Entertainment

The problematic white, male Southern writer who inspired a diverse generation

“My uncle gave me a replica of ‘A Feast of Snakes’ in alternate for cleansing out his shed,” says S.A. Cosby, writer of “Razorblade Tears,” remembering his first encounter with the late Southern writer Harry Crews. The Tennessee author Kevin Wilson occurred upon Crews’ paperbacks whereas studying between lessons in a Vanderbilt College English division workplace. The novelist Ryan Chapman picked up Crews when his now-wife declared “A Feast of Snakes” her favourite novel. Solely later did she reassure him she didn’t share the cult writer’s nihilistic tackle real love.

Critics and awards anoint some authors as legends. Others rely on word-of-mouth and prose that stands the take a look at of time. “Artwork’s major goal was to supply up pleasure and crush the human coronary heart with a residing reminiscence,” Byron Crews writes, of his father’s central focus, in an electronic mail. “Papa usually judged writing by the diploma to which it’s sincere and resonates and is memorable — throughout time — throughout years.”

This week, Penguin Classics will reissue Crews’ memoir “A Childhood: A Biography of a Place” (1978) and his debut novel, “The Gospel Singer” (1968). The imprint’s writer and buying editor, Elda Rotor, recalled being “intrigued by his affect as an writer and a instructor and curious in regards to the craft of storytelling.” Struck by Crews’ “bigger than life” mark on literature, she hopes the reissues will permit a brand new, wider readership to wrestle along with his works and “revisit them via the lens of classics.”

Crews was a totally Southern novelist, however there’s nothing folksy, by no means thoughts pastoral or genteel, about his writing.

(Property of Harry Crews)

For a number of years now, Penguin Classics has taken nice pains to republish unsung works by marginalized authors. So what prompted them to revisit a straight, white male whose work is fraught with racism and a masculinity so poisonous it someday shoots previous misogyny and straight into assault? The reply is as difficult as the person himself.

At instances higher often called a tattooed provocateur who sported a mohawk lengthy into his later years, Crews was the unusual and blistering writer of 20-odd works. Between his start right into a Georgia sharecropping household in 1935 and his 2012 dying in Florida as a retired professor and former Marine, he witnessed the South’s shift from a rural society to an more and more industrial and cosmopolitan area marked by the civil rights motion and its backlash.

The conception of the standard Southern author has developed simply as dramatically over these many years. The one fixed throughout generations has been the paradoxical place of Southern lit: acknowledged as maybe essentially the most vibrant regional writing within the nation but usually dismissed as too idiosyncratic to characterize American literature at giant. Its bestsellers, from “The place the Crawdads Sing” to John Grisham’s thrillers, are hardly ever related to it; “Gone With the Wind” certainly is, however it rang false when it was new.

Canonical midcentury Southern writers — Faulkner, O’Connor, Welty — had been usually perceived as white eccentric outsiders. In the present day the sector displays the variety and modernity of the area (Jesmyn Ward, Tayari Jones, Kiese Laymon, Cosby and plenty of others). They characterize the entire of America — however then, so did their forbears, as a result of, as Imani Perry just lately argued, the South is America. It’s a farce to isolate racism, classism and misogyny previous or current in a single area.

Amongst these combating again towards such handy parlor tales was Crews, whose work serves as a bridge between Southern writers previous and current. Richard Howorth, the proprietor of storied Sq. Books in Oxford, Miss., notes that whereas Crews’ voice was “distinctly Southern,” he was additionally “unquestionably unaffected, real. There was nobody like him on the time.”

Harry Crews in his later years. Penguin is reissuing his memoir, “A Childhood,” and his novel “The Gospel Singer.”

(Property of Harry Crews)

There’s nothing folksy, by no means thoughts pastoral or genteel, about Crews. With caustic and fabulist writing, he exhumed the ghosts of America’s unique sin.

Crews’ memoir is studded with stunning occasions: After dropping his father at age 2, he was raised as his uncle’s baby till that uncle practically murdered Crews’ mom; he survived untreated polio and an unintended toss right into a vat of boiling water with a hog; he closes the guide with an evangelical revival that evokes the disturbing sexual assault of one other baby.

