Lifestyle

Avoiding your problems with work? You might have “high-functioning” depression

Judith Joseph has spent most of her life building an impressive résumé. She is a board-certified psychiatrist, chair of the Women in Medicine Initiative for Columbia University’s Vagelos College of Physicians & Surgeons, a clinical assistant professor of psychiatry at NYU Langone Medical Center, the principal investigator of her own research lab — and a mom.

But despite her accolades, once the COVID-19 pandemic hit, Joseph couldn’t shake the sense that something was off. With the world on lockdown, Joseph began sharing skits related to her research on social media, many of which went viral. It was only then that she landed on a name to what she, and many others, had been experiencing: high-functioning depression.

Shelf Help is a wellness column where we interview researchers, thinkers and writers about their latest books — all with the aim of learning how to live a more complete life.

“I wanted to make sure that we weren’t just thinking about depression in the way that our grandmothers think of depression, not being able to get out of bed, crying,” Joseph said.

Instead, with high-functioning depression “you push through and you don’t deal with your pain because too many people depend on you,” she said. “You know something’s off, but you can’t quite put your finger on it. And you don’t slow down because you don’t know how to.”

To Joseph’s surprise, high-functioning depression was absent in medical literature. So she set out to design and execute the first research study on the topic, which published in February. Her first book, “High Functioning: Overcome Your Hidden Depression and Find Your Joy” (Little, Brown Spark), relies on findings from the study, anecdotes from patients from her private practice and lessons from her life to teach people how to understand the science of their sadness, so they can understand the science of their happiness.

The Times spoke with Joseph about her book’s findings and why it’s just as important to practice preventative care in mental health as it is in physical health.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Dr. Judith Joseph is the author of “High Functioning: Overcome Your Hidden Depression and Reclaim Your Joy.” (Little, Brown Spark) (Photo by Anthony Steverson)

How would you define high–functioning depression?

With clinical depression, you have five or more symptoms, like low appetite, change in appetite, poor sleep, low energy, feeling restless, guilt, hopelessness, suicidal ideation. But you also have to meet criteria for having a low mood, or anhedonia. And on top of all that, you have to have lower functioning or significant distress.

People with high-functioning depression will have the symptoms of depression, but they’re not low-functioning. In fact, they cope by over-functioning, and they don’t acknowledge having significant distress. In fact, they’re muted. They don’t feel anything.

One of the symptoms of trauma is avoidance. So people think, “OK, I don’t want to go to this place or see this person or be in this situation because it triggers me.” But with high-functioning depression, people are avoiding by busying themselves so they don’t have time to feel, and when they sit still, they feel restless and empty.

A big part of high–functioning depression is being defined by your achievements or what you do for others. Why is it so hard to build identity outside of our external achievements?

Many of us have this coping mechanism of forgetting, and that’s one of the 30-plus symptoms of the trauma inventory. We outrun because we don’t remember what it was like to derive a sense of pleasure from things that truly bring us joy, because our past hides them.

Children, if there’s a conflict, they internalize it and they’ll say, “Well, if I only got straight A’s, Daddy wouldn’t have left.” Or “If I only did my homework, the dog wouldn’t have died.” Children use that magical thinking, but adults use it too. They focus on things like work, a role, on what they can do. In the short run, that’s a positive coping skill, but in the long run, when you continue to intellectualize and you don’t feel, that can show in different ways like binge drinking, excessive shopping, excessive doomscrolling, physical breakdowns or even dipping into low-function depression.

The bottom line is that there is a real value in acknowledging and processing your trauma and healing, because then you can actually experience a change.

“People can search and try to be happy all their lives and never get it. And even if you get the thing you think will make you happy, you’re still not happy. If you shift it, and you’re like, ‘I can increase my points of joy every day,’ then it’s attainable.”

— Dr. Judith Joseph

In the first part of your book, you introduce two key terms: anhedonia and masochism. What is anhedonia and why is it important for people to know what it is?

There’s a real disconnect between the research and the real world, because in research, anhedonia is all over our rating scales. It’s a term that has been around in the medical literature for hundreds of years. “An” is a lack, “hed” is pleasure, and “onia” is a symptom. “Anhedonia” is a lack of pleasure and joy, and it’s a lack of pleasure and joy in things you were once interested in.

So imagine you’re eating your favorite meal and you’re not even tasting it, you’re not savoring it. Or if you are listening to your favorite song, and it doesn’t move your body the way it used to, it doesn’t light you up. Or if you’re looking at a beautiful part of nature, like the sun is setting and it’s exquisite, and you’re just checked out. Or if you’re with your partner, and you’re being intimate and you just want to rush through it; you’re not even in the moment. These are all the simple joys that make life worth living.

In research, you will rarely see the word “happy” on our rating scales, but what you do see are points of joy. Whereas in the real world, the patient will come in and say, “I just want to be happy.” But we’re like, “No, we’re just trying to eradicate your depression by increasing your points of joy.”

