Entertainment

Review: How one writer learned to live with her deplorable ancestors

On the Shelf

Ancestor Hassle: A Reckoning and a Reconciliation

By Maud Newton

Random Home: 400 pages, $29

In the event you purchase books linked on our website, The Instances might earn a fee from Bookshop.org, whose charges help unbiased bookstores.

What can we owe our ancestors, and what declare have they got on us? How can we shoulder the legacy of their shortcomings, sins and crimes? These questions cloud our nation’s historical past and canine the conscience of anybody who has wandered into the weeds of Ancestry.com and came upon a handwritten will revealing that their forebears owned slaves (and parceled them out to their youngsters once they died). Family tree websites like Ancestry, which meld DNA testing and an enormous laptop base of information and analysis, have opened the door to tales of quiet heroism, closeted villainy and unimaginable ache.

For her principally revelatory new memoir, “Ancestor Hassle,” blogger, critic and essayist Maud Newton has spent the final a number of years reckoning with the non-public and historic legacy of her ancestors, beginning along with her fractured speedy household and dealing backward in time, by and past her great-grandparents.

In Newton’s beginning household, some breaks have by no means healed. She’s completely estranged (and disinherited) from her father, a Mississippi-raised lawyer who thought-about slavery “a benevolent establishment that ought to by no means have been disbanded,” who painted out the faces of the brown youngsters in her storybooks (along with her mother’s nail polish, for those who’re questioning). For seven years, she didn’t discuss to her mom, an evangelical Christian minister, as a result of her mother refused to acknowledge the hurt executed by the truth that at age 12, Maud was molested by her stepfather. “I beloved my mom with a ferocious depth and wished her to be proper,” she writes. The wrongness of her mom’s blindness was devastating.

The additional again Newton goes, the extra hair-raising it will get. Her paternal grandparents, rich plantation house owners who relied on Black labor to work the fields, brokered cotton within the Mississippi city the place Emmett Until was lynched. Her fourth-great-grandfather prospered from shopping for and promoting slaves. Her maternal grandfather, a bipolar Texas Lothario who was married no less than 10 occasions, was shot within the abdomen by certainly one of his wives, and her maternal great-grandfather killed a person with a hay hook. One New England ancestor grew rich from dishonest Native People out of their land; one other was regarded as a witch.

That is wealthy materials for a soul-searching memoir, however in “Ancestor Hassle,” Newton goals for greater than an accounting of household secrets and techniques. She surveys and synthesizes what we all know at the moment about inheritance, a wealth of recent information derived from the sequencing of the human genome and the explosion of genetic analysis that adopted. Her seek for her private legacy leads down a number of roads (and plenty of blind alleys) as Newton items collectively the lives of lengthy useless family members from newspaper tales, metropolis directories and affected person registers at insane asylums. Her journey is by turns revelatory, humorous and exquisitely unhappy, as she tries to know the fraying of what have been as soon as the sturdy and loving bonds of household.

Newton’s technique in every of eight sections (“Nature and Nurture,” “Physicality,” “Temperament,” and so on.) is to start out with a give attention to the non-public — a grandfather’s psychological sickness, a grandmother’s hyperthyroidism. She then goes huge and deep into historical past, theology, tradition and science, returning to puzzle out what it means for her. There are chapters on the event of genetics, the eugenics motion, the heritability of household traits and the sector of epigenetics, which research whether or not our genes may be altered by expertise (quick reply: it’s difficult).

This mixture of non-public revelation and synthesis works, for essentially the most half. Newton is a logical thinker and a hyperacute observer, with a prodigious reminiscence and a lacerating honesty. She’s a clear and at occasions lyrical author: A grandmother’s ring, which she inherited and misplaced, was “the Platonic supreme of a ruby, the colour of blood from a prick take a look at.”

She balances blame with credit score. “What I’ve longed for many in my life is to be like my mother: inventive, unique, joyfully intractable,” she writes. “What I’ve feared most, too, is being like her: impulsive, fervent, self-destructive, and rebellious, pouring myself into tasks I later burn down.”

In an act of generosity, Newton lays her writing capacity on the toes of her father and his household, “the way in which I return to topics many times, from completely different angles, explaining my ideas and emotions to myself as I am going after which constructing them into an argument to fulfill myself and anybody else who may, alongside the way in which, be persuaded.”