That is an account of a life devoid of choices or guideposts save for ritual and religion. His novels too are set in a lawless South, their characters so surreal and disturbed they could possibly be discovered solely in dead-end cities marked by filth roads and moonshine. In “The Gospel Singer,” the title character returns to carry out in his hometown simply as his outdated acquaintance, the Black preacher Willalee, who shares a reputation with Crews’ childhood buddy, is charged with the rape and homicide of the singer’s childhood sweetheart. The singer is trailed, in the meantime, by a freak present the likes of which Katherine Dunn couldn’t have imagined.

Wilson, a professor at Sewanee, wrote the introduction for “The Gospel Singer.” The novel is “horrific,” he notes in an interview — and but “the sentences at instances are simply unbelievably stunning.” Constructing on this distinction, Wilson debunks any rumor of sentimentality within the work: “Crews doesn’t have nuance relating to race or gender or faith or actually something, however the one place he’s nuanced is his language.” By being “wildly exact and violent,” Crews’ type captures a society unsuccessfully struggling to maneuver previous its complicity within the horrors of slavery.

“You’re implicated each minute of your life right here, proper?” Wilson provides. “Like, if it is a damaged place that’s haunted by the specter of all this violence and cruelty, then merely current in it makes you culpable.” Even the stunning conclusion of “The Gospel Singer” leaves Wilson with the impression that “Crews isn’t essentially making a commentary on race. To him, there’s simply no escaping the cruelty and violence of this world.”

Cosby, a local and lifelong resident of Virginia, additionally expanded in an interview on his relationship to Crews’ work. “I grew up in a small city the place there’s a large Accomplice statue in entrance of the courthouse that sends a message to you as a Black individual,” he says. “Don’t search for redress of grievances. I all the time love studying his stuff, as a result of, even when [Crews’] characters will embrace the Confederacy or the Misplaced Trigger, he doesn’t embrace it. He ridicules it.”

For Crews, it’s in the end certain up in school: Stoking racism distracts poor white folks from organizing towards the elites. His bleak observations keep away from judgment, but the carnage in his writing speaks for itself. And not using a ethical reckoning, there isn’t sufficient cash, medicine or faith to avoid wasting a group from itself.

“Papa usually judged writing by the diploma to which it’s sincere and resonates and is memorable,” Byron Crews (proper) says of his father, Harry.

(Property of Harry Crews)

Cosby and Wilson spoke at size about how Crews exceeds even Faulkner and O’Connor in depicting a grotesque anti-pastoral that spares nobody. “After I learn him,” says Cosby, “I all the time felt like he was an individual who realized racism, sexism, misogyny had been all incorrect, however as a substitute of shying away from [these horrors],” Crews opts for “sensory overload.” He imagines Crews saying, “I’m not going to provide you any ethical proclamations. However I’m going to point out you ways dangerous it might get.”

Finally, the feelings and conflicts Crews depicted weren’t certain by geography. He wrote about nothing lower than the starkest extremes of human nature.

In “A Childhood,” he asks who would inform his son about him. He surmises, “Just a few motorbike riders, bartenders, editors, half-mad karateka, drunks, and writers. They’re scattered everywhere in the nation, however even when he may discover them, they might converse to him with no shared voice. … For half my life I’ve been within the college, however by no means of it. By no means of wherever actually. Besides the place I left, and that of necessity solely in reminiscence.” He concludes the thought by explaining why he turned to memoir. “Solely using I, pretty and terrifying phrase, would get me to the place the place I have to go.”

Self-deprecation apart, Crews captured the uncooked essence of humanity in each fiction and nonfiction. Facet by aspect, these reissues type the whole image of an imperfect man who charged onerous into extremes to flee his cultural inheritance. Leaving the South was no reply; his demons belong to all of us. His journey was a nightmare we should all face earlier than waking.

LeBlanc is a guide columnist for the Observer. She lives in Chapel Hill, N.C.

Movie Reviews

Film Review: Secret: A Hidden Score (2024) by Hayato Kawai

“I just wanted to be an ordinary girl”

The rather successful debut of Taiwanese musician Jay Chou in 2007, “Secret”, sent ripples to the film industry of the whole of Asia, with a Korean remake coming up in 2021, and this year, a Japanese one titled “Secret: A Hidden Score”. This review will deal with the latter.

