Entertainment

ShyBelligerent, reformed pimp turned rapper, shines a light on vulnerability in L.A. hip-hop

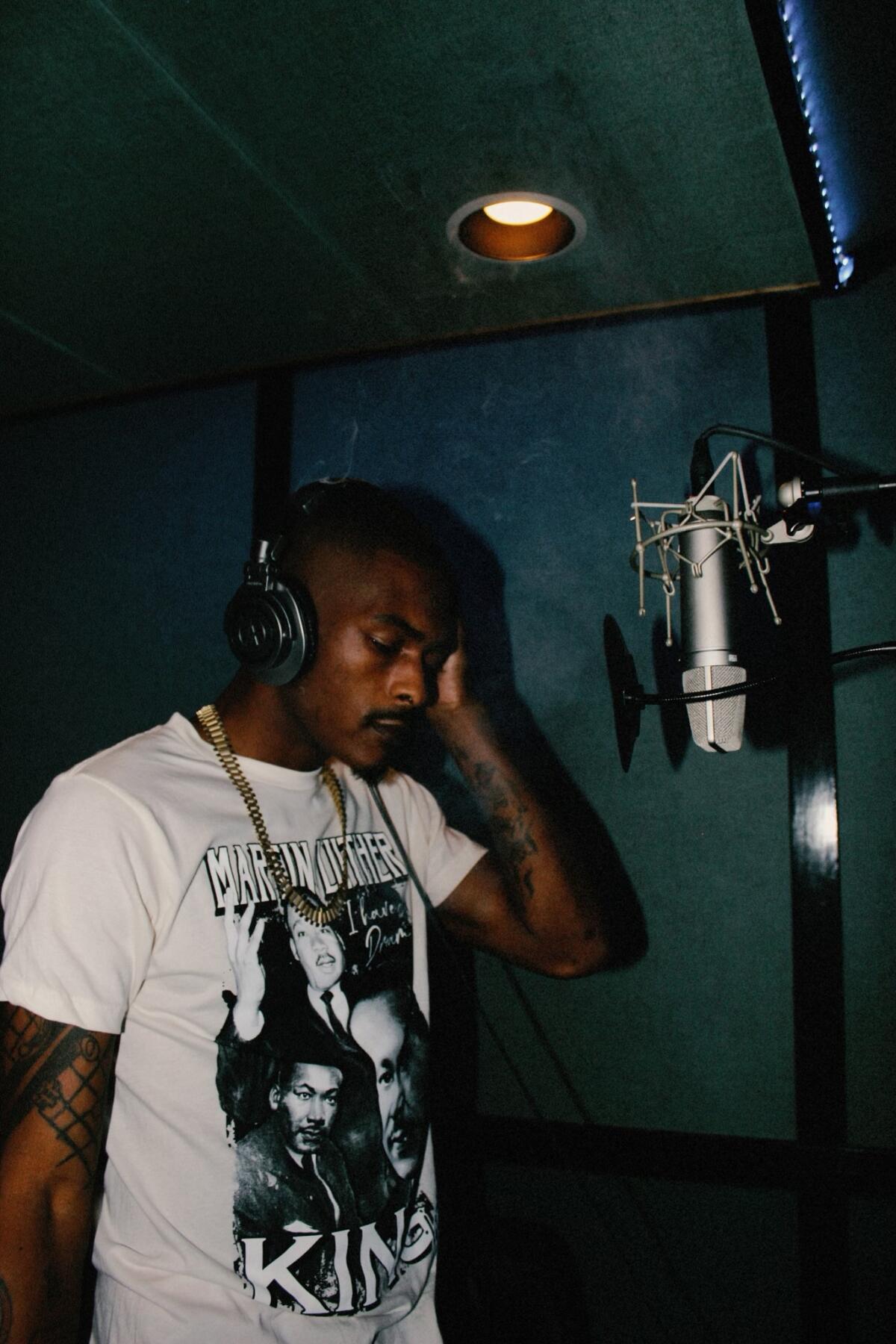

ShyBelligerent is hurting.

