Lifestyle

Aubrey O'Day Claims Diddy Wanted to Buy Silence in Return for Publishing Rights

TMZ Studios

Aubrey O’Day claims Diddy was trying to buy her and other ex-Bad Boy artists’ silence when he gave back their publishing rights … which she says weren’t worth jack.

We talked to the Danity Kane singer — who was signed to Bad Boy Records in the 2000s — as part of a new TMZ doc that’ll be on Tubi Sunday … ‘The Downfall of Diddy,’ which dissects the fallout after the raids on Diddy’s homes, and the federal investigation that followed.

AOD provided some fascinating insight — including the fact she knew what was up back in September … when Puff gave all his old artists the rights to their music. The seemingly generous move came with lots of strings attached, according to Aubrey.

TMZ Studios

You’ll recall … Diddy made a big announcement at the time, saying all the old Bad Boy artists were gonna get what was theirs … as it was the right and noble thing to do, etc.

However, behind the scenes … Aubrey claims Diddy wanted the artists to sign NDAs as part of the deal, which would’ve muzzled them from speaking on their experiences at Bad Boy.

Aubrey says she didn’t want to do that … ’cause she sensed she’d be signing away her ability to speak — something she finds incredibly valuable now, especially in light of everything that’s been alleged against Diddy … by Cassie and others, which he’s denied. BTW … Aubrey is the first and only person who publicly sounded the alarm for years.

There’s also this … Aubrey says the dollar amount attached to getting her publishing rights back was incredibly low. Take a listen … it’s astonishing, if true.

The other reason Aubrey turned down Diddy’s offer for the publishing rights … she’s making a boatload of cash on her own, and doesn’t need the pennies. Aubrey has dipped her toe into multiple ventures … including OnlyFans, which has proven to be very lucrative.

She’s got a lot more to say, all of which will be revealed in the doc, “TMZ Presents: The Downfall of Diddy”, streaming on Tubi. Catch it then!

Lifestyle

My Octopus Teacher's Craig Foster dives into the ocean again in 'Amphibious Soul'

The film My Octopus Teacher tells the story of a man who goes diving every day into the underwater South African kelp forest and forms a close relationship there with an octopus. That man — the diver, and also the filmmaker — was Craig Foster, who delighted millions of nature lovers around the world and took home the 2021 Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature.

Now in a new book, Amphibious Soul: Finding the Wild in a Tame World, Foster describes the entire ecosystem of the Great African Seaforest at the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa, and the transforming role it has played in his quest to seek wildness. As the book’s amphibious title hints, Foster is as much (maybe more) at home in the ocean as he is on land.

Foster’s incredible engagement with seaforest creatures comes through beautifully in this account. Every day for months, he recounts, he “visited the crack in the rock where a huge male clingfish lived,” and the fish became quite calm in his presence. “Returning to the same places, watching for subtle changes, and continuing to ask questions replenishes my curiosity,” he writes.

Foster’s profound tie to place reminds me of birders who closely attend to nature in their own yard or local park. Indeed, Foster underscores that any of us can find wildness where we live: “We can all develop a more playful relationship with nature, whether that means collecting crisp leaves or smooth rocks to use in our artwork or watching the squirrel perform acrobatics outside our window.”

Nature’s healing power is a focus for Foster and an immensely personal one. Before he had any thoughts of My Octopus Teacher, he was burned out on long grinding hours of film-making work. He found relief in cold immersion, both in the ocean and in a home-made box containing icewater. Later though, after the immense global attention to the octopus film and therefore to him, he suffered from insomnia so pronounced that some nights he managed only 10 minutes of sleep. His body and mind were breaking down and felt a strong pull to find his way back to the wild.

To become fully immersed in the story of his quest for wild healing, it’s necessary to go with Foster’s flow and accept his constant, near-mystical reverence for “our ancestors.” I read with a wild-seeking heart his belief that modern-day humans can recover an ancestral link to wild creatures — but also, inescapably, I read with an anthropologist’s sensibilities. Is it possible to replicate “humanity’s natural state?” Is there a singular way to describe our ancestors’ experiences with animals? Given the long sweep of human evolution, which ancestors exactly?

