Movie Reviews

Film Review: Falling in Love Like in Movies (2023) by Yandy Laurens

“I can’t do retakes in my life”

The intense emergence of films about films that has been happening the last few years in Asian cinema is probably one of the most exciting concepts to be taking place in the region’s cinema. Yandy Laurens tries his hand in the (sub) genre, through an approach that provides one of its apogees.

The film shows its colors (pun intended) from the introductory scene. A script writer, Bagus (who is played by Ringgo Agus Rahman) enters the office of his producer, Yoram, who, once more, wants him to adapt another successful TV drama to a movie. Bagus, however, has another concept in his mind, of a black-and-white rom-com which is based on his actual experience, after meeting Hana, his old high school flames, and pursues a romantic relationship with her, even though it has just been 4 months since her husband died. As soon as he mentions black-and-white, the frame and the color of the movie change to suit his words, and the narrative changes to his actual experiences. Since the producer agrees, though, the shooting of the film actually becomes part of the narrative, which has it moving within and outside the film creating various meta levels, in a way that can only be compared with “One Cut of the Dead”, although in completely different, rom-com prism this time.

Yandy Laurens shoots a very ambitious project, with the aforementioned, meta-layer approach being quite difficult to implement in theory, but he manages to pass the ‘test’ with flying colors. The way the story moves inside and outside the movie is impressive, while allowing him to make a number of quite realistic comments, both regarding the shooting of movies and how the industry works in Indonesia. Regarding the latter, the discussions with the producer are rather indicative. Bagus wants to make an artistic black-and-white rom-com following the 8 chapter “rule” of the genre (which he also actually does in the actual movie). Yoram, on the other hand, having commercial success in his mind, wants him either to adapt a TV drama, or if the script is original, to at least be a horror. Another solution comes from having big names in it, either in the director’s seat (with the name of Riri Riza coming up) or in the cast. Lastly, the final solution if nothing else works, is to make the movie fast with the least possible cost, in a comment that essentially applies to the whole independent movie industry.

Furthermore, that two of the protagonists in the movie, Cheline and Dion (you get it, right?), a married couple who are Bagus’s best friends, are the editor and the main actor of his movie, allows Laurens to present how films work, both during the shoot and around it. The appearance of Julie Estelle as essentially herself adds to both this element, and the meta one we described just before, with the same applying with Dion Wiyoko who plays Dion.

This whole aspect, however, finds its apogee in the ‘racing scene” where an impressive Sheila Dara Aisha as Cheline dictates how the movie should look in the scene, with what we are seeing on the screen actually following her words. The drone shot that moves around and back to the bike she along with Dion and Bagus are riding is probably the most impressive in the whole movie, as is actually the whole sequence, where, additionally, Dimas Bagus Triatma Yoga’s cinematography and Hendra Adhi Susanto’s editing find their zenith.

The presence of the also excellent Nirina Zubir as Hana, on the other hand, and her interactions with Bagus, allow for more character analysis and a series of social comments having to do with relationships, essentially adding yet another level to the movie. The concept of grief and the possibility of finding true love at a later age in life is the most obvious one, but Laurens also talks about how people can become rather self-centered with their feelings, ignoring those of others in the process. That the one in fault here is Bagus could be perceived as a comment regarding artists and how focused (in a negative way) can become with their art, with the way his interactions proceed with Hana essentially maturing him as the movie progresses. At the same time, the value of communication and being truthful is highlighted too, adding even more to the rather rich narrative here. Lastly, that cinema can imitate life, but it is not the same as living and experiencing it, emerges as one of the most smart and accurate remarks Laurens makes.

Check also this interview

Through the aforementioned, the performance by Ringgo Agus Rahman also emerges as excellent, with his interactions with the rest of the protagonists, showcasing, additionally, the outstanding chemistry between them.

The film can be a bit too dialogue-heavy on occasion, and would definitely benefit from a tighter ending, but these are just minor issues here, with “Falling in Love Like in Movies” emerging as a film that is rather smart and intelligent, rather fun, rather informative, and rather entertaining in equal measures.

