Business

Inflation improves slightly in April, but high cost of housing remains a big obstacle

Government data released Wednesday show that inflation eased a bit in April, but remains at a relatively high level. The latest report isn’t likely to lift the grim mood that much of the public has toward an otherwise solid economy.

Though incomes have generally risen more than consumer prices, the overall rate of inflation remains stubbornly high. It dropped a notch in April but was up 3.4% from a year ago, the Bureau of Labor Statistics said.

And unexpectedly, the biggest culprit is housing.

The Federal Reserve’s textbook-perfect policy of fighting inflation by pushing up interest rates has worked in large parts of the economy. The higher interest rates have helped slow growth in consumer prices for items such as food, gas, clothes and cars. Today, the inflation rate for those products is back down to, or even below, the central bank’s 2% target.

But the Fed’s same policy has paralyzed housing, an important segment of the economy, and sabotaged efforts to bring down overall inflation faster.

What the higher interest rates have done is freeze both homeowners and renters in place, discouraging either group from moving. The effect has been strong in California, where housing — what economists call the cost of “shelter” — was already very expensive.

And, in a complicated chain of cause and effect, the fact that both homeowners and renters are staying put has worked to keep inflation high.

“For two years we’ve been waiting for shelter inflation to drop enough to have an effect on the overall inflation rate. It’s constantly disappointing,” said G.U. Krueger, a longtime housing economist in Los Angeles.

“Because of high interest rates,” he said, “there’s no mobility out of rental situations to buy homes. Everyone is stuck — homeowners with golden handcuffs, renters basically with unadorned handcuffs.”

For homeowners, inflation is helping make their homes more valuable. But selling isn’t an option for many because they don’t want to give up their lower mortgage rates. Today the average 30-year fixed rate is more than 7%. Higher home prices also mean they could lose whatever gains they’d made when they replaced the house they’d sold.

For renters, there isn’t even the appearance of gains: They’re frozen in place because rent prices have failed to come down even though many new rental properties have come on the market. The typical rent for apartments and houses combined last month was about $2,920 in Los Angeles, making it one of the least affordable regions in the country, according to Zillow.

With more renters forced to stay put, there’s greater demand for, and lower vacancy at, many rental properties. That’s tended to keep pressure on prices even as more supply has come on line. Builders and landlords also are pricing rents to recoup higher costs for construction and maintenance.

Last month, consumer spending for shelter accounted for about 36% of the basket of goods and services that made up the government’s consumer price index, or CPI.

Fed policymakers track a different inflation measure in which housing isn’t given as much weight in figuring overall inflation. But both tell the same story: Housing inflation is running a lot hotter than for most other consumer goods and services.

In April, consumer prices overall rose 0.3% from March, seasonally adjusted, to an annual inflation rate of 3.4% compared with 3.5% the previous month. While that’s a dramatic decline from a 40-year high of 9.1% in June 2022, the improvement has been slowed by sticky inflation in housing.

Shelter prices in April also nudged down a bit over the month, but they were up 5.5% from a year ago, compared with 2.2% for all other goods and services combined, according to data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Earlier this year, economists were expecting that a bigger decline in overall inflation would prompt the Fed to begin the first of a series of interest rate cuts this spring. But now, with prices for housing and some other services remaining high, many analysts aren’t so sure.

“I just don’t see a catalyst for any kind of rate cut right now,” said Jack Ablin, chief investment officer at Cresset, an asset management and advisory firm. “Maybe if we’re lucky we get one cut this year.”

The Fed’s benchmark interest rate, which influences borrowing rates on homes, cars and credit cards, is at a 23-year high of about 5.3%. Higher interest rates have been felt especially hard in California’s economy, given the importance of interest-sensitive sectors such as high-tech, entertainment and real estate.

One result is that job growth in the state has lagged behind; California’s latest unemployment rate, 5.3% in March, is the highest in the land. The state’s employment report for April comes out Friday.

