Movie Reviews

‘Alex’s War’ Review: A Gripping and Disturbing Look at Alex Jones and the Politics of Unreality

In the beginning of “Alex’s Battle,” a documentary about Alex Jones, the notorious talk-news conspiracist guru of InfoWars is described by assorted media shops as “a efficiency artist,” “paranoia porn,” and — within the phrases of John Oliver — “the Walter Cronkite of shrieking bat-shit guerrilla clowns.” All of which, after all, is correct. But none of it absolutely captures what an necessary determine Alex Jones has develop into, whilst he’s been systematically deplatformed. (The deplatforming, after all, solely helped his trigger. It shored up and even mythologized his picture as The Man Talking Fact to the Energy That Doesn’t Need You to Hear Him.)

A few a long time in the past, when he was on the rise because the ranting scourge of “globalism” and different evils, most of us dismissed Alex Jones as an outlier and a self-promoting blowhard who was finally a trivial voice shouting from the wilderness of his excessive beliefs. There was no denying that he had the charisma of a right-wing fire-breather like Michael Savage. However the defining high quality of Alex Jones was a willingness — greater than that, a compulsion — to lend credibility to conspiratorial nonsense. The Oklahoma Metropolis bombing was, he mentioned, an inside job, introduced off with the cooperation of the U.S. authorities; so was 9/11. These beliefs, or so it appeared on the time, have been on the perimeter of the perimeter.

Because it turned out, although, Alex Jones, along with his raving fruitcake paranoia, was an avatar of the brand new age. He has remained, in some horrible method, constant in his beliefs, all the time blaming the federal government — and, by extension, the globalist cabal — for no matter catastrophe befalls us. The assertion, which he clung to for years, that the Sandy Hook Elementary Faculty bloodbath was staged, one other hologram within the authorities’s grand plan to regulate us, could have sounded, on the face of it, like the assumption of somebody who was dropping his psychological schools. But how a lot of a leap is it from that stage of warped actuality to the trope that Jones grew to become head cheerleader on two years in the past: that Joe Biden stole the election? And that’s a perception that has taken over the Republican Occasion, to not point out a superb slice of the American voters. Whereas Alex Jones was, and is, a bat-shit guerrilla clown, the reality is that to a disturbing diploma it’s now his world, and we simply stay in it.

“Alex’s Battle” is a film that helps us perceive how that occurred. Directed and edited by Alex Lee Moyer, it’s a somewhat unusual movie, in that it’s two hours and 11 minutes lengthy, and for that total time we’re immersed on the planet in line with Alex Jones with out something in the way in which of meditating voices. To name the movie uncritical can be an understatement. It presents, with out commentary, a documentary file of Jones’ profession, from his earliest days on public-access TV to his rise as a talk-radio maven to his standing as a rabble-rouser of rebellion, a person who was instrumental in stoking the trend that fueled the chaos and destruction of January 6. Moyer acquired unbelievable entry to Jones, however you possibly can argue that to take action she allowed her film to fall down in its function. “Alex’s Battle” by no means overtly takes Jones to job. It by no means frames his celeb as half of a bigger social virus of darkish fantasy and misinformation. It doesn’t present you a factor about his private life, or something about his enterprise of utilizing politics to promote well being dietary supplements. “Alex’s Battle” is so freed from judgment that an Alex Jones fan might most likely watch it and assume, “He slays!”

So how might this be a accountable film? Within the following method. “Alex’s Battle” shouldn’t be a bit of pro-Jones propaganda. It’s nearer to a bit of media-age vérité that assumes we all know what the information are, and that we don’t have to have our palms held as Jones spews forth his red-pill view of actuality. Nonetheless, one may ask: Doesn’t this impartial perspective create a hazard of creating Jones look extra cheap and compelling than he’s? I’d argue that that’s the movie’s power. Alex Jones is a compelling determine — to thousands and thousands of his followers. He’s not simply an alt-right speak host you may disagree with; he’s a cult chief, the way in which Donald Trump is. In each circumstances, should you don’t grasp the elemental attraction of that, you’re simply holding your head within the sand.

Jones now appears like a retired pro-football lineman or an growing older biker, with a brawler’s construct and a beard grown to offset his thinning locks. We see him main protest marches in Washington, D.C., and Atlanta, the place he helped the “Cease the Steal” motion take root. As he stalks the streets shouting hoarsely by means of a bullhorn, he has a commandingly world-weary bruiser-of-the-people, freedom-fighter-as-martyr vibe. At 48, he carries himself like a rock star of the dispossessed. In the event that they made a biopic about Jones (and they need to), the actor to play him can be Russell Crowe.