Happiness is an idea, whereas joy is an experience. If you can reframe that and think about it as: Anhedonia is robbing [me] of my joy; it’s not that I have to be depressed and weepy and sad, but if my points of joy are low, then that’s an indication that something is off.

It’s a really important shift because people can search and try to be happy all their lives and never get it. And even if you get the thing you think will make you happy, you’re still not happy. If you shift it, and you’re like, I can increase my points of joy every day, then it’s attainable. There’s hope. Today, you may get two points, but tomorrow maybe you get three.

How does masochism contribute to high–functioning depression?

When people think of masochism in the real world, they think of sex, which is not what we’re talking about. We’re talking about masochistic personality disorder. Masochistic traits are ones where people tend to bend over backward for others. They tend to sacrifice their joy for the sake of others. It’s almost like self-sabotaging. In today’s speak, it’s called people-pleasing.

What I found in my study was that a lot of people who are caregivers have high rates of anhedonia. Well, that makes sense. These are people who are not thinking about themselves. They’re putting others first, often at the expense of their own happiness. Because high-functioning depression is closely tied to trauma, and because a symptom of trauma is low self-worth and shame and self-blame, that may be a part of the reason why people with high-functioning depression can’t relax: They’re constantly doing for others.

If you’re someone who knows your self-worth and you know that your role doesn’t define you, you’re not going to bend over backward. You’re not going to keep going, even though you feel off and you feel burned out. You’re going to take care of yourself.

The second half of the book gives the reader concrete steps to reclaim their joy using what you call the Five V’s: validation, venting, values, vitals and vision. How did you develop these five Vs?

If you think about it, there’s been this renaissance in physical health, but there’s nothing for us in mental health. Why do we wait to check that box of low-functioning? We need to show people how to increase their points of joy and prevent these breakdowns on their own.

So, I came up with the five Vs based on what I learned about happiness and research, and derived them based off of things that I felt that people needed to do in order to overcome trauma and how to find sustainable joy.

Validation is the first step. Because many people, again, don’t acknowledge how they feel. They push through pain, they just get through life, and that’s how they cope. But if you can acknowledge how you feel, and accept how you feel, then you could actually do something about it.

Venting is expressing your emotions. Some of my clients are neurodivergent, so they’re not the most verbally expressive. But there are other ways you can vent. You can draw, you can write, you can pray, you can sing. You could talk about your feelings, if that’s how you want to express it. You can cry. Venting has different ways of getting that emotion out and decreasing your stress.

Values are things that, when you tap into them, you feel a sense of purpose and meaning. I would say that values are things that are priceless. Many of us with high-functioning depression, we’re chasing the accolades, and we’re chasing the things that look good on the outside but don’t really give us true meaning.

With Vitals, I wanted to put in the traditional things like sleep, movement and diet, which are all important. But I also wanted to add things like our relationship to technology, our relationships with other people and work-life balance, because the quality of our relationships with people in our lives is the No. 1 predictor of long-term happiness and health.

Vision is how do you plan joy so that you keep moving forward instead of getting stuck in the past? Celebrating your wins so you don’t have to live for tomorrow’s. Start planning joy today. That’s the whole point. Don’t hold your breath for happiness for the future.

(Maggie Chiang / For The Times)

For someone who’s avoidant, it can be really scary to slow down enough to really examine your interior life. What do you say to that person who doesn’t know how to broach the five Vs?

I always say don’t do the five Vs all at once, because people who are intense like myself will want to do everything at once. The goal is not to use all five at once; use one or two. I would say start with validation. It doesn’t have to be this big, grand thing. It could be as simple as looking in the mirror every day and just reflecting on how you feel. Or, if that’s too intense for you, there’s sensory tools like a 5-4-3-2-1 method that is a grounding tool that allows you to be present in your body. Just practice that every day for one to two minutes and, slowly, you should be able to start to self-reflect and acknowledge and accept what you’re feeling and move from there.

You directly tied the idea of “vision” to fostering joy and combating anhedonia. What’s the relationship between vision and anhedonia?

People with high-functioning depression want to keep doing what they’re good at. But it’s important to retrain your brain and slowly reintroduce yourself to the things that you once enjoyed.

For example, in the book I talk about a patient who forgot that they actually enjoyed nature. When they were a child, their parents used to take them camping and when the parents got divorced, they stopped going camping, and they forgot that that’s what they love doing. Now they live in a big city and what they usually do for fun is go see a show or something that is more accessible in a city. But when we identified that trauma, we started to challenge them to go back into nature again. By slowly introducing the person back to the things that they used to like, their anhedonia in relation to nature got better.

TAKEAWAYS

from “High Functioning”

At the end of the book you break down the various types of therapy and drug interventions for someone struggling with their mental health. For someone who has your book in hand and is looking for next steps, what would you recommend them?

I’d recommend for them to take the quizzes [throughout the book] and to see where they are in terms of the levels of anhedonia, depression and trauma and then move from there.