Experts had been more optimistic about inflation falling faster after seeing signs of declining rents last year. But average rents have begun creeping higher again in recent months, thanks in part to bigger increases for rental houses.

U.S. rents for all housing rose on average 0.6% in April from March, and now stand at a whisker below $2,000 per month, according to Zillow. That’s up 31% since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

In high-priced markets such as California, steep home prices and high mortgage rates have made homeownership more elusive and soured people’s mood about the economy, with much of the blame falling on President Biden. Surveys indicate renters are among the least happy in the state and that many are considering moving out of Los Angeles.

Chris Salviati, housing economist at Apartment List, which tracks new leasing activity, said rents have come down significantly from double-digit levels but not fast enough. “It’s still moving in the right direction, but it’s a gradual decline. Certainly it’s been frustrating for folks.”

Why is housing inflation so sticky?

One factor is that most people sign yearlong leases, so there’s a lag and it takes time for changes in rents to show up. When home prices plummeted during the Great Recession, it took about 18 months for the shelter component in the CPI to moderate, said Chris Rupkey, chief economist at Fwdbonds, a financial research firm.

CPI figures on shelter also tend to understate what many consumers are experiencing. The data show that rents for primary residences in Los Angeles and Orange counties rose 4.4% in 2022, even though prices for all other goods and services combined jumped 9.3% that year. Since then, the trend has reversed: inflation for rents and shelter have been growing much faster than for all other items.

Experts say the recent upturn in rents may be due partly to apartment owners trying to recoup their higher costs, as the broader inflationary climate has meant they’re paying more for maintenance, supplies and labor.

“Landlords are trying to catch up,” said Erica Groshen, an economist affiliated with Cornell University and former commissioner of the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, which publishes the CPI reports.

Some experts say that one possible answer to housing inflation is for the Fed to cut rates. While it may seem counterintuitive for policymakers to take such action when the economy and job market are still strong, lowering interest rates could spur mobility and also make it easier for builders to start more projects and thus boost supply.

But boosting demand for home purchases could also add more juice to home prices, at least in the short term, increasing risks of creating housing bubbles.

“For the Fed,” said Rupkey, “it’s damned if you do, and damned if you don’t.”