Might there be a hint of romanticizing the past here? Foster writes of “our nonviolent origins” and adds that it was “only with the advent of agriculture that the reciprocity with the wild that we’d enjoyed for some 300,000 years began to break apart — and with it, our psyches.” Yet there’s serious anthropological scholarship that argues warfare began 200,000 or 300,000 years ago, far longer ago than the start of agriculture around 12,000 years ago.

A stronger thread in the book is the powerful connection to nature that comes with tracking. At first, I thought Foster meant looking only for animal tracks in the dirt, mud, or snow, but his definition is more comprehensive, and eye-opening: “any clue left by any creature or plant, sand or rock.” Running water also may leave a track, or lightning hitting a tree.

For an amphibious soul, the height of joy comes with underwater tracking: Foster taught himself to see tracks of mollusks in the sand atop the back of a stingray, or an octopus’s predation marks on a shell. How magnificent to see the undersea universe in such detail! Once again, Foster broadens out from his own experience to encourage the rest of us: “Just start small and chip away,” Foster advises. In addition to looking for ground tracks, “seek out marks on plants, trees, rocks, or walls.”

Foster’s writing is rooted in his own learning from an array of mentors, including Indigenous individuals, and in a wish to share and spread his joy in nature. A spirit of generosity suffuses the book.

It’s probably thanks to an octopus that Amphibious Soul is out in the world. Foster invites us now to recognize the intrinsic value of the Great African Seaforest ecosystem as a whole — and of all ecosystems that enshrine wildness.

Barbara J. King is a biological anthropologist emerita at William & Mary. After writing about animal grief and love, and how all of us may bring about greater compassion for animals, she is now writing about cats for her 8th book. Find her on X, formerly Twitter @bjkingape

Lifestyle

Sage Against the Machine is how L.A.'s native plant nerds release their rage

In a cavernous convention hall in Northern California, at the end of a long, loooong day of important, yes, but eventually mind-numbing presentations about native plants, nearly 200 scientists, botanists and students had had enough. It was pushing 9 p.m. and everyone, exhausted from paying attention, was edging toward the doors and the beckoning bars. That’s when six native-plant nerds took the stage, plugged in their musical instruments and sonically set the room on fire.

L.A.-based band Sage Against the Machine played with a driving, unexpected intensity and enough volume to make your chest hurt in a hard-to-pinpoint style. Was it punk? Rap-metal? Early Doors? Frontman Antonio Sanchez stepped to the microphone in his signature below-the-knee baggy shorts over leggings and monarch-butterfly-wing earring, his head bald save for a slicked-back streak of silver-black hair, and began shouting out lyrics in a blend of caressing wail and shriek.

Crouching and crooning is just one of frontman Antonio Sanchez’s styles, here with lead guitarist Rico Ramirez at one of Sage Against the Machines’ many nursery gigs.

(Michelle Fieler)

Suddenly a rather subdued group of serious academics and researchers at the California Native Plant Society’s 2022 convention in San José turned into a mosh pit of bouncing, frenzied fans, screaming lyrics back at the band and dancing the way people dance when they don’t know any steps but they have to move because they’re too joyously possessed to stand still.

It wasn’t just the throbbing music that hooked them. It was the sly, salty lyrics, full of in-jokes and puns and references only fellow native-plant nerds would understand.

The other day I was watering my lawn

The government told me I was wrong.

They said, “You’re gonna have to turn your irrigation off.”

Sanchez crooned the slow opening to one of the band’s most crowd-pleasing songs, “Kill Your Lawn,” speeding his delivery to squeeze the increasingly complicated lyrics into the meter:

They told me to kill, kill my lawn

But those native plants are such a yawn.

Besides, what am I gonna tell my landscaper, I forgot his name, I think it’s Jose … or, no, no it’s Juan.

What do I tell my landscape designer, I remember his name … his name is Ron,

and what about my landscape architect, he tucks his shirt in, his name is Sean …

Then the music went berserk, and Sanchez and his bandmates were screaming, “I gotta kill my lawn, gotta kill my lawn …” Everyone in the room joined in, jumping and screeching with the chorus: “Kill your lawn!”