Let’s say, biologically, you’re healthy and psychologically you don’t have very many risk factors. Then you have to work on the social aspect. What is it about you that’s keeping you in that toxic environment? What’s hindering you from leaving there? Because that’s where you’re losing joy.

For another individual, it could be that the social bucket is fine. The psychological bucket is fine. But biologically, maybe there’s an untreated autoimmune issue, or maybe you’re going through perimenopause. Well, then that’s where you need to focus on the science of your happiness.

For others who have trauma that’s never been processed, and they’re constantly in fight or flight, but biologically and socially, things are not as draining for them, then that’s where we need to focus.

There is only ever going to be one you in the history of the universe and in the future of the universe. That, to me, is so powerful because then you know that you’re here for a reason.

So I want people who read this book to really try to understand the science of your happiness, because there’s only one you. And then when you fully understand what’s draining from your happiness, then you can work on those efforts to increase your joy, using the book as a guide.

Shelf Help is a wellness column where we interview researchers, thinkers and writers about their latest books — all with the aim of learning how to live a more complete life. Want to pitch us? Email alyssa.bereznak@latimes.com.

Lifestyle

A wintry mix: 12 reading recommendations to get you through the storm

A woman walks through a snowy street in Manchester in 1939.

Fox Photos/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Fox Photos/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

If you’re hunkering down ahead of the big winter storm this weekend, we want to make sure you’re well prepared. Yes, with batteries, flashlights, toilet paper, and food but — perhaps most importantly — with good reading material.

We looked back through some recent interviews and Books We Love, our annual year-end reading guide, to find snowy suggestions to get you through the storm.

For the nonfiction lovers

Winter: The Story of a Season by Val McDermid, 2026

Scottish author Val McDermid is best known for her crime writing, a world of brutal murders and dark alleyways. But her new book, a work of creative nonfiction, is an ode to memories of winters past and a heartfelt appreciation of all the season has to offer. “I’m kind of hoping it charms you into winter as well,” McDermid told NPR’s Daniel Estrin. Her book meditates on warm soup, and winter festivals, and the comfort of coming indoors on a frigid day. “I like the contrast with being out in the outside, where it’s crisp and cold and when you come indoors and it’s all warm and lovely, and you can sit down with a good book and a good fire or a wee glass of whiskey,” she says. “What’s not to like about that?” — Samantha Balaban, senior producer, Weekend Edition

Ice: From Mixed Drinks to Skating Rinks – a Cool History of a Hot Commodity by Amy Brady, 2023

Amy Brady’s cultural history of ice in America is the unexpected nonfiction pleasure read I turned to in lieu of air conditioning one summer. Brady fascinates and educates, covering the immense impact and complex social histories of this now-ubiquitous and indispensable part of American life. There’s a lot to learn! Helpfully, Ice is divided into four parts: The Birth of an Obsession, Food and Drink, Ice Sports, and The Future of Ice. With clear prose and a lot of passion, Brady touches on many manifestations of ice; however, it feels like just the tip of the iceberg. Do you like surprisingly expansive niche subjects? I can’t recommend this one enough. — Jessica P. Wick, book critic and writer

Wintering: The Power of Rest and Retreat in Difficult Times by Katherine May, 2020

English writer Katherine May’s beautiful and unintentionally but uncannily timely 2020 book is about what she calls “wintering,” a way to weather tough periods when you feel cut off, sidelined or overwhelmed. Brought low by a perfect storm of personal challenges, May learns to slow down, hibernate and regroup. She becomes convinced that the cold has healing powers and explores how other creatures and cultures cope with the dark, frigid season. She takes up ice swimming, cradles an amazingly soft hibernating dormouse and considers the profusion of wolves and snow in fairy tales. May finds solace in her explorations, and readers, especially in these trying times of social distancing, will too. — Heller McAlpin, book critic

For the fiction lovers

The Land in Winter by Andrew Miller, 2025

There’s a storm beneath the somber surface of The Land in Winter, Andrew Miller’s 10th novel. The land is the rural West Country of England during the legendary Big Freeze of the early 1960s, when blizzards engulfed trains on their tracks and froze over rivers. The two young couples who anchor the book are, unsurprisingly, frozen too: a gentleman farmer uneasily married to a former nightclub hostess, and a posh doctor’s wife whose husband is conducting an affair with a patient. The action unfolds like a thaw, and by the end of this Booker-shortlisted novel, it feels as though the drama has soaked itself into your soul. — Neda Ulaby, correspondent, Culture Desk

The Trouble Up North by Travis Mulhauser, 2025

Travis Mulhauser perfectly evoked northern Michigan, in all its beauty and icy menace, in his previous novel, Sweetgirl. He returns to the region in this book, which is just as accomplished as his last. The novel follows a family of bootleggers and smugglers whose criminal enterprise has fallen on tough times, leading one member of the clan to take matters into her own hands. This is a top-notch literary thriller that’s extremely difficult to put down. — Michael Schaub, book critic