It’s disquieting, then, when after many pages of lucid observations, she goes off the rails with regards to ancestor worship — its historic origins and fashionable incarnations. Newton indicators on to the notion that her ancestors are on the market, prepared and keen to present recommendation. She takes an “ancestor-veneration course for inexperienced persons” (out there in New Orleans; Brooklyn; Asheville, N.C.; and Portland, Ore.), which purports to assist members attain out to their forebears for help.

Course supplies contend, “Along with supporting repairs with residing household, our ancestors encourage wholesome vanity and assist us to make clear our future, relationships, and work on the planet.” (Right here I used to be attempting to think about my paternal grandparents, who raised 10 youngsters on a hardscrabble Tennessee farm, bolstering my vanity from past the veil.) This seek for one’s “effectively” family members and lineages, taking care to evade the damaging “unwell” useless, leads in Newton’s case to an encounter with an ancestor-linked spirit that apparently wandered over from the Disney studio lot, “a kind of fairy insect….she had a fats blue-green physique like a caterpillar, giant blue wings, and a blue human face.”

It’s as if Newton’s analytical thoughts took a vacation within the battle to make her contradictory emotions come collectively. This deviation in tone and intent, so late within the ebook, throws the reader. If household reconciliation is the aim, the outcomes really feel sadly incomplete.

However then, how is reconciliation potential with out reciprocity? Newton and her residing household can nonetheless apologize, atone, however failing woo-woo rituals, the opposite ancestors can not. Nor can their descendants accomplish that on their behalf.

Newton is on a journey, and maybe her seek for ancestor spirits is one cease on the highway. She believes answering for her ancestors’ sins is important — she helps organizations that assist Native folks reclaim land — however find out how to absolutely account for such huge injustice stays a fraught query. “I’m solely starting — and nonetheless pondering how — to make amends,” she writes.

On a chilly December day, she visited the house of her ninth great-grandparents in Massachusetts, individuals who appropriated Fatherland and grew rich from it. “The place felt somber and misguided, a doubtful monument that needs to be rethought,” she wrote. “I requested forgiveness of the land and its Native folks, residing and useless. On the worn dust on the foot of a bench, I emptied a bottle of wine as an providing.”

Gwinn, a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist who lives in Seattle, writes about books and authors.

Movie Reviews

'Federer: Twelve Final Days' movie review: Federer’s sweet swansong is fascinating

July 3, 2022, was a Sunday for the ages. Having greeted all past champions at Wimbledon’s Centre Court with warmth and respect, the crowd erupted in frenzied joy and delivered a standing ovation as an eight-time champion walked into the arena. The same spirits which were lifted when the master raised hopes of a last hurrah at Wimbledon, were devastated months later when Roger Federer decided to hang his boots.

Asif Kapadia and Joe Sabia’s directorial venture Federer: Twelve Final Days is a gripping account of Federer’s final few days before retirement. Federer, a global tennis icon and arguably the biggest superstar of the game, plunged tennis fans into collective mourning with the shocking news, while the Alps shed its tears with bountiful rains. As he retires in view of his repeated knee surgeries and advancing age, he plans a grand exit.

The audience relives the iconic Laver Cup in London, where Federer caught up with arch-rivals Rafael Nadal, Novak Djokovic and other tennis stars on September 23, 2022, for a sweet swansong.

Interspersed with layers of old clips displaying his unmatched elegance on and off the court, the documentary’s biggest strength is its deep emotional connect. With timely interviews by the greatest of his rivals, his wife and parents, the audience gets a glimpse of Federer’s two roles — a sporting legend and a devout family man.

What stands out is the Swiss master’s bonhomie with his biggest rival Nadal. Despite only a few days to go for his wife’s first delivery, Nadal still makes it to London for Federer’s farewell. With the camaraderie, the duo gives sporting rivalry a refreshingly newer, nobler perspective. Being the oldest of the lot, Federer comes out as a class act when he says, “It feels right that of all the guys here, I am the first to go.”

However, with its emphasis on nuances, the documentary is best suited for a niche audience. The general public, who might be curious to discover Federer’s legacy before appreciating it fully, may be left a tad disappointed.

Editing by Avdhesh Mohla is top notch as it does justice to Federer’s majestic on-court grace. With slick visuals and a fine script, the documentary does justice to Federer’s legacy, which, as Nadal says “Will live forever.”

It’s a must-watch if you are a Federer fan. But even if not, don’t miss it as Federer was for decades synonymous with tennis.