You can see it in his videos, where he paces helplessly through cemeteries and city streets and unfurnished bedrooms. You can hear and feel it in his voice. The 30-year-old rapper born Michael William, who is rail-thin with sharp, angular features and a pencil mustache, is also fearless on the page. He writes about all that’s been done to him, and all that he’s had to do.

“I can’t forget about the past,” he wails on his latest album, “It’s a Ugly Come Up.” “Where the Hennessey at? I’m finna down that. My whole life, I’ve been down bad.” The beats, mostly piano-based, are exquisitely complementary. Shy himself is movingly human — full of vim but also lonesome and afraid.

“I got to plot it out,” Shy says of the new album. “I actually got to make it a great project.” Much of his previous work was rushed and improvised. This time around, though, Shy took his sweet time. Lyrically and thematically, “It’s a Ugly Come Up” is focused without infringing too much on the spontaneity that has become Shy’s trademark.

For Shy, lyrics are of secondary importance. His power is in his voice — a twitchy, erratic, untethered yelp — that reveals him not as a victim, but as a vessel of chronic pain. The Compton native says he is tormented by what he’s experienced or, more to the point, what he can’t un-experience. How appropriate that Shy tweets under the handle “@sbbenthroughit.”

His song “Cry Me a River,” is a desperate airing of grievances. Thus far, “River” is the most viral song Shy has ever made (156,000 YouTube views and counting).

“In the L.A. music scene, my problem as a producer is that everybody sounds like everybody else,” says TooRawEntertainment, Shy’s producer who sends him beats from his studio in Arizona. “[Shy] definitely stands out. His delivery is crazy and his energy is even crazier. And he tells the truth, for real, in his raps.”

The “Cry Me a River” video captures the L.A. rapper flopping around in a raggedy tent adjoining a rail yard. Shy is not unhoused — he is in fact a very vocal tenant of the Housing Authority of the City of Los Angeles, better known as HACLA. Though he has a place to stay, at times he seems lost in his chaotic interior world. In conversation, the rapper lives up to the implied duality in his name — alternating between quiet and rambunctious. But if you only know him through his music, nothing can prepare you for just how demure and put-together he is in real life.

“I think it’s one of the most remarkable things about him,” says DeJon Paul, a rap critic and blogger from Inglewood who is also a regular on the popular hip-hop podcast “No Jumper.” His local gravitas provides a refreshing contrast to “No Jumper” host Adam22. Each year Paul rolls out the local equivalent of XXL magazine’s Freshman Class list. Shy was one of the chosen few in 2023.

In conversation, ShyBelligerent lives up to the implied duality in his name — alternating between quiet and rambunctious.

(David McGriff)

“He has this bombastic personality on wax and in his videos,” Paul said. “ But when you hang out with him or when you interview him, when you run into him in public, he’s quiet, stoic, he’s to himself, he’s reserved.” The explanation for that lies in Shy’s upbringing.

“It wasn’t your typical mother-father scenario,” Shy says. “My mother was supposed to fight for me, but she just wasn’t able to.” His mother walked out when he was an infant. His unstable father was not any better prepared for parenthood. As a child he was “signed over” to his stern, churchgoing grandmother and jazz-enthusing grandfather. Shy remained in their care until he was 15.

Some good came of this familial arrangement. His grandfather instilled in him a musical curiosity that persists to the present day (“That’s why my style is so unique”). But Shy was a cowed and glum child. His world, small to begin with, shrank by two when his parents left his life. He couldn’t make sense of it. The more he fumbled for answers, the more overwhelmed he became by entropy and uncertainty.

“Later down the line,” Shy says now, “I was able to speak up and ask questions and figure things out.” But in grieving his lost youth, he became quarrelsome and sometimes belligerent. Shy’s trajectory is all too familiar: frightened, neglected boys often become angry men.

For a time he sought release and restoration in the classroom (his favorite course was Honors English). The gridiron was another precious sanctuary; Shy played defensive end on the Compton High football team. Even then, however, he had designs on a rap career; it was around 2009 when he got serious about his craft. L.A. is a networker’s paradise and Shy likes to network, but he didn’t always. His teenage apprenticeship was completely informal and self-supervised.