Sage Against the Machine members Nicole Calhoun, left, on bass, Rico Ramirez on lead guitar, Hector Cervantes on drums, Jason Suddith on rhythm guitar and Evan Meyer on keyboards are arrayed behind frontman Antonio Sanchez during a performance at the Central Library’s Mark Taper Auditorium in October 2023.

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times)

The gig was cathartic for the audience and a giant high for the band. “After listening [to presentations] all day, it was sweet release,” said drummer Hector Cervantes during a recent interview. “I know it sounds stupid, but that was our Super Bowl, the Super Bowl of plants. And I hope they’ll invite us back for the next convention.” (The convention isn’t scheduled until early 2026, said California Native Plant Society communications director Liv O’Keeffe, “but we definitely want them back.”)

Undoubtedly the band will be there anyway, because the six members of Sage Against the Machine, all huge fans of the ’90s hip-hop, punk, metal, funk and rock band Rage Against the Machine, spend their days working with plants, primarily native plants at some of the most prominent organizations in Southern California.

Sanchez, a former Marine who started the now-defunct Nopalito Native Plant Nursery in Ventura, runs the Santa Monica Mountains Fund Native Plant Nursery in Newbury Park. He founded the band in 2013 with Evan Meyer, executive director of the Theodore Payne Foundation, when the two of them worked for the state’s largest botanic garden devoted to California native plants, Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden in Claremont, now known as California Botanic Garden.

Keyboard player Evan Meyer, co-founder of Sage Against the Machine, with drummer Hector Cervantes during a performance at Rio de Los Angeles State Park in October 2023.

(Rio Asch Phoenix)

Meyer said their first gig was unplanned and totally improvised. He was playing background piano at a garden party when Sanchez came over, sat down beside him and began making up some lyrics. “We were friends. We started freestyling, and people thought it was funny,” Meyer said. “And that’s how it all started. Our first performance was in front of an audience, speaking to people who love plants. It was always meant to be music for our community of plant people.”

Sanchez said they started playing during informal Friday night sessions at the garden “over $1 beers and tacos.” Rico Ramirez, a certified botanist and arborist working for Caltrans, was an intern at the garden then and added his driving lead guitar to the mix. Ramirez’s family is Indigenous Gabrielino Shoshone — his late grandmother, Ya’anna Vera Rocha, was chief of the Gabrielino Shoshone Tribal Nation — and he feels a deep connection to California native plants, especially white sage (Salvia apiana), “our most spiritual plant.” Music has been a priority since he was a child, he said. He’s classically trained in guitar, but his style now is more blues and metal.

Lead guitarist Rico Ramirez. (Kyle Karbowski)

Bass player Nicole Calhoun. (Kyle Karbowski)

“We’re all very serious musicians who, behind the scenes, are entangled in botany and restoration,” Ramirez said. “That’s kind of our passion. We’re playing music to express our passion.”

Eventually all three left the garden but kept playing together sporadically. Sanchez, who was still growing plants on his own, showed up selling plants at Artemisia Native Plant Nursery in El Sereno, which opened in 2018. The owner, Nicole Calhoun, held community events at the nursery “just to let people know we existed.” Sanchez said he had a band, and in April 2019, Calhoun invited the group to perform.

Cervantes, a self-taught drummer and horticulturist working as an agriculture inspector for the Los Angeles County agriculture commissioner, was then working in the native plant section of Descanso Gardens. A colleague invited him to attend the show, and he was intrigued when he heard the band’s name “because I grew up idolizing Rage Against the Machine. Their music had angst, but it was angst toward Mother Earth, a voice for Mother Earth, and right up my alley.”

Backstage at the Mark Taper Auditorium, Sage Against the Machine bandmates Rico Ramirez, left, Nicole Calhoun, Hector Cervantes, Evan Meyer and Antonio Sanchez joke around before they go onstage in October 2023.

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times)

That night was a big turning point. “Hector went up to them after the show and said, ‘You guys need a drummer. Can I join your band?’ And I said, ‘I want to join too,’” said Calhoun, who studied cello in college, “got tapped out with the classical scene” and eventually started playing electric bass for “fun, punk school garage bands.”