Cut-off box – Federer: Twelve Final Days

English (Prime Video)

Director: Asif Kapadia Joe Sabia

Rating: 4/5

Published 29 June 2024, 01:17 IST

Entertainment

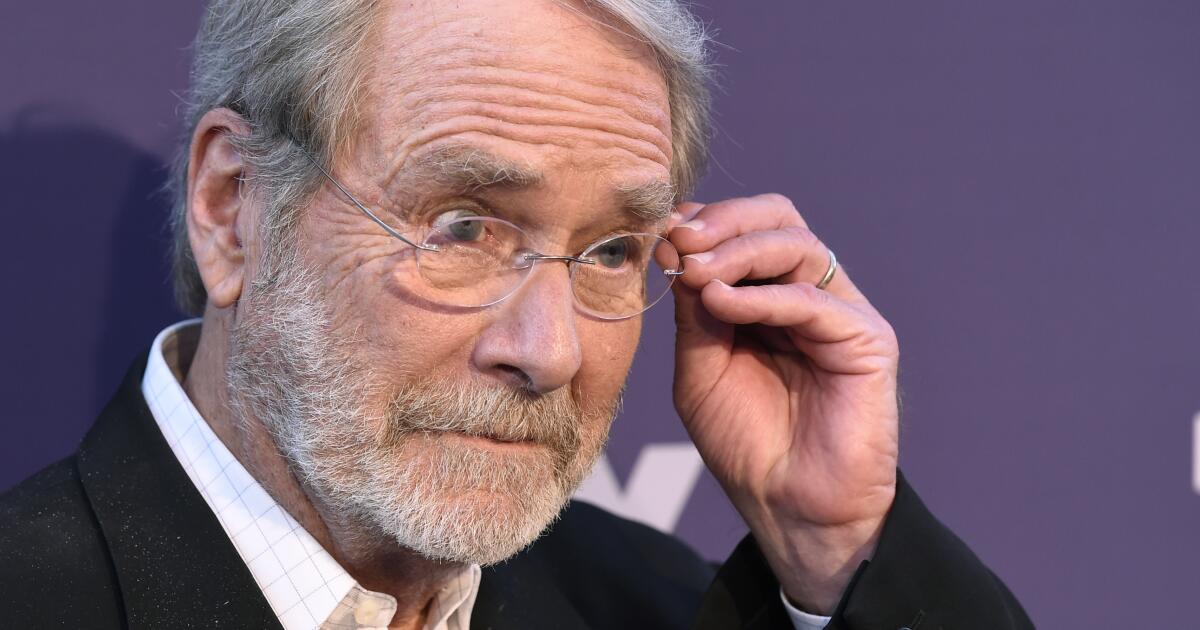

Martin Mull, comic actor, 'Roseanne' star and painter, dies at 80

Martin Mull, the comedic actor best known for his roles in “Clue,” “Roseanne,” “Arrested Development” and “Sabrina the Teenage Witch,” died Thursday. He was 80.

His daughter, TV writer and producer Maggie Mull, shared the news on Instagram.

“He was known for excelling at every creative discipline imaginable and also for doing Red Roof Inn commercials,” she wrote. “He would find that joke funny. He was never not funny. My dad will be deeply missed by his wife and daughter, by his friends and coworkers, by fellow artists and comedians and musicians, and — the sign of a truly exceptional person — by many, many dogs.”

Mull, who was also a singer-songwriter, rose to fame in the 1970s on Norman Lear’s satirical soap opera “Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman” and its spinoffs, “Fernwood 2 Night” and “America 2-Night.”

The dry-witted comic played Colonel Mustard in the 1985 comedy “Clue” and Teri Garr’s boss in 1983’s “Mr. Mom.” He was Roseanne’s boss, Leon Carp, on her titular sitcom, private detective Gene Parmesan on “Arrested Development” and “Sabrina the Teenage Witch’s” nosy Principal Kraft, in addition to voicing characters on animated shows, including “American Dad!” and “The Simpsons.”

The actor appeared in more than 200 Los Angeles Times articles across four decades. most recently in December. Following the death of Lear, a Times roundup of seven essential Lear shows noted Mull’s contributions to the oddball gallery of characters in “Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman.”

Here’s a sampling of headlines from Mull’s life as actor and as painter. A full Times appreciation is forthcoming.

Movie Reviews

Catherine Breillat Is Back, Baby

The transgressive French filmmaker is in fine, fucked-up form with Last Summer, about a middle-age lawyer who starts sleeping with her stepson.