“This was when YG was in his prime,” Shy says. At the time, YG was an up-and-coming wiry truth-teller, a fellow Compton rapper who turned into a superstar and provided Shy with a blueprint of how to succeed. “I was trying to make a name for myself then, but with the little resources I had, the little knowledge I had at that moment, it was rocky.”

William had at his disposal only the cheapest of equipment — RadioShack microphones and “busted-up laptops.” Eventually he built a functioning studio out of primitive equipment.

If Shy’s creative life suffered, it was because he had competing responsibilities. He fathered a child at 15. This enraged his fundamentalist grandparents, who sent him scrambling for steady work, much like Ice Cube on “A Bird in the Hand.” He worked in dollar stores, warehouses — any place that would pay him a legal wage. Shy’s employment history is largely aboveboard, but he’s done things for money that by his own admission are inexcusably vile.

As Shy’s rapping evolved, so too did his journalistic sense. He began to experiment with the vlogger model of YouTube street reporting. The following he gained from this activity wasn’t huge relative to the biggest vloggers, but it also wasn’t negligible. Shy says he has a knack for timing, for providentially capturing extraordinary scenes as they happen.

On tracks such as “Son of a Bitch,” William recounts a period in his life when he was “pimping hoes.” This isn’t a euphemism nor is it a case of hip-hop fabulism. He has direct experience trafficking women.

“It was for a short amount of time,” he says, while conceding that he was active long enough to inflict lasting damage on the women funneled into his “stable.”

“Having daughters would make you rethink the whole situation,” he says. “I’ve seen a bigger picture now.” These may sound like limp platitudes, but on “Son of a Bitch,” Shy sounds like the most spiritually tortured ex-trafficker in hip-hop history. (Suga Free with a conscience? All jokes aside, their rapping styles are very similar.)