Business

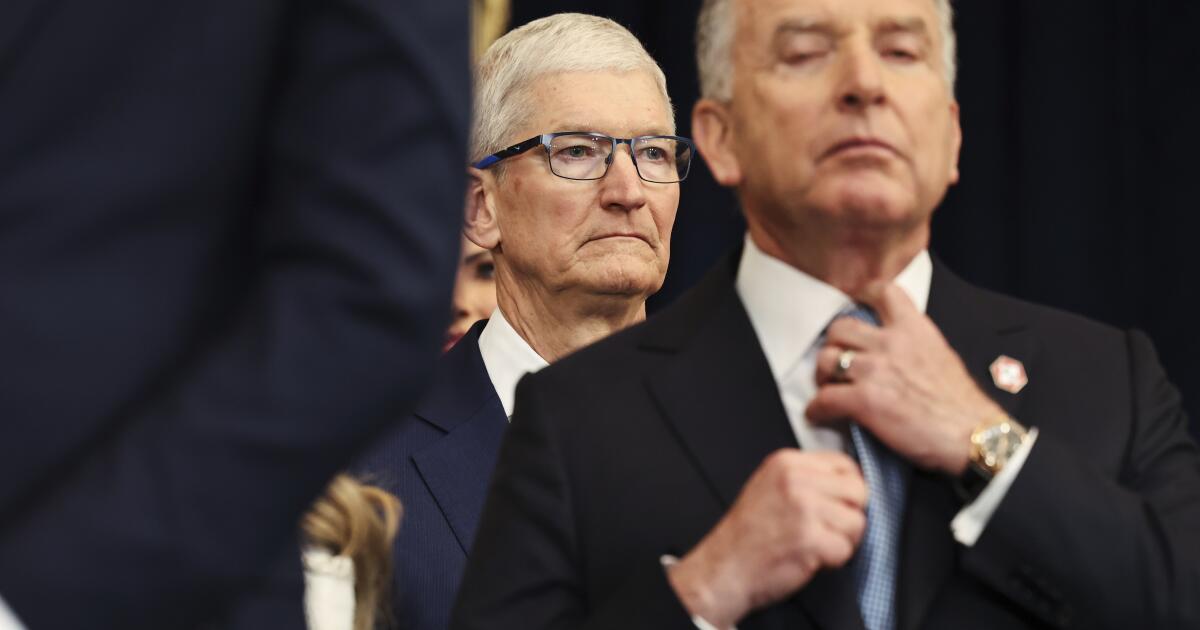

Apple is back in Trump's crosshairs over where iPhones are made

Apple Chief Executive Tim Cook can’t seem to catch a break.

Last month, Apple appeared to secure a major win when the Trump administration agreed to remove tariffs on certain electronics imported from China following concerns that the prices of smartphones and computers could rise.

But Trump threw Apple another curveball this week when he expressed frustration about the tech giant producing the iPhone in other parts of Asia.

“I have long ago informed Tim Cook of Apple that I expect their iPhone’s that will be sold in the United States of America will be manufactured and built in the United States, not India, or anyplace else. If that is not the case, a Tariff of at least 25% must be paid by Apple to the U.S.,” Trump said in a post Friday on the social network Truth Social.

Apple didn’t respond to a request for comment about Trump’s remarks.

The public spat underscores the fine line businesses are trying to walk as they try to navigate Trump’s tariffs. Tech companies in particular have to work with the new administration, while also trying to find ways to offset the costs of potential tariffs.

Trump has pushed for companies to build and manufacture products in the United States as part of an effort to strengthen national and economic security.

But shifting production to the United States would take years and result in price hikes for consumers who are already watching their spending, economists and analysts have said.

“We believe the concept of Apple producing iPhones in the U.S. is a fairy tale that is not feasible,” Wedbush Securities analyst Dan Ives said in a note Friday about Trump’s remarks.

However, Trump told reporters later Friday that he believes Apple can build an iPhone in the United States.

The tariffs are expected to start in June and would also impact Samsung and other smartphone makers “otherwise it wouldn’t be fair,” he added.

“I had an understanding with Tim that he wouldn’t be doing this. He said he’s going to India to build plants. I said, ‘That’s OK to go to India, but you’re not going to sell into here without tariffs.’ And that’s the way it is,” Trump told reporters in the Oval Office.

Apple makes most of its iPhones in China, but in recent years has expanded production in India, Vietnam and other countries.

In the June quarter, Apple expects to source the majority of iPhones sold in the United States from India, Cook said in Apple’s quarterly earnings call in May.

And Foxconn, a Taiwanese electronics contract manufacturer that assembles Apple’s products, is planning to build a $1.5-billion plant in India, the Financial Times reported, citing two anonymous government officials. A representative of Foxconn could not be reached for comment.

Ives said it would take at least five years for Apple to shift production to the U.S. and the prices of iPhones could reach $3,500 if the smartphone was made in America. Depending on the model, the current cost of an iPhone can start from $599 but go over $1,000.

Tariffs would also make it more expensive to repair an iPhone because the smartphone includes parts that come from suppliers in other countries including China, Taiwan, South Korea and Japan, according to iFixit, an ecommerce website focused on repairs. For example, the display for the iPhone 16 Pro comes from South Korea; the battery comes from China.

In total, the iPhone 16 Pro is made up of roughly 2,700 parts sourced from 187 suppliers in 28 countries, according to an April report from TechInsights.

Apple isn’t alone in navigating the potential impact of tariffs. Other U.S. companies including Walmart have said they would raise prices as they face political pressure to eat the costs of tariffs.

Apple is in a tricky spot because if the Cupertino, Calif.-based company raises the prices of iPhones, consumers could just delay buying new electronics, which would also cut into the company’s profits at a time when it is facing heavy competition from rivals in the burgeoning market for AI.

