Movie Reviews

Netflix’s Carter puts action above all else

Netflix has launched many glitzy, action-filled episodic sequence this 12 months, together with All of Us Are Lifeless and Cash Heist: Korea. However its subsequent huge motion piece is a movie, Carter, which stars Joo Received within the main position. The often clean-cut heartthrob picture of Joo Received undergoes a startling transformation right here into the rugged, ruffian-like Carter (the namesake of the movie’s title). Carter is directed by Jung Byung-gil, who has made his profession out of his stylized, high-octane motion course in movies like The Villainess (2017) and Confession of Homicide (2012).

Viewers who’re searching for a strong motion movie will discover loads of thrills within the fascinating, sleekly edited Carter, the place its motion sequences are all woven collectively to provide the movie a “one take” impact. There are gorgeous aerial views of rooftop fights and waterfall escapes, alongside spine-tingling chases by dimly lit cavernous rooms — with the more and more acquainted backdrop of pressure between North and South Korea thrown in. What Carter units out to perform in motion, choreography, and set design, it pulls off with nice aplomb.

Nonetheless, these searching for a extra character-driven story or who’ve a decrease tolerance for lengthy, elaborate motion sequences may discover Carter’s 132-minute runtime a bit too overwhelming.

Carter begins with an exposition-heavy introduction, noting that the Korean peninsula is grappling with a dire infectious outbreak of the “DMZ virus.” The viral an infection creates “animal-like behaviors” and will increase violent tendencies within the contaminated. Leaders from North and South Korea are working collectively to create an antibody therapy utilizing the blood of Physician Jung’s daughter, named Ha-na, who was cured of the DMZ virus an infection by her father’s analysis. Nonetheless, Physician Jung (Jung Jae-young) and Ha-na (Kim Bo-min) go lacking throughout a switch association to North Korea, the place the physician was speculated to additional his analysis and mass-produce a remedy for the virus on the Sinuiju Chemical Weapons Institute. There, crowds of contaminated North Korean sufferers are additionally held in quarantine. In the meantime, Carter wakes up and finds a mysterious voice giving him directions by an earpiece. He has no alternative however to comply with by with the mission as he has a deadly bomb embedded in his mouth.

The DMZ virus outbreak takes place solely 10 months after a cease-fire between North and South Korea, with the armistice in delicate stability amid mistrust on each side over the botched switch of Physician Jung and Ha-na. The geopolitical backdrop and well being disaster present the required narrative stakes amid the movie’s nonstop whirlwind of motion. There may be additionally an entire solid of fascinating characters: overseas liaisons, North Korean Employees’ Celebration members, army leaders, intelligence brokers, infectious illness docs, and youngsters. Sadly, every of them is just flippantly used (excluding younger Ha-na); they exit as rapidly as they enter, leaving viewers to rue the missed alternatives to deepen the movie’s storytelling and character arcs.

There may be an acute sense in Carter that the motion will all the time take priority over character growth or well-crafted emotional turns. The movie additionally has a substantial quantity of gore, which feels extended and even indulged by the “one shot” type of the movie. At a number of factors in Carter, viewers could battle to seek out solutions to some basic questions within the sacred artwork of crafting a narrative: what’s presently driving the story’s protagonist, Carter, to tackle such a disproportionate quantity of danger? On the opposite facet, what are the explanations behind the antagonist’s choices? In essence, what’s the motivation behind the motion of every character?

One of many greatest speaking factors of Carter is the “single take” type that it was shot in. Whereas the movie is admittedly made up of a number of photographs, the general impact works. Because the movie breathlessly strikes from a public bathhouse to a bus, warehouse, medical facility, garments store, and airplane, simply to call a number of, the “single take” type offers Carter a sense of vastness in area that few motion movies have been capable of obtain. The digital camera tirelessly chases the equally industrious Carter by the bodily area, trapped collectively within the chaos and uncertainty. There may be neither reprieve supplied by an alternate angle nor further information gained by an establishing shot; the enemy can emerge from any course.

A number of sequences are a triumph of filmmaking, notably these involving autos hovering by a dizzying array of backdrops: a motorcycle chase scene by labyrinthian streets and alleyways, an airplane standoff that transforms right into a skydiving battle scene (which was shot with the actors actually skydiving) and a battle sequence involving vans and jeeps rushing by an agricultural panorama. Sequences are threaded collectively practically effortlessly — a stark distinction to the unimaginably labor-intensive work and planning that went into creating Carter. At instances, the movie seems like one big, tangled escape room recreation. There may be maybe a nagging query right here of whether or not Carter’s cinematic accomplishments are wasted on the small screens that Netflix’s audiences will encounter the movie, as all the trouble could not absolutely translate to house viewing.

