Entertainment

OpenAI's board rejects bid from Elon Musk-led group

The feud between Elon Musk and rival Sam Altman took a new turn on Friday when OpenAI’s board rejected a $97.4-billion offer by an investment consortium led by the Tesla chief executive.

“OpenAI is not for sale, and the board has unanimously rejected Mr. Musk’s latest attempt to disrupt his competition,” Bret Taylor, chair of OpenAI’s board of directors, said Friday in a statement.

San Francisco-based OpenAI, a nonprofit startup behind ChatGPT, has been seeking to become a for-profit business. It was co-founded by Altman, who is also the chief executive.

On Friday, Taylor said, “Any potential reorganization of OpenAI will strengthen our nonprofit and its mission to ensure AGI benefits all of humanity.”

Musk, an early investor in OpenAI, sued the nonprofit last year, alleging it was departing from its mission to benefit humanity.

The SpaceX chief executive also leads an AI startup, xAI, which competes against OpenAI.

Musk purchased social media company Twitter in 2022 for $44 billion and changed the name to X.

A Musk-led investment consortium on Monday announced its offer to buy OpenAI.

“If Sam Altman and the present OpenAI Inc. Board of Directors are intent on becoming a fully for-profit corporation, it is vital that the charity be compensated for what its leadership is taking away from it: control over the most transformative technology of our time,” said Marc Toberoff, an attorney representing the investors in a statement on Monday.

“It’s time for OpenAI to return to the open-source, safety-focused force for good it once was,” Musk said in a statement on Monday. “We will make sure that happens.”

Altman responded on X, saying, “no thank you but we will buy twitter for $9.74 billion if you want.”

In a court filing on Wednesday, Toberoff said that Musk will withdraw his bid if OpenAI’s board is “prepared to preserve the charity’s mission and stipulate to take the ‘for sale’ sign off its assets by halting its conversion.”

The Musk-led investment consortium that bid on OpenAI includes xAI Corp., Baron Capital Group Inc., Valor Management LLC, Atreides Management LP, Vy Fund III L.P. Eight Partners VC LLC and Ari Emanuel’s investment fund, Emanuel Capital Management LLC. Emanuel is chief executive of Beverly Hills-based entertainment and sports company Endeavor.

“They’re just selling it to themselves at a fraction of what Musk has offered, enriching Board members, Altman, [OpenAI Co-founder and President Greg] Brockman and others rather than the charity in a classic self-dealing transaction,” Toberoff said on Friday in an email. “Will someone please explain how that benefits ‘all of humanity’?”

Movie Reviews

Movie Review – The Testament of Ann Lee (2025)

The Testament of Ann Lee, 2025.

Directed by Mona Fastvold.

Starring Amanda Seyfried, Lewis Pullman, Thomasin McKenzie, Matthew Beard, Christopher Abbott, David Cale, Stacy Martin, Scott Handy, Jeremy Wheeler, Tim Blake Nelson, Daniel Blumberg, Jamie Bogyo, Viola Prettejohn, Natalie Shinnick, Shannon Woodward, Millie-Rose Crossley, Willem van der Vegt, Esmee Hewett, Harry Conway, Benjamin Bagota, Maria Sand, Scott Alexander Young, Matti Boustedt, George Taylor, Alexis Latham, Lark White, Viktória Dányi, and Roy McCrerey.

SYNOPSIS:

Ann Lee, the founding leader of the Shaker Movement, proclaimed as the female Christ by her followers. Depicts her establishment of a utopian society and the Shakers’ worship through song and dance, based on real events.

The second coming of Christ was a woman. Narrated as a story of legend and constructed as a cinematic epic, co-writer/director Mona Fastvold’s The Testament of Ann Lee tells the story of the eponymous 18th-century preacher who occasionally experienced divine visions guiding her on how to teach her and her followers to free themselves and be absolved of sin.

This group, an offshoot of Quakers known as Shakers, did so by stimulating and intoxicating full-body rhythmic dancing movements set to many hymns beautifully sung by Amanda Seyfried and others. The key distinction between the group, and arguably the toughest selling point of the film aside from the religious nature of it all, is that Ann Lee asserted that the only way to achieve such pure holiness is by giving up all sexual relations, living a life of celibacy (as evident by some laughter during the CIFF festival screening when she made this decree, which quickly subsided as it is relatively easy to buy into her mission and convictions).