Minato was studying music in the US, but he came back to Japan after experiencing trauma and is currently studying piano at a prestigious music academy. One day, he hears a beautiful song played on the piano and becomes fascinated by the music. The song leads him to meet Yukino, who is the source of the music. Minato falls head over hills for the beautiful, cheerful, intriguing but also secretive and mysterious girl, and the two soon start hanging out as much as they can. Or better, as much as Yukino will allow, to the disgruntlement of another girl, Hikari, who also has feelings for Minato. Yukino helps Minato regain his will to be a musician, but one day, she suddenly disappears.

There is a pattern to the Japanese films we usually catch in European/Western film festivals, which makes “Secret: A Hidden Score” a kind of a novelty, since this is the type of film that is quite popular in Japan, but does not get out of the borders so frequently. Whether this is a good thing, however, is a whole other topic.

Hayato Kawai comes up with a very sensitive film about life in college, romance, and the concept of trauma and how people can heal. What is the most intriguing aspect of the whole narrative, however, is the relationship in the center of the movie, and particularly its imbalance. Minato falls for Yukino immediately, and while she also obviously likes him, she is holding back due to her secrets, in an aspect that makes the relationship, and subsequently, the whole film quite intriguing.

At the same time, this aspect, and again the whole movie, benefits the most by the charisma, the performance and the chemistry of the two main actors. Kotone Furukawa as Yukino in particular is a joy to watch throughout the movie, with the way her teasing and secretive nature eventually changes to a more open up one, and the way her whole story leads to drama being probably the best aspect of the whole film. Taiga Kyomoto as the nerdy, traumatized, hopelessly in love Minato is also quite good, with the interactions of the two being quite pleasant to watch. Gorgeous Mayuu Yokota as Hikari cements the prowess in the acting, while Ryota Miura and Ryotaro Sakaguchi as Minato and Hikari’s friends provide a very appealing humoristic element to the movie, even if they are too loud on occasion.

Furthermore, the twist is also good, even if not that surprising, with the last part that explains more about what happened being particularly well directed. That it explains more of the character’s actions and demeanor while creating additional empathy for them works quite well for the movie too. In that regard, the placement of the flashbacks, the revelations and the aftermath are well embedded in the story, in a trait that should also be attributed to the editing, which is definitely on a high level here.

At the same time, a number of issues all Japanese films seem to face nowadays are found in “Secret: A Hidden Score” also. The intense lagging, particularly in the last part of the movie, the scenes that seem almost unnecessary and an effort at forced sentimentalism are all here in abundance, bringing the quality of the whole thing several levels down. The extensive use of music is also an issue, although this is justified due to the nature of the story. Lastly, the story, and particularly the twist have not aged well since the original, with the whole thing appearing preterit on occasion.

In the end, “Secret: A Hidden Score” is a mixed bag of a film that draws the viewer in with the charisma and beauty of its protagonists and a story that seems intriguing in the beginning, only to disappoint in the end. Probably fans of romantic TV dramas will be the ones that will enjoy the film.

Entertainment

Review: Queer Black women shine at timely museum shows by Mickalene Thomas and Simone Leigh

Last week two solo exhibitions bearing voluminous — and timely — insight arrived at Los Angeles museums. Each is a mid-career survey of feminist painting, sculpture and video from the past 20 years, representing two very different artists for whom women’s place in the world is key.