Movie Reviews

‘Apartment 7A’ Review: Julia Garner and Dianne Wiest Star in Paramount+’s Oddly Lethargic Companion to ‘Rosemary’s Baby’

Soon after Rosemary (Mia Farrow), the protagonist of 1968’s Rosemary’s Baby, moves into the stately Renaissance revival building known as the Bramford with her husband, she meets Terry Gionoffri. Their encounter is brief but impactful.

Terry, portrayed with infectious ebullience by Victoria Vetri, eases Rosemary’s nerves about her recent move, reassuring her that the New York apartment’s other occupants are kind. In turn, Rosemary offers Terry a hopeful companionship. The two promise to make their laundry trips together as neither can stand the spooky basement. Before they part ways, Terry tells Rosemary about the Castevets, an older couple who helped her during a rough season. “I’d be dead now if it wasn’t for them,” Terry says, “that’s an absolute fact.”

Apartment 7A

The Bottom Line Doesn’t inspire enough creeping dread or jumpy frights.

Release date: Friday, Sept. 27 (Paramount+)

Cast: Julia Garner, Dianne Wiest, Jim Sturgess, Kevin McNally Andrew Buchan, Marli Siu

Director: Natalie Erika James

Screenwriters: Natalie Erika James, Christian White, Skylar James

Rated R,

1 hour 44 minutes

Paramount+’s Apartment 7A, directed by Natalie Erika James (Relic), uses Terry to introduce a new generation of viewers to that terrifying universe of Satanic cults and maternal purgatory first conjured by author Ira Levin and further popularized by Roman Polanski’s intense cinematic adaptation. James, who co-wrote the screenplay with Christian White and Skylar James, fills out Terry’s biography to explain her tragic fate and strengthen the connection between her and Rosemary. It’s not so much a prequel as it is a parallel story that continues underscoring the limited autonomy of women. Restrictive social mores trap both Rosemary and Terry, albeit in different ways.

Whereas Rosemary is married and toys with the idea of having a child, Terry is a single woman trying to be a Broadway star. Apartment 7A opens with Terry (Julia Garner) preparing for her theater debut in a backstage dressing room. Excitement flashes across her eyes as the ingénue practices vocal warmups and puts finishing touches on her makeup. The glimmer dims when Terry later injures herself on stage. Unable to dance, she self-medicates with pills bought from a local busker and develops an addiction to painkillers. James portrays Terry’s descent into dependency with a laconic efficiency, which initially serves the narrative’s slow-burn pace.

Without a job, Terry relies on her friend Annie (Marli Siu) for support. Another rejection catapults the hurt performer into a deeper depression. Terry becomes so desperate that she follows Alan Marchand (Jim Sturgess), the producer of her most recent audition, to his home at the Bramford, hoping to convince him to give her another chance. But the doorman dismisses Terry at the front desk, and minutes later, she collapses on the sidewalk outside.

The plot picks up when Minnie (an excellent Dianne Wiest) and Roman Castevet (Kevin McNally) rescue Terry. But the tone stays oddly mellow, not quite inspiring the creeping dread of Polanksi’s adaptation, nor the jumpy fright often abused by contemporary horror offerings. Partial blame might lie in the attempts to reconcile Terry’s reality and her star aspirations. James includes a number of musical sequences, usually when Terry is between a waking and sleeping state. But these fever dreams land more as campy interruptions than as surreal and heightened hauntings. They also strip the subtlety out of Apartment 7A’s more understated messaging.

The film is desperate for audiences to understand that in accepting the Castevets’ generosity, Terry has assumed the role of a lifetime. Details of this position become clearer after the dancer moves into the vacant unit next to the older couple. They begin to manage Terry’s life so that she eventually lands a role in a big play and worries less about money. But anything “free” has a tradeoff. Morning sickness tips Terry off to her pregnancy and a visit to a health clinic confirms it. Before Rosemary carried the son of the antichrist, Terry did. Apartment 7A doesn’t investigate that fateful encounter between the two women in Rosemary’s Baby, but their interaction lives in the shadows, serving as a reminder of the Bramford residents’ depravity.