It shouldn’t necessarily come as a surprise that Mona Fastvold had trouble getting this one off the ground. Perhaps what finally secured the project’s financial backing was all those awards The Brutalist (directed by her husband Brady Corbet and co-written by her, flipping those duties and credits this time around) either won or was nominated for, which was notably another film that almost no one had interest in making. The point is that this should serve as a reminder that there is an audience for anything and everything.

Whether one doesn’t care about religious movements or is a nonbeliever, The Testament of Ann Lee is remarkably hypnotic in its craftsmanship. It features a flat-out career-best performance from Amanda Seyfried, who blends all of her strengths as an actor and unleashes them at the peak of her talent. Yes, there are moments of tragedy and trauma, but the film refuses to wallow in misery, chartering her Shakers movement with hope, miracles, and perseverance as the journey takes them from Manchester to Niskayuna, New York, in search of expanding their follower base while dealing with other setbacks within the movement and personally.

Chronicling Ann Lee’s life with precise editing that rarely drags (and mostly fixates on the early stages of the Shakers movement and decade-plus long attempt to battle sexism as a female preacher and find a foothold amidst escalating tensions between British and Americans), the film also offers insight into the events that gave her a repulsion for sexual intimacy, her marriage with blacksmith Abraham (Christopher Abbott), and dynamics with her most loyal supporters which includes brother William (Lewis Pullman) and Mary (Thomasin Mckenzie, also serving as the narrator). Given the unfortunate nature of how most women, especially wives, were expected to have zero agency compared to their male counterparts and deliver babies, it is also organically inspiring watching her find a group with similar beliefs willing to trust her visions and take up celibacy. Whether or not all of them succeed is part of the journey and, interestingly enough, shows who is genuinely loyal and in her corner.

This is no dry biopic, though. Instead, it is brimming with life and energy, mainly through those “shaking” sequences depicting those outstandingly choreographed seizure-like dance numbers (typically shot by William Rexer from an elevated overhead angle, looking down at an entire room, capturing a ridiculous amount of motions all weaving together and creating something uniformly spellbinding). The songs throughout are divinely performed, adding another layer to this film’s transfixing pull. Nearly every image is sublime, right up until the perfect final shot. Admittedly, the film loses a bit of steam in the third act as one awaits a grim confrontation with naysayers who feel threatened by her position, movement, and pacifism regarding the burgeoning American Revolution.

Still, whatever reservations one has about watching a religious movement preaching peace and celibacy while laboring away building a utopia (an aspect that puts it in great juxtaposition with The Brutalist) will wash away like sin. That’s the power of the movies; even someone who isn’t religious will find it hard not to be swept up in Ann Lee’s life. Fact, fiction, bluff… it doesn’t matter; the material is treated with conviction and non-judgmental respect. In The Testament of Ann Lee, Amanda Seyfried channels that for something holy, empowering, infectious, and all around breathtaking.

