Entertainment

Review: ‘Little Fires Everywhere’ author Celeste Ng ventures boldly into the dark future

On the Shelf

‘Our Lacking Hearts’

By Celeste Ng

Penguin Press: 352 pages, $29

For those who purchase books linked on our web site, The Instances might earn a fee from Bookshop.org, whose charges assist unbiased bookstores.

On the entrance to the Planet Phrase museum in Washington, D.C., stands a outstanding sculpture designed to resemble a weeping willow. Nevertheless, as an alternative of leaves, Rafael Lozano-Hemmer’s tree has tiny audio system drooping from every department that play 360 totally different spoken languages, making a deliberate Tower of Babel, a cacophony of voices that immerses guests in our shared human want for expression.

If you end Celeste Ng’s gorgeous new dystopian novel, “Our Lacking Hearts,” you’ll perceive why this sculpture involves thoughts. The only option to put it with out spoiling something is to say that on the core of Ng’s narrative — a 12-year-old boy’s epic quest to seek out his lacking mom — is the all-important query of how we talk.

Sure, Noah Gardner, whose mom known as him Fowl, will depart residence, endure trials and carry out feats, identical to any classical hero. However Ng — whose spectacular 2014 debut, “Every thing I By no means Instructed You,” was adopted by 2017’s equally trenchant “Little Fires In all places” — roots her hero’s journey in books and libraries.

Fowl’s mom, Margaret Miu, a daughter of Chinese language immigrants, is a poet of some stature whose profession ended when america took a flip into onerous xenophobia and handed PACT. The Preserving of American Cultures and Traditions Act encourages bigotry towards many teams, significantly Asian Individuals, partly in response to China’s more and more highly effective position within the world economic system after “The Disaster.”

After Margaret’s disappearance, Fowl’s father loses his prestigious place as a linguistics professor. Given a low-level archives job, he should transfer together with his son to a tiny residence the place they face every day with grim resignation. Fowl’s major comfort is a buddy named Sadie, whose reminiscences of her storytelling mother and father fill Fowl with longing. He remembers his personal mom’s tales, and, after receiving a wierd missive from her — a web page lined with drawings of cats — he additionally remembers a ebook she as soon as learn to him. The clues start to represent a treasure map, resulting in the native library he’s been discouraged from visiting.

There, a librarian by chance reveals that her assortment can also be a means of transmitting messages to underground fighters. Many members of the resistance use vivid crimson hearts of their campaigns (comparable to a truck full of heart-marked pingpong balls dumped in a river) in a nod to Margaret’s best-known poetry assortment, “All Our Lacking Hearts.”

In essence, his mom’s poetry turns into a weapon, a software of resistance — and likewise a means again to her. Naturally, an epic hero wants a deputy; Fowl’s first act is to seek out Sadie, who has been taken from her residence — her Black mom was routinely suspect — and despatched to reside with a set of bland, compliant foster mother and father.

Certainly one of Ng’s most poignant tips on this novel is to bury its central tragedy — the forcible separation of kids from their mother and father — in the midst of the motion. This raises the narrative from the particular story of a confused boy and his defeated father to a mirrored image on the common bond between mother and father and youngsters, a core worth sacrificed on the pyre of Ng’s populist authoritarianism.

Sadie is greater than an archetypal sidekick; she is a prod to motion. Juggled between foster mother and father, the rebellious younger lady has at all times discovered methods to remain true to her upbringing. Early on, she minimize her personal mass of curly hair with kitchen shears quite than endure a caretaker’s comb. Even in early adolescence, Sadie believes in resistance, and he or she believes her mother and father (and Fowl’s) belong to it. “She’s considered one of them,” Sadie insists to Fowl. “She’s on the market someplace … Similar to my mother and father.”

As Fowl ventures into hazard, we start to know his father’s excessive warning and worry otherwise; he appears much less a person shut down by adversity and extra a valiant protector of his son. We additionally perceive what typically grounds true rebel: Sadie, like Fowl, has recognized parental love, the type that enables folks to cease fearing “What if?” and begin insisting “Even when … “

Issues get a lot busier within the second half of “Our Lacking Hearts.” Fowl and Sadie wind up in a Manhattan as chaotic as ever, although even scarier, sheltered by a wealthy eccentric from Margaret’s previous (primarily the deus ex machina right here). Coming collectively, even in small communities, makes a distinction throughout darkish instances. All of us perceive that now, having hunkered down with pandemic pods of our personal. Comrades encourage bravery in large and little methods.

That is the place Margaret departs from her personal group. Sure, she’s nonetheless alive, and sure, she’s been on the run; neither of these details spoils the ebook’s denouement. Margaret reminds us of true ethical braveness, plotting a nonviolent however extremely efficient scheme to disrupt the PACT regime. As Ng tells us on the finish of an Creator’s Be aware, “Václav Havel’s traditional 1978 essay ‘The Energy of the Powerless’ modified my excited about the impression a single particular person might have in dismantling a long-established system. I hope he’s proper.”