On top of that, Trump has also criticized companies such as El Segundo toy maker Mattel, which is considering raising prices, and Amazon, which considered showing the cost of tariffs next to some of its products, but didn’t approve the idea.

Cook has previously said that while there’s a popular conception that companies go to China for low labor costs, the reason Apple depends on China is for the skill of its workforce.

“In the U.S., you could have a meeting of tooling engineers and I’m not sure we could fill the room. In China, you could fill multiple football fields. It’s that vocational expertise that is very deep,” Cook said at the Fortune Global Forum in 2017.

For a time, it seemed that Apple was in Trump’s good graces. The company has garnered praise from Trump when the smartphone maker announced in February that it planned to invest $500 billion in the United States, hire 20,000 people and open a new manufacturing factory in Texas over the next four years.

Trump’s on-again, off-again tariffs have meant that businesses such as Apple are also facing economic uncertainty.

Last week, the U.S. struck a deal with Chinese officials to roll back most tariffs for 90 days. The U.S. agreed to drop the 145% tax Trump imposed on Chinese goods to 30%.

Apple has been monitoring the potential impact of tariffs. In May, Apple estimated that tariffs could add $900 million to the company’s costs, but that assumed new tariffs weren’t added.

On Friday, Apple’s stock dropped roughly 2% to $195.98 per share after Trump’s announcement.

Business

How South Korea’s next president wants to deal with Trump and his tariffs

SEOUL — The winner of South Korea’s upcoming presidential election will be faced with the task of uniting a country riven by political acrimony since the impeachment of former President Yoon Suk Yeol, who sparked national outrage after declaring martial law in December.

But first, they will have to contend with President Trump’s tariffs.

On Wednesday, U.S. and South Korean trade officials kicked off a new round of negotiations aimed at reaching a deal by July 8, when Trump’s 90-day reprieve for his “liberation day” tariffs expires. South Korea faces a 25% reciprocal tariff rate as well as product-specific duties of 25% for steel, aluminum and automobiles — all of which are major exports.

With the election scheduled for June 3, carrying these talks to the finish line will be the first and most pressing agenda item for South Korea’s next president.

For now, officials from the two countries have agreed to expand the talks beyond tariffs rates to include broader topics such as currency exchange rates and economic security — a reflection of Trump’s desire for a sweeping realignment of the U.S.–South Korea relationship that he has described as “one-stop shopping.”

But there are likely to be further complications.

Trump, who has long griped that South Korea does not pay enough for the upkeep of the 28,500 U.S. troops stationed in the country, has expressed a desire to fold defense cost-sharing into the current talks. Writing on his social media site last month, he said that he had discussed “payment for the big time Military Protection we provide to South Korea” with then-acting President Han Duck-soo.

But with Trump having once claimed he would get Seoul to pay $10 billion a year, the topic has been highly sensitive in South Korea, fueling calls for the country’s nuclear self-armament on grounds that the U.S. can no longer be relied upon for military support. There are also concerns in the country that a “package deal” favored by Trump may not work out to Seoul’s advantage.

Here’s what to know about what South Korea’s three leading presidential candidates have said about tariffs and the U.S.-South Korea relationship under Trump.

Lee Jae-myung, a candidate of the ruling Democratic Party, holds a news conference in January.

(Chung Sung-Jun / Associated Press)

Lee Jae-myung

The former leader of South Korea’s liberal Democratic Party, Lee, 61, is the front-runner in the race, having led by as many as 20 percentage points.

During Trump’s first term, Lee, then the mayor of Seongnam, cautioned against what he called “overly submissive attitudes” in the face of demands that South Korea should pay more for the presence of the U.S. military.

“Giving up whatever is demanded of us will only lead to us losing everything,” he said. “We need to boldly assert our position.”

Lee echoed those sentiments in a presidential debate Sunday, criticizing Han, the former acting president, for reportedly signaling his willingness to renegotiate the latest defense cost-sharing deal between Seoul and Washington.