The Frozen River by Ariel Lawhon, 2023

Dig your crime novels blanketed with a late 18th-century, New England snow? How about with a capable, middle-aged midwife in the role of detective, telling the men in power things they absolutely do not want to hear? This compelling story begins in a river community in Maine with a body frozen in the ice; it unspools with the alleged assault of a minister’s wife. This is a most uncozy mystery that addresses the unbalanced power dynamics of men and women, rich and poor. Bonus: The character of the midwife and some plot points are based on a real person, Martha Ballard. Not quite true crime but true enough! — Melissa Gray, senior producer, Weekend Edition

Every Reason We Shouldn’t by Sara Fujimura, 2020

Olivia Kennedy is 15 going on 16 and the prodigal daughter of two Olympic figure skating darlings. A gold medal pairs skater at the junior level, Olivia no longer competes due to lack of funds and a crash-and-burn performance when she was 13. But things start looking up when short track speed skater Jonah Choi comes to town. The two bond immediately over mild teenage rebellions, workouts and the concept of being “normal.” They challenge each other because they know no other way – second best is not an option in the life of champions. — Alethea Kontis, author and book critic

Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead: A Novel by Olga Tokarczuk, translated by Antonia Lloyd-Jones, 2019

I originally picked up this book just because of the title. Later, I heard that Olga Tokarczuk had won the (delayed) 2018 Nobel Prize for Literature, and it made total sense because this book (originally published in 2009, released in English translation in 2019) is both deeply strange and deeply personal – a kind of noir murder mystery with feminist, leftist, vegetarian and academic undertones. Gorgeously written and immediately engaging, it is a complicated story about deer, hunters, age, infirmity, chaos and William Blake, driven by the rigorously no-BS practicality of its elderly narrator, Janina Duszejko, who is trying to figure out who is murdering all the hunters in her small, snowbound Polish village, all while contemplating the greater mysteries of life, Poland and the universe in general. — Jason Sheehan, author and book critic