Like a lot of her fellow writers of dystopian fiction, together with Margaret Atwood, P.D. James, Philip Okay. Dick and Hillary Jordan, Ng harnesses the facility of the David-and-Goliath story — a prototypical quest story that has the advantage of possibly being actual. Or if it isn’t, it accords with historical past. The asymmetrical energy of a smaller group pitted towards a big, corrupt state is greater than only a nice storytelling trope. It has occurred many instances in recorded historical past. It’s occurring at this time, as an illustration in Ukraine.

Whereas briefly reunited together with his mom — this ebook can also be a parent-child love story — Fowl believes Margaret when she says she is going to return to him after she’s achieved her mission. However we already perceive that the federal government will discover her. We additionally know that, whereas she acted alone, she isn’t the lone resister. Others exist; others will stand up.

The writer concludes with the identical managed tone that opened the novel, exhibiting us a brand new technology of resisters, together with Fowl and Sadie and their confreres, who begin to consider what comes subsequent for them as pals and human beings. “Our Lacking Hearts” will land otherwise for particular person readers. One component we shouldn’t miss is Ng’s daring reversal of the biblical story of the Tower of Babel. It’s the drive for conformity, the suppression of our wonderful cacophony, that may doom us. And it’s the expression of particular person souls that may save us.

Patrick is a contract critic who tweets @TheBookMaven.

Movie Reviews

Catherine Breillat Is Back, Baby

The transgressive French filmmaker is in fine, fucked-up form with Last Summer, about a middle-age lawyer who starts sleeping with her stepson.

Photo: Janus Films

When Anne (Léa Drucker) has sex with her 17-year-old stepson, she closes and sometimes covers her eyes. It’s a pose that brings to mind what people say about the tradition of draping a napkin over your head before eating ortolan, that the idea is to prevent God from witnessing what you’re about to do. Théo (Samuel Kircher) is as fine-boned as any songbird — “You’re so slim!” Anne gasps in what sounds almost like pain during one of their encounters, as she runs her hands up his rangy torso — and just as forbidden. And despite the fact that what she’s doing could blow up her life, she can’t stay away. It wouldn’t be fair to say that desire is a form of madness in Last Summer, a family drama as masterfully propulsive as a horror movie. Anne remains upsettingly clear-eyed about what’s happening, as though to suggest otherwise would be a cop-out. But desire is powerful, enough to compel this bourgeois middle-age professional into betraying everything she stands for in a few breathtaking turns.

Last Summer is the first film in a decade from director Catherine Breillat, the taboo-loving legend behind the likes of Fat Girl and Romance. Last Summer, which Breillat and co-writer Pascal Bonitzer adapted from the 2019 Danish film Queen of Hearts, could be described as tame only in comparison to Rocco Siffredi drinking a teacup full of tampon water in Anatomy of Hell, but there is a lulling sleekness to the way it lays out its setting that turns out to be deceptive. Anne and her husband Pierre (Olivier Rabourdin) live with their two adopted daughters in a handsome house surrounded by sun-dappled countryside, a lifestyle sustained by the business dealings that frequently require Pierre to travel. Anne’s sister and closest friend Mina (Clotilde Courau) works as a manicurist in town, and conversations between the two make it clear that they didn’t grow up in the kind of ease Anne currently enjoys. It’s a luxury that allows her to pursue a career that seems more driven by idealism than by financial concerns. Anne is a lawyer who represents survivors of sexual assault, a detail that isn’t ironic, exactly, so much as it represents just how much individual actions can be divorced from broader beliefs.

In the opening scene, Anne dispassionately questions an underage client about her sexual history. She informs the girl that she should expect the defense to paint her as promiscuous before reassuring her that judges are accustomed to this tactic. The sequence outlines how familiar Anne is with the narratives used to discredit accusers, but also highlights a certain flintiness to her character. Drucker’s performance is impressively hard-edged even before Anne ends up in bed with her stepson. There’s a restlessness to the character behind the sleek blonde hair and businesswoman shifts, a desire to think of herself as unlike other women and as more interesting than the buttoned-up normies her husband brings by for dinner. Anne enjoys her well-coiffed life, but she also feels impatient with it, and when Théo gets dropped into her lap after being expelled from school in Geneva for punching his teacher, he triggers something in her that’s not just about lust. Théo is still very much a kid, something Breillat emphasizes by showcasing the messes he leaves around the house as much as on his sulky, half-formed beauty. But that rebelliousness speaks to Anne, who finds something invigorating in aligning herself with callow passion and impulsiveness instead of stultifying adulthood — however temporarily.