About a year later, Sanchez brought an intern at his nursery to practice, Jason Suddith, to play rhythm guitar. And just like that, Sage Against the Machine had six members and a camaraderie that went beyond the music.

“We get on really well, musically and not musically,” said Suddith, who is now the manager of the Arroyo Seco Foundation’s Hahamongna Native Plant Nursery. “People tell us, ‘Oh, you guys sound really good for practicing so infrequently,’ but it comes from a love for each other. We do tend to spend holidays together, with all our families. Even the band wives have their own separate group chat. It’s more than a silly band to us. We’re friends who consider each other like family.”

Rhythm guitarist Jason Suddith at a nursery gig with Sage Against the Machine.

(Michelle Fieler)

But it’s also a way for the group to do a little proselytizing about native plants “and blow off steam too, because we care about the natural world, and it’s being destroyed all the time,” said Calhoun. “We’re trying to rebuild some of those relationships and we give each other strength. It’s important to everyone’s mental and spiritual health. We do a lot of s— talking too, and it feels great to have that release.”

Finding times to practice is challenging. After all, these aren’t teenagers playing in a garage band after school. The band members are in their mid-30s to mid-40s and working full-time jobs. They’re all married or in committed relationships and most have children. Calhoun, whose daughter is 2, is trying to finish a graduate degree in landscape architecture, “so I can take my business a little further.”

Still, they’re all committed to performing, and will release their new album on Spotify later this month. Just don’t look for Sage Against the Machine at traditional rager venues. The band is most likely to perform at nurseries and family-friendly plant festivals, such as their upcoming gigs on April 13 at the Puente Latino Assn. Earth Day celebration at DeForest Park in Long Beach, April 21 at the Earth Day Celebration, plant swap and market in Thousand Oaks and May 25 at the Museum of Art and History in Lancaster. (Check out their Instagram page @nativesageagainstthemachine for exact times.)

Nicole Calhoun, left, Evan Meyer, Hector Cervantes, Jason Suddith and Antonio Sanchez are five of the six native-plant nerds who make up the L.A. punk-rock band Sage Against the Machine.

(Rio Asch Phoenix)

People who attend the band’s performances get to hear lyrics that are often playful, as in the bouncy polka “Munching Milkweed,” about a monarch’s metamorphosis from caterpillar to butterfly, and sometimes playfully suggestive, as in “California Poppy Chulo,” a play on the Spanish phrase “papi chulo,” which translates to “a hot guy.” Ostensibly, it’s a song about bees looking for flowers to pollinate, but the opening lines make it clear that this is more than a nature documentary:

He’s a California poppy chulo,

Every pollinator that you know

wants to get a little piece of that c—

“The c—” is a vulgar Spanish word for buttocks commonly used in popular reggaeton music. “But it would never appear in print in La Opinión [L.A.’s Spanish-language newspaper],” Sanchez said laughing. “But you know, those guys are having sex with plants; you almost want to put a partition up because the bees are enjoying it so much. It’s like, ‘You’ve got to calm down! Do you not know I’m looking at you right now?’”

Frontman Antonio Sanchez on his knees with Jason Suddith keeping up behind him on rhythm guitar.

(Rio Asch Phoenix)

The lyrics, mostly written by Sanchez, can be biting at times, as in “PSA,” a hard-driving song about white sage poaching. They also can be poignant, like in the song “I Wanna Be a Native Plant.” In a video posted on YouTube, Sanchez roams the stage, jumping, crouching, rubbing his head and shout-crooning, “I wanna be a native plant, I wanna grow where they say I can’t. … Mama, make me a native plant, so I can grow where they say you can’t.”

More often than not, Sage Against the Machine’s songs are funny, even when they have an edge. The band’s most popular song, “Baby I’m a Botanist,” has about 18 versions, Sanchez said, because he’s always improvising new lines while the basic premise stays the same: A plant lover falls in love with a botanist.

“It’s funny because so many people think that song is about them,” Sanchez said, “but really it’s just me, who doesn’t have a degree and barely even went to school for plants, saying, ‘You don’t have to have a degree to be a botanist.’ Some of our greatest plant people have hands too hard to shake because they got [them] working with plants. But the native-plant world can be super stuffy — ‘Oh, you’re not pronouncing Salvia apiana correctly’ — and we’re just trying to break down some of those barriers and have fun with plants.”