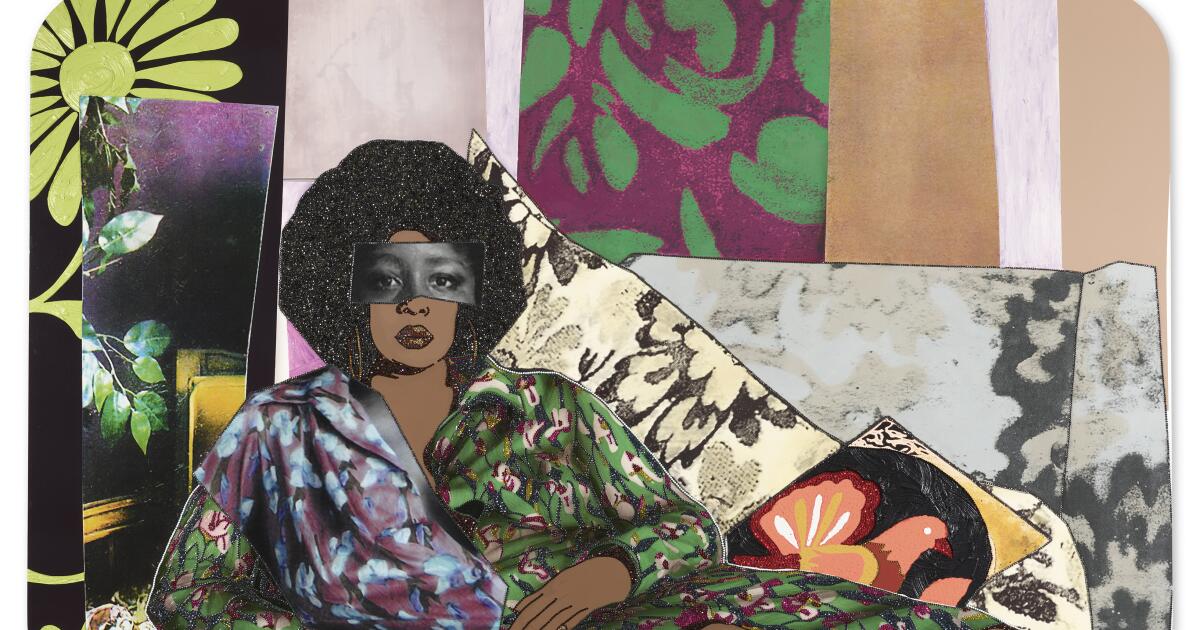

“Mickalene Thomas: All About Love” is a vibrant show of more than 80 paintings, drawings and mixed-media installations downtown at the Broad. Her work builds on a simple but trenchant observation: In the long history of Western painting, monumental portraits of Black women are almost nonexistent. Most of Thomas’ paintings pile on vivid color, brash patterning and lots of sparkling rhinestones, taking an exultant step toward rectifying the omission.

“Simone Leigh,” which is divided between the California African American Museum in Exposition Park and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in Mid-Wilshire, features 27 sculptures and three projections. Sober history is essential to Leigh’s often elegant work, which gives equal weight to the two adjectives joined in the term “African American.” Women’s images are abundant, and multiple artistic traditions gracefully entwine.

The fact that both artists are Black adds to the timely relevance. During the Jan. 6 domestic terrorist attack on Capitol Hill, a few Black faces were glimpsed amid the scandalously waved Confederate, Gadsden and “Appeal to Heaven” flags, but it is worth emphasizing that the number of those faces that belonged to women was roughly zero. Today, in a nation exhausted by dealing with the tenacity of systemic racism and riven with conflicts over straight white Christian male supremacy, Black women sometimes seem to be the linchpin barely holding things together.

Journalist Marianne Schnall, founder of the influential website feminist.com, once aptly noted that “Black women are by no means a monolith, and yet as a group have a deep understanding of the relational nature of freedom, precisely because they sit at various intersections of targeted oppression.” Add queer identity to the mix, and the comprehension deepens further.

Simone Leigh, “Cupboard,” 2022; stoneware, raffia and steel armature

(Christopher Knight/Los Angeles Times)

Thomas’ show was co-organized by Broad curator Ed Schad and Rachel Thomas of London’s Hayward Gallery, where it travels next year. (Stops are also planned for the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia and Les Abattoirs in Toulouse, France.) The Los Angeles debut opens with an elaborate stage set that replicates façades of tidy row houses in Camden, N.J., just across the river from Philly, where the artist was born in 1971. More than a mere conceit, the theatrical façades establish domestic settings as integral to Thomas’ aesthetic. On doorsteps, welcome mats are laid out.