However “Alex’s Battle” additionally options an excessive amount of archival footage of Jones in his earlier days, and these things is fascinating, since you see how he developed, and in addition how far forward of the curve of the brand new down-the-rabbit-hole America he was. Born in 1974, he grew up in Rockwall, a rich small city on the outskirts of Dallas, the place he was an athlete, a road fighter, and a delinquent. His household moved to Austin (to get him away from the powerful vibe of Dallas), and he has resided in that liberal bastion ever since. As a youngster, Jones could have been a punk, however he was additionally a voracious reader, consuming comedian books and science fiction and large fats tomes about historical past and fascism, in addition to “Julius Caesar” and Gary Allen’s “None Dare Name It Conspiracy,” which the movie quotes from: “In politics, nothing occurs accidentally. If it occurs, you may guess it was deliberate that method.” (It might be arduous to consider a press release offered because the holy fact that’s so fallacious.)

Throughout this era, buddies of Jones’ household included a U.S. operative who would discuss clandestine missions, in addition to somebody concerned within the authorities’s secret analysis on psychedelics. You assume: Truthful sufficient. However then Jones says, “My dad had buddies who have been within the John Birch Society, so there was a background noise from them in regards to the one-world authorities, the cashless society, the plan to interrupt up the household, and all this.”

That’s an astonishing quote, because it contains most of Jones’s shibboleths. Jones is all the time speaking in regards to the “analysis” he does (that phrase is a tic with him, as if he have been the Woodward and Bernstein of uncovering the New World Order). However what that quote reveals is that he swallowed most of his ideology whole-hog as an adolescent straight from the John Birch Society, a membership of anti-Communist, anti-Semitic late-’50s cranks who have been marginalized out of the conservative motion by William F. Buckley. You solely want a few quick strains to attach the dots from “The Protocols of the Elders of Zion” to the Birchers to Jones. That’s his analysis.

Within the ’90s, when he was nonetheless younger (he turned 20 in 1994), Jones was strikingly handsome in a Hollywood method. Along with his blond hair and regal smirk, he resembled a sunny-jock model of Bruce Davison, with a contact of a misplaced Bridges brother. He was a pure digital camera object, and speaking into the digital camera he felt proper at house. He had a cash stare: tight-lipped, thousand-yard, with unbreakable eye contact. From the beginning, he was a dystopian fabulist, which grew to become his type of showbiz. We see him on the website of the Oklahoma Metropolis bombing, sowing the seeds of conspiracy — which, as he now realized, you possibly can do with something. “Why has the media ignored two seismograph stories from the College of Oklahoma that present two distinct explosion patterns?” he asks. “I’m not sitting right here claiming to have the solutions, however I do know this: They don’t need you to know one thing. They’re holding one thing from you.” Welcome to the brand new fact!

But it wasn’t all conspiracy. Jones was like a preacher, and what he was preaching was a faith — “cease the dehumanization.” And actually, who doesn’t assume modern America is dehumanized and solely rising extra so? Who doesn’t really feel at occasions, on this society, overly managed — by expertise, by the corporatization that guidelines the expertise, by the federal government that works hand in glove with the firms, by not one however two political events that appear more and more out-of-touch with the wants of common individuals? Jones, like Trump, tapped into all that. However what gave it that means was the way in which that Jones, a political carny barker, used conspiracy to reverse-engineer historical past. To him, each catastrophe, each predicament, every little thing about our world you don’t like had been deliberate and prompted. By whom? By them. The globalists. The pedophiles. The technocrat corporatists who need to use vaccines to sterilize the inhabitants.

Jones had an interface with conventional media — and constructed his legend — when the BBC filmmaker Jon Ronson recruited him to infiltrate the Bohemian Grove, the annual two-week gathering of the wealthy and highly effective on a 2,700-acre campground in Monte Rio, Calif. He and his cameraman, Mike Hanson, snuck in by pretending to be fat-cat members of the elite, and as soon as there they filmed a Bohemian Grove ceremony, “Cremation of the Care,” throughout which the members put on costumes and cremate a coffin effigy earlier than a 40-foot owl. Jones’ interpretation of this — that the lads have been doing it to expiate their sins — was sheer conjecture, however there’s little question that when this footage was proven as a part of the BBC’s “Secret Rulers of the World,” it regarded like one thing out of “Eyes Extensive Shut.” It grew to become the cornerstone of Jones’ “proof” that the world was being overtaken by a cabal of globalist creeps.