This being a Breillat film, the sex is Last Summer’s proving ground, the place where all those tensions about gender and class and age meet up with the inexorability of the flesh. The first time Anne sleeps with Théo, it’s shot from below, as though the camera’s lying in bed beside the woman as she looks up at the boy on top of her. It’s a point of view that makes the audience complicit in the scene, but that also dares you not to find its spectacle hot. Breillat is an avid button-pusher responsible for some of the more disturbing depictions of sexuality to have ever been committed to screen, but Last Summer refuses to defang its main character by portraying her simply as a predatory molester. Instead, she’s something more complicated — a woman trying to have things both ways, to dabble in the transgressive without risking her advantageous perch in the mainstream, and to wield the weapons of the victim-blaming society she otherwise battles when they are to her advantage. It’s not the sex that harms Théo; it’s the mindfuck of what he’s subjected to. After dreamily playing tourist in Théo’s youthful existence, Anne drags him into the brutal realities of the grown-up world. The results are unflinching and breathtakingly ugly. You couldn’t be blamed for wanting to look away.

See All

Entertainment

Review: In the underpowered 'Daddio,' the proverbial cab ride from hell could use more hell

The art of conversation has been a casualty in these deeply divided days of ours, and the poor state of talk in the movies — so often expositional, glib or posturing — is an unfortunate reflection of that. The new film “Daddio” is an attempt to put verbal discourse front and center, confining to a yellow taxi a pair with different life paths, as you would expect when your leads are Sean Penn and Dakota Johnson. (Guess which one is the cabbie.)

Johnson’s coolly elegant, nameless traveler, a computer programmer returning to New York’s JFK airport from a trip visiting a big sister in Oklahoma, may be getting a flat rate for her journey, but the meter’s always running on the mouth of Penn’s gleefully crusty and opinionated driver, Clark. He’s a twice-married man prone to streetwise philosophizing about the state of the world and, over the course of the ride, the unsettled romances of his attractive fare. And as she drops clues about her life — sometimes unwittingly, then a little more freely — she gives back with some probing responses of her own, trying to pry him open.

Writer-director Christy Hall, who originally conceived the scenario as a stage play, lets the chatter roll — there’s a significant stretch in which the cab isn’t even moving. And when silence sets in, there’s still an exchange to tend to, as Johnson occasionally, with apprehension, responds to a lover’s insistent sexting. This third figure (unseen, save one predictable picture sent to her phone) becomes another source of conjectural bravado for Clark, a self-proclaimed expert in male-female relations, who makes eye contact through the rearview mirror.

Sean Penn in the movie “Daddio.”

(Sony Pictures Classics)

Watching the unremarkable “Daddio,” you’ll never worry that anything untoward or combustible will happen between the chauvinist driver with a heart of gold and the smart if vulnerable young female passenger who “can handle herself,” as Clark frequently observes. That lack of tension is the problem. The movie is less about a nuanced conversation between strangers than a writer’s careful construction, designed to bridge a cultural impasse between the sexes. Hall is so eager to stage a big moment that upends expectations and triggers wet-eyed epiphanies — He’s a compassionate blowhard! She can laugh at his crassness! — that we’re never allowed to feel the molecules shift from moment to moment in a way that isn’t unforced. Life may be the subject, but life is what’s missing.

It doesn’t help that in directing her first feature, Hall has given herself one of the hardest jobs, getting the most out of only two ingredients and one container. It’s probably why Jim Jarmusch went the variety route with five different tales for his memorable 1991 taxi suite “Night on Earth.” That film conveyed a palpable sense of time and space.

“Daddio,” on the other hand, is nowhere near as assured visually or in its pacing. Hall has an experienced cinematographer in Phedon Papamichael (“Nebraska,” “Ford v Ferrari”) but chooses an unfortunate studio gloss that suggests utter control, rather than a what-might-happen vibe. Not that there’s anything wrong with a movie so clearly made on a set. But Johnson’s well-rehearsed poise and Penn’s coasting boldness make them seem like the stars of a commercial for a scent called Common Ground rather than flesh-and-blood people. At times, they hardly seem to be sharing the same car interior, leaving “Daddio” feeling like a safe space, when what it needs is danger.