And for the kids …

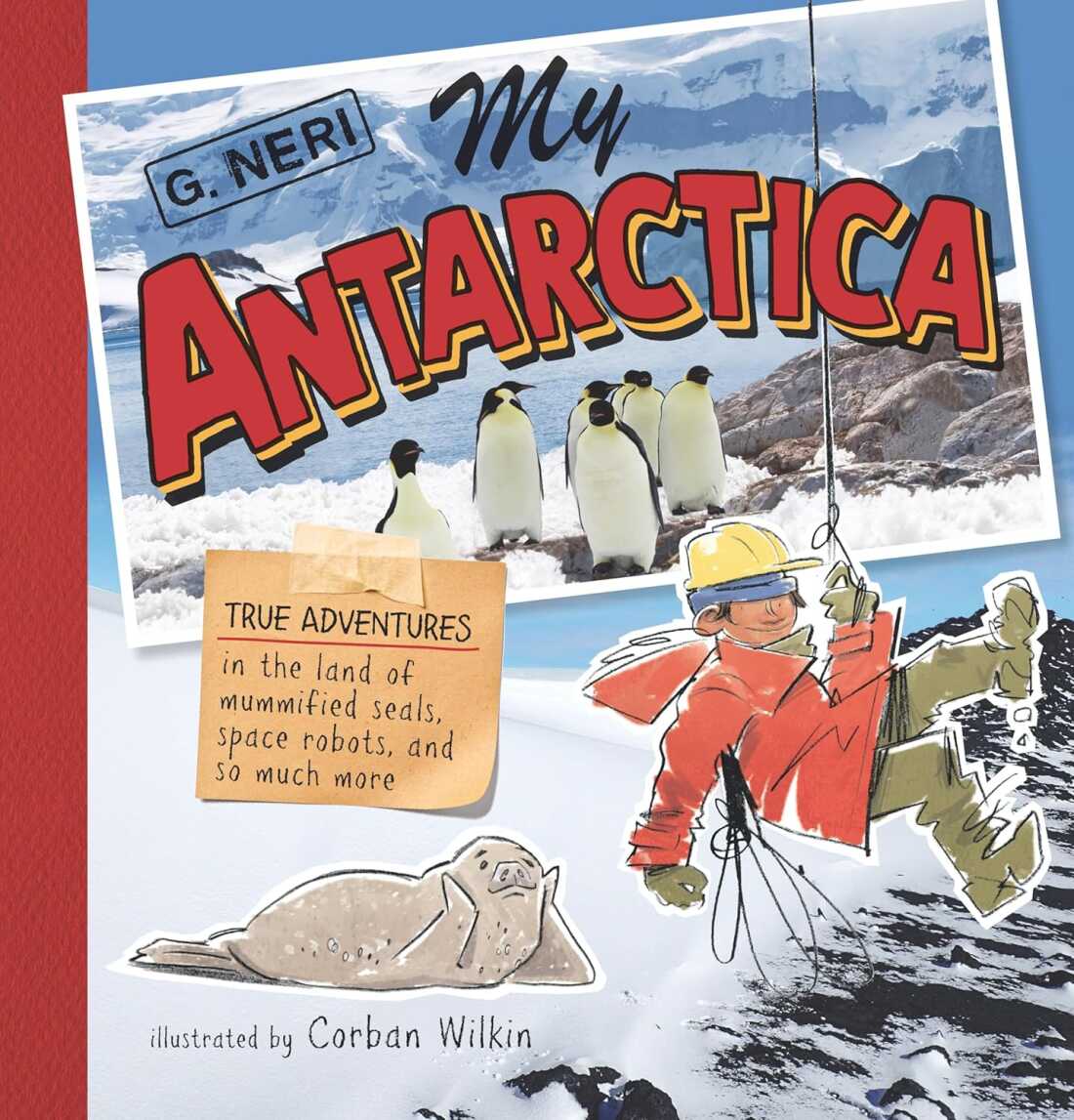

My Antarctica: True Adventures in the Land of Mummified Seals, Space Robots, and So Much More by G. Neri, illustrated by Corban Wilkin, 2024

Take a trip to the coldest, windiest, highest and driest continent in the world. Here, young readers will find answers to every question they’ve ever had about Antarctica – not to mention ones they hadn’t even thought to ask. Who is there now? Why? What do you eat when you’re there? G. Neri’s easygoing narrative reads like a journal, full of cartoons, photos and the occasional mummified seal. Plus, he profiles the many different scientists at work at McMurdo Station with humor, candor and wonder. Just be ready for one inevitable question after reading this book: “Can we go?” (For ages 7 to 10) — Betsy Bird, librarian and author of POP! Goes the Nursery Rhyme