But Jones, by his personal admission, finds many of the proof he seeks inside himself. We see his broadcasts on Sandy Hook, the place he mentioned issues like, “My intestine tells me individuals controlling the federal government have been concerned with this. And it’s not even the intestine, it’s the center. It’s proper right here in my coronary heart: I do know issues, I really feel issues.” Ah, analysis! The obscenity of the Sandy Hook rants, through which he claimed that the bloodbath was “a large hoax,” have been a paranoid wrinkle too far. The mother and father of the Sandy Hook victims filed a defamation swimsuit (they’re searching for $150 million in damages), and on account of that lawsuit it was reported solely at the moment that the mother or father firm of InfoWars has now filed for chapter. We see clips of Jones in a deposition, doing the worst form of dissembling — apologizing for what he mentioned, however not likely. Not denying the denial of actuality. He has develop into the Olympic champion of fake-news doublethink. However the different champion of that’s Donald Trump, who we see asking the gang on January 6, “Does anyone consider that Joe had 80 million votes?” He’s utilizing Jones’s Sandy Hook logic. I really feel it, so it have to be true. Overlook the globalists. That is the New World Order.

Movie Reviews

‘Martha’ Review: R.J. Cutler Tries to Get Martha Stewart to Let Down Her Guard in Mixed-Bag Netflix Doc

From teenage model to upper-crust caterer to domestic doyenne to media-spanning billionaire to scapegoated convict to octogenarian thirst trap enthusiast and Snoop Dogg chum, Martha Stewart has had a life that defies belief, or at least congruity.

It’s an unlikely journey that has been carried out largely in the public eye, which gives R.J. Cutler a particular challenge with his new Netflix documentary, Martha. Maybe there are young viewers who don’t know what Martha Stewart‘s life was before she hosted dinner parties with Snoop. Perhaps there are older audiences who thought that after spending time at the prison misleadingly known as Camp Cupcake, Martha Stewart slunk off into embarrassed obscurity.

Martha

The Bottom Line Makes for an entertaining but evasive star subject.

Venue: Telluride Film Festival

Distributor: Netflix

Director: R.J. Cutler

1 hour 55 minutes

Those are probably the 115-minute documentary’s target audiences — people impressed enough to be interested in Martha Stewart, but not curious enough to have traced her course actively. It’s a very, very straightforward and linear documentary in which the actual revelations are limited more by your awareness than anything else.

In lieu of revelations, though, what keeps Martha engaging is watching Cutler thrust and parry with his subject. The prolific documentarian has done films on the likes of Anna Wintour and Dick Cheney, so he knows from prickly stars, and in Martha Stewart he has a heroine with enough power and well-earned don’t-give-a-f**k that she’ll only say exactly what she wants to say in the context that she wants to say it. Icy when she wants to be, selectively candid when it suits her purposes, Stewart makes Martha into almost a collaboration: half the story she wants to tell and half the degree to which Cutler buys that story. And the latter, much more than the completely bland biographical trappings and rote formal approach, is entertaining.

Cutler has pushed the spotlight exclusively onto Stewart. Although he’s conducted many new interviews for the documentary, with friends and co-workers and family and even a few adversaries, only Stewart gets the on-screen talking head treatment. Everybody else gets to give their feedback in audio-only conversations that have to take their place behind footage of Martha through the years, as well as the current access Stewart gave production to what seems to have been mostly her lavish Turkey Hill farmhouse.

Those “access” scenes, in which Stewart goes about her business without acknowledging the camera, illustrate her general approach to the documentary, which I could sum up as “I’m prepared to give you my time, but mostly as it’s convenient to me.”

At 83 and still busier than almost any human on the globe, Stewart needs this documentary less than the documentary needs her, and she absolutely knows it. Cutler tries to draw her out and includes himself pushing Stewart on certain points, like the difference between her husband’s affair, which still angers her, and her own contemporaneous infidelity. Whenever possible, Stewart tries to absent herself from being an active part of the stickier conversations by handing off correspondences and her diary from prison, letting Cutler do what he wants with those semi-revealing documents.

“Take it out of the letters,” she instructs him after the dead-ended chat about the end of her marriage, adding that she simply doesn’t revel in self-pity.

And Cutler tries, getting a voiceover actor to read those letters and diary entries and filling in visual gaps with unremarkable still illustrations.