Flickering Myth Rating – Film: ★ ★ ★ ★ / Movie: ★ ★ ★ ★

Robert Kojder

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=embed/playlist

Entertainment

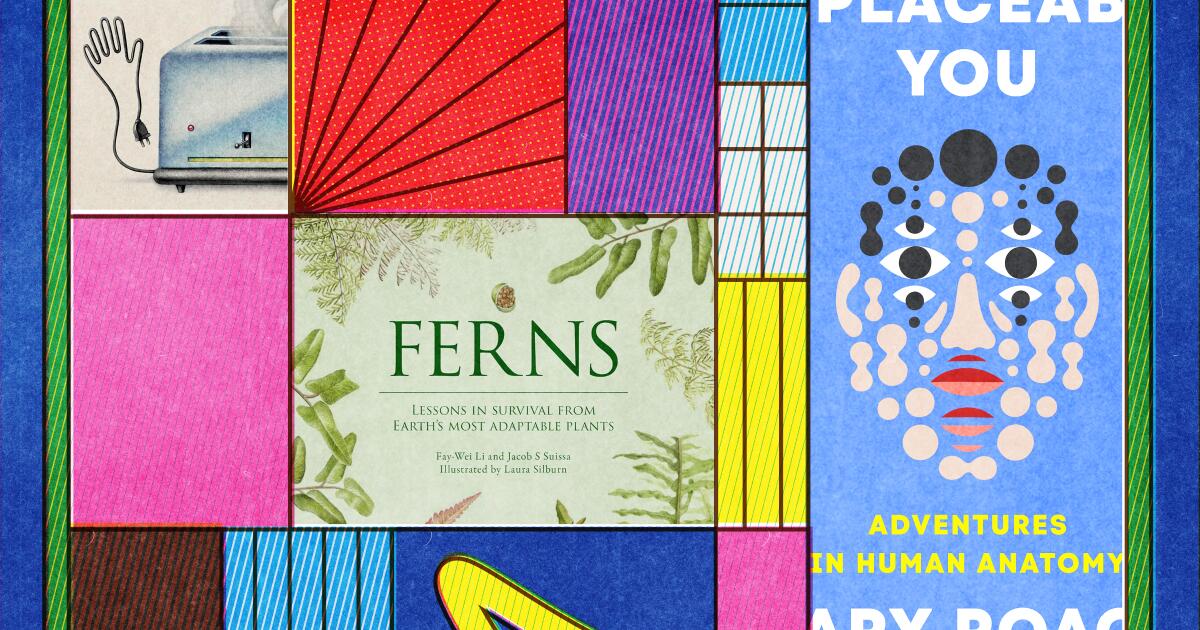

The 5 best science books of 2025

It’s been an uneasy year for science. While there were significant milestones, like breakthroughs in gene editing for rare diseases and novel insights into early human evolution (including fire-making), the U.S. science community at large was rocked by institutional challenges. Drastic federal cuts froze thousands of research grants, and the Trump administration began actively working to dismantle the National Center for Atmospheric Research. Meanwhile, fraudulent scientific research papers are on the rise — casting a shadow over academic integrity.

Our picks for this year’s best in arts and entertainment.

Thankfully, we can still turn to our bookshelves — and podcasts — to ground us. We tapped science doyenne Alie Ward, the host of the funny cult favorite “Ologies” podcast, to share her picks for the best science books of 2025.

Spanning fascinating subjects from bees to human anatomy, Ward’s insightful list reminds us that books remain a timeless vessel for truth and knowledge.

“Ferns: Lessons in Survival From Earth’s Most Adaptable Plants”

By Fay-Wei Li and Jacob S. Suissa

Hardie Grant Books: 192 pages, $45

“Dr. Li is the botanist of our dreams… the way he talks about ferns and why he loves them, and about growing up in Taiwan (in essentially a fern forest), and how the sexual reproduction of ferns has been a great way to draw attention to the LGBTQ and nonbinary community is so charming and funny. They even named a whole genus after Lady Gaga because they were listening to ‘Born This Way’ a lot in the lab and also because there are sequences in their DNA that are ‘GAGA.’

“Laura Silburn’s illustrations are gorgeous — they really put a lot of texture into some of these plants that are really tiny. Every page is like looking at a botany poster. As we’ve seen so much science research being underfunded, especially in the last year, there’s this big question by the culture at large of why does it matter? Why does studying the fern genome matter? It has real-world impacts — that’s fewer pesticides on your crops because we figured out something from a foreign genome. I always love when something is overlooked or taken for granted and because of someone’s passion and their dedication to studying it, we learn that it can change our lives.”

“The ABCs of California’s Native Bees”

By Krystle Hickman

Heyday: 240 pages, $38

“Krystle is an astounding photographer and an incredible visual artist. Her passion for native bees is infectious. A lot of people, when they think of bees, they think of honeybees. And honeybees are not even native to North America. They’re not native to L.A. They’re not native to this country. They’re feral livestock. What I love about her book is it opens your eyes to all of these species that are literally right under our noses that we wouldn’t even consider — and that a lot of people wouldn’t even identify as bees.

“The other reason why I love this book is that she puts these essays into it that are about her experiences going to find the bees. So you’re getting to see these gorgeous landscape pictures. You’re getting to see what it took to find the bee, how to look for it, and more about this particular species. It’s organized in these ABCs that you can pick up at any chapter and check out a bee you’ve never heard of before.”

(Little, Brown and Company)

“Humanish: What Talking to Your Cat or Naming Your Car Reveals About the Uniquely Human Need to Humanize”

By Justin Gregg

Little, Brown: 304 pages, $30

“Justin is hilarious. He is such a good writer, and his voice is really, really approachable. The way that he writes about science is through such a wonderful pop culture and pop science lens. You feel like you’re reading a friend’s email who just has something really interesting to tell you.

“This book is all about anthropomorphizing everything from our toasters to why we like some spiders but hate other spiders. This is a discussion that is so important in this time when we literally have bots on our phones that are like, ‘I’ll be your best friend.’

“Justin speaks to human psychology and our need to want to be friends or villainize objects —or technology or animals — and project our own humanity onto them in ways that are sometimes helpful and sometimes dangerous.