Photo: Janus Films

When Anne (Léa Drucker) has sex with her 17-year-old stepson, she closes and sometimes covers her eyes. It’s a pose that brings to mind what people say about the tradition of draping a napkin over your head before eating ortolan, that the idea is to prevent God from witnessing what you’re about to do. Théo (Samuel Kircher) is as fine-boned as any songbird — “You’re so slim!” Anne gasps in what sounds almost like pain during one of their encounters, as she runs her hands up his rangy torso — and just as forbidden. And despite the fact that what she’s doing could blow up her life, she can’t stay away. It wouldn’t be fair to say that desire is a form of madness in Last Summer, a family drama as masterfully propulsive as a horror movie. Anne remains upsettingly clear-eyed about what’s happening, as though to suggest otherwise would be a cop-out. But desire is powerful, enough to compel this bourgeois middle-age professional into betraying everything she stands for in a few breathtaking turns.

Last Summer is the first film in a decade from director Catherine Breillat, the taboo-loving legend behind the likes of Fat Girl and Romance. Last Summer, which Breillat and co-writer Pascal Bonitzer adapted from the 2019 Danish film Queen of Hearts, could be described as tame only in comparison to Rocco Siffredi drinking a teacup full of tampon water in Anatomy of Hell, but there is a lulling sleekness to the way it lays out its setting that turns out to be deceptive. Anne and her husband Pierre (Olivier Rabourdin) live with their two adopted daughters in a handsome house surrounded by sun-dappled countryside, a lifestyle sustained by the business dealings that frequently require Pierre to travel. Anne’s sister and closest friend Mina (Clotilde Courau) works as a manicurist in town, and conversations between the two make it clear that they didn’t grow up in the kind of ease Anne currently enjoys. It’s a luxury that allows her to pursue a career that seems more driven by idealism than by financial concerns. Anne is a lawyer who represents survivors of sexual assault, a detail that isn’t ironic, exactly, so much as it represents just how much individual actions can be divorced from broader beliefs.

In the opening scene, Anne dispassionately questions an underage client about her sexual history. She informs the girl that she should expect the defense to paint her as promiscuous before reassuring her that judges are accustomed to this tactic. The sequence outlines how familiar Anne is with the narratives used to discredit accusers, but also highlights a certain flintiness to her character. Drucker’s performance is impressively hard-edged even before Anne ends up in bed with her stepson. There’s a restlessness to the character behind the sleek blonde hair and businesswoman shifts, a desire to think of herself as unlike other women and as more interesting than the buttoned-up normies her husband brings by for dinner. Anne enjoys her well-coiffed life, but she also feels impatient with it, and when Théo gets dropped into her lap after being expelled from school in Geneva for punching his teacher, he triggers something in her that’s not just about lust. Théo is still very much a kid, something Breillat emphasizes by showcasing the messes he leaves around the house as much as on his sulky, half-formed beauty. But that rebelliousness speaks to Anne, who finds something invigorating in aligning herself with callow passion and impulsiveness instead of stultifying adulthood — however temporarily.

This being a Breillat film, the sex is Last Summer’s proving ground, the place where all those tensions about gender and class and age meet up with the inexorability of the flesh. The first time Anne sleeps with Théo, it’s shot from below, as though the camera’s lying in bed beside the woman as she looks up at the boy on top of her. It’s a point of view that makes the audience complicit in the scene, but that also dares you not to find its spectacle hot. Breillat is an avid button-pusher responsible for some of the more disturbing depictions of sexuality to have ever been committed to screen, but Last Summer refuses to defang its main character by portraying her simply as a predatory molester. Instead, she’s something more complicated — a woman trying to have things both ways, to dabble in the transgressive without risking her advantageous perch in the mainstream, and to wield the weapons of the victim-blaming society she otherwise battles when they are to her advantage. It’s not the sex that harms Théo; it’s the mindfuck of what he’s subjected to. After dreamily playing tourist in Théo’s youthful existence, Anne drags him into the brutal realities of the grown-up world. The results are unflinching and breathtakingly ugly. You couldn’t be blamed for wanting to look away.

See All

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoRead the Ruling by the Virginia Court of Appeals

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoTracking a Single Day at the National Domestic Violence Hotline

-

Fitness1 week ago

Fitness1 week agoWhat's the Least Amount of Exercise I Can Get Away With?

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoSupreme Court upholds law barring domestic abusers from owning guns in major Second Amendment ruling | CNN Politics

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoTrump classified docs judge to weigh alleged 'unlawful' appointment of Special Counsel Jack Smith

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoSupreme Court upholds federal gun ban for those under domestic violence restraining orders

-

World5 days ago

World5 days agoIsrael accepts bilateral meeting with EU, but with conditions

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoTrump VP hopeful proves he can tap into billionaire GOP donors