Inheriting the role from Vetri, Ozark star Garner imbues the bubbly Terry with darker undertones. She finds some complexity in her ambition, which drives the character farther into the arms of the Castevets. There’s an assured effort on Garner’s part to do more with the part, but a distance remains between the audience and Terry.

Wiest gets closer to narrowing that gap with her character. She modulates her performance so that Minnie’s personality shifts slowly from an overbearing warmth to an abrasive insistence. One of the strongest scenes sees Minnie, while giving Terry a haircut, communicate that the dancer will never be cleverer than she is. Aside from the final scene, Garner and Wiest are at their best in this nail-bitingly intense moment. As Minnie’s grip tightens on Terry’s hair, the terms of their agreement become devastatingly clear: a baby in exchange for fame.

Through Terry’s pregnancy, the movie, similar to Rosemary’s Baby, underscores the themes of bodily autonomy. James’ film is particularly compelling in post-Roe America, when recent headlines about punitive laws barring abortion access have lent it an urgent political valence, so it’s a shame that its energy doesn’t always match its relevance. Conversations between Annie and Terry heighten the stakes, as does the increasingly hostile relationship between Terry and Minnie, but most of Apartment 7A feels too mellow for its messages.

Movie Reviews

Super/Man: The Christopher Reeve Story movie review (2024) | Roger Ebert

On May 27, 1995, Christopher Reeve, who became internationally famous playing the title character in the original Superman movies, was riding at the Commonwealth Park equestrian center in Culpeper, Virginia when his horse refused to jump a one meter tall, W-shaped fence. Reeve fell and shattered his top two vertebrae. He barely survived, was rendered quadriplegic and nearly immobile, and would endure severe breathing challenges for the rest of his life. Headlines around the world treated this as a great irony: Superman not only couldn’t fly anymore, he could barely move. It was an understandable way to frame it, but and well-meaning, but ultimately dehumanizing.

The new documentary “Super/Man: The Christopher Reeve Story” pushes back against that presentation of Reeve’s accident and does their best not to treat Reeve’s story as that of a man who had it all but suddenly lost it. Instead, Reeve’s life is presented as a story of nearly superhuman endurance and determination: a beautiful and athletic movie star was struck down in his prime, then reconfigured himself as activist on behalf of people with disabilities, as well as a champion of funding for science that might alleviate or eliminate the suffering of others with spinal cord injuries.

Co-directed by Ian Bonhôte and Peter Ettedgui, “Super/Man” doesn’t flinch from the blunt physical facts of what happened. But in the end the approach cements the movie as a work of integrity. It consistently refuses to walk the much easier path taken by previous accounts of Reeve’s life, which front-loaded the story with his rise to stardom and attempts to move beyond his defining role as Superman, then presented his life after the accident as an inspiring postscript that couldn’t be lingered over because it would make audiences sad.

The filmmakers here aren’t sugarcoating anything here. They’re laying out what happened: not just the basic facts of Reeve’s life before and after, but the emotional impact on his friends (including his Juilliard acting program roommate Robin Williams, who was like a brother to him); his wife Dana, a super-heroic spouse who took care of him, and inspired and joined his activism; his first two children, Matthew and Alexandra; the kids’ mother Gae Exton (Reeve’s on-again, off-again girlfriend for a decade); and most piercingly, little Will Reeve, his son with Dana. Will was a toddler when the accident happened, and spent his third birthday without his father because Reeve was in the hospital fighting for his life. There are a lot of moving home video snippets in the documentary, but the bits showing that beautiful little boy, who was then too young to understand the magnitude of his father’s suffering, are right up at the top.

There’s a fair amount of information about Reeve’s career as an actor, especially his struggle to reconcile his beloved performance as Superman against his desire to prove himself in other types of roles (which he did in “Street Smart,” “Deathtrap” and “Somewhere in Time,” even though audiences didn’t turn out like they did when he wore the cape and tights). But this aspect of his life is interspersed with the account of his accident, survival, and subsequent attempts to manage his pain, relearn everything about how to live, and become a spokesperson for others dealing with the same challenges.