Living rooms, rec rooms and finished basements turn up as installation formats throughout the show, while the compositions in her monumental portraits tightly collage figure and ground. The self-portrait in “Afro Goddess Looking Forward” is typical: Black-and-white photographs of Thomas’ eyes, some tabletop greenery and a portion of her torso mix with abundant painted features. The entirety of the figure is part of a dynamic patchwork that incorporates furniture, pillows, wallpaper and other accoutrements of a homey interior. Thomas presents as a Gen X Matisse.

Visually, there’s no separating the artist from her domestic environment, even in the imagination, so dazzlingly exuberant are the two fabrications. The strategy is repeatedly employed in paintings of friends, lovers and family, where figures merge with ground. The union comes across not as a limiting confinement but as a refuge — a contained space of at times boisterous play in which creative exploration unfolds.

Queer artists often regard the private home as a safe place for resourceful invention, given a public realm that puts forward scant models for living a life, not to mention offering abundant danger for doing so. Thomas is no exception. In one room lined with faux-wood paneling and cherry-red ottomans, she even shows herself in each painting twice, dressed in form-fitting animal-print tights and happily engaged in wrestling matches with herself. In another, an elaborate video montage of the brilliant and outspoken singer Eartha Kitt can be viewed from comfortably upholstered furniture in a convivial living room.

Then there’s her trademark use of craft-store rhinestones, which is multipurpose. Hair, body contours and facial features are often lined with the glittery paste, sometimes multicolored. The pictures’ flatly painted skin and two-dimensional patterning in textiles and wallpaper are set into shimmering visual motion. The paintings become performers, like entertainers on TV or the stage.

Forget Hobby Lobby. This sparkly craft-store aesthetic perform a vernacular consecration of the women she paints (and she paints only women). Rather than tacky, the rhinestones are beguiling. They make you smile.

Mickalene Thomas embeds her portraits of Black women in decoarative interiors

(Christopher Knight/Los Angeles Times)

Elsewhere, Thomas incorporates queer predecessors in paintings of abstract heads. A borrowed Andy Warhol “Flower” becomes an eyepatch, while topsy-turvy eyeballs, pushed to the margins of a face, recall Jasper Johns’ borrowing of similar elements from Picasso’s “Woman in a Straw Hat.” Thomas is identifying family.

Sometimes the pictorial setting is layered into the exhibition’s physical installation. One gallery filled with potted plastic plants features collage-style paintings of pin-up nudes from Jet magazine. Thomas has installed several of them on a wall dominated by a photo-enlargement of a pointedly empty closet. Jet cheesecake photos were surely made with male subscribers in mind, but she identifies lesbian desire as a vital element within the magazine’s audience. Black diversity is real.

Over at CAAM and LACMA, “Simone Leigh” is a traveling exhibition organized by the Institute of Contemporary Art / Boston, where it was seen last year. Included are several sculptures shown in the American Pavilion at the 2022 Venice Biennale, where Leigh, now 56, represented the United States. As at the Broad, male figures are nowhere to be seen.

Leigh has said that her work represents a “creolization” of art, mixing prominent European and Black traditions. Some of what is implied by the term is evident in the remarkable “Martinique.”

Simone Leigh, “Martinique,” 2022; stoneware

(Christopher Knight/Los Angeles Times)

Five feet tall, the cobalt blue stoneware figure of a lifesize headless women in a voluminous, bell-shaped skirt shows her cupping aggressive, bullet-like breasts in her hands. Titled for the island of Martinique, a former French colony in the Caribbean that legend held was once occupied solely by women, Leigh’s 2022 sculpture derives from a mid-19th century monument in the capitol, toppled during Black Lives Matter protests two years earlier.

The destroyed monument was a marble figure by French Salon artist Gabriel Vital Dubray that celebrated Martinique native Joséphine Bonaparte, first wife of Emperor Napoleon, who was instrumental in reviving slavery on the island despite its abolition in France. Dubray’s mediocre statue had already been beheaded three decades ago — a symbolic decapitation that couldn’t help but recall Marie-Antoinette’s actual fate at the guillotine. The sculpture stood headless in a public park until July 2020.

Think of Leigh’s subsequent sculpture as a monument to its headless-ness — at once a mockery of Joséphine’s thoughtless ignorance and a captivating salutation to the actual power of symbolic resistance. The volumetric, jug-like form of “Martinique” emphasizes clay’s eternal role as a vessel, which the artist fills with new meanings by virtue of her chosen forms and referents.