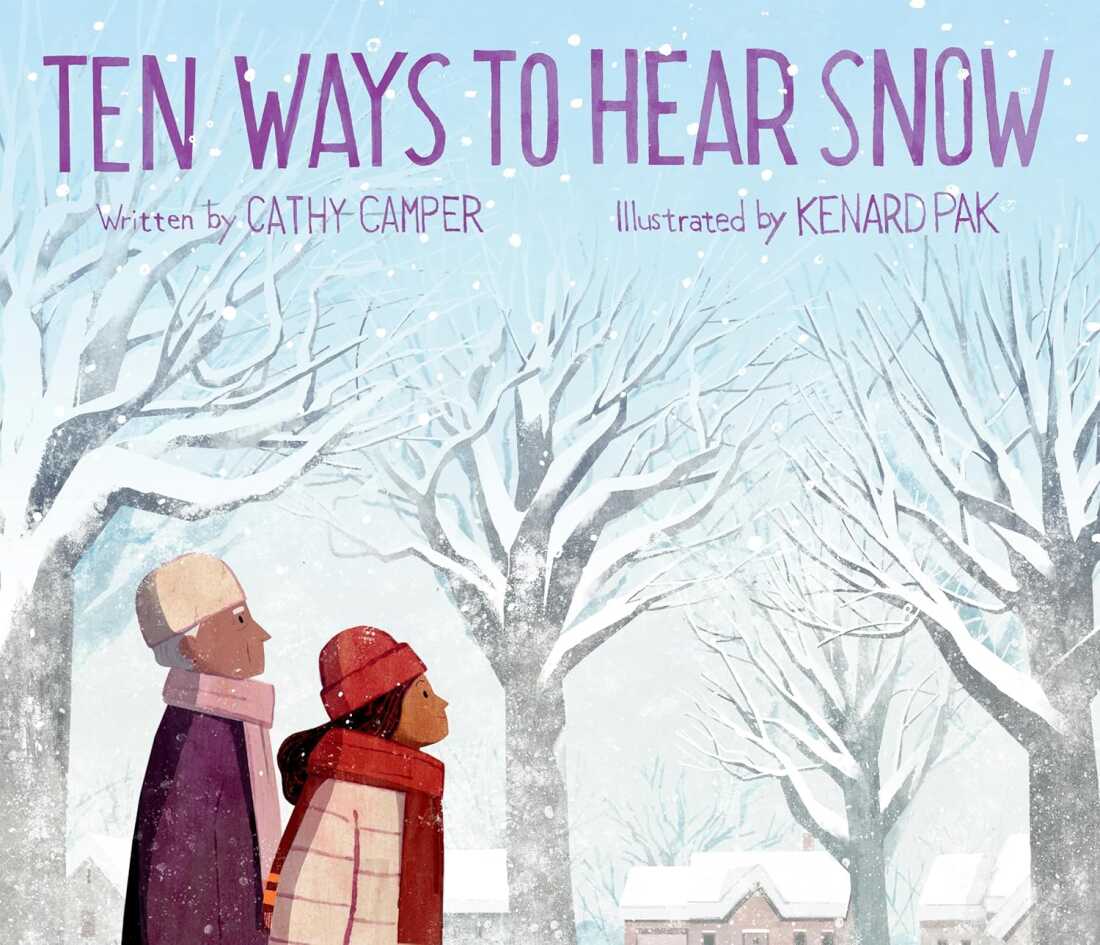

Ten Ways to Hear Snow by Cathy Camper, illustrated by Kenard Pak, 2020

A gentle, affirmative story of a little girl’s winter walk through her neighborhood to visit a beloved grandmother. Lina is Lebanese American, she addresses her grandmother as “Sitti” and the two joyously cook stuffed grape leaves together. But the story’s focus is on Lina’s independence and connection to the sensory magic of a snowy day. Author Cathy Camper humorously evokes the “snyak, snyek, snyuk” of a child’s boots “crunching snow into tiny waffles” and the “scraaape, scrip, scrape” of shovels against the sidewalk. Kenard Pak’s softly saturated watercolors evoke winter’s diffused light and vivid pop of children’s mittens and hats, making cold days something to savor. (For ages 4 to 8) — Neda Ulaby, correspondent, Culture Desk

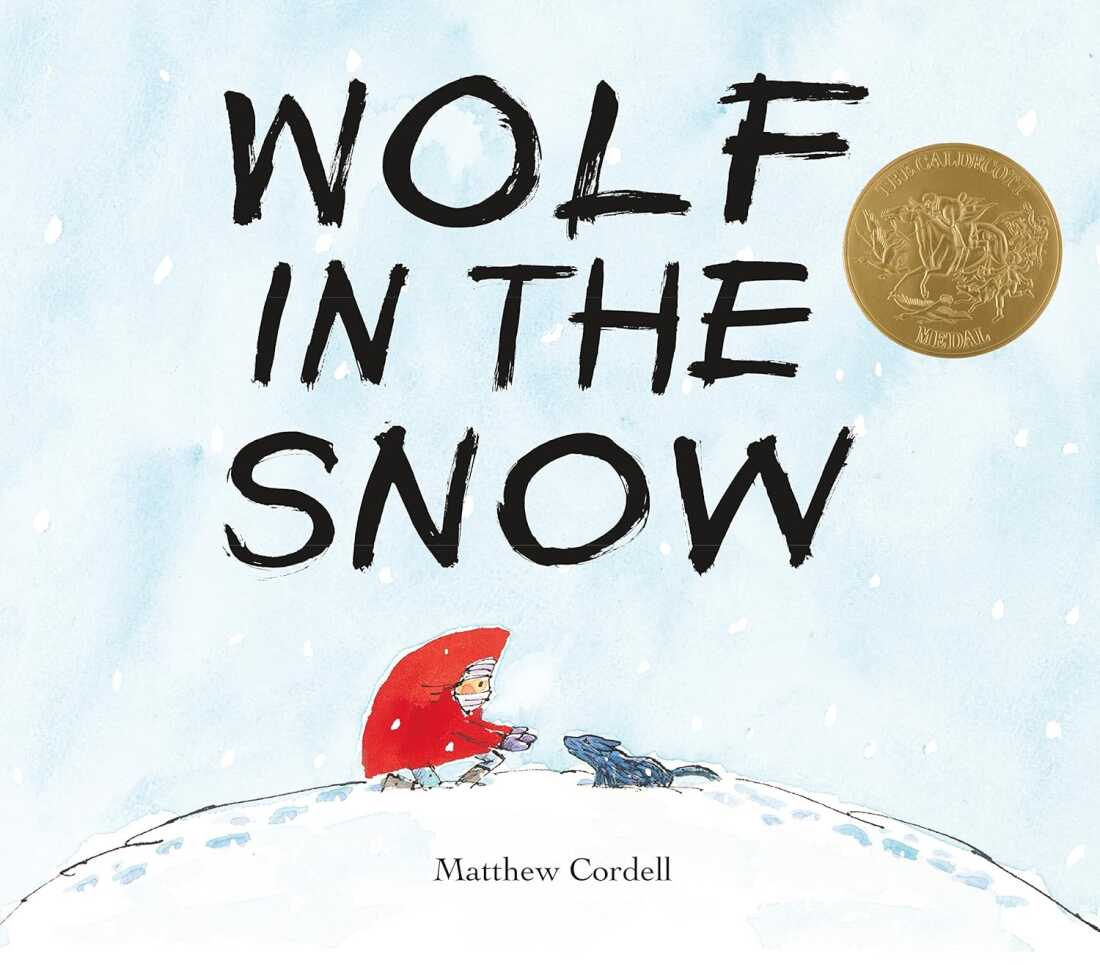

Wolf in the Snow by Matthew Cordell, 2017

As every schoolchild knows, little girls in red-hooded outerwear rarely fare well when encountering wolves in the wild. Yet in this nearly wordless tale, a girl’s meeting with a wayward wolf cub fuels a wary friendship that transcends their very different worlds. From the hyperrealism of the wolves, frightening in their detail, to the sketched-out, almost cartoonish, rendering of the girl, Matthew Cordell offers young readers a dreamy fable with a lot to say about making connections outside your comfort zone. (For ages 4 to 8) — Betsy Bird, librarian and author of POP! Goes the Nursery Rhyme