It’s within the final 25 minutes of the movie that Carter actually digs into the meatier points and develops an sudden emotional gravity. There may be the query of kinship — the household we’re born into and the “household” we discover — and the way duties of duty and care determine into these relationships. The movie additionally raises questions on identification and the data battle by Carter’s lack of reminiscence. The pervasiveness of know-how — the movie takes this very actually, by the embedded electronics in Carter’s physique — reverberates with relevance. Simply as Carter grapples with attempting to determine his identification by the ceaseless inflow of textual content messages in addition to data given by a faceless voice, know-how has additionally disconcertingly turn into a serious drive in figuring out information about ourselves and the world.

These are all fascinating questions raised by Carter. Nonetheless, viewers could discover themselves having to dig nicely beneath the movie’s explosions and chase scenes to seek out them.

Carter is streaming on Netflix now.

Movie Reviews

‘Martha’ Review: R.J. Cutler Tries to Get Martha Stewart to Let Down Her Guard in Mixed-Bag Netflix Doc

From teenage model to upper-crust caterer to domestic doyenne to media-spanning billionaire to scapegoated convict to octogenarian thirst trap enthusiast and Snoop Dogg chum, Martha Stewart has had a life that defies belief, or at least congruity.

It’s an unlikely journey that has been carried out largely in the public eye, which gives R.J. Cutler a particular challenge with his new Netflix documentary, Martha. Maybe there are young viewers who don’t know what Martha Stewart‘s life was before she hosted dinner parties with Snoop. Perhaps there are older audiences who thought that after spending time at the prison misleadingly known as Camp Cupcake, Martha Stewart slunk off into embarrassed obscurity.

Martha

The Bottom Line Makes for an entertaining but evasive star subject.

Venue: Telluride Film Festival

Distributor: Netflix

Director: R.J. Cutler

1 hour 55 minutes

Those are probably the 115-minute documentary’s target audiences — people impressed enough to be interested in Martha Stewart, but not curious enough to have traced her course actively. It’s a very, very straightforward and linear documentary in which the actual revelations are limited more by your awareness than anything else.

In lieu of revelations, though, what keeps Martha engaging is watching Cutler thrust and parry with his subject. The prolific documentarian has done films on the likes of Anna Wintour and Dick Cheney, so he knows from prickly stars, and in Martha Stewart he has a heroine with enough power and well-earned don’t-give-a-f**k that she’ll only say exactly what she wants to say in the context that she wants to say it. Icy when she wants to be, selectively candid when it suits her purposes, Stewart makes Martha into almost a collaboration: half the story she wants to tell and half the degree to which Cutler buys that story. And the latter, much more than the completely bland biographical trappings and rote formal approach, is entertaining.

Cutler has pushed the spotlight exclusively onto Stewart. Although he’s conducted many new interviews for the documentary, with friends and co-workers and family and even a few adversaries, only Stewart gets the on-screen talking head treatment. Everybody else gets to give their feedback in audio-only conversations that have to take their place behind footage of Martha through the years, as well as the current access Stewart gave production to what seems to have been mostly her lavish Turkey Hill farmhouse.

Those “access” scenes, in which Stewart goes about her business without acknowledging the camera, illustrate her general approach to the documentary, which I could sum up as “I’m prepared to give you my time, but mostly as it’s convenient to me.”

At 83 and still busier than almost any human on the globe, Stewart needs this documentary less than the documentary needs her, and she absolutely knows it. Cutler tries to draw her out and includes himself pushing Stewart on certain points, like the difference between her husband’s affair, which still angers her, and her own contemporaneous infidelity. Whenever possible, Stewart tries to absent herself from being an active part of the stickier conversations by handing off correspondences and her diary from prison, letting Cutler do what he wants with those semi-revealing documents.

“Take it out of the letters,” she instructs him after the dead-ended chat about the end of her marriage, adding that she simply doesn’t revel in self-pity.

And Cutler tries, getting a voiceover actor to read those letters and diary entries and filling in visual gaps with unremarkable still illustrations.