Clay is the medium most often encountered in Leigh’s art, whether in glazed form or as the raw material for works then cast in bronze. Shiny stoneware sphinxes in modulated natural hues, an 11-foot mound of raffia crowned by the feminine symbol of a cowrie shell, a suspended cluster of several dozen breast-shaped terracotta gourds with golden nipples and pierced by metal antennas — sculpture’s most ancient substance is typically made sleek and modern in her hands.

Mickalene Thomas installed pin-up paintings on a photo blow-up of an empty closet

(Joshua White)

Much of the work is a hybrid of female and architectonic forms — literally, woman as shelter.

“Herm” remakes an ancient Greek boundary marker or signpost, historically composed of a squared stone pillar with a carved male head on top. Leigh’s version employs a cruciform bust of a woman instead. A simple vertical slit is in front where a Greek phallus would protrude, and a shapely striding leg extends from the rear, together feminizing the bronze. Her signpost sculpture stands more than eight feet tall. Amazonian in scale, it insists that a viewer look up to the boundary it marks.

A bronze “Sentinel,” its surface featuring a rich black patina, transforms a traditional sphinx motif. A horizontal, corrugated body (think of the shape as a sheltering Quonset hut or nourishing grain shed) is topped at one end by a female head, its Afro hairstyle smoothed into a turban form. Incongruously, this watchful guardian’s face has no eyes, a motif common to all but one sculpture in the exhibition. The internalized, inward-looking result merges with a blank screen, onto which viewers project their own perceptions. Leigh’s best work generates a sense of intimate connection, even when its size approaches monumental.