Under what is known as the Special Measures Agreement, the U.S. has covered 40% to 50% of the total costs of keeping troops in South Korea, according to the U.S. Congressional Research Service.

Under the latest version, which was signed under the outgoing Biden administration and will last from 2026 to 2030, Seoul’s annual contribution in the first year will be $1.19 billion, an 8.3% increase from 2025.

A U.S. soldier walks at the Panmunjom border village in Paju, South Korea. President Trump has long complained that South Korea does not pay enough for the upkeep of the 28,500 U.S. troops stationed in the country.

(Ahn Young-joon / Associated Press)

Lee, who is running on a platform of pragmatic diplomacy, has also stressed the need to balance South Korea’s relationship with the U.S. against those with regional neighbors such as Russia or China.

“The U.S.-South Korea alliance is important, and we need to expand and develop that in the future — from a security alliance into an economic alliance and a comprehensive alliance,” he said Sunday. “But that does not mean we can rely exclusively on the U.S.-South Korea alliance.”

While describing Trump’s tariffs as the “campaign of a madman,” Lee has also indicated a willingness to discuss a package deal that spans Trump’s Alaska natural gas pipeline project, the defense cost issue and cooperation in shipbuilding.

Lee’s camp has said that if elected, he will begin his term by seeking an extension of Trump’s 90-day grace period for the tariffs.

“If we win the election we will need time to closely examine the issues at the center of the trade relationship with the U.S. as well as any progress made on the tariff negotiations and come up with alternatives,” an official from Lee’s camp told the South Korean newspaper Donga Ilbo last week.

South Korea’s People Power Party’s presidential candidate Kim Moon-soo campaigns Tuesday in Seoul.

(Ahn Young-joon / Associated Press)

Kim Moon-soo

A distant second in the polls, Kim, 73, served as labor minister under the impeached Yoon and is the conservative People Power Party’s nominee.

Staying true to the South Korean right’s self-identification as the staunchly pro-U.S. political camp, Kim has accused Lee of seeking to curry favor with China at the expense of the U.S.-South Korea relationship.

“Your comments in the past would be considered appalling from the perspective of the U.S.,” he told Lee at the debate Sunday.

Participants march to the headquarters of the People Power Party in Seoul during a December 2024 rally to demand South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol’s impeachment.

(Ahn Young-joon / Associated Press)

Unlike Lee, who has warned against rushing into a trade deal in favor of a slower and more strategic approach, Kim has said that he would immediately set up a U.S.-South Korea summit to ink a deal before July 8, if he is elected president.

“I will make sure that tariffs against South Korea are either removed or the lowest out of any country in the world,” he said at a recent rally.

To this end, Kim has cast himself as the candidate with the greatest chance of winning over Trump.

During his party’s primary debates in April, when asked by the moderator whether he would wear a MAGA hat if Trump requested it during any tariff negotiations, Kim responded: “I would do even more, I would even wear a jumper if he asked.”

“The most important thing in negotiating with President Trump is trust,” he said Sunday. “Only when both sides can trust each other can the U.S.-South Korea alliance be strengthened, and I am the one who has the most favorable and trusting relationship with President Trump.”

A currency trader works at the foreign exchange dealing room of KEB Hana Bank headquarters in Seoul last month.

(Ahn Young-joon / Associated Press)

On defense cost-sharing, Kim has struck a noticeably more acquiescent tone than Lee: At a meeting Monday of the American Chamber of Commerce in Korea, he said that he would be willing to accept a hike in Seoul’s contribution.

“The global order and trade environment is rapidly changing. In order to overcome these crises, it is critical that we strengthen positive cooperation and the U.S.-South Korea alliance,” he said. “I will establish common ground between the two countries through comprehensive negotiations and find a win-win solution for both.”

Lee Jun-seok, the presidential candidate of the New Reform Party, center, runs to attend a campaign event Saturday in Seoul.

(Ahn Young-joon / Associated Press)

Lee Jun-seok

Polling around 10%, the 40-year old candidate from the conservative Reform Party faces long odds for the presidency.