Just as Stewart makes Cutler fill in certain gaps, the director makes viewers read between the lines frequently. In the back-and-forth about their affairs, he mentions speaking with Andy, her ex, but Andy is never heard in the documentary. Take it as you will. And take it as you will that she blames prducer Mark Burnett for not understanding her brand in her post-prison daytime show — which may or may not explain Burnett’s absence, as well as the decision to treat The Martha Stewart Show as a fleeting disaster (it actually ran 1,162 episodes over seven seasons) and to pretend that The Apprentice: Martha Stewart never existed. The gaps and exclusions are particularly visible in the post-prison part of her life, which can be summed up as, “Everything was bad and then she roasted Justin Bieber and everything was good.”

Occasionally, Stewart gives the impression that she’s let her protective veneer slip, like when she says of the New York Post reporter covering her trial: “She’s dead now, thank goodness. Nobody has to put up with that crap that she was writing.” But that’s not letting anything slip. It’s pure and calculated and utterly cutthroat. More frequently when Stewart wants to show contempt, she rolls her eyes or stares in Cutler’s direction waiting for him to move on. That’s evisceration enough.

Stewart isn’t a producer on Martha, and I’m sure there are things here she probably would have preferred not to bother with again at all. But at the same time, you can sense that either she’s steering the theme of the documentary or she’s giving Cutler what he needs for his own clear theme. Throughout the first half, her desire for perfection is mentioned over and over again and, by the end, she pauses and summarizes her life’s course with, “I think imperfection is something that you can deal with.”

Seeing her interact with Cutler and with her staff, there’s no indication that she has set aside her exacting standards. Instead, she’s found a calculatedly imperfect version of herself that people like, and she’s perfected that. It is, as she might put it, a good thing.

Movie Reviews

Reagan Is Almost Fun-Bad But It’s Mostly Just Bad-Bad

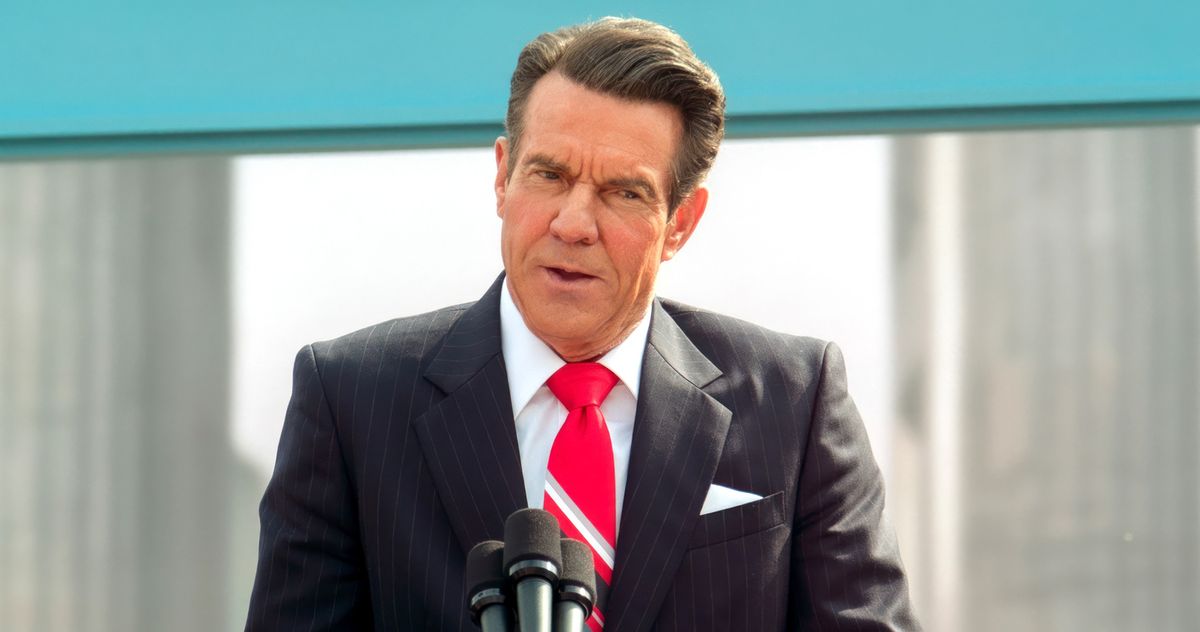

Dennis Quaid in Reagan.

Photo: Showbiz Direct/Everett Collection

Reagan is pure hagiography, but it’s not even one of those convincing hagiographies that pummel you into submission with compelling scenes that reinforce their subject’s greatness. Sean McNamara’s film has slick surfaces, but it’s so shallow and one-note that it actually does Ronald Reagan a disservice. The picture attempts to take in the full arc of the President’s life, following him from childhood right through to his 1994 announcement at the age of 83 that he’d been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s Disease. But you’d never guess that this man was at all complex, complicated, conflicted — in other words, human. He might as well be one of those animatronic robots at Disney World, mouthing lines from his famous speeches.