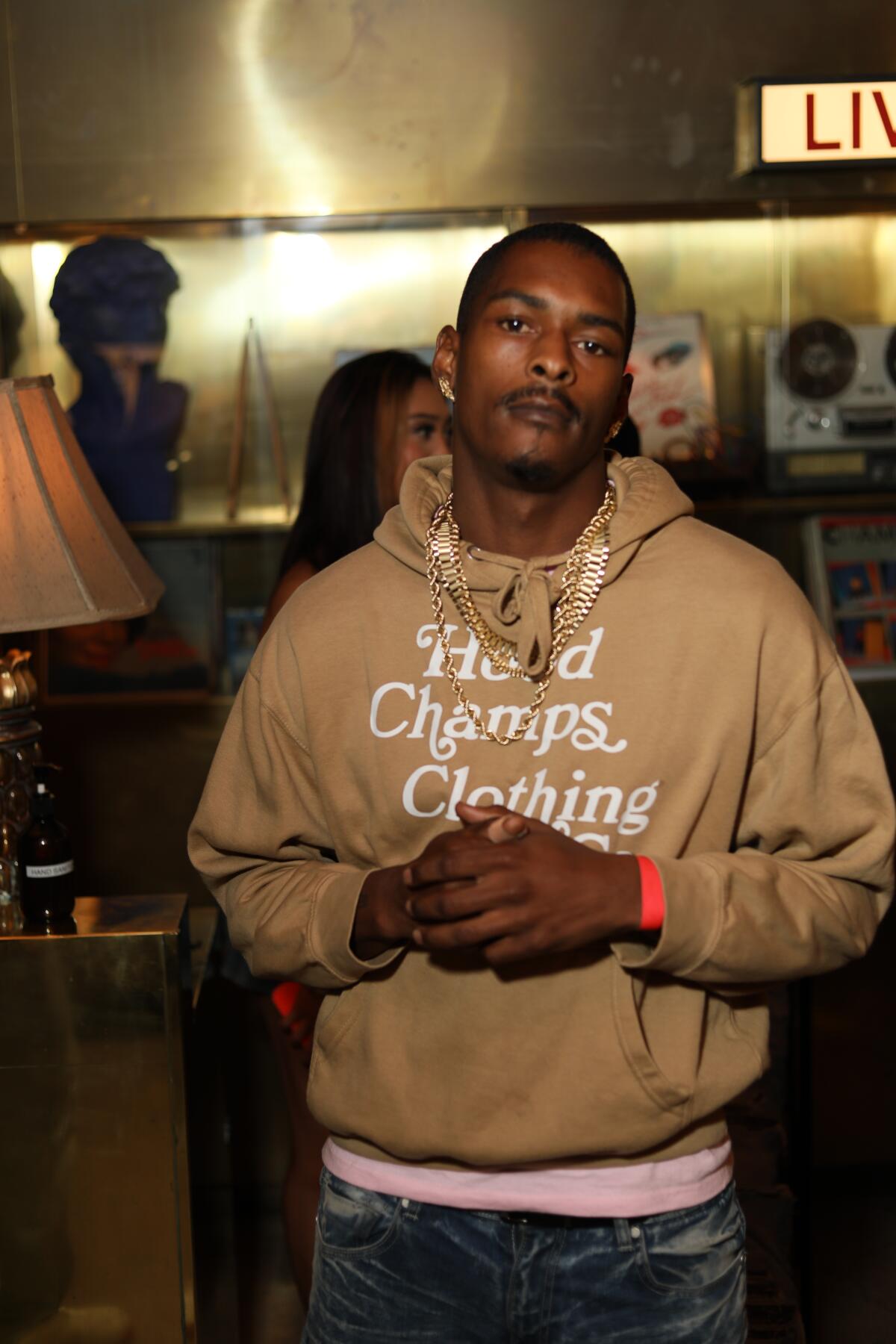

Watts had always functioned as a second home for Shy, and at some point he moved there permanently. In retrospect, Watts was the best place he could’ve gone. Shy’s identity is bound up, almost inextricably, with this close-knit community of 35,000. Would there be a ShyBelligerent if he still were mooning around Compton?

Watts functioned as a second home for ShyBelligerent and at some point he moved there permanently. His identity is bound up, almost inextricably, with the community.

(David McGriff)

Shy’s adopted home is fertile ground for rap talent. He currently lives in the low-slung, lemon-hued Nickerson Gardens apartment complex and identifies intensely with the place. In his X bio, Shy introduces himself as an unsigned artist from Nickerson Gardens. His free agency is a geographic catastrophe, and also an A&R failure, says Paul.

“I’m surprised TDE hasn’t snatched him up,” Paul says, referring to Top Dawg Entertainment, the prestigious label whose roster — Kendrick Lamar, Jay Rock, Schoolboy Q — descends on Nickerson every year for a Christmas jamboree and toy drive.

Therein lies a critical action verb: snatch. Shy is forever snatching defeat from the jaws of victory. He has talent, emotional courage, great sonic instincts (his beat selection is top-notch). But he often seems like an accident waiting to happen. “It’s a Ugly Come Up” is so feral, so brazenly uninhibited, that Schoolboy Q’s “Blue Lips” seems almost family-friendly by comparison.

Any major label would try to soften Shy’s rough edges — and who wants that? Certainly not him. For all the doubt and pain Shy has endured in his 30 years, for all the catastrophic blows to his psyche, he stands by his music. It’s his one source of self-esteem, self-efficacy and pride.

“I’m a musical genius,” he says flatly. Maybe that’s hyperbolic, maybe not, but his dramatic genius isn’t up for debate. In matters of using hip-hop to dramatize human hurt, there’s no question ShyBelligerent is as great as he says he is.

Movie Reviews

Movie Review: ‘Goat’ – Catholic Review

NEW YORK (OSV News) – “Goat” (Sony) is an animated underdog sports comedy populated by anthropomorphized animals. While mostly inoffensive, and thus suitable for a wide audience — including teens and older kids — the film is also easily forgotten.