The movie feels a bit rushed or compacted at times—sometimes you might want it to live inside of a moment for longer than it does—and the music, which seems to be aiming for effects comparable to John Williams’ “Superman” score, is too ever-present, intrusive and loud at times; it often seems to be trying to tell us how to feel, which just isn’t necessary with a story so inherently harrowing and inspiring.

But all in all, this is a thoughtful and at times remarkable piece of nonfiction, working in an accessible commercial vein but doing its best not to take the easy way into any aspect of Reeve’s story. It’s most impressive when it’s pointing a camera at Reeve’s colleagues (including Glenn Close, Jeff Daniels and Whoopi Goldberg) as they talk about Reeve’s attempts to reinvent himself as a visibly paralyzed actor (he did a made-for-TV remake of “Rear Window”) and as a director, and even more so, when it’s letting his children tell the story of their father’s perseverance and the dedication of Dana Reeve, who is presented as so single-mindedly devoted to his physical and emotional care that you can understand why she wasn’t around for very long after her husband’s passing in 2004. Documentaries that really know how to listen are increasingly rare, and this is a good one.

The movie deserves a wide audience, and hopefully will redouble efforts to search for medical solutions that can ease the suffering of people with spinal cord injuries or perhaps one day make them a thing of the past.

Movie Reviews

Yudhra Movie Review: Cutting-edge action salvages this meandering crime drama

Review: Siddhant Chaturvedi (as Yudhra) amps up his inner MC Sher to portray a hothead battling daddy issues and strange love for lizards. He gets triggered at the drop of a hat but has his heart in the right place. As an out-and-out mercurial action hero, he pulls off the angry young man with a twist convincingly despite his innocent baby face. He may not look menacing but packs a punch.

Yudhra finds ruthless adversaries in drug lord Firoz (Raj Arjun) and his son Shafiq (Raghav Juyal). The former hams a bit but Raghav has quickly emerged as one of the most interesting antagonists in recent times. On the heels of violent action thriller ‘Kill’ comes yet another striking performance from the dancer-turned-actor who knows how to play the freak. Ram Kapoor plays a suspicious cop and Gajraj Rao, Yudhra’s father.

The cutting-edge action serves as the film’s backbone and its biggest asset. The music store sequence featuring Malavika, Siddhant and Raghav is one of the finest action scenes in a Bollywood movie. The bicycle parkour scene is nerve-racking too. Action director Nick Powell, known for his work in Gladiator, has worked on the movie and the action choreography keeps you on tenterhooks for a reason. It is intense, gripping and integral to storytelling. The film is technically sound. You appreciate the neurotic world building and the unique background score, but the story lacks emotional heft.

Though the posters may mislead you into believing that this is an old school crime drama (belonging to the Vaastav era), Yudhra is far from that. It is contemporary in nature. You wish it had the compelling structure of its predecessors where the angry young man had a cause to rebel. Even with aimless anger, a film can find its footing and Yudhra shows ample promise but doesn’t quite capitalize on its intentional sankiness (insanity). The first half builds momentum and creates an anticipation of a solid twist, but the second half douses its own fire before things could get all heated. The film never reaches the tipping point despite showing promise and that’s frustrating.

Director Ravi Udyawar uses action and violence as cinematic language to give you that rage room effect. The style and stunts are on point, but the story meanders. Characters are skillfully created, and their swagger ensures there’s not a single dull moment. Siddhant and Malavika look great but lack the chemistry required to establish their connect.

Be it Bloody Daddy, Kill and now Yudhra. It’s interesting to see Bollywood going full throttle in action. But action doesn’t need to be devoid of emotions.

-

Movie Reviews1 week ago

Movie Reviews1 week ago‘Saturday Night’ review: A madcap backstage ode to Lorne Michaels’ legendary show

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoVideo: What Taylor Swift’s Endorsement Means for Kamala Harris

-

Movie Reviews1 week ago

Movie Reviews1 week agoIs a Movie About Electing a Pope Allowed to Be This Entertaining?

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoWhat bombs did Israel use against the al-Mawasi ‘safe zone’ in Gaza?