Dennis Quaid, a very good actor who can usually work hints of sadness into his manic machismo, is hamstrung here by the need to impersonate. He gets the voice down well (and he certainly says “Well” a lot) and he tries to do what he can with Reagan’s occasional political or career setbacks, but gone is that unpredictable glint in the actor’s eye. This Reagan doesn’t seem to have much of an interior life. Everything he thinks or feels, he says — which is maybe an admirable trait in a politician, but makes for boring art.

The film’s arc is wide and its focus is narrow. Reagan is mainly about its subject’s lifelong opposition to Communism, carrying him through his battles against labor organizers as president of the Screen Actors Guild and eventually to higher public office. The movie is narrated by a retired Soviet intelligence official (Jon Voight) in the present day, answering a younger counterpart’s questions about how the Russian empire was destroyed. He calls Reagan “the Crusader” and the moniker is meant to be both combative and respectful: He admires Reagan’s single-minded dedication to fighting the Soviets. They, after all, were single-minded in their dedication to fighting the U.S., and the agent has a ton of folders and films proving that the KGB had been watching Reagan for a long, long time.

By the way, you did read that correctly. Jon Voight plays a KGB officer in this picture, complete with a super-thick Russian accent. There’s a lot of dress-up going on — it’s like Basquiat for Republicans, even though the cast is certainly not all Republicans — and there’s some campy fun to be had here. Much has been made of Creed’s Scott Stapp doing a very flamboyant Frank Sinatra, though I regret to announce that he’s only onscreen for a few seconds. Robert Davi gets more screentime as Leonid Brezhnev, as does Kevin Dillon as Jack Warner. Xander Berkeley puts in fine work as George Schultz, and a game Mena Suvari shows up as an intriguingly pissy Jane Wyman, Reagan’s first wife. As Margaret Thatcher, Lesley-Anne Down gets to utter an orgasmic “Well done, cowboy!” when she sees Reagan’s “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall” speech on TV. And my ’80s-kid brain is still processing C. Thomas Howell being cast as Caspar Weinberger.

To be fair, a lot of historians give Reagan credit for helping bring about both the Gorbachev revolution and the eventual downfall of the U.S.S.R. and its satellites, so the film’s focus is not in and of itself a misguided one. There are stories to be told within that scope — interesting ones, controversial ones, the kind that could get audiences talking and arguing, and even ones that could help breathe life into the moribund state of conservative filmmaking. But without any lifelike characters, it’s hard to find oneself caring, and thus, Reagan’s dedication to such narrow themes proves limiting. We get little mention of his family life (aside from his non-stop devotion to Nancy, played by Penelope Ann Miller, and vice versa). Other issues of the day are breezed through with a couple of quick montages. All of this could have given some texture to the story and lent dimensionality to such an enormously consequential figure. But then again, if the only character flaw you could find in Ronald Reagan was that he was too honest, then maybe you weren’t very serious about depicting him as a human being to begin with.

See All

Movie Reviews

‘Don’t Let’s Go to the Dogs Tonight’ Review: An Extraordinary Adaptation Takes a Child’s-Eye View of an African Civil War

Alexandra Fuller‘s bestselling 2001 memoir of growing up in Africa is so cinematic, full of personal drama and political upheaval against a vivid landscape, that it’s a wonder it hasn’t been turned into a film before. But it was worth waiting for Embeth Davidtz’s eloquent adaptation, which depicts a child’s-eye view of the civil war that created the country of Zimbabwe, formerly Rhodesia — a change the girl’s white colonial parents fiercely resisted.

Davidtz, known as an actress (Schindler’s List, among many others), directs and wrote the screenplay for Don’t Let’s Go to the Dogs Tonight and stars as Fuller’s sad, alcoholic mother. Or, actually, co-stars, because the entire movie rests on the tiny shoulders and remarkably lifelike performance of Lexi Venter — just 7 when the picture, her first, was shot. It is a bold risk to put so much weight on a child’s work, but like so many of Davidtz’s choices here, it also turns out to be shrewd.

Don’t Let’s Go to the Dogs Tonight

The Bottom Line Near perfection.