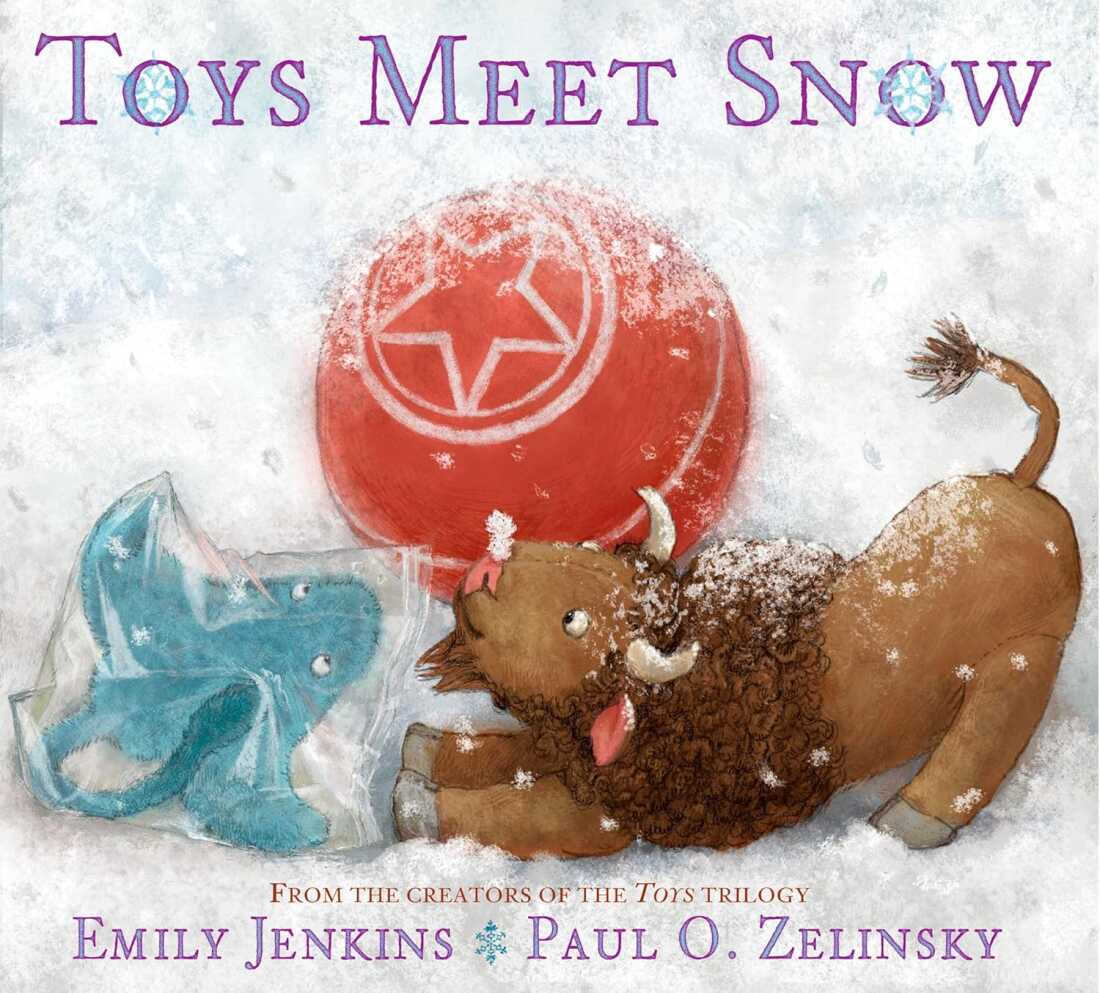

Toys Meet Snow by Emily Jenkins, illustrated by Paul O. Zelinsky, 2015

Whether you’re already acquainted with Lumphy, StingRay and Plastic from their chapter books, or are just meeting them now, you’re sure to love Toys Meet Snow. As the three venture out into the snow for the first time, their unique personalities shine through. Each toy’s impressions and observations are full of imagination and charm. Emily Jenkins’ masterful text is deceptively simple, and Paul O. Zelinsky’s warm and wonderful illustrations make this book an enchanting read for all seasons. (For ages 3 to 7) — Lisa Yee, author of “The Misfits” series

Lifestyle

Couple’s Spa Night Ideas for Valentine’s Day

Set the Mood, Lock the Door💋

Couples Spa Night

Spend V-Day at Home

Published

TMZ may collect a share of sales or other compensation from links on this page.

This Valentine’s Day, skip the impossible reservations and expensive dinners.

Celebrate the love shared with your significant other by hosting the perfect spa night at home. Set the mood with sensual scents and then treat each other to some self care … and maybe a couple’s massage.