‘Daddio’

Rating: R, for language throughout, sexual material and brief graphic nudity

Running time: 1 hour, 41 minutes

Playing: In limited release Friday, June 28

Movie Reviews

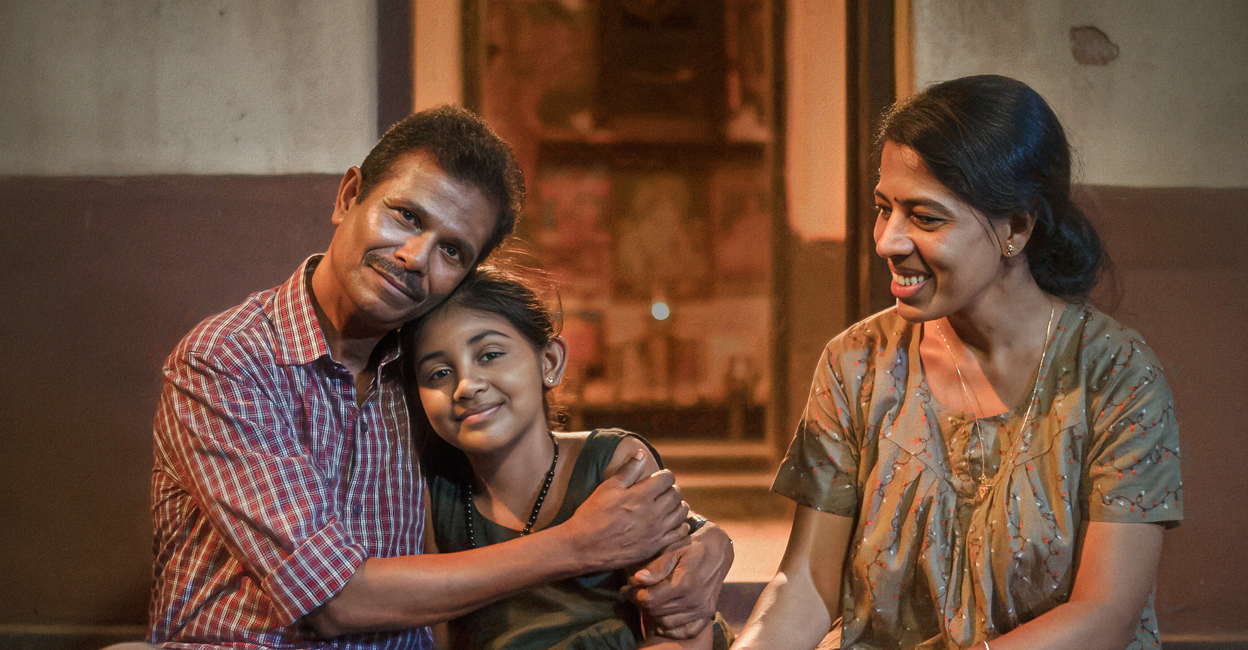

‘Kunddala Puranam’ Review | A simplistic tale featuring an in-form Indrans, Remya Suresh

‘Kunddala Puranam’, starring Indrans and Remya Suresh in the lead, is the kind of movie you might want to watch for its focus on village folk and their everyday lives, offering a break from the bustling city. However, its far too simplistic approach may not work for all, especially at a time when filmmakers are trying to break new ground with experimental storytelling, unique styles, and mixing genres.

‘Kunddala Puranam’, directed by Santhosh Puthukkunnu, is set in Kasaragod, where a family opens up their private well to their neighbors. The well is an often-used trope in Malayalam cinema, with women characters gathering around it for water and some gossip. Venu (Indrans) and Thankamani (Remya Suresh) have a school-going daughter who yearns to wear gold earrings but can’t because of an ear infection. When her condition improves, Venu, who works as a security guard at a local bar, decides to purchase a pair for her. The gold earrings soon become the source of both happiness and unhappiness for the family.

The Kasaragod dialect, explored in films since the latter half of the last decade, has a certain charm, but what is particularly interesting is how Indrans effortlessly mouths his dialogues in the dialect. He is a masterclass in emotional acting and nails his role as a resolute father in this film. Remya Suresh, who played a prominent role in last year’s acclaimed movie ‘1001 Nunakal’, performs exceptionally well in this movie. Unni Raja, best known for ‘Thinkalazhcha Nishchayam’, also plays an interesting character. However, it is the child actor Sivaani Shibin who manages to capture the audience’s hearts with her playful innocence, a quality sadly missing in characters written for children in recent years.

Though the writers have tried their hand at humor in the movie, most of the dialogues fall flat, except for some scenes involving a drunkard and the other villagers. The story, though interesting, is stretched too long for comfort. Sound designer and musician Blesson Thomas manages to capture the mood of the story well through his music.

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoNYC pastor is sentenced to 9 years for fraud, including taking a single mom's $90,000

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoRead the Ruling by the Virginia Court of Appeals

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoTracking a Single Day at the National Domestic Violence Hotline

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoOrbán ally-turned-rival joins EPP group in European Parliament

-

Fitness1 week ago

Fitness1 week agoWhat's the Least Amount of Exercise I Can Get Away With?

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoSupreme Court upholds law barring domestic abusers from owning guns in major Second Amendment ruling | CNN Politics

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoTrump classified docs judge to weigh alleged 'unlawful' appointment of Special Counsel Jack Smith

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoSupreme Court upholds federal gun ban for those under domestic violence restraining orders

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/pmn/YE6IIODUERBWVOQEYG5BI3T5CE.jpg)