperatures to start the week in Maryland

-

New Mexico1 week ago

New Mexico1 week agoFamily clarifies why they believe missing New Mexico man is dead

-

South Dakota1 week ago

South Dakota1 week agoNature: Snow in South Dakota

-

Detroit, MI1 week ago

Detroit, MI1 week ago‘Love being a pedo’: Metro Detroit doctor, attorney, therapist accused in web of child porn chats

-

Health1 week ago

Health1 week ago‘Aggressive’ new flu variant sweeps globe as doctors warn of severe symptoms

-

Maine1 week ago

Maine1 week agoFamily in Maine host food pantry for deer | Hand Off