-

Politics1 week ago

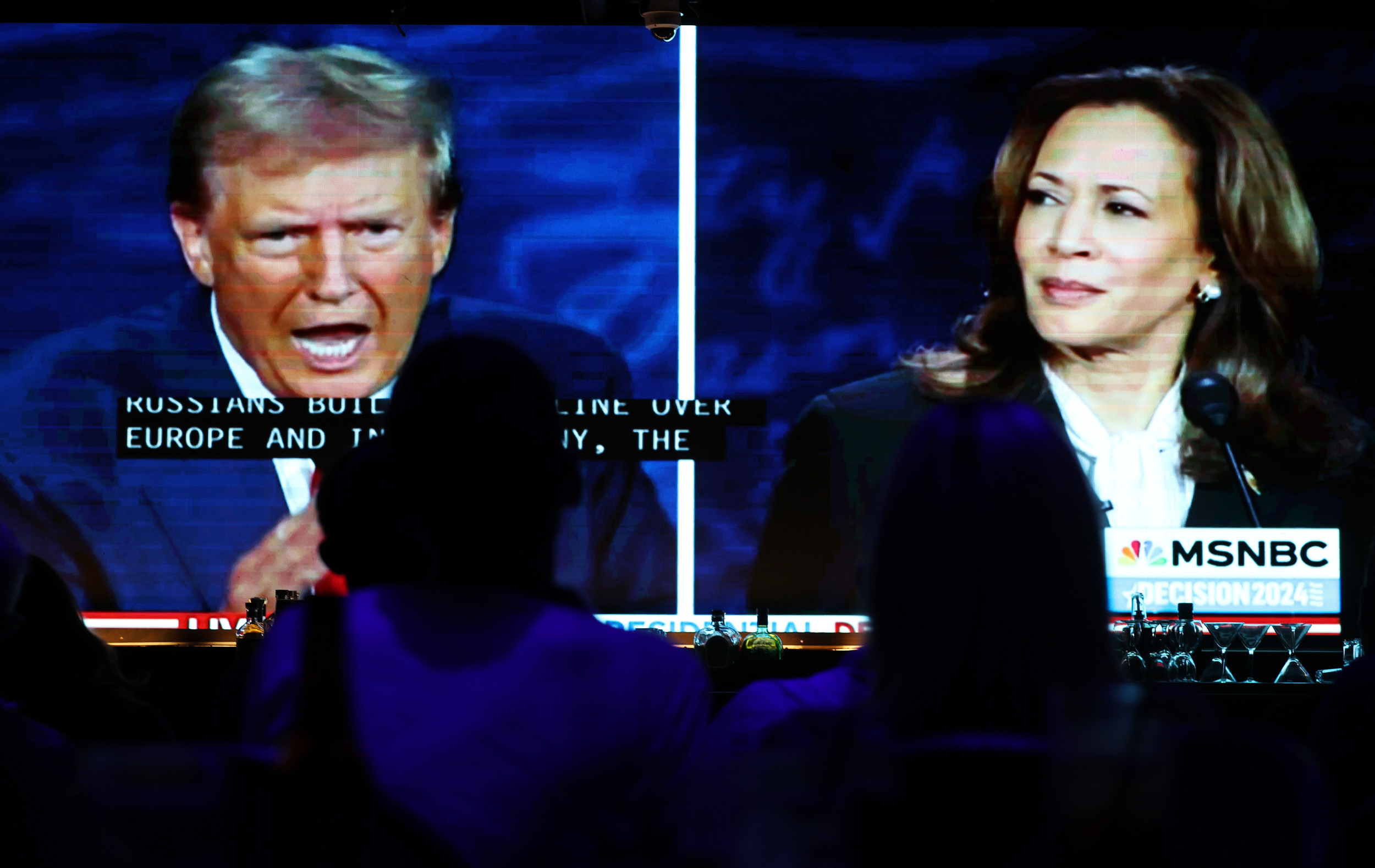

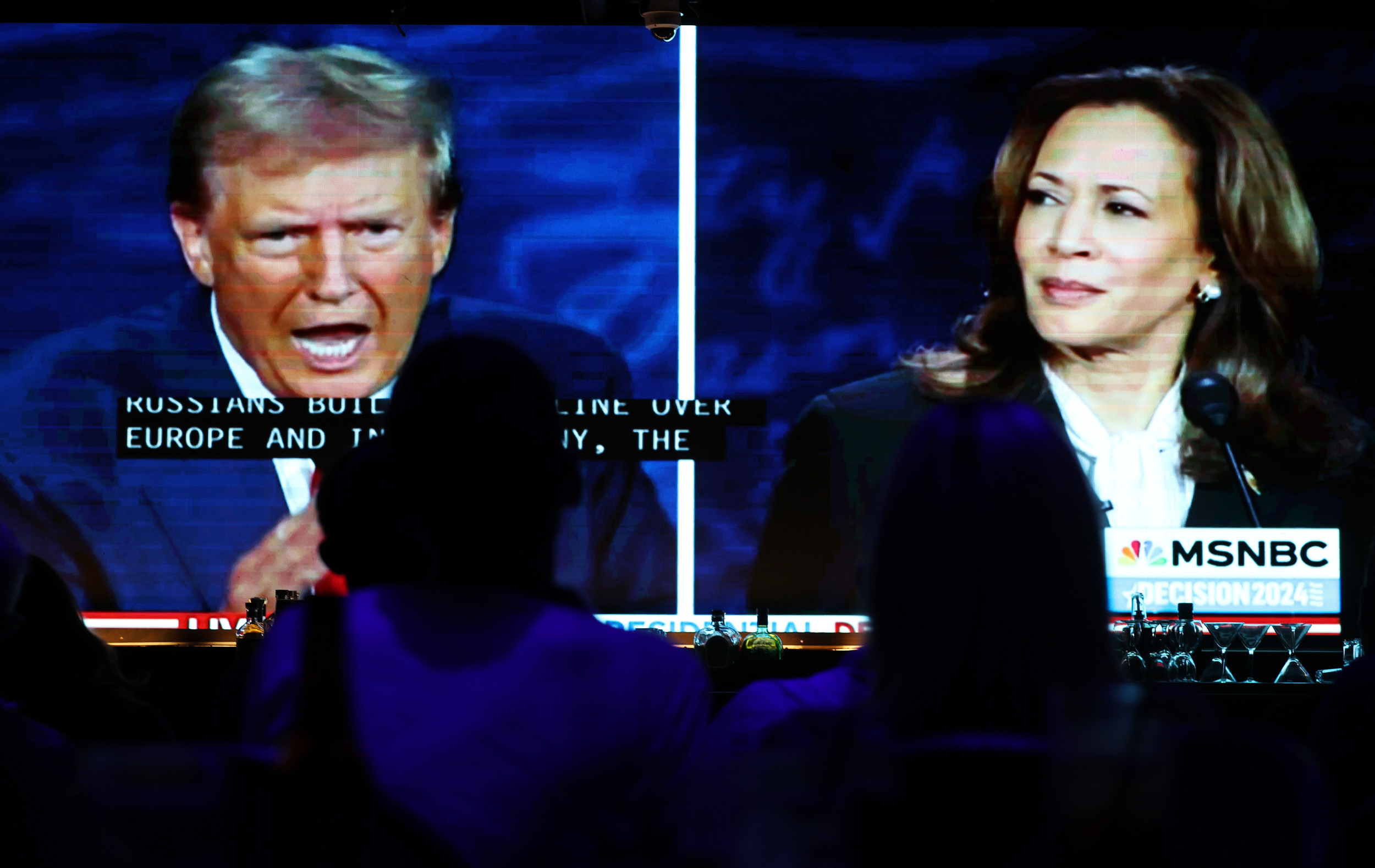

Politics1 week agoDemocrats heap praise on Harris' debate performance, say she 'destroyed' Trump's career

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoTrump and Harris’ first showdown attracts more viewers than Biden debate

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoVideo: Trump and Harris Clash in a Fiery Presidential Debate

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoDem congressman says Trump should talk about dropping out after debate