The amiable proceedings center on teen goat Will Harris (voice of Caleb McLaughlin). As opening scenes show, it has been Will’s dream since childhood to play for his hometown team, the Vineland Thorns.

The inhabitants of Vineland and the other areas of the movie’s world, however, are divided into so-called bigs and smalls, with professional competition dominated, unsurprisingly, by the former. Though Will stoutly maintains that he’s a medium, those around him regard him as too slight and diminutive to go up against the towering bigs.

Despite this prejudice, a video showing Will more or less holding his own against a famous and arrogant big, Andalusian horse Mane Attraction (voice of Aaron Pierre), goes viral and inspires the Thorns’ devious owner, warthog Flo Everson (voiced by Jenifer Lewis), to give the lad a shot. Though Will is understandably thrilled, his path forward proves challenging.

Will has idolized the Thorns’ sole outstanding player, black panther Jett Fillmore (voice of Gabrielle Union), since he was a youngster. But Jett, it turns out, is not only frustrated by her situation as a star among misfits but scornful of Will’s ambitions and resolute in helping to deprive her new teammate of playing time.

Given such divisions, the Thorns’ fortunes seem destined to continue their long decline.

“Roarball,” the invented game featured in director Tyree Dillihay’s film, is essentially co-ed basketball by another name. As produced by, among others, NBA champion Stephen Curry, the movie — adapted from an idea in Chris Tougas’ book “Funky Dunks” — is an unabashed celebration of hoop culture both on and off the court.

Viewers’ enthusiasm may vary, accordingly, depending on the degree to which they’re invested in the real-life sport.

Moviegoers of every stripe will appreciate the fact that the script, penned by Aaron Buchsbaum and Teddy Riley, shows the negative effects of self-centeredness as well as the value of teamwork and fan support. Plot developments also showcase forgiveness and reconciliation.

Will’s story is, nonetheless, thoroughly formulaic and most of the screenplay’s jokes feel strained and laborious. Still, while hardly qualifying as the Greatest of All Time, “Goat” does provide passable entertainment with little besides a few potty gags to concern parents.

The film contains brief scatological humor and at least one vaguely crass term. The OSV News classification is A-II — adults and adolescents. The Motion Picture Association rating is PG — parental guidance suggested. Some material may not be suitable for children.

Read More Movie & TV Reviews

Copyright © 2026 OSV News

Entertainment

Philip Glass canceled a Kennedy Center show, but this conductor brings his work center stage at L.A. Opera

When Dalia Stasevska heard opera music for the first time, it was a moment of profound self-revelation. She was 13, growing up in the factory town of Tampere in the south of Finland, and her school librarian gave her a CD of Puccini’s “Madama Butterfly” along with a translation of its Italian libretto.

“As a teenage girl, this dramatic story touched my soul,” Stasevska says, adding that she still remembers the experience and thinking, “ ‘This music understands me, this is exactly how I feel.’ And that was…when I knew that I wanted to become a musician.”

Stasevska is now chief conductor of Finland’s Lahti Symphony Orchestra and a prodigious conductor of orchestral music in all forms. A busy guest baton with companies around the globe, she will make her L.A. Opera debut this Saturday with a production of “Akhnaten” by Philip Glass, running through late March.

John Holiday in the title role of L.A. Opera’s 2026 production of “Akhnaten.”

(Cory Weaver)

The seminal work by Glass lands at L.A. Opera just a month after the world-famous composer abruptly canceled June’s world premiere of Symphony No. 15 “Lincoln” at the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts. “While Philip Glass has pulled out of Kennedy Center, his music will be front and center at our production,” a rep for L.A. Opera wrote in an email.

Stasevska, with her razor-sharp appreciation of the power of Glass’ work, is the ideal conductor to bring it there.

Stasevska, 41, walks from the ornate foyer of the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, with its emerald green carpets and gleaming chandeliers, to the more ordinary hallways and cubicles of L.A. Opera’s offices. She’s been in town rehearsing for a few weeks and jokes with some of the show’s jugglers in a kitchenette, where she makes herself a machine pod coffee.