Still, he has emphatically rejected repeated calls to form a unity ticket, presenting himself as the younger, shrewder and less doctrine-driven alternative to what he has criticized as the old-hat conservatism of those such as Kim.

At the debate Sunday, Lee Jun-seok called for “careful calculation” in navigating the U.S.-South Korea relationship under Trump, while emphasizing the need to demonstrate that South Korea is not just a trading partner but also an important strategic ally to Washington.

Yet when it comes to tariffs, he has also openly called Trump’s bluff.

“I think we have to bet on the fact that Trump will eventually find that it’s difficult to maintain this situation,” he said on a YouTube political talk show last month, citing the economic pressures that tariffs against China will create for Trump’s heartland supporters.

“What Trump is advancing isn’t sustainable…. My view is that, it’s likely that Trump will admit defeat as soon as within the next six months.”

Business

CalRecycle drafts revised plastic recycling rules that are more friendly to industry

State waste officials have taken another stab at rules implementing a landmark plastic waste law, more than two months after Gov. Gavin Newsom torpedoed their initial proposal.

CalRecycle, the state agency that oversees waste management, recently proposed a new set of draft regulations to implement SB 54, the 2022 law designed to reduce California’s single-use plastic waste. The law was designed to shift the financial onus of waste reduction from the state’s people, towns and cities to the companies and corporations that make the polluting products. It was also intended to reduce the amount of single-use plastics that end up in California’s waste stream.

The draft regulations proposed last week largely mirror the ones introduced earlier this year, which set the rules, guidelines and parameters of the program — but with some minor and major tweaks.

The new ones clarify producer obligations and reporting timelines, said organizations representing packaging and plastics companies, such as the Circular Action Alliance and the California Chamber of Commerce.

But they also include a broad set of exemptions for a wide variety of single-use plastics — including any product that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and the U.S. Department of Agriculture have jurisdiction over, which includes all packaging related to produce, meat, dairy products, dog food, toothpaste, condoms, shampoo and cereal boxes, among other products.

The rules also leave open the possibility of using chemical or alternative recycling as a method for dealing with plastics that can’t be recycled via mechanical means, said people representing environmental, recycling and waste hauling companies and organizations.

California’s attorney general, Rob Bonta, filed a suit against ExxonMobil last year that, in part, accuses the oil giant of deceptive claims regarding chemical recycling, which the company disputes.

Critics say the introduction of these exemptions and the opening for polluting recycling technologies will undermine and kneecap a law that just three years ago Newsom’s office described as “nation-leading” and “the most significant overhaul of the state’s plastic and packaging policy in history.”

The “gaping hole that the new exemptions have blown” into the bill make it unworkable, practically unfundable, and antithetical to its original purpose of reducing plastic waste, said Heidi Sanborn, director of the National Stewardship Action Council.

Last March, after nearly three years of negotiations among various corporate, environmental, waste, recycling and health stakeholders, CalRecycle drafted a set of finalized regulations designed to implement the single-use plastic producer responsibility program under SB 54.

But as the deadline for implementation approached, industries that would be affected by the regulations including plastic producers and packaging companies — represented by the California Chamber of Commerce and the Circular Action Alliance — began lobbying the governor, complaining the regulations were poorly developed and might ultimately increase costs for California taxpayers.

Newsom allowed the regulations to expire and told CalRecycle it needed to start the process over.

Daniel Villaseñor, a spokesman for the governor, said Newsom was concerned about the program’s potential costs for small businesses and families, which a state analysis estimated could run an extra $300 per year per household.

He said the new draft regulations “are a step in the right direction” and they ensure “California’s bold recycling law can achieve its goal of cutting plastic pollution,” said Villaseñor in a statement.

John Myers, a spokesman for the California Chamber of Commerce, whose members include the American Chemistry Council, Western Plastics Assn. and the Flexible Packaging Assn., said the chamber was still reviewing the changes.