Venue: Telluride Film Festival

Cast: Lexi Venter, Embeth Davidtz, Zikhona Bali, Fumani N Shilubana, Rob Van Vuuren, Anina Hope Reed

Director-screenwriter: Embeth Davidtz

1 hour 38 minutes

Another those smart calls is to focus intensely on one period of Fuller’s childhood. Don’t Let’s Go to the Dogs Tonight is set in 1980, just before and during the election that would bring the country’s Black majority to power. Bobo, as Fuller was called, is a raggedy kid with a perpetually dirty face and uncombed hair, who’s seen at times riding a motorbike or sneaking cigarettes. She runs around the family farm, whose run-down look and dusty ground tell of a hardscrabble existence. The film was shot in South Africa, and Willie Nel’s cinematography, with glaring bright light, suggests the scorching feel of the sun.

Much of the story is told in Bobo’s voiceover, in Venter’s completely natural delivery, and in another daring and effective choice, all of it is told from her point of view. Davidtz’s screenplay deftly lets us hear and see the racism that surrounds the child, and the ideas that she has innocently taken in from her parents. And we recognize the emotional cost of the war, even when Bobo doesn’t. She often mentions terrorists, saying she is afraid to go into the bathroom alone at night in case there’s one waiting for her “with a knife or a gun or a spear.” She keeps an eye out for them while riding into town in the family car with an armed convoy. “Africans turned into terrorists and that’s how the war started,” she explains, parroting what she has heard.

At one point, the convoy glides past an affluent white neighborhood. That glimpse helps Davidtz situate the Fullers, putting their assumptions of privilege into context. Bobo has absorbed those notions without quite losing her innocence. Referring to the family’s servants, her voiceover says that Sarah (Zikhona Bali) and Jacob (Fumani N. Shilubana) live on the farm, and that “Africans don’t have last names.” Bobo adores Sarah and the stories she tells from her own culture, but Bobo also feels that she can boss Sarah around.

Venter is astonishing throughout. In close-up, she looks wide-eyed and aghast when visiting her grandfather, who has apparently had a stroke. At another point, she says of her mother, “Mum says she’d trade all of us for a horse and her dogs.” When she says, after the briefest pause, “But I know that’s not true,” her tone is not one of defiant disbelief or childlike belief, as might have been expected. It’s more nuanced, with a hint of sadness that suggests a realization just beyond her young grasp. Davidtz surely had a lot to do with that, and her editor, Nicholas Contaras, has cut all Bobo’s scenes into a sharply perfect length. Nonetheless, Venter’s work here brings to mind Anna Paquin, who won an Oscar as a child for her thoroughly believable role as a girl also who sees more than she knows in The Piano.

The largely South African cast displays the same naturalism as Venter, creating a consistent tone. Rob Van Vuuren plays Bobo’s father, who is at times away fighting, and Anina Hope Reed is her older sister. Bali and Shilubana are especially impressive as Sarah and Jacob, their portrayals suggesting a resistance to white rule that the characters can’t always speak out loud.

Davidtz has a showier role as Nicola Fuller. (The movie doesn’t explain its title, which hails from the early 20th century writer A.P Herbert’s line, “Don’t let’s go the dogs tonight, for mother will be there.”) Once, Nicola shoots a snake in the kitchen and calmly wanders off, ordering Jacob to bring her tea. More often, Bobo watches her mother drift around the house or sit on the porch in an alcoholic fog. But when her voiceover tells us about the little sister who drowned, we fathom the grief behind Nicola’s depression. And wrong-headed though she is, we understand her fury and distress when the election results make her feel that she is about to lose the country she thinks of as home. Davidtz gives herself a scene at a neighborhood dance that goes on a bit too long, but it’s the rare sequence that does.

There is more of Fuller’s memoir that might be a source for other adaptations. It is hard to imagine any would be more beautifully realized than this.

-

Connecticut1 week ago

Connecticut1 week agoOxford church provides sanctuary during Sunday's damaging storm

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoBreakthrough robo-glove gives you superhuman grip

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week ago2024 showdown: What happens next in the Kamala Harris-Donald Trump face-off

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoWho Are Kamala Harris’s 1.5 Million New Donors?

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoTrump taunted over speculated RFK Jr endorsement: 'Weird as hell'

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoVivek Ramaswamy sounds off on potential RFK Jr. role in a Trump administration

-

World6 days ago

World6 days agoPortugal coast hit by 5.3 magnitude earthquake

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoHouse GOP demands elite universities counteract 'dangerous' anti-Israel protests in the fall semester