The conductor is petite with large, expressive eyes and a Cheshire cat’s smile. Her mouth often pulls to the right when she speaks, her admirable non-native English tugged easterly in a Finnish accent.

Opera remains her great love, and it seems a perfect twist of fate that Stasevska was tapped to conduct “Akhnaten.” She saw it for the first time in 2019 at a Helsinki cinema, in a global broadcast of a production by the Met. She couldn’t believe her friend dozed off.

“I was like, ‘How could you fall asleep? This was the best thing I’ve ever seen in my life. I would do anything to conduct this opera,’ ” she recalls saying.

Stasevska was born in 1984, the same year that Glass’ hypnotic, ritualistic opera, about an Egyptian pharaoh who dared to push monotheism onto his polytheistic culture, debuted in Stuttgart, Germany. Eight months later, Stasevska entered the world in the Soviet-controlled city of Kyiv, the child of a Ukrainian father and Finnish mother.

Conductor Dalia Stasevska, who is making her L.A. Opera debut with Philip Glass’ “Akhnaten,” says that opera is her first great love.

(David Butow / For the Times)

It was a fluke that she was born in Ukraine. Her parents, both painters, were living in the Estonian capital of Tallinn, also under Soviet rule, but found themselves in a Kyiv hospital close to family when Stasevska arrived. She’s never lived in Ukraine — she spent her first few years in Tallinn before moving to Finland at age 5— but her life has been infused with its heritage.

Her father, who as a teenager in Tallinn began to rebel against Sovietization, insisted on teaching Stasevska and her two younger brothers to speak Ukrainian at home. Her grandmother, Iryna, lived with the family and was an important caretaker for much of her childhood. Stasevska grew up hearing fantastic stories filled with dreamlike imagery of the homeland.

“She was such a civilized, cultural person,” Stasevska says of her grandmother, adding that she taught her grandkids everything she knew about her home country. That’s why, even though Stasevska was raised in Finland, she grew up eating Ukrainian food and hearing Ukrainian folk tunes. “I know the language and understand the culture,” she says.

Stasevska grew up poor, but music education was mandatory for her and her brothers: “My father said, ‘This is going to be your profession.’ It was no question that this is not a hobby. So we started practicing immediately, very determined. There was maybe some forcing involved,” she says, laughing.

She played the violin from age 8, but it was only after she heard Puccini at 13 that she fell in love with classical music. She became obsessed with the opera and orchestral repertoires and was immediately determined to play in an orchestra. She approached the headmaster at her conservatory who placed her in a string ensemble before advancing her to the symphony orchestra as a violinist.

At 18, Stasevska entered the Sibelius Academy in Helsinki, which is named after Finland’s most famous composer, Jean Sibelius. She couldn’t stop herself from stealing a peek at the school conductor’s score, copying bowings and poring over the details, but she didn’t indulge any dreams of taking the podium herself. “I was going every week to the concerts,” she says, “but it took me so long to see somebody that looked like me.”

She was 20 when she saw a female conductor for the first time, calling it “the second big moment in my life.” When Stasevska expressed interest in trying it herself, she was referred to Jorma Panula, a legendary conductor and teacher in Finland. Panula invited her to attend one of his masterclasses, and on the first downbeat of her first experience conducting, “I knew immediately that this was beyond anything I’ve experienced in my life,” she says. “It became this kind of madness moment.”

She loved the sheer physicality of it, she says, but also “that I can affect the music, and that I can affect the interpretation, because I had so much in my heart that I felt about the music.”

After completing her conducting studies in 2012, Stasevska assisted Panula — who emphasized discovering unique “gestures in such a way that the orchestral musicians know what you mean,” she says. She also worked with her fellow Finn, Esa-Pekka Salonen. Stasevska became principal guest conductor of the BBC Symphony Orchestra in 2019 and chief of the Lahti Symphony in 2020.

When she’s not globetrotting, Stasevska lives in Helsinki with her young daughter and her husband, Lauri Porra — a heavy metal bassist who is also the great-grandson of Sibelius.