From massage oils to mood-setting candles, these indulgent picks turn a quiet night in into an unforgettable Valentine’s experience … no reservations required.

TMZ CHEAT SHEET: COUPLE’S V-DAY AT HOME

Edenika Botanicals Lavender Massage Oil

Get a little closer with your partner by treating them to a steamy spa night at home. Set the mood and unwind with the help of this Edenika Botanicals Lavender Massage Oil.

This calming and relaxing botanical oil’s nourishing formula helps ease stress and tension, and absorbs quickly into the skin. With lavender, bergamot and aloe, it promotes a soothing environment for wherever the night takes you…

Mo Cuishle Shiatsu Back Shoulder and Neck Massager

Reach a new state of relaxation with this Mo Cuishle Shiatsu Back Shoulder and Neck Massager. Whether you want to feel pampered during a Valentine’s Day movie night or are unwinding before bedtime, this portable device is like having a masseuse at home.

With eight kneading massage nodes that utilize Shiatsu-based therapy and infrared heating, your strained muscles will be soothed and your muscle tension will be eased.

Aromatherapy Associates Our Favorite Moments Set

Turn your home into a spa with this Aromatherapy Associates Our Favorite Moments Set. The collection of self-care products has everything you and your partner need for a night of complete relaxation to completely reset and rebalance.

From a bath and shower oil to a de-stressing muscle gel, these luxury products are designed to help you and your loved one find tranquility, achieve a restful night and emerge rejuvenated.

LANEIGE Lip Sleeping Mask

Pucker up! For your most luscious lips ever that your partner can’t resist, you’ll need the LANEIGE Lip Sleeping Mask. A favorite of celebs like Kendall Jenner and Sydney Sweeney, this leave-on lip mask nourishes and hydrates while you catch some z’s, leaving you with smooth and supple looking lips.

Powered by antioxidant rich berry fruit complex, murumuru seed, coconut oil, vitamin c and shea butter. You’ll wake up in the AM feeling refreshed … and with visibly smoother, baby-soft lips.

Mario Badescu Facial Spray

Refresh and hydrate your skin anytime with the iconic Mario Badescu Facial Spray, formulated with aloe, herbs and rose water.

One of Martha Stewart’s beauty must-haves, this rejuvenating mist instantly calms, nourishes and revitalizes, leaving you refreshed all day … or all night. It’s the perfect final step in any skincare routine or spa night experience.

Sign up for Amazon Prime to get the best deals!

All prices subject to change.

Lifestyle

‘Wait Wait’ for January 24, 2026: With Not My Job guest Kevin O’Leary

Canadian businessman and TV personality Kevin O’Leary attends the 83rd annual Golden Globe Awards at the Beverly Hilton hotel in Beverly Hills, California, on January 11, 2026. (Photo by Michael Tran / AFP via Getty Images)

Michael Tran/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Michael Tran/Getty Images

This week’s show was recorded in Chicago with host Peter Sagal, judge and scorekeeper Bill Kurtis, Not My Job guest Kevin O’Leary and panelists Adam Burke, Shantira Jackson, and Mo Rocca. Click the audio link above to hear the whole show.

Who’s Bill This Time

Devastated in Davos; Advances in Beef Technology; An Olympic Pants Scandal

Panel Questions

Houston, I Can’t Find The Remote

Bluff The Listener

Our panelists tell three stories about an innovation in stadiums, only one of which is true.

Not My Job: Shark Tank and Marty Supreme‘s Kevin O’Leary answers answers our questions about the world’s best parties

Star of Shark Tank and Marty Supreme, Kevin O’Leary, plays our game called, “Marty Supreme meet Party Supreme!” Three questions about some of the biggest parties ever.

Panel Questions

Famine Fun For the Whole Family; Cleaning Up Your Aspirations; A New Reason to Avoid the Gym

Limericks

Bill Kurtis reads three news-related limericks: The Panda Diet; Tough Times for Beantown; Getting Rude With Your Home

Lightning Fill In The Blank

All the news we couldn’t fit anywhere else

Predictions

Our panelists predict, now that they can use tools, what’ll be the next surprising thing cows do

-

Sports7 days ago

Sports7 days agoMiami’s Carson Beck turns heads with stunning admission about attending classes as college athlete

-

Illinois3 days ago

Illinois3 days agoIllinois school closings tomorrow: How to check if your school is closed due to extreme cold

-

Pittsburg, PA6 days ago

Pittsburg, PA6 days agoSean McDermott Should Be Steelers Next Head Coach

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoNoem names Charles Wall ICE deputy director following Sheahan resignation

-

Lifestyle6 days ago

Lifestyle6 days agoNick Fuentes & Andrew Tate Party to Kanye’s Banned ‘Heil Hitler’

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoCasting is dead. Long live casting!

-

Sports5 days ago

Sports5 days agoMiami star throws punch at Indiana player after national championship loss

-

Culture1 week ago

Culture1 week agoWhat Kind of Lover Are You? This William Blake Poem Might Have the Answer.