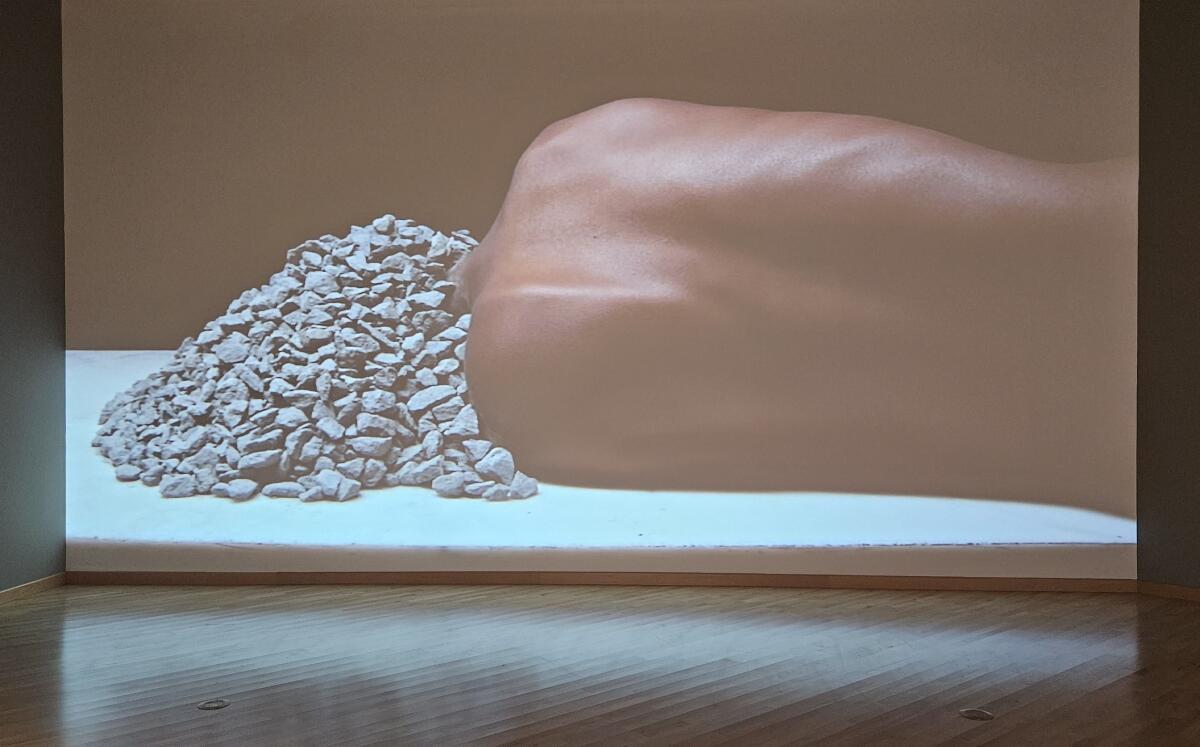

One moving work is a wall-size, single-channel video projection of a recumbent Black torso, seen from behind, the head obscured beneath a stony pile of gray rubble. Made in tandem with Brooklyn-based artist Chitra Ganesh — when they work together, the duo goes by the name Girl — it turns the European tradition of a reclining female nude inside-out, making the gender ambiguous and burying the figure’s gaze. (A wistful musical soundtrack, all wind instruments and drums, was composed by Kaoru Watanabe.) Look closely, and the mountainous image, seemingly static, is gently breathing. Whether the barely rising and falling ribcage represents restorative sleep or a dying breath is hard to say.

In both parts of the show, a bothersome hunt is required of visitors to find object labels too discreetly printed in black typeface against dark brown walls (a phone flashlight comes in handy). The only real downside, though, is the bifurcation between two venues located across town from each other. The split diminishes the retrospective punch.

The more satisfying presentation is at CAAM, where the 13 works span two decades, allowing for some sense of artistic evolution and reverberation. At LACMA, all but four of the 17 pieces date from just the past two years; the installation is lovely, but it’s more like a contemporary gallery show than a museum survey.

Simone Leigh, “Sentinel,” 2019; bronze

(Christopher Knight/Los Angeles Times)

The prominence of the exhibitions by Thomas and Leigh — highly accomplished, queer Black women — is crucial, however, especially as June’s Pride celebrations commence. At least 515 anti-LGBTQ bills, a record number, are pending in state legislatures across the country, representing an unspeakable mass of public hate. Misogyny, a core driver of homophobia, is deeply embedded in American life.

It has been since at least 1692. That was the year Bridget Bishop was ascertained to be a witch by frightened, conformist Puritan religious elders in the Province of Massachusetts Bay. Bishop, a thrice-married mother of four, was hauled away and lynched on Gallows Hill in Salem Village after a bizarre eight-day trial.

Three centuries later, as a criminally convicted former U.S. president bellows “witch hunt” into every available microphone, the madness endures, the cruelty continues. When Supreme Court Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr. and his cohort stripped women of bodily autonomy in overturning long-settled abortion rights two years ago, the conservative Catholic jurist resurrected the discredited opinions of British judge Matthew Hale for support. Hale, a Puritan sympathizer and later Lord Chief Justice of England, sent two women to their doom as “witches” after a trial in 1664.

Alito’s absurd citation of a notorious misogynist was widely greeted with a mix of disgust and ridicule, but not surprise. (Even though a nearly two-thirds majority of Americans say abortion should be legal in all or most cases, we live in a country where rule by a political minority is the norm.) Thomas and Leigh, judging from their generous and eloquent paintings, sculptures and videos, are unlikely to have been shocked. Saddened, for sure, and no doubt even scandalized — but not shocked.

More’s the pity. And more’s the reason for their bracing art.

Girl (Simone Leigh and Chitra Ganesh), “my dreams, my works, must wait till after hell. . . ,” 2011; single-channel video, color, sound, 7:14 min.

(Christopher Knight/Los Angeles Times)

Mickalene Thomas and Simone Leigh

Mickalene Thomas

Through Sept. 29 (closed Mondays) at the Broad, 221 S. Grand Ave., L.A. (213) 232-6200, www.thebroad.org

Simone Leigh

Through Jan. 20 (closed Mondays) at the California African American Museum, Exposition Park, 600 State Drive, L.A., (213) 744-7432, www.caamuseum.org; and also the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 5905 Wilshire Blvd., L.A., (323) 857-6000, www.lacma.org

Movie Reviews

Mr & Mrs Mahi Movie Review, Rajkummar Rao, Janhvi Kapoor

Movie Name : Mr & Mrs Mahi

Release Date : May 31, 2024

123telugu.com Rating : 2.25/5

Starring : Rajkummar Rao, Janhvi Kapoor, Rajesh Sharma, Kumud Mishra, Zarina Wahab, and others