She likes to champion new music — her 2024 album, “Dalia’s Mixtape,” featured works by Anna Meredith, Caroline Shaw and other contemporary composers. She is also a vocal supporter of the land where she was born and has spoken out against Russia’s war in Ukraine.

John Holiday as Akhnaten, with So Young Park, at right, as Queen Tye, in L.A. Opera’s 2026 production of “Akhnaten.”

(Cory Weaver)

Stasevska’s L.A. Opera debut arrives on the same week as the fourth anniversary of Russia’s invasion. Both of her brothers — one a film director, the other a journalist — moved to Ukraine and have borne witness to the war, which has given her “another level of experiencing this horror,” she says.

Stasevska has made it her mission to raise funds — more than 250,000 euros to date — to provide basic supplies particularly for children and elders who are without power and huddling in freezing cold homes. She has even driven in supplies herself by truck.

She has also conducted concerts there — and her next album will celebrate the country’s composers in a meaningful way. “Ukrainian Mixtape,” which she recorded with the BBC Symphony Orchestra in London, features works by five composers who range from the 19th century to the 1960s. Three are premiere recordings of artists who have been completely forgotten, which required a year of searching for materials.

“I think that it will not leave anybody cold,” Staveska says, “and I hope that it will inspire everybody to discover Ukrainian music more, and that we will hear it more on main stages of the world — where it deserves to be.”

For now, though, her focus is on ancient Egypt and Philip Glass — and opera. She says her goal, in every concert, is to give audiences the same experience she had when she was 13, that remarkable feeling that the music uniquely understands them.

Movie Reviews

Vishnu Vinyasam Movie Review – Gulte

2.5/5

01 Hrs 59 Mins | Romantic Comedy | 27-02-2026

Cast – Sree Vishnu, Nayana Sarika, Satya, Brahmaji, Praveen, Murali Sharma, Srikanth Iyyengar, Satyam Rajesh, Srinivasa Reddy, Goparaju Ramana and others

Director – Yadunaath Maruthi Rao

Producer – Sumanth Naidu G

Banner – Sree Subrahmanyeshwara Cinemas

Music – Radhan

Since 2023, with three commercial hits and one critically acclaimed film, Sree Vishnu has established himself as a minimum guarantee hero and built a loyal audience. To continue the success streak, he chose yet another romantic comedy film, directed by debutant Yadunaath Maruthi Rao. ‘Aay’ fame, Nayana Sarika, played the female lead role and Radhan, scored the music for the film. After creating enough curiosity among the audience with the teaser and trailer, the film was finally released in theatres today. Did Sree Vishnu, deliver yet another hit with a romantic comedy film? Did Nayan Sarika, score a hit in Telugu, after AAY & KA? How does the debutant director, Yadunaath Maruthi Rao, do? Did the music director, Radhan, come up with memorable songs and score? Let’s figure it out with a detailed analysis.

What is it about?

Vishnu(Sree Vishnu), works as a junior lecturer at a college, where Manisha(Nayan Sarika), works as the head of the department(HOD/faculty). Manisha, with her eccentric characteristics, intrigues Vishnu and both of them eventually fall in love with each other. When everything is going well for the couple to get married, Manisha informs Vishnu about a flaw in her Jathakam. What was the Dosham(flaw) in Manisha’s jathakam? How did it impact her prospects of getting married before meeting, Vishnu? Why did Vishnu initially get reluctant to marry Manisha, after hearing about her Jathaka Dosham? Will the couple sort out all the issues and get married eventually? Forms the rest of the story.

Performances:

Sree Vishnu, with his comedy timing generated a few fun moments that worked in favour of the film. However, in an attempt to appear effortless, he went overboard at times and appeared monotonous at a few places. Nayana Sarika got a good role and she delivered a good performance. She looked good throughout the film and appeared confident.