CalRecycle is holding a workshop next Tuesday to discuss the draft regulations. Once CalRecycle decides to finalize the regulations, which experts say could happen at any time, it moves into a 45-day official rule-making period during which the regulations are reviewed by the Office of Administrative Law. If it’s considered legally sound and the governor is happy, it becomes official.

The law, which was authored by state Sen. Ben Allen (D-Santa Monica) and signed by Newsom in 2022, requires that by 2032, 100% of single-use packaging and plastic foodware produced or sold in the state must be recyclable or compostable, that 65% of it can be recycled, and that the total volume is reduced by 25%.

The law was written to address the mounting issue of plastic pollution in the environment and the growing number of studies showing the ubiquity of microplastic pollution in the human body — such as in the brain, blood, heart tissue, testicles, lungs and various other organs.

According to one state analysis, 2.9 million tons of single-use plastic and 171.4 billion single-use plastic components were sold, offered for sale or distributed during 2023 in California.

Most of these single-use plastic packaging products cannot be recycled, and as they break down in the environment — never fully decomposing — they contribute to the growing burden of microplastics in the air we breathe, the water we drink, and the soil that nourishes our crops.

The law falls into a category of extended producer responsibility laws that now regulate the handling of paint, carpeting, batteries and textiles in California — requiring producers to see their products throughout their entire life cycle, taking financial responsibility for their products’ end of life.

Theoretically such programs, which have been adopted in other states, including Washington, Oregon and Colorado, spur technological innovation and potentially create circular economies — where products are designed to be reused, recycled or composted.

Sanborn said the new exemptions not only potentially turn the law “into a joke,” but will also dry up the program’s funding and instead put the financial burden on the consumer and the few packaging and single-use plastic manufacturers that aren’t included in the exemptions.

“If you want to bring the cost down, you’ve got to have a fair and level playing field where all the businesses are paying in and running the program. The more exemptions you give, the less funding there is, and the less fair it is,” she said.

In addition, because of the way residential and commercial packaging waste is collected, “it’s all going to get thrown away together, so now you have less funding” to deal with the same amount of waste, but for which only a small number of companies will be accountable for sorting out their material and making sure it gets disposed of properly.

Others were equally miffed, including Allen, the bill’s author, who said in a statement that while there are some improvements in the new regulations, there are “several provisions that appear to conflict with law,” including the widespread exemptions and the allowance of polluting recycling technologies.

“If the purpose of the law is to reduce single-use plastic and plastic pollution,” said Anja Brandon from the Ocean Conservancy, these new regulations aren’t going to do it — they are “inconsistent with the law and fully undermine its purpose and goal.”

Nick Lapis with Californians Against Waste said his organization was “really disappointed to see the administration caving to industry on some core parts of this program,” and also noted his read suggests many of the changes don’t comply with the law.

Next Tuesday, the public will have an opportunity to express concerns at a rulemaking workshop in Sacramento.

However, Sanborn fears there will be little time or appetite from the agency or the governor’s office to make substantial changes to the new regulations.

“They’re basically already cooked,” said Sanborn, noting CalRecycle had already accepted public comments during previous rounds and iterations.

“California should be the leader at holding the bar up in this space,” she said. “I’m afraid this has dropped the bar very low.”

-

Education1 week ago

Education1 week agoVideo: Opinion | We Study Fascism, and We’re Leaving the U.S.

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoLove, Death, and Robots keeps a good thing going in volume 4

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoAs Harvard Battles Trump, Its President Will Take a 25% Pay Cut

-

Culture1 week ago

Culture1 week agoBook Review: ‘Hunger Like a Thirst,’ by Besha Rodell

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoMeta asks judge to throw out antitrust case mid-trial

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoRepublicans say they're 'out of the loop' on Trump's $400M Qatari plane deal

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoCommissioner Hansen presents plan to cut farming bureaucracy in EU

-

Movie Reviews1 week ago

Movie Reviews1 week agoClassic Film Review: ‘Mad Max: Fury Road’ is a Lesson in Redemption | InSession Film