Just as Stewart makes Cutler fill in certain gaps, the director makes viewers read between the lines frequently. In the back-and-forth about their affairs, he mentions speaking with Andy, her ex, but Andy is never heard in the documentary. Take it as you will. And take it as you will that she blames prducer Mark Burnett for not understanding her brand in her post-prison daytime show — which may or may not explain Burnett’s absence, as well as the decision to treat The Martha Stewart Show as a fleeting disaster (it actually ran 1,162 episodes over seven seasons) and to pretend that The Apprentice: Martha Stewart never existed. The gaps and exclusions are particularly visible in the post-prison part of her life, which can be summed up as, “Everything was bad and then she roasted Justin Bieber and everything was good.”

Occasionally, Stewart gives the impression that she’s let her protective veneer slip, like when she says of the New York Post reporter covering her trial: “She’s dead now, thank goodness. Nobody has to put up with that crap that she was writing.” But that’s not letting anything slip. It’s pure and calculated and utterly cutthroat. More frequently when Stewart wants to show contempt, she rolls her eyes or stares in Cutler’s direction waiting for him to move on. That’s evisceration enough.

Stewart isn’t a producer on Martha, and I’m sure there are things here she probably would have preferred not to bother with again at all. But at the same time, you can sense that either she’s steering the theme of the documentary or she’s giving Cutler what he needs for his own clear theme. Throughout the first half, her desire for perfection is mentioned over and over again and, by the end, she pauses and summarizes her life’s course with, “I think imperfection is something that you can deal with.”

Seeing her interact with Cutler and with her staff, there’s no indication that she has set aside her exacting standards. Instead, she’s found a calculatedly imperfect version of herself that people like, and she’s perfected that. It is, as she might put it, a good thing.

Movie Reviews

Reagan Is Almost Fun-Bad But It’s Mostly Just Bad-Bad

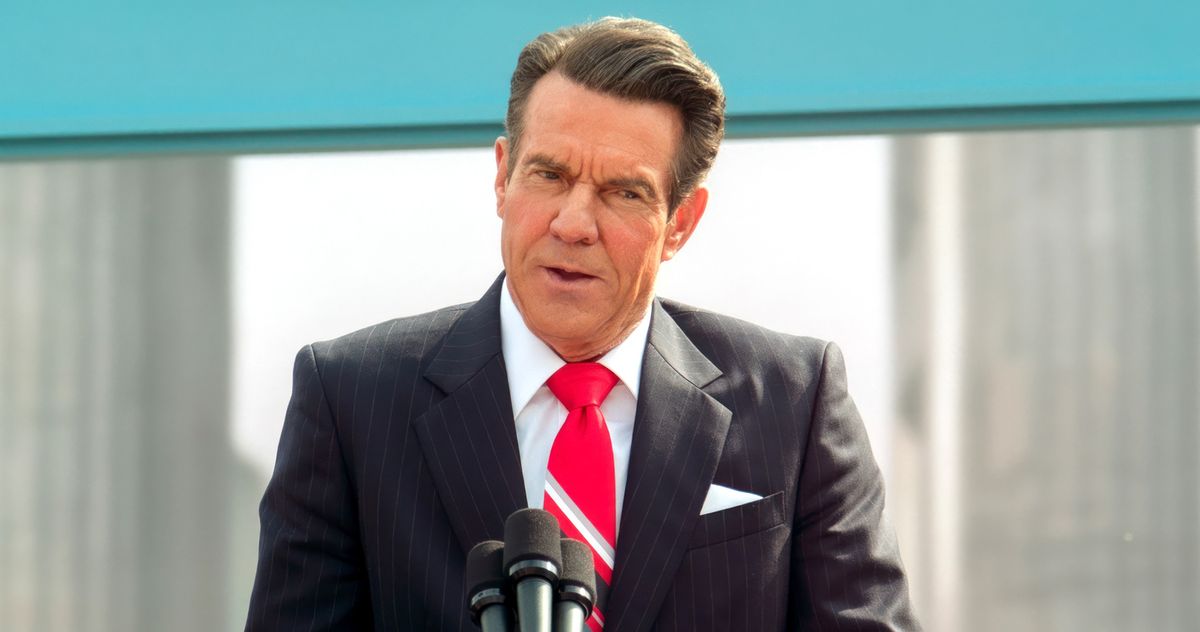

Dennis Quaid in Reagan.