Satya, got a full-length role and he was able to generate a few laughs here and there with his comedy timing. Srikanth Iyyengar’s performance looked over the top and his portions looked rushed and very artificial. Srinivasa Reddy played a role similar to Mallikarjuna Rao’s role in Raviteja’s movie, Venky. He did an ok job but it seemed like he did dub for his role in the film? The film had Brahmaji, Praveen, Murali Sharma, Satyam Rajesh, Goparaju Ramana and a few others, in character roles. All of them made their presence felt but none of their roles gave the desired impact and extra mileage.

Technicalities:

Cinematography by Sai Sriram, is a major plus to the film. The visuals looked colourful, vibrant and gave a pleasant look to the film throughout. Radhan’s music should have been better. The songs scored by him were below par and the background score was pretty standard. Editing by Karthikeyan Rohini, was alright. He tried to cut the film with a very crisp runtime of around two hours and yet, ended up having a few repetitive sequences. Production values by, Sree Subrahmanyeshwara Cinemas, were decent and were within the limitations of a midrange romantic comedy film. Let’s discuss the work of the writer and the director, Yadunaath Maruthi Rao, in detail in the analysis section.

Positives:

1. First Half

2. Comedy Portions

3. Sree Vishnu & Satya’s Timing

4. Cinematography

Negatives:

1. Second Half

2. Lack of Strong Emotions

3. Music

Analysis:

The debutant writer and the director, Yadunaath Maruthi Rao, wrote a so-called peculiar characterisation of the female lead in the film and tried to generate enough fun moments using the comedy timing of his lead actor, Sree Vishnu and the lead comedian, Satya. Right from the word go, the writer intended only to make the audience laugh at any cost, and in doing so, he succeeded in parts but would have done a better job in other parts, especially the latter part of the second half. The film had at least five to six notable actors but for some reason, the director only concentrated on generating fun by using his lead actor.

The entire first half of the film unfolded without any major complaints. There were enough comedy sequences in the first half that engaged the audience in a fairly decent manner and the revelation of the conflict point during intermission, worked as well. However, after the initial few minutes of the second half, the film got into repetitive mode and the drama during the last thirty minutes was the film was written and executed in a very unexciting manner without any proper emotional depth. The twist during the climax was very predictable and it was narrated in a bland and rushed manner. Better care in writing and execution during the second half would have elevated the film’s overall graph.

The bare minimum that the audience expects from debutant writers and directors is original characters and characterisations, isn’t it? In Vishnu Vinyasam, to a crucial character, it was surprising to see a debutant director use the characterisation of ‘Jagadamba Chowdary’, a character from Ravi Teja’s movie Venky. Also, at just around two hours of runtime, the film makes the audience feel monotonous with a few repetitive sequences. One of the major negative points of the film is the songs. For a romantic comedy film to work, it is necessary to have at least one or two chartbuster songs. Unfortunately, none of the songs composed by, Radhan, helped the film in any way.

Overall, the core point of, Vishnu Vinyasam, has enough potential to become a very engaging romantic drama film. But, the half-hearted effort from the writer, director and the music director, ended up making it a decent watch. You may give it a try watching for a few well-executed comedy portions, Sree Vishnu and Satya’s timing.

Final Verdict – Partly Entertaining

Rating – 2.5/5

Related

-

World2 days ago

World2 days agoExclusive: DeepSeek withholds latest AI model from US chipmakers including Nvidia, sources say

-

Massachusetts2 days ago

Massachusetts2 days agoMother and daughter injured in Taunton house explosion

-

Montana1 week ago

Montana1 week ago2026 MHSA Montana Wrestling State Championship Brackets And Results – FloWrestling

-

Oklahoma1 week ago

Oklahoma1 week agoWildfires rage in Oklahoma as thousands urged to evacuate a small city

-

Louisiana5 days ago

Louisiana5 days agoWildfire near Gum Swamp Road in Livingston Parish now under control; more than 200 acres burned

-

Technology6 days ago

Technology6 days agoYouTube TV billing scam emails are hitting inboxes

-

Denver, CO2 days ago

Denver, CO2 days ago10 acres charred, 5 injured in Thornton grass fire, evacuation orders lifted

-

Technology6 days ago

Technology6 days agoStellantis is in a crisis of its own making