“As a science communicator, you can tell people the most fascinating facts and can give them the best stories. But unless you can give people a takeaway, then a lot of times it doesn’t stick or the interest isn’t there. He really addresses the question of ‘Well, what does this mean for my life?’”

“Replaceable You: Adventures in Human Anatomy”

By Mary Roach

W.W. Norton & Co: 288 pages, $28.99

“I’m a long term simp for Mary Roach.

“The humanity that she brings is such a wonderful base for how our bodies fail us sometimes and what we are trying to do to bring them back. From her being present during orthopedic surgeries and the way that she describes the sound of hammer on bone (and just the kind of jovial atmosphere in an operating room that, as a patient, you would never be clued in about because you are passed out half dead on a slab). She really soaks up a vibe that you would never have access to. She goes to Mongolia to learn about eye surgery there in yurts. She takes you to places you would never be able to go. She’s rooting around in archives and old papers — she just makes anything interesting.

“Mary really is both an ally and an outsider, and I think that that’s a really beautiful thing in her book.”

“The Double Tax: How Women of Color Are Overcharged and Underpaid”

By Anna Gifty Opoku-Agyeman

Portfolio: 256 pages, $29

“Anna Gifty Opoku-Agyeman is an absolute force. I’ve followed her work in economics and in equity for years, and I was really excited for this book to come out. We did an episode on kalology, which is the study of beauty standards, years ago and I have always loved the conversation of how different members of society have a certain tax on them — these extra resources that they are expected to provide.

“I was really excited to read about specifically women of color, because that is something that I don’t feel is discussed at large. Anna combines the sociology of it with the reality of her experience and other women of color. Because she is so deft when it comes to policy and economics, she also considers, ‘What can we do about this?’ It’s not just enough to discuss this, but what can be done?

“She has totals of what the gender gap is and what the double tax is, and it’s written up like a receipt. This book really addresses the double tax in a way that, even if you have no insight or it’s something that you haven’t thought about — or you are someone who hasn’t experienced this — it’s laying it out economically in a way that is really accessible and has a lot of impact.”

Recinos is an arts and culture journalist and creative nonfiction writer based in Los Angeles. Her first essay collection, “Underneath the Palm Trees,” is forthcoming in early 2027.

Movie Reviews

Movie Review: An electric Timothée Chalamet is the consummate striver in propulsive ‘Marty Supreme’

“Everybody wants to rule the world,” goes the Tears for Fears song we hear at a key point in “Marty Supreme,” Josh Safdie’s nerve-busting adrenaline jolt of a movie starring a never-better Timothée Chalamet.

But here’s the thing: everybody may want to rule the world, but not everybody truly believes they CAN. This, one could argue, is what separates the true strivers from the rest of us.

And Marty — played by Chalamet in a delicious synergy of actor, role and whatever fairy dust makes a performance feel both preordained and magically fresh — is a striver. With every fiber of his restless, wiry body. They should add him to the dictionary definition.

Needless to say, Marty is a New Yorker.

Also needless to say, Chalamet is a New Yorker.

And so is Safdie, a writer-director Chalamet has called “the street poet of New York.” So, where else could this story be set?

It’s 1952, on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. Marty Mauser is a salesman in his uncle’s shoe store, escaping to the storeroom for a hot tryst with his (married) girlfriend. Suddenly we’re seeing footage of sperm traveling — talk about strivers! — up to an egg. Which morphs, of course, into a pingpong ball.

This witty opening sequence won’t be the only thing recalling “Uncut Gems,” co-directed by Safdie with his brother Benny before the two split for solo projects. That film, which feels much like the precursor to “Marty Supreme,” began as a trip through the shiny innards of a rare opal, only to wind up inside Adam Sandler’s colon, mid-colonoscopy.

Sandler’s Howard Ratner was a New York striver, too, but sadder, and more troubled. Marty is young, determined, brash — with an eye always to the future. He’s a great salesman: “I could sell shoes to an amputee,” he boasts, crassly. But what he’s plotting to unveil to the world has nothing to do with shoes. It’s about table tennis.

This image released by A24 shows Timothée Chalamet in a scene from “Marty Supreme.” (A24 via AP)

How likely is it that this Jewish kid from the Lower East Side can become the very face of a sport in America, soon to be “staring at you from the cover of a Wheaties box?”