Nicole Calhoun, bass player for the band Sage Against the Machine.

(Rio Asch Phoenix)

Their catalog has tender songs too, including the romantic ballad co-written by Meyer and Sanchez, “Your Love is Like a Manzanita, Slow to Grow, Quick to Die,” instantly understandable to anyone who has ever been in love or tried to grow a finicky manzanita. They already have one live album on Spotify, and plan to drop another this month.

They’re such a unit when they perform — professional, focused yet still having fun — that it raises the question: Will Sage Against the Machine ever hit the big time? It’s something they all say they would love, “if my boss would give me a year and half off to tour,” Ramirez said jokingly, but the bandmates aren’t holding their breath. Major success is probably unlikely, Cervantes said, because their songs are too specific to California and its plants. “If it goes that way, then it’s meant to be,” Cervantes said, “but we’ve built a little niche for ourselves that’s pretty much our own.”

Then again, who knows. If the Beach Boys could make surfing a national phenomenon, who says Sage Against the Machine can’t get everyone excited about California buckwheat and white sage? It’s like what Sanchez screams in his favorite song, “Connected:”

If you are the lightning, then I’ll be your fire and she’ll be the wind; what does that make us?

If you are the clouds; then I’ll be your rain and she’ll be the earth; and what does that make us?

Connected! Connected! Connected!

We are all connected!

Lifestyle

Can Netflix build a factory for appointment TV?

Jon Stewart and John Mulaney.

Ryan West/Netflix

hide caption

toggle caption

Ryan West/Netflix

Jon Stewart and John Mulaney.

Ryan West/Netflix

A week’s work of live programming on Netflix wraps up this evening with the final episode of comic John Mulaney’s twisted talk show re-invention, Everybody’s in L.A.

So it’s worth a moment to consider the double-edged results in the streamer’s attempt to create an avalanche of appointment television in just seven days.

On one hand, you’ve got the juggernauts of Katt Williams’ Woke Foke live standup comedy special last Saturday, plus the roast last Sunday of champion quarterback Tom Brady – humbly billed as the Greatest Roast of All Time.

Both specials dominated Netflix’s viewership charts this week, as Williams’ viral trash talking and a procession of boldfaced names cracking tasteless jokes on Brady’s wealth, good looks and failed marriages kept the country buzzing. (See below how Nikki Glaser stole the show with her barbed cracks on host Kevin Hart.)

YouTube

And then there’s John Mulaney.

Building an anti-talk show

In truth, my heart is completely with Mulaney’s defiantly oddball project, which turns its back on many of the reasons you would do a show like this live in the first place. He kicks off every episode reminding viewers it is live with no delay, citing the time and temperature.

But he doesn’t really provide much of a reason why he’s delivering that information and he doesn’t reference the day’s news or current events – stuff which can distinguish a live TV event. He takes calls with questions from viewers – which makes sense for a live show – but often ends the conversation by asking what car they drive. When they answer, he hangs up; no punchline or indication why he asked the question.