Director: Sharan Sharma

Producers: Karan Zohar, Zee Studios, Hiroo Yash Johar, and Apoorva Mehta

Music Directors : Aadesh Shrivastava, Vishal Mishra, Tanishk Bagchi, Jaani, Achint–Yuva, Hunny–Bunny, Dhruv Dhalla and John Stewart Eduri

Cinematographer: Anay Goswamy

Editor: Nitin Baid

Related Links : Trailer

Rajkummar Rao and Janhvi Kapoor starrer Mr. & Mrs. Mahi finally released in theaters this Friday. Check out our review to find out more about the movie.

Story:

Mahendra Agarwal (Rajkummar Rao) dreams of joining the Indian cricket team but fails. His father pushes him to run the family business instead. Later, his parents arrange his marriage to Mahima (Janhvi Kapoor), a doctor. Mahendra is surprised to learn that Mahima loves cricket too. He hopes to achieve his dream with her support. Will Mahima support his wish and leave her job? How will their parents react? What will ultimately happen? Find it out in the movie.

Plus Points:

Rajkummar Rao once again proves why he is one of the finest actors around. His portrayal of a character experiencing hope, distress, failure, and ambition is truly remarkable.

Janhvi Kapoor looks decent on screen, and her dedication to learning cricket is evident in her performance.

Other actors, such as Kumud Mishra, who plays Mahendra’s father, and Rajesh Sharma as the coach, deliver commendable performances in their roles.

Minus Points:

While effective promotion is crucial for films like this, the trailer inadvertently revealed too much, robbing the big screen experience of its surprise factor. It’s like opening a gift only to find out you already know what’s inside.

The plot suffers from predictability, crying out for unexpected twists and turns to inject vitality into the storyline. Without these surprises, the viewing experience feels more like enduring a slow-paced match on a rainy day, testing the patience of even the most fervent cricket fans. Instead of delivering the adrenaline rush of a T20 match, the film unfolds at the leisurely pace of a test match, stretching the audience’s endurance to its limits.

The practice scenes and matches fail to ignite genuine excitement, blurring the lines between a cricket match and a family drama. This confusion persists throughout the unnecessarily protracted runtime, transforming the experience into a marathon rather than a sprint.

While the songs offer a brief reprieve, the lackluster background score fails to amplify the film’s emotional beats. Furthermore, the presence of numerous errors throughout the production only adds to the list of shortcomings.

Technical Aspects:

While the concept holds promise, its execution falls short. A tighter screenplay by Sharan Sharma could have redeemed the film, but missed opportunities abound.

John Stewart Eduri’s score misses the mark in elevating key moments, while Anay Goswamy’s cinematography fails to capture the dynamism required for a sports drama.

Nitin Baid’s editing feels sluggish, further hindering the film’s momentum. Nonetheless, the production values manage to scrape by with a passing grade.

Verdict:

On the whole, Mr. & Mrs. Mahi falls flat, neither delivering the excitement of a sports drama nor the warmth of a family tale. Instead, it stretches like an overlong short film, testing the patience of viewers. While Rajkummar Rao shines, the rest of the film feels like a tedious endurance test. Skip it and catch the upcoming T20 World Cup 2024 for real excitement.

123telugu.com Rating: 2.25/5

Reviewed by 123telugu Team

Articles that might interest you:

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoRead the I.C.J. Ruling on Israel’s Rafah Offensive

-

World1 week ago

World1 week ago€440k frozen in Italy over suspect scam by fake farmers

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoVideo: Protesters Take Over U.C.L.A. Building

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoHoping to pave pathway to peace, Norway to recognise Palestinian statehood

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoLegendary U.S. World War II submarine located 3,000 feet underwater off the Philippines

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoNYC Mayor Eric Adams announces Urban Rat Summit to combat rodent crisis: 'I hate rats'

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoAOC demands Senate Democrats investigate reports of Jan. 6 flags flown at Supreme Court Justice Alito's home

-

Science1 week ago

Science1 week agoSecond human case of bird flu detected in Michigan dairy worker