Photo: Showbiz Direct/Everett Collection

Reagan is pure hagiography, but it’s not even one of those convincing hagiographies that pummel you into submission with compelling scenes that reinforce their subject’s greatness. Sean McNamara’s film has slick surfaces, but it’s so shallow and one-note that it actually does Ronald Reagan a disservice. The picture attempts to take in the full arc of the President’s life, following him from childhood right through to his 1994 announcement at the age of 83 that he’d been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s Disease. But you’d never guess that this man was at all complex, complicated, conflicted — in other words, human. He might as well be one of those animatronic robots at Disney World, mouthing lines from his famous speeches.

Dennis Quaid, a very good actor who can usually work hints of sadness into his manic machismo, is hamstrung here by the need to impersonate. He gets the voice down well (and he certainly says “Well” a lot) and he tries to do what he can with Reagan’s occasional political or career setbacks, but gone is that unpredictable glint in the actor’s eye. This Reagan doesn’t seem to have much of an interior life. Everything he thinks or feels, he says — which is maybe an admirable trait in a politician, but makes for boring art.

The film’s arc is wide and its focus is narrow. Reagan is mainly about its subject’s lifelong opposition to Communism, carrying him through his battles against labor organizers as president of the Screen Actors Guild and eventually to higher public office. The movie is narrated by a retired Soviet intelligence official (Jon Voight) in the present day, answering a younger counterpart’s questions about how the Russian empire was destroyed. He calls Reagan “the Crusader” and the moniker is meant to be both combative and respectful: He admires Reagan’s single-minded dedication to fighting the Soviets. They, after all, were single-minded in their dedication to fighting the U.S., and the agent has a ton of folders and films proving that the KGB had been watching Reagan for a long, long time.

By the way, you did read that correctly. Jon Voight plays a KGB officer in this picture, complete with a super-thick Russian accent. There’s a lot of dress-up going on — it’s like Basquiat for Republicans, even though the cast is certainly not all Republicans — and there’s some campy fun to be had here. Much has been made of Creed’s Scott Stapp doing a very flamboyant Frank Sinatra, though I regret to announce that he’s only onscreen for a few seconds. Robert Davi gets more screentime as Leonid Brezhnev, as does Kevin Dillon as Jack Warner. Xander Berkeley puts in fine work as George Schultz, and a game Mena Suvari shows up as an intriguingly pissy Jane Wyman, Reagan’s first wife. As Margaret Thatcher, Lesley-Anne Down gets to utter an orgasmic “Well done, cowboy!” when she sees Reagan’s “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall” speech on TV. And my ’80s-kid brain is still processing C. Thomas Howell being cast as Caspar Weinberger.

To be fair, a lot of historians give Reagan credit for helping bring about both the Gorbachev revolution and the eventual downfall of the U.S.S.R. and its satellites, so the film’s focus is not in and of itself a misguided one. There are stories to be told within that scope — interesting ones, controversial ones, the kind that could get audiences talking and arguing, and even ones that could help breathe life into the moribund state of conservative filmmaking. But without any lifelike characters, it’s hard to find oneself caring, and thus, Reagan’s dedication to such narrow themes proves limiting. We get little mention of his family life (aside from his non-stop devotion to Nancy, played by Penelope Ann Miller, and vice versa). Other issues of the day are breezed through with a couple of quick montages. All of this could have given some texture to the story and lent dimensionality to such an enormously consequential figure. But then again, if the only character flaw you could find in Ronald Reagan was that he was too honest, then maybe you weren’t very serious about depicting him as a human being to begin with.

See All

Movie Reviews

‘Don’t Let’s Go to the Dogs Tonight’ Review: An Extraordinary Adaptation Takes a Child’s-Eye View of an African Civil War

Alexandra Fuller‘s bestselling 2001 memoir of growing up in Africa is so cinematic, full of personal drama and political upheaval against a vivid landscape, that it’s a wonder it hasn’t been turned into a film before. But it was worth waiting for Embeth Davidtz’s eloquent adaptation, which depicts a child’s-eye view of the civil war that created the country of Zimbabwe, formerly Rhodesia — a change the girl’s white colonial parents fiercely resisted.

Davidtz, known as an actress (Schindler’s List, among many others), directs and wrote the screenplay for Don’t Let’s Go to the Dogs Tonight and stars as Fuller’s sad, alcoholic mother. Or, actually, co-stars, because the entire movie rests on the tiny shoulders and remarkably lifelike performance of Lexi Venter — just 7 when the picture, her first, was shot. It is a bold risk to put so much weight on a child’s work, but like so many of Davidtz’s choices here, it also turns out to be shrewd.

Don’t Let’s Go to the Dogs Tonight

The Bottom Line Near perfection.