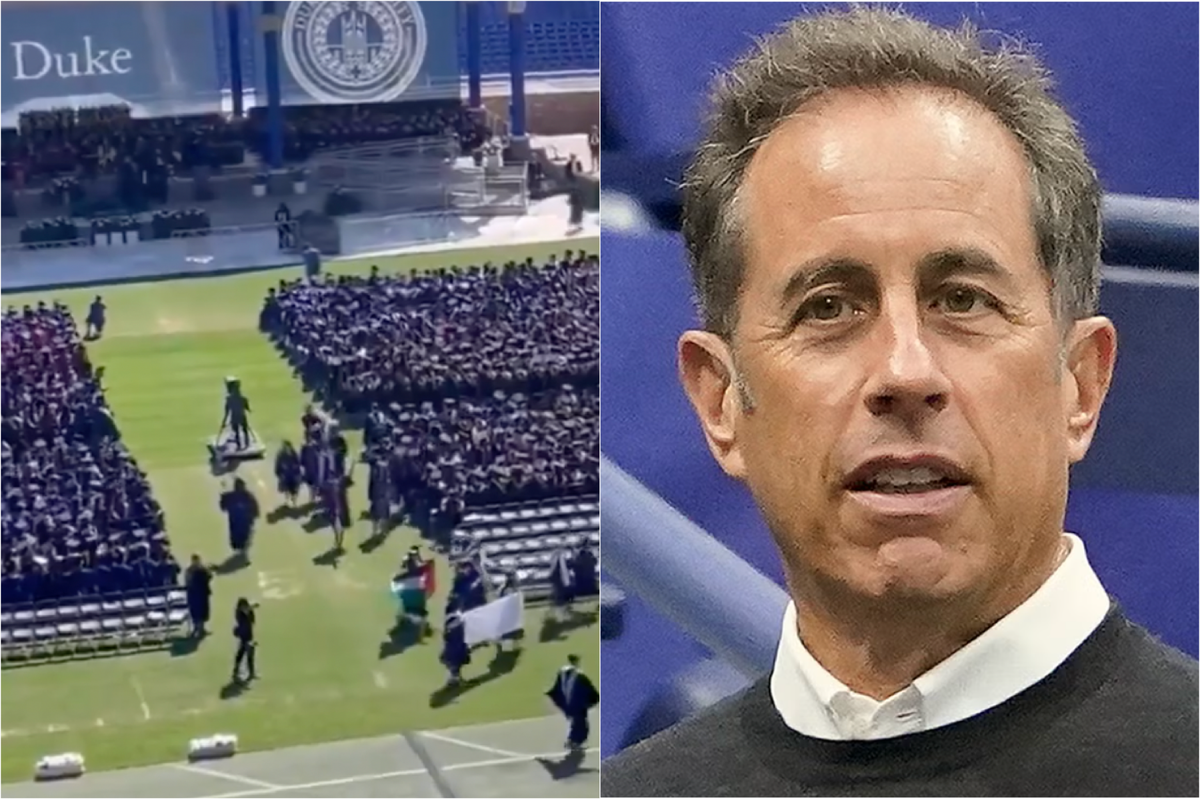

Everybody’s in L.A. actually feels like Mulaney’s attempt at an anti-talk show, in the same way David Letterman and Conan O’Brien deconstructed and lampooned basic tenets of television. It is often a delicious dance between truly funny surprises and awkward moments, with experts on subjects like palm trees and the paranormal sitting alongside comics like Jerry Seinfeld, Jon Stewart and Sarah Silverman.

Announcer/sidekick Richard Kind and a food delivery robot named Saymo.

Ryan West/Netflix

hide caption

toggle caption

Ryan West/Netflix

Announcer/sidekick Richard Kind and a food delivery robot named Saymo.

Ryan West/Netflix

But Mulaney’s show has run out of gas over time, slowly becoming less entertaining each night. Mulaney has also discovered a painful truth about standup comics who become TV hosts; it’s tough to ask questions of guests while making them look entertaining.

A flex that hints at the future of live streaming

Mulaney’s fading experiment, along with the Brady roast and Williams special, are part of the Netflix is a Joke Festival, which features hundreds of comedy performances across Los Angeles – a gigantic flex aimed at showing how the streamer has become the go-to destination for veteran and emerging comics.

But these projects also felt like a test of Netflix’s ability to offer live programming without glitches, which would also rack up lots of viewing time.

It’s obvious that there are two types of TV programming where streamers are still struggling to match the success of traditional platforms like broadcast networks and cable channels: live spectacles, including sporting events, and topical news and talk shows. So it means something to see streaming’s most successful service try to present several days of live programming with a similar energy.

Netflix probably sees this week as a roaring success. People are still talking about the Brady roast in other corners of media, as participants pop up on assorted TV shows and podcasts. And they have more live content coming, including a boxing match in July between 27-year-old Jake Paul and 57-year-old former heavyweight champ Mike Tyson, and WWE professional wrestling shows next year.

There’s even rumblings that Netflix may work out a way to get an NFL pro football game or two.

Indeed, even as Netflix has pioneered the idea of binge watching TV on the viewer’s schedule, it’s also plain that fans want appointment television. These are shows so special, you have to watch them as they are happening – either because you can’t wait, or to avoid spoilers, or to have a communal experience.