To Marty, perfectly likely. Still, he knows nobody in the U.S. cares about table tennis. He’s so determined to prove everyone wrong, starting at the British Open in London, that when there’s a snag obtaining cash for his trip, he brandishes a gun at a colleague to get it.

Shaking off that sorta-armed robbery thing, Marty arrives in London, where he fast-talks his way into a suite at the Ritz. Here, he spies fellow guest Kay Stone (Gwyneth Paltrow, in a wise, stylish return to the screen), a former movie star married to an insufferable tycoon (“Shark Tank” personality Kevin O’Leary, one of many nonactors here.)

Kay’s skeptical, but Marty finds a way to woo her. Really, all he has to say is: “Come watch me.” Once she sees him play, she’s sneaking into his room in a lace corselet.

This image released by A24 shows Gwyneth Paltrow in a scene from “Marty Supreme.” (A24 via AP)

This would be a good time to stop and consider Chalamet’s subtly transformed appearance. He is stick-thin — duh, he never stops moving. His mustache is skimpy. His skin is acne-scarred — just enough to erase any movie-star sheen. Most strikingly, his eyes, behind the round spectacles, are beady — and smaller. Definitely not those movie-star eyes.

But then, nearly all the faces in “Marty Supreme” are extraordinary. In a movie with more than 100 characters, we have known actors (Fran Drescher, Abel Ferrara); nonacting personalities (O’Leary, and an excellent Tyler Okonma (Tyler, The Creator) as Marty’s friend Wally); and exciting newcomers like Odessa A’Zion as Marty’s feisty girlfriend Rachel.

There are also a slew of nonactors in small parts, plus cameos from the likes of David Mamet and even high wire artist Philippe Petit. The dizzying array makes one curious how it all came together — is casting director Jennifer Venditti taking interns? Production notes tell us that for one hustling scene at a bowling alley, young men were recruited from a sports trading-card convention.

Elsewhere on the creative team, composer Daniel Lopatin succeeds in channelling both Marty’s beating heart and the ricochet of pingpong balls in his propulsive score. The script by Safdie and cowriter Ronald Bronstein, loosely based on real-life table tennis hustler Marty Reisman, beats with its own, never-stopping pulse. The same breakneck aesthetic applies to camera work by Darius Khondji.

Back now to London, where Marty makes the finals against Japanese player Koto Endo (Koto Kawaguchi, like his character a deaf table tennis champion). “I’ll be dropping a third atom bomb on them,” he brags — not his only questionable World War II quip. But Endo, with his unorthodox paddle and grip, prevails.

After a stint as a side act with the Harlem Globetrotters, including pingpong games with a seal — you’ll have to take our word for this, folks, we’re running low on space — Marty returns home, determined to make the imminent world championships in Tokyo.

But he’s in trouble — remember he took cash at gunpoint? Worse, he has no money.

So Marty’s on the run. And he’ll do anything, however messy or dangerous, to get to Japan. Even if he has to totally debase himself (mark our words), or endanger friends — or abandon loyal and brave Rachel.

This image released by A24 shows Odessa A’zion in a scene from “Marty Supreme.” (A24 via AP)

Is there something else for Marty, besides his obsessive goal? If so, he doesn’t know it yet. But the lyrics of another song used in the film are instructive here: “Everybody’s got to learn sometime.”

So can a single-minded striver ultimately learn something new about his own life?

We’ll have to see. As Marty might say: “Come watch me.”

“Marty Supreme,” an A24 release, has been rated R by the Motion Picture Association “for language throughout, sexual content, some violent content/bloody images and nudity.” Running time: 149 minutes. Four stars out of four.

-

Iowa1 week ago

Iowa1 week agoAddy Brown motivated to step up in Audi Crooks’ absence vs. UNI

-

Iowa1 week ago

Iowa1 week agoHow much snow did Iowa get? See Iowa’s latest snowfall totals

-

Maine7 days ago

Maine7 days agoElementary-aged student killed in school bus crash in southern Maine

-

Maryland1 week ago

Maryland1 week agoFrigid temperatures to start the week in Maryland

-

New Mexico6 days ago

New Mexico6 days agoFamily clarifies why they believe missing New Mexico man is dead

-

South Dakota1 week ago

South Dakota1 week agoNature: Snow in South Dakota

-

Detroit, MI1 week ago

Detroit, MI1 week ago‘Love being a pedo’: Metro Detroit doctor, attorney, therapist accused in web of child porn chats

-

Health1 week ago

Health1 week ago‘Aggressive’ new flu variant sweeps globe as doctors warn of severe symptoms