Venue: Telluride Film Festival

Cast: Lexi Venter, Embeth Davidtz, Zikhona Bali, Fumani N Shilubana, Rob Van Vuuren, Anina Hope Reed

Director-screenwriter: Embeth Davidtz

1 hour 38 minutes

Another those smart calls is to focus intensely on one period of Fuller’s childhood. Don’t Let’s Go to the Dogs Tonight is set in 1980, just before and during the election that would bring the country’s Black majority to power. Bobo, as Fuller was called, is a raggedy kid with a perpetually dirty face and uncombed hair, who’s seen at times riding a motorbike or sneaking cigarettes. She runs around the family farm, whose run-down look and dusty ground tell of a hardscrabble existence. The film was shot in South Africa, and Willie Nel’s cinematography, with glaring bright light, suggests the scorching feel of the sun.

Much of the story is told in Bobo’s voiceover, in Venter’s completely natural delivery, and in another daring and effective choice, all of it is told from her point of view. Davidtz’s screenplay deftly lets us hear and see the racism that surrounds the child, and the ideas that she has innocently taken in from her parents. And we recognize the emotional cost of the war, even when Bobo doesn’t. She often mentions terrorists, saying she is afraid to go into the bathroom alone at night in case there’s one waiting for her “with a knife or a gun or a spear.” She keeps an eye out for them while riding into town in the family car with an armed convoy. “Africans turned into terrorists and that’s how the war started,” she explains, parroting what she has heard.

At one point, the convoy glides past an affluent white neighborhood. That glimpse helps Davidtz situate the Fullers, putting their assumptions of privilege into context. Bobo has absorbed those notions without quite losing her innocence. Referring to the family’s servants, her voiceover says that Sarah (Zikhona Bali) and Jacob (Fumani N. Shilubana) live on the farm, and that “Africans don’t have last names.” Bobo adores Sarah and the stories she tells from her own culture, but Bobo also feels that she can boss Sarah around.

Venter is astonishing throughout. In close-up, she looks wide-eyed and aghast when visiting her grandfather, who has apparently had a stroke. At another point, she says of her mother, “Mum says she’d trade all of us for a horse and her dogs.” When she says, after the briefest pause, “But I know that’s not true,” her tone is not one of defiant disbelief or childlike belief, as might have been expected. It’s more nuanced, with a hint of sadness that suggests a realization just beyond her young grasp. Davidtz surely had a lot to do with that, and her editor, Nicholas Contaras, has cut all Bobo’s scenes into a sharply perfect length. Nonetheless, Venter’s work here brings to mind Anna Paquin, who won an Oscar as a child for her thoroughly believable role as a girl also who sees more than she knows in The Piano.

The largely South African cast displays the same naturalism as Venter, creating a consistent tone. Rob Van Vuuren plays Bobo’s father, who is at times away fighting, and Anina Hope Reed is her older sister. Bali and Shilubana are especially impressive as Sarah and Jacob, their portrayals suggesting a resistance to white rule that the characters can’t always speak out loud.

Davidtz has a showier role as Nicola Fuller. (The movie doesn’t explain its title, which hails from the early 20th century writer A.P Herbert’s line, “Don’t let’s go the dogs tonight, for mother will be there.”) Once, Nicola shoots a snake in the kitchen and calmly wanders off, ordering Jacob to bring her tea. More often, Bobo watches her mother drift around the house or sit on the porch in an alcoholic fog. But when her voiceover tells us about the little sister who drowned, we fathom the grief behind Nicola’s depression. And wrong-headed though she is, we understand her fury and distress when the election results make her feel that she is about to lose the country she thinks of as home. Davidtz gives herself a scene at a neighborhood dance that goes on a bit too long, but it’s the rare sequence that does.

There is more of Fuller’s memoir that might be a source for other adaptations. It is hard to imagine any would be more beautifully realized than this.

-

Connecticut1 week ago

Connecticut1 week agoOxford church provides sanctuary during Sunday's damaging storm

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoBreakthrough robo-glove gives you superhuman grip

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week ago2024 showdown: What happens next in the Kamala Harris-Donald Trump face-off

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoWho Are Kamala Harris’s 1.5 Million New Donors?

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoTrump taunted over speculated RFK Jr endorsement: 'Weird as hell'

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoVivek Ramaswamy sounds off on potential RFK Jr. role in a Trump administration

-

World6 days ago

World6 days agoPortugal coast hit by 5.3 magnitude earthquake

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoHouse GOP demands elite universities counteract 'dangerous' anti-Israel protests in the fall semester