The Williams, Brady and Mulaney shows prove Netflix can offer more of these moments. Charting what form that takes — and how their competitors react – will probably be one of the most important media stories of the next year.

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoBrussels, my love? Champage cracked open to celebrate the Big Bang

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoAustralian lawmakers send letter urging Biden to drop case against Julian Assange on World Press Freedom Day

-

Education1 week ago

Education1 week agoHow Counterprotesters at U.C.L.A. Provoked Violence, Unchecked for Hours

-

News1 week ago

A group of Republicans has united to defend the legitimacy of US elections and those who run them

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoHouse Dems seeking re-election seemingly reverse course, call on Biden to 'bring order to the southern border'

-

World1 week ago

World1 week ago‘It’s going to be worse’: Brazil braces for more pain amid record flooding

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week ago'Stop the invasion': Migrant flights in battleground state ignite bipartisan backlash from lawmakers

-

Politics1 week ago

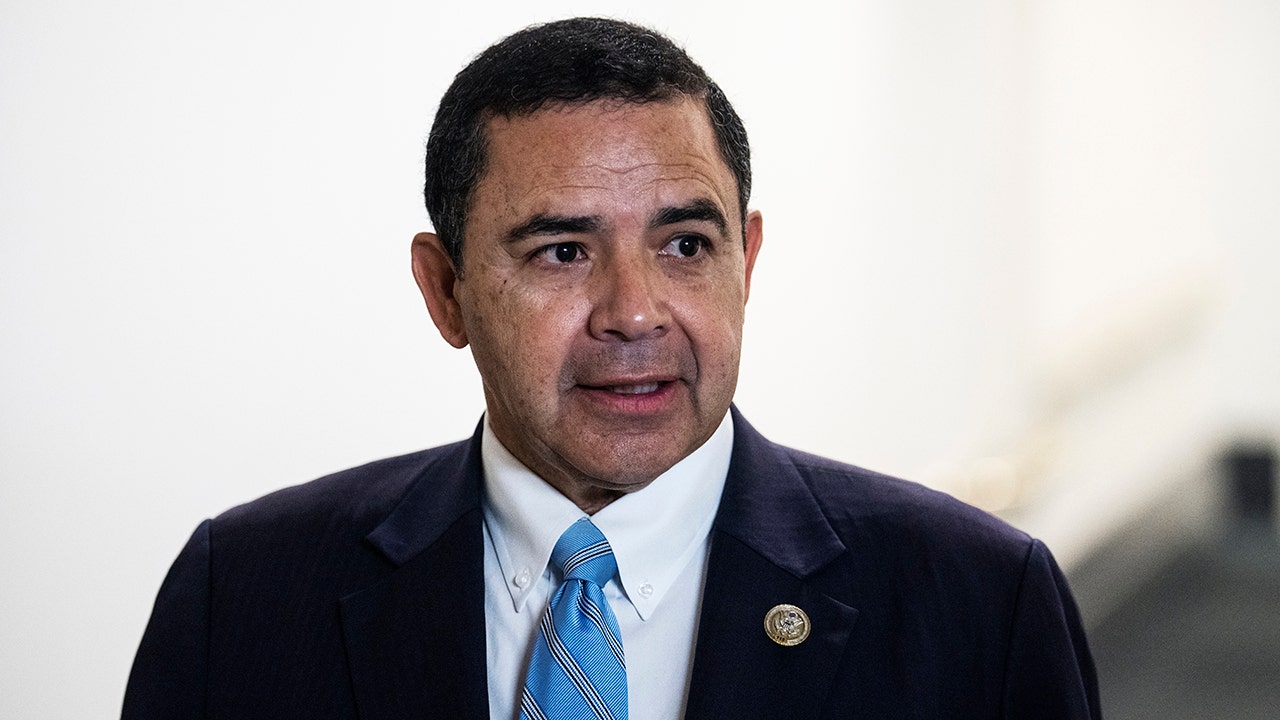

Politics1 week agoDemocratic Texas Rep. Henry Cuellar indicted by DOJ on conspiracy and bribery charges